Abstract

This paper estimates the effects of motherhood timing on female career path, using biological fertility shocks to instrument for age at first birth. Motherhood delay leads to a substantial increase in earnings of 9% per year of delay, an increase in wages of 3%, and an increase in work hours of 6%. Supporting a human capital story, the advantage is largest for college-educated women and those in professional and managerial occupations. Panel estimation reveals both fixed wage penalties and lower returns to experience for mothers, suggesting that a “mommy track” is the source of the timing effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

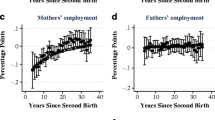

Figures A1 to A5 in the electronic supplemental materials of this paper depict the relationships in age–earnings, age–hours, and age–wage profiles for women grouped by A1B. Mothers with A1B in the 30 to 34 range outperform the two groups of earlier mothers (A1B 20 to 24 and A1B 25 to 30) by the age of 35. Although more pronounced at age 35, the differences in wage rates and wage growth rates are apparent even prior to childbearing. Later mothers appear to have higher ability than earlier mothers, and earn even higher wages than childless women.

Hewlett (2002) describes some personal costs of motherhood delay and argues that many women with successful careers have come to regret the family sacrifices they made to further their professional goals.

Section 6 of this paper employs a more flexible specification of the panel estimation strategy, including fixed effects in both wage levels and their growth rates, and using instrumental variables constructed from biological fertility shocks.

Further evidence supporting the validity of the instruments is presented in Sections 3, 4, and 5. These instrumental variables are used in Miller (2009) to estimate the impact of motherhood delay on children’s test scores. Similar variation in fecundity is exploited in Cristia (2008), who finds substantial labor supply effects from motherhood on a sub-sample of women in the National Survey of Family Growth who sought fertility assistance.

This may be caused by women who expect larger depreciation costs choosing to delay motherhood.

The wage effects found in the panel estimates in Section 6 have been confirmed in later papers such as Ellwood et al. (2004) and Loughran and Zissimopoulos (2009) using OLS models. Both papers extend the analysis to consider career outcomes for men and Loughran and Zissimopoulos (2009) also estimates the effects of marriage timing.

It does depend on the assumptions of no discounting and that the duration of the break is independent of the timing of motherhood. If women work part-time after childbearing, the exact equivalence only holds in the case of linear returns to experience.

For an anecdotal account from the legal profession, see Mumford’s experience of motherhood as an associate at a major New York City law firm in Chen (2003).

This may be especially relevant for women working in academia (Mason and Goulden 2002), law, medicine, and accounting.

In this case, the thought experiment must be altered to allow for the duration of the break to vary with motherhood timing, as a result of some optimization that depends on age at first birth. The “total effect of delay” is defined to include the effect of increased labor supply.

This would happen, for example, if women who are more successful and energetic in their careers are also more “successful and energetic” in their personal lives, marrying and bearing children sooner.

One way to address the concern of declining fecundity is to estimate the effect of delay separately women who had their first child within different age ranges. Due to the small sample size, this exercise does not produce precise estimation results.

Regan (2001) describes miscarriage risks associated with heavy alcohol use, drug use (cocaine, marijuana, and cannabinoid compounds), and regular smoking during pregnancy.

Negative bias would occur if women who are better organized at work are able to conceive more quickly, or if women with higher unobserved productivity choose to target their A1B timing more precisely and use contraception until they desire motherhood.

Confidential Geocode data are used for state level identification of family leave regime. Additional testing using data through 2006 confirms the main findings for career outcomes between ages 21 and 40. Unfortunately, attrition from the survey after 2000 substantially reduces the sample size for the analysis using later years of data.

The military and the economically disadvantaged samples were survey until 1983 and 1988, respectively.

For example, if the IV regression on total earnings from Table 2 is repeated on the expanded sample, the A1B coefficient is 0.088 with a standard error of 0.024. The IV estimate for average wages is 0.031 (s.e. of 0.012) and for total hours of experience is 0.038 (s.e. of 0.015).

For the main cross-sectional sample of career outcomes, earnings between ages 21 and 34 are known for 3,043 women. Of those, 492 were childless by 2000 and 135 had missing fertility information. The age at first birth restrictions eliminate another 719 women with teenage pregnancy leading to first birth and 126 women with first birth after age 33. The year at first birth restriction drops another 226 women. Missing values for the instrumental variables and substance abuse controls are responsible for the remaining sample loss and variation. The cross-sectional sample for terminal wages rates and the panel sample of wages and wage growth are restricted to working women who report wages at the relevant ages.

Results are unchanged if wages in missing years (1994, 1996, and 1998) are omitted or if the sample is limited to women aged 18 and older in 1979. The estimated effect of A1B on career earnings are 10% and 12% respectively, each statistically significant at 1%.

This is equivalent to a weighted average, by hours worked at that rate, of all wage rates received during the period.

NLSY79 respondents were not rewarded based on their test performance. As a result, scores most likely reflect some combination of ability and motivation, both of which matter for labor market outcomes (Segal 2006).

