Abstract

This paper presents a collective discrete-choice model for female labour supply. Preferences of females and the intra-household allocation process are both econometrically identified. The model incorporates non-participation and non-linear taxation. It is applied to Belgian micro-data and is used to evaluate two revenue-neutral versions of the 2001 Tax Reform Act. We find small positive behavioural responses to the reforms. The reforms are not unambiguously welfare-improving. Generally, the first revenue-neutral reform (the actual reform and a household lump-sum tax) is more beneficial to females in couples than the second (the actual reform and a proportional decrease of household disposable incomes).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Due to the lack of adequate data, the above model has an important weakness: it does not incorporate household production (see Apps and Rees 1996, 1997; Chiappori 1997). The simple dichotomy between market time and leisure may be a questionable assumption in modelling couples' labour supply decisions. The increasing availability of time budget studies may enhance the empirical modelling of household labour supply, taking account of household production.

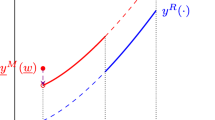

Strictly speaking, the function ϕ must give rise to a convex individual budget set. If the tax function τ c is increasing and convex in female labour supply, then this requirement is satisfied if ϕ is increasing and concave in the household's net income x (see also Donni 2003).

This variable also depends on the male's productivity. It is, for example, easily seen that, ceteris paribus, a female's earning capacity decreases if her husband's gross income increases in a joint tax system with progressive marginal rates.

Each variable that affects the bargaining power of the individuals in a household but does not affect preferences can be taken up in the sharing rule (such variables are usually called distribution factors). See Browning and Chiappori (1998) and Chiappori et al. (2002) for some examples. It may be difficult, however, to find good distribution factors. Contrary to Chiappori et al. (2002), an index capturing divorce laws or laws on alimony cannot be used for Belgium, since all regions have the same legislation on divorce and alimony.

More generally, the above approach requires that single women and females in couples have the same type of preferences (e.g. preferences that can be represented by a quadratic direct utility function). The parameters that completely define these preferences, however, may differ between both categories of women. In the estimation process, the utility function that represents preferences is normalized, such that parameters associated with individual consumption are equal.

The objective of this tax, which was introduced in 1993, was to generate extra means to meet the budget and debt criteria of the Maastricht Treaty.

This study does not make use of the “panel” structure of the data. The reason for this choice is that the SEP was subject to substantial attrition between 1992 and 1997. Many new households entered the data set in 1997, while only a very small number of households were observed in both waves of the SEP.

The sample of single males is subject to the same sample selection rules as those for single females.

Estimates are obtained by means of simulated maximum likelihood. The number of randomly drawn values for υ ℓℓi and υ ℓi equals 100.

The restrictions were tested for all four labour supply choices, taking into account the corresponding consumption levels, for each observation (both singles and women in couples). This amounts to checking the restrictions for 4×468=1,872 labour supply choices. Strictly speaking, restrictions that involve the consumption level c f (notably, the monotonicity restriction with respect to labour supply and the quasi-concavity restriction) should be satisfied for all non-negative consumption levels.

The model was also applied to the subsample of single women (to which the unitary approach should be fully applicable). Monotonicity with respect to consumption was rejected for the 38-h labour supply choice. Monotonicity with respect to labour was rejected for 25% of the labour supply choices checked. Concavity was rejected in 87% of the cases. One reason for these results might be that the model does not take into account fixed costs of work. Information on these costs, however, is lacking in the data set that we use.

Monotonicity with respect to consumption is imposed by means of the linear restriction β c =−β cℓ ·38. This implies that the collective restrictions can be imposed by the restrictions β c1 *=−β cℓ1*·38 and β c2*=−β cℓ2*·38. Note that monotonicity with respect to labour supply and quasi-concavity cannot be imposed without losing the flexibility of the behavioural model.

The male's utility level is represented by his individual consumption.

