Abstract

In this paper, I empirically investigate the determinants of migration inflows into 14 OECD countries by country of origin between 1980 and 1995. I analyze the effect on migration of average income and income dispersion in destination and origin countries. I also examine the impact of geographical, cultural, and demographic factors as well as the role played by changes in destination countries’ migration policies. My analysis both delivers estimates consistent with the predictions of the international migration model and generates empirical puzzles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

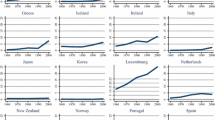

There has been a decrease in France, Japan, The Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. There has been an increase in Belgium, Canada, Germany, Luxembourg, Norway, Switzerland, and the United States (OECD 1997).

Since I began working on this paper, I have become aware of other related, but independent papers analyzing cross-country migration patterns: Alvarez-Plata et al. (2003) and Pedersen et al. (2004, 2006). I discuss these very recent contributions to the literature below, in relation to the data I use and results I find.

See also Alvarez-Plata et al. (2003) for an excellent discussion of the properties of different estimators of the determinants of migration flows.

Notice that the data set I use only covers legal migration.

Since the host countries in the sample receive a large fraction of immigrants in the world, it is not overly restrictive to focus on them. For example, according to the United Nations (2004), the list of leading host countries of international migrants in 2000—as measured by the percentage of the world’s migrant stock in each of these countries—includes the United States (20%), Germany (4.2%), France (3.6%), Canada (3.3%), Australia (2.7%), United Kingdom (2.3%), Switzerland (1%), Japan (0.9%), and The Netherlands (0.9%) (see Table ii.3, p.30). These countries all belong to my sample.

By asymmetry between pull and push factors, I mean that the coefficient on economic conditions in the source region does not have the expected sign, while the coefficient on economic conditions in the destination region is, as expected, positive and significant.

Hanson and Spilimbergo (2001) focuses on US border enforcement and shows that enforcement softens when the sectors that use illegal immigrants expand, which is evidence that migration policy is affected by changes in economic conditions in the destination country.

This interpretation goes beyond the theoretical model in this paper, which assumes exogenous migration quotas. The empirical analysis of the endogenous determination of migration policy and its role in explaining the asymmetric effect of pull and push factors is outside the scope of this paper.

This result is consistent with the findings in Hatton (2004) where emigration from Britain in the era of free migration (before 1914) is compared to emigration in 1950 onwards, when immigration policies were in place in the four main host countries of British migrants. The paper finds that, from the mid-1960s, the impact of economic and demographic forces “became less powerful as they were increasingly inhibited by immigration policies in the principal destination countries.” (p.1).

Given free trade, what explains the difference in rates of return to labor across countries? The answer is that, besides free trade, the other conditions for factor price equalization are not satisfied: for example, if international productivity differences exist, then only adjusted factor price equalization holds.

In the empirical analysis, I adjust for international differences in goods’ prices, using PPP income levels.

I assume that each individual knows the wage levels w 1i and w 0i he would get in each location, the migration costs C i and the probability η 01.

This assumption is consistent with the evidence that immigrants often arrive to a destination country with temporary tourist or student visas with the hope of being able to stay.

The reason is that, with higher \(I_{01}^D \), the range of \(\mu _1^0 \left({\mu_0} \right)\) for which the effect is strictly positive (negative) is wider (see Fig. 1).

Alvarez-Plata et al. (2003) and Pedersen et al. (2004) use different international migration datasets: the former paper uses the Eurostat Labor Force Survey which covers all destination countries within the EU-15 over 9 years; the latter paper uses a dataset constructed by the authors after contacting the statistical bureaus in 27 selected destination countries (this data set covers the years between 1990 and 2000).

Although the migration data is not perfectly comparable across OECD countries (some countries in the OECD (1997) data set define immigrants based on country of birth, while others based on citizenship), it is reasonable to think that changes over time can be compared.

Distance is calculated with the great circle formula using each capital city’s latitude and longitude data.

I linearly extrapolate data on schooling years and Gini coefficients for the years in which it is not available, based on the values for other years for the same country.

In particular, the information in the separate appendix (Mayda and Patel 2004) (and in the background papers listed in its references) was used to identify: first, the timing of immigration-policy changes taking place in each destination country (the years in which migration policy laws were passed or enforced); second, the direction of the change in the case of substantial changes (loosening vs. tightening), based on a qualitative assessment of the laws (we mainly focused on aspects of migration policies related to the size of immigration flows, as opposed to, for example, issues of citizenship).

Unfortunately, wage data cannot be used because wage income series are not available for all countries (especially origin ones) in the sample. Since per worker GDP is not a direct measure of the mean wage of the origin country’s population at home and abroad, I run robustness checks to test whether it is a good proxy for it.

