Abstract

Purpose

A persistant shortage of available organs for transplantation has driven French medical authorities to focus on organ retrieval from patients who die following the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. This study was designed to assess the theoretical eligibility of patients who have died in French intensive care units (ICUs) after a decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining therapy to organ donation.

Methods

This was an observational multi-center study in which data were collected on all consecutive patients admitted to any of the 43 participating ICUs during the study period who qualified for a withholding/withdrawal procedure according to French law. The theoretical organ donor eligibility of the patients once deceased was determined a posteriori according to current medical criteria for graft selection, as well as according to the withholding/withdrawal measures implemented and their impact on the time of death.

Results

A total of 5,589 patients were admitted to the ICU during the study period, of whom 777 (14 %) underwent withholding/withdrawal measures. Of the 557 patients who died following a foreseeable circulatory arrest, 278 (50 %) presented a contraindication ruling out organ retrieval. Of the 279 patients who would have been eligible as organ donors regardless of measures implemented, cardiopulmonary support was withdrawn in only 154 of these patients, 70 of whom died within 120 min of the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment. Brain-injured patients accounted for 29 % of all patients who qualified for the withholding/withdrawal of treatment, and 57 % of those died within 120 min of the withdrawal/withholding of treatment.

Conclusion

A significant number of patients who died during the study period in French ICUs under withholding/withdrawal conditions would have been eligible for organ donation. Brain-injured patients were more likely to die in circumstances which would have been compatible with such practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Organ transplantation brings sustainably improved quality of life to patients with end-stage organ failure. Given the worldwide shortage of suitable organs for transplantation and the ever-increasing gap between organ demand and donor graft supply, there is a need for rethinking of the practical and ethical issues concerning organ transplantation [1–3]. French policy on organ retrieval essentially hinges on brain-dead donors, while a number of other countries have based part of their transplantation policy on donation from donors with a circulatory determination of death (CDD) [4–7]. The Maastricht classification distinguishes four categories of circulatory death: unforeseeable (uncontrolled) irreversible circulatory arrest without (category I) or with (category II) immediate cardiopulmonary resuscitation, foreseeable circulatory arrest occurring after a decision to withhold/withdraw treatment (category III, controlled) and circulatory arrest occurring after brain death (category IV) [8]. Donations after unforeseeable circulatory arrest have been legally possible in France since 2005. As the procedure is restricted to a small number of suitably equipped centers, to date few organs have been retrieved under these clinical settings. Organ retrieval according to Maastricht III does not yet fall within the French legal framework. Academic and scholarly institutions have previously expressed concerns on such a procedure, arguing that it could be viewed as a form of utilitarian end-of-life practice [9–12]. In 2013, a regulatory framework making this type of organ retrieval possible was debated in the French parliament. A dedicated steering committee drafted a protocol establishing the mandatory conditions to retrieve organs under the Maastricht III classification in France [13].

To our knowledge, recent epidemiologic data describing French withholding/withdrawal practices and questioning whether such practices would be compatible with organ retrieval are not yet available. The experiences of other countries have clearly shown that the length of time between the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy and death is a major determinant of organ donation and the quality of the organs retrieved [14]. This period may range from few minutes to several days, depending on the level of life support engaged at the time of decision-making and how the treatments are withdrawn. As clinical guidelines and rules in this area mainly focus on general principles rather than practical details, there is as yet no consensus on the best airway management during the withdrawal period (cessation/decrease of ventilation with/without removal of the endotracheal tube). However, a long withdrawal period often results in severe ischemic damage, thereby compromising organ usability for transplantation [14, 15].

We therefore designed an observational multicenter study (named “EPILAT”) to describe the epidemiological characteristics of patients who died in French intensive care units (ICUs) following a formal decision to withhold/withdraw treatment, as well as to assess the theoretical eligibility of these patients as organ donors, integrating the measures implemented and the possible impact of the duration of the withdrawal period on organ viability.

Methods

This study was performed in 43 French ICUs (15 units in university-affiliated centers, 28 in general hospitals). The institutional review board (CPP Paris Ile-de-France II) approved the protocol. The study took place during the first half of 2013, and the study period consisted of 60 or 90 consecutive days under normal operating conditions. All consecutive patients admitted to any one of the participating ICUs who underwent a withholding/withdrawal procedure in compliance with the terms of the French law of April 22, 2005 (Leonetti’s law) were prospectively enrolled in the survey [16]. The epidemiological data recorded during the ICU stay included age, gender, medical history, circumstances surrounding admission, Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) II index on ICU admission, relevant clinical and biological characteristics, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score at the time of the decision-making, reasons for limiting treatment, implemented measures and patient’s outcome (deceased or discharged alive). By convention, a SOFA organ subscore of ≥3 was considered to be organ failure.