References

Apps P, Rees R (1988) Taxation and the household. J Public Econ 35:355–369

Apps P, Rees R (1996) Labour supply, household production and intra-family welfare distribution. J Public Econ 60:199–219

Apps P, Rees R (1997) Collective labour supply and household production. J Polit Econ 105:178–190

Barmby T, Smith N (2001) Household labour supply in Britain and Denmark: some interpretations using a model of Pareto optimal behaviour. Appl Econ 33:1109–1116

Bingley P, Walker I (1997) The labour supply, unemployment and participation of lone mothers in in-work transfer programs. Econ J 107:1375–1390

Blundell R, Duncan A, McCrae J, Meghir C (1999) Evaluating in-work benefit reform: the working families tax credit in the UK. Mimeo. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Blundell R, Chiappori P-A, Magnac T, Meghir C (2001) Collective labor supply: heterogeneity and nonparticipation. Mimeo. Institute for Fiscal Studies, London

Brett C (1998) Tax reform and collective family decision-making. J Public Econ 70:425–440

Browning M, Chiappori P-A (1998) Efficient intra-household allocations: a general characterization and empirical tests. Econometrica 66:1241–1278

Chiappori P-A (1988) Rational household labor supply. Econometrica 56:63–90

Chiappori P-A (1992) Collective labor supply and welfare. J Polit Econ 100:437–467

Chiappori P-A (1997) Introducing household production in collective models of labor supply. J Polit Econ 105:191–209

Chiappori P-A, Fortin B, Lacroix G (2002) Marriage market, divorce legislation and household labor supply. J Polit Econ 110:37–72

Donni O (2003) Collective household labor supply: non-participation and income taxation. J Public Econ 87:1179–1198

Fortin B, Lacroix G (1997) A test of the unitary and collective models of household labour supply. Econ J 107:933–955

Gong X, van Soest A (2002) Family structure and female labor supply in Mexico City. J Hum Resour 37:163–191

Hoynes H (1996) Welfare transfers in two-parent families: labor supply and welfare participation under AFDC-UP. Econometrica 64:295–332

Keane M, Moffitt R (1998) A structural model of multiple welfare program participation and labor supply. Int Econ Rev 39:553–589

Laisney F (ed) (2002) Welfare analysis of fiscal and social security reforms in Europe: does the representation of family decision processes matter? Final report on EU-project VS/2000/0778. Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Mannheim

Lewbel A, Chiappori P-A, Browning M (2001) Estimating consumption economies of scale, adult equivalence scales, and household bargaining power. Mimeo. Boston College, Chestnut Hill

Moreau N, Donni O (2002) Estimation d'un modèle collectif d'offre de travail avec taxation. Ann Econ Stat 65:55–84

Pencavel J (1986) Labor supply of men: a survey. In: Ashenfelter O, Layard R (eds) Handbook of labor economics, vol 1. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 3–102

Reynders D (2000) Personenbelasting. Ontwerp van fiscale hervorming (Personal income tax. Design of the fiscal reform). Ministry of Finance, Brussels

Stern N (1986) On the specification of labour supply functions. In: Blundell R, Walker I (eds) Unemployment, search and labour supply. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 143–189

Train K (1998) Recreation demand models with taste differences over people. Land Econ 74:230–239

van Soest A (1995) Structural models of family labor supply. A discrete choice approach. J Hum Resour 30:63–88

Vermeulen F (2002a) Collective household models: principles and main results. J Econ Surv 16:533–564

Vermeulen F (2002b) Where does the unitary model go wrong? Simulating tax reforms by means of unitary and collective labour supply models. The case for Belgium. In: Laisney F (ed) Welfare analysis of fiscal and social security reforms in Europe: does the representation of family decision processes matter? Final report on EU-project VS/2000/0778. Zentrum für Europäische Wirtschaftsforschung, Mannheim

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank co-editor Daniel Hamermesh, an anonymous referee, Denis Beninger, Richard Blundell, Mike Brewer, Martin Browning, Hélène Couprie, André Decoster, Xavier Joutard, François Laisney, Nicolas Moreau, Erik Schokkaert, Frans Spinnewyn and Marno Verbeek, as well as seminar participants in Antwerp, Copenhagen, Leuven, Marseille and at the EEA meeting in Stockholm for useful comments and suggestions. I am also grateful to Jeanne Bovenberg for careful editorial assistance. Earlier versions of this paper have been written when I was affiliated with the University of Leuven. Financial support of this research by the research fund of the University of Leuven (project OT 98/03) and the European Community's Human Potential Programme (contract HPRN-CT-2002-00235; AGE) is gratefully acknowledged. Of course, all errors are mine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Daniel S. Hamermesh

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vermeulen, F. A collective model for female labour supply with non-participation and taxation. J Popul Econ 19, 99–118 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0007-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00148-005-0007-1