In one robustness check, I control for country-pair fixed effects. In all the other regressions, I include separate destination and origin countries’ fixed effects.

Strict exogeneity of an explanatory variable implies E[X it ε is ] = 0, for ∀s, t, while predeterminacy implies E[X it ε is ] = 0, for ∀s > t. In one of the following specifications, I also control for lagged values of the emigration rate, since if the emigration rate is autocorrelated, predeterminacy of the regressors does not guarantee consistency of the estimates.

Since capital is assumed to be internationally mobile, there are no international differences in rates of return to capital.

Therefore, I do not include the regressors log distance, land border, common language, and colony since they are constant within country pairs and, therefore, would be perfectly collinear with the country-pair dummy variables.

If country pairs differ in terms of out-migration and return migration rates, net migration flows can be very different from gross flows. Since out-migration and return migration are likely to characterize specific country pairs, they are partially accounted for by including country-pair fixed effects.

I assume that ρ 01 is sufficiently high \(\left(\rho_{01} > \max \left\{ \frac{\sigma_0}{\sigma_1},\frac{\sigma_1}{\sigma_0}\right\} \right)\). The motivation for this assumption is explained in Borjas (1987): “It seems plausible to argue that for non-Communist countries, ρ 01 is likely to be positive and large. After all, profit-maximizing employers are likely to value the same factors in any market economy” (p. 534). I also assume that \(\left(\mu_{1}^{0} -\mu_{0} -\mu_{C}\right)>0\) so that, based on first-moments considerations, on average immigrants have an incentive to migrate. The motivation for the last assumption is that the dataset mostly includes migration flows from lower to higher average-income countries: the average difference in per capita GDP levels of destination and origin countries is positive and substantial (approximately $20,600). I also add a robustness check (regression 2, Table 2) where I only include observations characterized by a positive difference between the per capita GDP levels of destination and origin countries in any given year.

The Gini coefficient for Portugal was 36.76 in 1990, while in the U.S. it was 37.8. The Gini coefficient for Brazil was 61.76 in 1985, while in the U.S. it was 37.26 (Deininger and Squire 1996).

I evaluate the effect of relative inequality over the relevant range of values. Based on the coefficient estimates in column 1, Table 2, the threshold value of relative inequality is approximately equal to 2.6642: if \(\frac{\sigma _0 }{\sigma _1 }\) is below this value (which is the case almost always in my sample, based on the summary statistics in Appendix), an increase in \(\frac{\sigma _0 }{\sigma _1 }\) raises the emigration rate. This is consistent with positive selection taking place.

The multilateral pull term places migrants’ decision to move in a multicountry framework. It is inspired by the multilateral trade resistance term in Anderson and van Wincoop (2003) (even though mine is an atheoretical measure).

The Arellano and Bond estimator transforms into a difference the initial equation to remove the country-pair fixed effect and produces an equation that can be estimated with instrumental variables using a generalized method-of-moments estimator. The instruments include the lagged values of the dependent variable starting from t-4-2 (since the regression includes, as regressors, the emigration rate lagged by 1, 2, 3, and 4 years).

Regression 6 includes, as regressors, the emigration rate lagged by 1, 2, 3, and 4 years (the coefficients on the latter three lags are not shown in the table). The reason is that, only by introducing all these lags, I do not reject the null of zero autocovariance in residuals of order 2 (which is one of the requirements of the Arellano and Bond estimator).

References

Alvarez-Plata P, Brucker H, Siliverstovs B (2003) Potential migration from Central and Eastern Europe into the EU-15—an update. Report for the European Commission, DG Employment and Social Affairs

Anderson JE, van Wincoop E (2003) Gravity with gravitas: a solution to the border puzzle. Am Econ Rev 93(1):170–192

Barro R, Lee J (2000) International data on educational attainment. Data Set

Borjas GJ (1987) Self selection and the earnings of immigrants. Am Econ Rev 77(4):531–553

Borjas GJ (1999) The economic analysis of immigration. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D (eds) Handbook of labor economics, chapter 28. North-Holland Elsevier Science, The Netherlands, pp 1697–1760

Borjas GJ (2003) The labor demand curve is downward sloping: reexamining the impact of immigration on the labor market. Q J Econ 118(4):1335–1374 (Harvard University)

Borjas G, Bratsberg B (1996) Who leaves? The outmigration of the foreign-born. Rev Econ Stat 78(1):165–176

Brücker H, Siliverstovs B, Trübswetter P (2003) International migration to Germany: estimation of a time-series model and inference in panel cointegration. DIW Discussion paper No 391