The withdrawal/withholding of treatment consisted of therapies such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation, ventilatory support, renal replacement therapy, catecholamine infusion, urgent surgery, antimicrobial therapy, transfusions, nutrition and hydration. “Withhold” was defined as the decision not to start or increase a treatment beyond a specified threshold. “Withdraw” was defined as the decision to stop a treatment already in place. Limitations were classified as “withholding” if withholding was the single limitation and as “withdrawal” if treatments were both withheld and withdrawn. “Withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments” was defined as the withdrawal of all provided ventilatory support and/or catecholamine infusion over a short period of time (10–15 min), with or without extubation (i.e. removal of the endotracheal tube), while ensuring patient comfort.

For patients who died under withholding/withdrawal conditions, their theoretical eligibility as organ donors was determined a posteriori based on medical criteria and length of time from withholding/withdrawal to death. Individual and organ-specific (kidney, liver and lung) acceptability for donation regardless of measures implemented was retrospectively assessed by the attending physician [13]. Because hemodynamic parameters were not widely available within the withdrawal period, an interval of 2 h from treatment discontinuation to cessation of cardiac activity was considered the maximum time compatible with organ viability [14].

Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), or as the median with interquartile ranges (IQR), where appropriate. Qualitative variables are expressed as absolute values with percentages. We used univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses with death within 120 min of withdrawal/withholding as a binary outcome variable (death within vs. after 120 min) to assess associations with categorical variables. Continuous measurements were converted into binary variables, according to a cut-point value allowing a reasonable number of observations in each group. For each variable, we give adjusted odds ratios (OR) and the 95 % confidence interval (CI). All univariate indices with a p value of <0.25 were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Descriptive statistics and univariate and multivariate regressions were performed using Epi Info™ (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, GA) and the R statistical package ® (Core Team, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

During the study period, 5,589 patients were admitted to 43 ICUs. Of these, 4,457 patients (80 %) were discharged alive onto the ward, and 1,132 (20 %) died in the ICU, with 117 (10 %) registered with brain death and 1,015 (90 %) registered with a CCD.

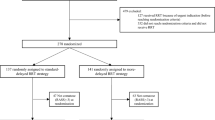

Of the 5,589 patients admitted to the ICUs, 777 (14 %) underwent withholding/withdrawal measures in 31 mixed surgical/medical (577 patients), six medical (135 patients), four surgical (41 patients) and two neurosurgical (24 patients) ICUs (Fig. 1). The reasons for admitting these 777 patients to the ICU are given in Table 1.

Flowchart of the 5,589 patients admitted to 43 intensive care units (ICUs) in terms of outcome and theoretical eligibility for organ donation. WhWd withhold or withdraw therapy, WLST withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (invasive ventilation and inotropic drugs), CDD circulatory determination of death

The rationales put forward to justify withholding/withdrawal decisions were: limited subsequent functional autonomy (581 patients), absence of curative strategy (559 patients), advanced or terminal stage of a severe and incurable disease (474 patients), limited subsequent relational quality-of-life (442 patients), older age (210 patients), perception of non-beneficial treatment voiced by patient’s relatives (172 patients) and patient’s wish to limit treatment (110 patients).

Median time from ICU admission to the decision to withhold/withdraw treatment was 4 (IQR 1–13) days. Withholding and withdrawal involved 344 and 433 patients, respectively (Table 1). For 263 patients (a subgroup of withdrawal), ongoing life-sustaining treatments (catecholamine infusion, invasive ventilation) were withdrawn with or without extubation (138 and 125 patients, respectively).

Of the 777 patients undergoing withholding/withdrawal measures, 193 (25 %) were discharged alive from the ICU, whereas 584 died (Fig. 1). Of the 584 who died, 19 were declared deceased of brain death, and eight died under limitations which did not preclude resuscitation measures in the case of cardiac arrest. These latter eight patients ultimately died despite full resuscitation efforts and, therefore, their death was considered unforeseeable. The remaining 557 patients died of foreseeable circulatory arrest without any attempt of resuscitation.