Ruhm (1997) outlines the provisions, coverage, and consequences of the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Waldfogel (1999) is the source for state maternity leave rules.

Hotz et al. (1997) estimates bounds on the effects of teen motherhood that incorporates potential contamination of the miscarriage natural experiment from misreporting, and from latent abortion-types who miscarry. These bounds confirm the qualitative instrumental variables findings. The problem of latent abortion types in the miscarriage group should be smaller in this paper, because the present sample is limited to women who become mothers after age 20, and abortion rates are substantially lower (less than half as high) for these later pregnancies.

This instrument may be susceptible to measurement error, especially in the date of the initial pregnancy attempt. It is reassuring to note that the main results are largely unchanged when it is removed: the effect of delay on career earnings and wages increases to 0.16 (s.e. of 0.023) and 0.07 (s.e. of 0.038), respectively, and the effect on hours decreases to 0.03 (s.e. of 0.04).

One difference in rates of accidental pregnancy and accidental live birth is abortion. Another difference between the NSFG estimate and my sample is that I exclude teenage mothers.

Results are robust to expanding the career window as far as the maximum observed age of 42 or to including additional data from later surveys and estimating career outcomes between ages 21 and 40 for women of all birth year cohorts.

This is an interesting reversal of the unconditional relationships in the data, where Black and Hispanic women report lower earnings. The main source of the change is the inclusion of the AFQT control variable, but the sample restriction (to exclude teen mothers) also plays a role.

This is confirmed in separate Probit and IV-Probit results, where A1B is found to be a positive predictor of working full time in the year, 2 years and 3 years following first birth.

Since shocks occur during the entire period, the estimate captures the average effect of a delay across women of different ages. Regressions were run using polynomial terms in A1B to consider non-linearity in the effect of delay by A1B, but coefficients were imprecisely estimated.

As a robustness exercise, the main regressions on career and terminal wage outcomes were repeated with the full set of indicators for contraceptive type. In each case, the A1B point estimate became slightly larger and remained statistically significant. Hence, the results are not being driven by differences in the type of contraception used.

Public sector jobs have been associated with smaller motherhood wage penalties in Europe (Nielsen et al. 2004). If this is true in the US as well, the impact of A1B should be smaller for government workers, which is consistent with the negative point estimate. In an unreported regression, the interaction of A1B with spouse earnings is also negative and statistically insignificant.

In another specification, state laws were ignored, and family leave was presented by an indicator for first birth occurring after the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). The coefficient on A1BbFMLA is 0.018 in OLS and 0.037 in IV.

The original instrumental variables are fixed for a given woman, and cannot be used in a panel framework with individual fixed effects. Instead, they are interacted with the time-varying exogenous variable Age to produce new instruments. The new instruments are created by combining variables that are assumed to be exogenous in the wages equation (the original instruments and age). If the initial instruments are exogenous, it follows that the new instruments are exogenous as well. The exact form of the new instruments corresponds to the form of the endogenous variables.

Results are similar when three categories are used for first birth from 21 to 24, 25 to 29, and 30 to 33.

Using 2-year and 4-year intervals yielded similar but smaller coefficients.

References

Albrecht JW, Edin PA, Sundström M, Vroman SB (1999) Career interruptions and subsequent earnings: a reexamination using Swedish data. J Hum Resour 34(2):294–311

Alonzo AA (2002) Long-term health consequences of delayed childbirth. Women’s Health Issues 12(1):37–45

Amuedo-Dorantes C, Kimmel J (2005) The motherhood wage gap in the United States: the importance of fertility delay. Rev Econ Household 3(1):17–48

Angrist JD, Evans WN (1998) Children and their parents’ labor supply: evidence from exogenous variation in family size. Am Econ Rev 88(3):450–477

Atkinson R (2003) Putting parenting first: why it’s time for universal paid leave. Policy Report, Progressive Policy Institute

Baum CL (2002) The effect of work interruptions on women’s wages. Labour 16(1):1–37

Blackburn MKL, Bloom DE, Neumark D (1993) Fertility timing, wages, and human capital. J Popul Econ 6(1):1–30

Blau FD (1998) Trends in the well-being of American women, 1970–1995. J Econ Lit 36(1):112–165

Bronars SG, Grogger J (1994) The economic consequences of unwed motherhood: using twin births as a natural experiment. Am Econ Rev 84(5):1141–1156

Browning M (1992) Children and household economic behavior. J Econ Lit 30(3):1434–1475

Budig MJ, England P (2001) The wage penalty for motherhood. Am Sociol Rev 66(2):204–225

Caucutt EM, Guner N, Knowles J (2002) Why do women wait? Matching, wage inequality, and the incentives for fertility delay. Rev Econ Dyn 5(4):815–855

Chandler TD, Kamo Y, Werbel JD (1994) Do delays in marriage and childbirth affect earnings? Soc Sci Q 75(4):839–853