Clark X, Hatton TJ, Williamson JG (2007) Explaining US immigration, 1971–1998. Rev Econ Stat 89(2):359–373

Deininger K, Squire L (1996) A new data set measuring income inequality. World Bank Econ Rev 10:565–591

Facchini G, Willmann G (2005) The political economy of international factor mobility. J Int Econ 67(1):201–219

Friedberg R, Hunt J (1995) The impact of immigrants on host country wages, employment, and growth. J Econ Perspect 9(2):23–44

Glick R, Rose A (2002) Does a currency union affect trade? The time-series evidence. Eur Econ Rev 46(6):1125–1151

Goldin C (1994) The political economy of immigration restriction in the United States, 1890 to 1921. In: Goldin C, Libecap G (eds) The regulated economy: a historical approach to political economy. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp 223–257

Hanson GH, Spilimbergo A (2001) Political economy, sectoral shocks, and border enforcement. Can J Econ 4(3):612–638

Hatton TJ (2004) Emigration from the UK, 1870–1913 and 1950–1998. Eur Rev Econ Hist 8(2):149–171

Hatton TJ (2005) Explaining trends in UK immigration. J Popul Econ 18(4):719–740

Hatton TJ, Williamson JG (2003) Demographic and economic pressure on emigration out of Africa. Scand J Econ 105(3):465–482

Helliwell JF (1998) How much do national borders matter? Chapter 5. Brookings Institution Press, Washington DC, pp 79–91

Hunt J (2006) Staunching emigration from East Germany: age and the determinants of migration. J Eur Econ Assoc 4(5):1014–1037

Joppke L (1998) Why liberal states accept unwanted immigration. World Polit 50(2):266–293

Karemera D, Oguledo VI, Davis B (2000) A gravity model analysis of international migration to North America. Appl Econ 32(13):1745–1755

Lopez R, Schiff M (1998) Migration and the skill composition of the labor force: the impact of trade liberalization in LDCs. Can J Econ 31(2):318–336

Mayda AM (2006) Who is against immigration? A cross-country investigation of individual attitudes toward immigrants. Rev Econ Stat 88(3):510–530

Mayda AM, Patel K (2004) OECD countries migration policies changes. Appendix to international migration: a panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows, by Anna Maria Mayda. Available at http://www.georgetown.edu/faculty/amm223/

Mishra P (2007) Emigration and wages in source countries: evidence from Mexico. J Dev Econ 82(1):180–199

OECD (1997) International migration statistics for OECD countries. Data set

Ortega F (2005) Immigration policy and skill upgrading. J Public Econ 89(9–10):1841–1863

Pedersen PJ, Pytlikova M, Smith N (2004) Selection or network effects? Migration flows into 27 OECD countries, 1990–2000. IZA Discussion Paper 1104

Pedersen PJ, Pytlikova M, Smith N (2006) Migration into OECD countries 1990–2000. In: Parson CA, Smeeding TM (eds) Immigration and the transformation of Europe. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Rodrik D (1995) Political economy of trade policy. In: Grossman G, Rogoff K (eds) Handbook of international economics, vol 3, chapter 28. North-Holland Elsevier Science, The Netherlands, pp 1457–1494

Rodrik D (2002) Comments at the conference on “Immigration policy and the welfare state”. In: Boeri T, Hanson GH, McCormick B (eds) Immigration policy and the welfare system. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 22–23

United Nations (2004) World economic and social survey 2004. International migration. United Nations, New York

Yang PQ (1995) Post-1965 immigration to the United States. Praeger, Westport, Connecticut

Yang D (2003) Financing constraints, economic shocks, and international labor migration: understanding the departure and return of Philippine overseas workers. Dissertation chapter, Harvard University

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Alberto Alesina, Elhanan Helpman, Dani Rodrik, Klaus Zimmermann, and three anonymous referees for many insightful comments. For helpful suggestions, I am also grateful to Richard Adams, Marcos Chamon, Giovanni Facchini, Bryan Graham, Louise Grogan, Russell Hillberry, Arik Levinson, Lindsay Lowell, Rod Ludema, Lant Pritchett, Maurice Schiff, Tara Watson, Jeffrey Williamson, and participants at the International Workshop at Harvard University, at the 2003 NEUDC Conference at Yale University, at the International Trade Commission Workshop, at the World Bank International Trade Seminar, and at the IZA Annual Migration Meeting. I am grateful for the research assistance provided by Krishna Patel and Pramod Khadka. All errors remain mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Klaus F. Zimmermann

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mayda, A.M. International migration: a panel data analysis of the determinants of bilateral flows. J Popul Econ 23, 1249–1274 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0251-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-009-0251-x