Abstract

Introduction

The long-term outcome of “very old intensive care unit patients” (VOPs; ≥ 80 years) is often disappointing. Little is known about the healthcare costs of these VOPs in comparison to younger ICU patients and the very elderly in the general population not admitted to the ICU.

Methods

Data from a national health insurance claims database and a national quality registry for ICUs were combined. Costs of VOPs admitted to the ICU in 2013 were compared with costs of younger ICU patients (two groups, respectively 18–65 and 65–80 years old) and a matched control group of very elderly subjects who were not admitted to the ICU. We compared median costs and median costs per day alive in the year before ICU admission (2012), the year of ICU admission (2013) and the year after ICU admission (2014).

Results

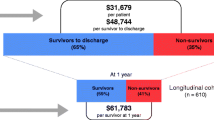

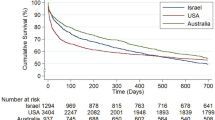

A total of 9272 VOPs were included and compared to three equally sized study groups. Median costs for VOPs in 2012, 2013 and 2014 (€5944, €35,653 and €12,565) are higher compared to the ICU 18–65 population (€3022, €30,223 and €5052, all p < 0.001) and the very elderly control population (€3590, €4238 and €4723, all p < 0.001). Compared to the ICU 65–80 population, costs of VOPs are higher in the year before and after ICU admission (€4323 and €6750, both p < 0.001), but not in the year of ICU admission (€34,448, p = 0.950). The median healthcare costs per day alive in the year before, the year of and the year after ICU admission are all higher for VOPs than for the other groups (p < 0.001).

Conclusions

VOPs required more healthcare resources in the year before, the year of and the year after ICU admission compared to younger ICU patients and the very elderly control population, except compared to the ICU 65–80 population in the year of ICU admission. Healthcare costs per day alive, however, are substantially higher for VOPs than for all other study groups in all three studied years.

Similar content being viewed by others

Availability of data and material

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available because of legal arrangements with the Vektis and NICE registry.

Abbreviations

- APACHE:

-

Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation

- APS:

-

Acute physiology score

- CAP:

-

Community-acquired pneumonia

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CVA:

-

Cerebrovascular accident

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- NICE:

-

National Intensive Care Evaluation

- OHCA:

-

Out of hospital cardiac arrest

- PCG:

-

Pharmaceutical cost group

- PICS:

-

Post-intensive care syndrome

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- SAH:

-

Subarachnoid haemorrhage

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SES:

-

Socioeconomic status

- VOSL:

-

Value of the statistical life year

- VOPs:

-

Very old intensive care patients

References

Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek (CBS). Statline. http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/dome/default.aspx. Accessed 2 Jan 2018

Halpern NA, Goldman DA, Tan KS, Pastores SM (2016) Trends in critical care beds and use among population groups and Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries in the United States: 2000–2010. Crit Care Med 44:1490–1499. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001722

Rhodes A, Ferdinande P, Flaatten H et al (2012) The variability of critical care bed numbers in Europe. Intensive Care Med 38:1647–1653. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2627-8

https://www.zorgcijfersdatabank.nl. Accessed 2 Jan 2018

Lone NI, Seretny M, Wild SH et al (2013) Surviving intensive care: a systematic review of healthcare resource use after hospital discharge. Crit Care Med 41:1832–1843. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a409c

Bagshaw SM, Webb SA, Delaney A et al (2009) Very old patients admitted to intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a multi-centre cohort analysis. Crit Care 13:R45. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc7768

Nielsson MS, Christiansen CF, Johansen MB et al (2014) Mortality in elderly ICU patients: a cohort study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 58:19–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12211

Haas LEM, Karakus A, Holman R et al (2015) Trends in hospital and intensive care admissions in the Netherlands attributable to the very elderly in an ageing population. Crit Care 19:353. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-015-1061-z

Flaatten H, de Lange DW, Artigas A et al (2017) The status of intensive care medicine research and a future agenda for very old patients in the ICU. Intensive Care Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4718-z

Vosylius S, Sipylaite J, Ivaskevicius J (2005) Determinants of outcome in elderly patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Age Ageing 34:157–162 (34/2/157)

Garrouste-Orgeas M, Timsit JF, Montuclard L et al (2006) Decision-making process, outcome, and 1-year quality of life of octogenarians referred for intensive care unit admission. Intensive Care Med 32:1045–1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-006-0169-7

Fuchs L, Chronaki CE, Park S et al (2012) ICU admission characteristics and mortality rates among elderly and very elderly patients. Intensive Care Med 38:1654–1661. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-012-2629-6

Docherty AB, Anderson NH, Walsh TS, Lone NI (2016) Equity of access to critical care among elderly patients in Scotland: a national cohort study. Crit Care Med 44:3–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001377

Flaatten H, De Lange DW, Morandi A et al (2017) The impact of frailty on ICU and 30-day mortality and the level of care in very elderly patients (≥ 80 years). Intensive Care Med 43:1820–1828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4940-8

Karakus A, Haas LEM, Brinkman S et al (2017) Trends in short-term and 1-year mortality in very elderly intensive care patients in the Netherlands: a retrospective study from 2008 to 2014. Intensive Care Med 43:1476–1484. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-017-4879-9

Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) registry. http://www.stichting-nice.nl. Accessed 2 Jan 2018