Chen R, Morgan SP (1991) Recent trends in the timing of first births in the United States. Demography 28(4):513–533

Chen V (2003) Cracks in the ceiling. American Lawyer 25(6)

Cramer J (1980) Fertility and female employment: problems of causal direction. Am Sociol Rev 45(2):167–190

Cristia JP (2008) The effect of a first child on female labor supply: evidence from women seeking fertility services. J Hum Resour 43(3):487–510

Crittenden A (2002) The price of motherhood: why the most important job in the world is still the least valued. Holt, New York

Dankmeyer B (1996) Long run opportunity—costs of children according to education of the mother in the Netherlands. J Popul Econ 9(3):349–361

Ellwood D, Wilde T, Batchelder L (2004) The mommy track divides: the impact of childbearing on wages of women of different skill levels. Working Paper, Russell Sage Foundation

Fuchs V (1988) Women’s quest for economic equality. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gustafsson S (2001) Optimal age at motherhood: theoretical and empirical considerations on postponement of maternity in Europe. J Popul Econ 14(2):225–247

Hewlett SA (2002) Creating a life: professional women and the quest for children. Hyperion, New York

Hofferth SL (1984) Long-term economic consequences for women of delayed childbearing and reduced family size. Demography 21(2):141–155

Hotz VJ, Mullin CH, Sanders SG (1997) Bounding causal effects using data from a contaminated natural experiment: analysing the effects of teenage childbearing. Rev Econ Stud 64(4):575–603

Hotz VJ, McElroy SW, Sanders SG (2005) Teenage childbearing and its life cycle consequences: exploiting a natural experiment. J Hum Resour 60(3):683–715

Imbens GW, Angrist JD (1994) Identification and estimation of local average treatment effects. Econometrica 62(2):467–475

Joshi H, Paci P, Waldfogel J (1999) The wages of motherhood: better or worse? Camb J Econ 23(5):543–564

Klepinger D, Lundberg S, Plotnick R (1999) How does adolescent fertility affect the human capital and wages of young women? J Hum Resour 34(3):421–448

Korenman S, Neumark D (1992) Marriage, motherhood and wages. J Hum Resour 27(2):233–255

Light A, Ureta M (1995) Early-career work experience and gender wage differentials. J Labor Econ 13(1):121–154

Loughran DS, Zissimopoulos JM (2009) Why wait?: the effect of marriage and childbearing on the wages of men and women. J Hum Resour 44(2):326–349

Maranto G (1995) Delayed childbearing. Atl Mon 275(6):55

Mason MA, Goulden M (2002) Do babies matter? The effect of family formation on the lifelong careers of academic men and women. Acad Bull Am Assoc Univ Profr 88(6):21–27

Merck Manual of Diagnosis and Therapy (1999) Abnormalities of pregnancy, 17th edition, chapter 252. http://www.merck.com/pubs/mmanual/section18/chapter252/252a.htm/

Miller AR (2009) Motherhood delay and the human capital of the next generation. Am Econ Rev 99(2):154–58

Mincer J, Ofek H (1982) Interrupted work careers: depreciation and restoration of human capital. J Hum Resour 17(1):3–24

Mincer J, Polachek S (1974) Family investments in human capital: earnings of women. J Polit Econ 82(2):S76–S108

Nielsen HS, Simonsen M, Verner M (2004) Does the gap in family-friendly policies drive the family gap? Scand J Econ 106(4):721–744

Regan L (2001) Miscarriage: what every woman needs to know. Orion Books, London

Ruhm CJ (1997) The family and medical leave act. J Econ Perspect 11(3):175–186

Segal C (2006) Motivation, test scores, and economic success. Working Paper, Harvard Business School

Simonsen M, Skipper L (2006) The costs of motherhood: an analysis using matching estimators. J Appl Econ 21(7):919–934

Taniguchi H (1999) Work and family-the timing of childbearing and women’s wages. J Marriage Fam 61(4):1008–1020

Waldfogel J (1998) Understanding the ‘family gap’ in pay for women with children. J Econ Perspect 12(1):137–156

Waldfogel J (1999) Family leave coverage in the 1990s. Mon Labor Rev 122(10):13–21

Acknowledgements

I thank Susan Athey, B. Douglas Bernheim, John Pencavel, and Antonio Rangel for their excellent advising. I am grateful to the editor and anonymous referees of this journal, to Eli Berman, Katie Carman, Victor Fuchs, Larry Katz, Edward Lazear, Laura Lindsey, David Matsa, Carmit Segal, Marianne Simonsen, Scott Stern, Ed Vytlacil, and Geoff Warner, and to seminar participants at Arizona, Duke, McGill, Michigan State, Queens, UC-San Diego and Virginia for helpful comments. The Koret Foundation and the Stanford Institute for Research on Women and Gender provided generous financial support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Alessandro Cigno

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary Figure

(PDF 48 KB)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, A.R. The effects of motherhood timing on career path. J Popul Econ 24, 1071–1100 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0296-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0296-x