Vektis. http://www.vektis.nl. Accessed 2 Jan 2018

van de Klundert N, Holman R, Dongelmans DA, de Keizer NF (2015) Data resource profile: the Dutch National Intensive Care Evaluation (NICE) registry of admissions to adult intensive care units. Int J Epidemiol 44:1850-h. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv291

Zimmerman JE, Kramer AA, McNair DS, Malila FM (2006) Acute physiology and chronic health evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today’s critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 34:1297–1310. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000215112.84523.F0

Knol FA. Sociaal en cultureel planbureau. Van hoog naar laag: van laag naar hoog. De sociaal-ruimtelijke ontwikkeling van wijken tussen 1971-1995. [from high to low: from low to high. The socio-spatial developments of neighbourhoods between 1971 and 1995]. 13 juli 2009. Cahier, 152. Elsevier, Den Haag. ISBN 9057491176

Roos LL, Wajda A (1991) Record linkage strategies. Part I: estimating information and evaluating approaches. Methods Inf Med 30(117–123):91020117

van Beusekom I, Bakhshi-Raiez F, de Keizer NF et al (2017) Healthcare costs of ICU survivors are higher before and after ICU admission compared to a population based control group: a descriptive study combining healthcare insurance data and data from a Dutch national quality registry. J Crit Care 44:345–351

Chelluri L, Mendelsohn AB, Belle SH et al (2003) Hospital costs in patients receiving prolonged mechanical ventilation: does age have an impact? Crit Care Med 31:1746–1751. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000063478.91096.7D

Chin-Yee N, D’Egidio G, Thavorn K et al (2017) Cost analysis of the very elderly admitted to intensive care units. Crit Care 21:109–017–1689–y. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-017-1689-y

Needham DM, Davidson J, Cohen H et al (2012) Improving long-term outcomes after discharge from intensive care unit: report from a stakeholders’ conference. Crit Care Med 40:502–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232da75

Rady MY, Johnson DJ (2004) Hospital discharge to care facility: a patient-centered outcome for the evaluation of intensive care for octogenarians. Chest 126:1583–1591

Feng Y, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Kaufman D et al (2009) Age, duration of mechanical ventilation, and outcomes of patients who are critically ill. Chest 136:759–764

Conti M, Friolet R, Eckert P, Merlani P (2011) Home return 6 months after an intensive care unit admission for elderly patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 55:387–393. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-6576.2011.02397.x

Philippart F, Vesin A, Bruel C et al (2013) The ETHICA study (part I): elderly’s thoughts about intensive care unit admission for life-sustaining treatments. Intensive Care Med 39:1565–1573. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-013-2976-y

Heyland DK, Barwich D, Pichora D et al (2013) Failure to engage hospitalized elderly patients and their families in advance care planning. JAMA Intern Med 173:778–787. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.180

Raad voor Volksgezondheid en Zorg [Council for Health and Care]. Zicht op zinnige en duurzame zorg [A view on sensible and sustainable care]. 2006, publicationnumber 06/07. ISBN-10: 90-5732-172-6

Heyland DK, Garland A, Bagshaw SM et al (2015) Recovery after critical illness in patients aged 80 years or older: a multi-center prospective observational cohort study. Intensive Care Med 41:1911–1920. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-015-4028-2

Kaarlola A, Tallgren M, Pettila V (2006) Long-term survival, quality of life, and quality-adjusted life-years among critically ill elderly patients. Crit Care Med 34:2120–2126. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.CCM.0000227656.31911.2E

Andersen FH, Flaatten H, Klepstad P et al (2015) Long-term survival and quality of life after intensive care for patients 80 years of age or older. Ann Intensive Care 5:53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-015-0053-0

Tabah A, Philippart F, Timsit JF et al (2010) Quality of life in patients aged 80 or over after ICU discharge. Crit Care 14:R2. https://doi.org/10.1186/cc8231

Baldwin MR (2015) Measuring and predicting long-term outcomes in older survivors of critical illness. Minerva Anestesiol 81:650–661

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Fabian Termorshuizen for his contribution to the analysis of the data, the interpretation of the results and the writing of the manuscript. Furthermore, we thank Vektis for kindly providing the data necessary for the present analysis and especially Michiel ten Hove for his help with the interpretation of the Vektis data. And last but not least, we would like to thank all Dutch ICUs for their efforts in collecting data for continuous quality improvement and ICU research.

Funding

We did not receive financial support in any form.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH performed the analysis and drafted the manuscript. IvB, and FR performed the statistical analysis and helped with interpreting the results and writing of the manuscript. MH contributed to drafting the manuscript. DvD, DdL and NdK contributed to the interpretation of the results and drafting the manuscript, they participated in the design and coordination of the manuscript. Each author has contributed to the writing of the manuscript and finally has read and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None of the authors have a conflict of interest to disclose and all authors have read the current “Instructions to authors” and accept the conditions therein.

Ethics

The NICE registry and Vektis are registered according to the Dutch Personal Data Protection Act. The need for ethical approval for this study was waived by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Academic Medical Center and stored under number W18_017.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Haas, L.E.M., van Beusekom, I., van Dijk, D. et al. Healthcare-related costs in very elderly intensive care patients. Intensive Care Med 44, 1896–1903 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5381-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-018-5381-8