The reasons for admitting the 557 patients who ultimately died of a foreseeable cause are shown in Table 1. On the day of the withholding/withdrawal decision, 498 of these 557 patients suffered from at least one organ failure involving the neurological (327 patients), respiratory (257), circulatory (244), renal (152), hematological (60) and hepatic (42) systems, respectively. The median time from withholding/withdrawal completion to death was 2 (IQR 1–6) days after withholding (158 patients), and 1 (0–3) day after withdrawal (399 patients). The number of patients who died on day 1, 2 and 3 was 114 (26 %), 107 (24 %) and 60 (14 %) from withdrawal (433 patients), and 33 (10 %), 38 (11 %) and 14 (4 %) from withholding (344 patients), respectively.

Of the 557 patients who died of foreseeable circulatory arrest, 159 already presented a contraindication to organ donation (based on the opinion of the attending physician) either before or upon admission to the ICU (hematological or metastatic malignancies, viral hepatitis, AIDS, systemic diseases, older age). A total of 119 patients developed organ dysfunction during their ICU stay, thereby ruling out any possibility of organ retrieval (uncontrolled sepsis, multiple organ failure, shock). Therefore, 279 deceased patients would ultimately have been eligible for donation of one or more organs based on the opinion of the attending physician (regardless of withholding/withdrawal measures implemented and age). Of these 279 eligible patients, 154 underwent a withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments with (95 patients) or without extubation (59 patients). Only 70 of these 154 patients died less than 2 h after withdrawal, the timeframe considered compatible with organ viability in our study. Table 2 gives the individual and organ-specific eligibility of patients aged less than 70 and 60 years, respectively, according to the duration of the withdrawal period.

Patients with brain injury (post-cardiac arrest coma, stroke, head trauma) accounted for 32 % (179/557) of patients deceased under withholding/withdrawal conditions, 42 % (117/279) of deceased patients eligible for organ donation and 57 % (40/70) of patients deceased within 2 h after the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments who were eligible for organ donation (Table 1). Of the 70 patients deceased within a short timeframe, 21 were aged <60 years, the maximum age selected by the French steering committee for organ donation according to Maastricht III; 19 of 21 patients (90 %) had severe brain injuries on admission. With an age limit of 70 years, 37 patients would have fulfilled the conditions for organ donation, of whom 26 (70 %) suffered from brain injury on admission (Fig. 2).

Flow chart showing brain-injured patients under WhWd with regards to the outcome and theoretical eligibility for organ donation. Brain injury includes post-cardiac arrest coma, stroke and head trauma. WhWd withhold or withdraw therapy, CDD circulatory determination of death, WLST withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (invasive ventilation and inotropic drugs)

Univariate and multivariate regression analyses (Fig. 3) were used to determine factors associated with death within 120 min following withholding/withdrawal implementation in the 154 patients eligible for organ donation who were withdrawn from life-sustaining treatments before death. The single factor associated with death within 120 min was ventilation with fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) >70 % before withdrawal. In the entire group of 263 patients withdrawn from life-sustaining treatments (regardless of organ donation acceptability), ventilation with FiO2 >50 % before withdrawal (OR 2.44; 95 % CI 1.40–4.27) and extubation (OR 1.80; 95 % CI 1.07–3.01) were associated with death within 120 min.

Factors associated with death within 120 min in the 154 deceased patients eligible for organ donation who underwent WLST before death. Brain injury includes post-cardiac arrest coma, stroke and head trauma. WLST withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (invasive ventilation and inotropic drugs), OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, FiO 2 Fraction of inspired oxygen, SAPS Simplified Acute Physiology Score, SOFA Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

Discussion

To our knowledge, this study is the first assessment of potential “Maastricht III” donors performed in France prior to the launching of the program. We designed our study to obtain the largest overview of both withholding/withdrawal practices (not influenced by any other objective) and patients affected by such procedures. In this survey, 14 % of the 5,589 patients enrolled in the study underwent withholding/withdrawal measures. Among the 557 patients who died of foreseeable circulatory arrest, we identified a subgroup of 279 patients with no obvious contraindication to organ donation based on the opinion of the attending physician (regardless of withholding/withdrawal measures implemented). Life-sustaining treatments were withdrawn for 154 of these patients, 70 of whom died less than 2 h after withdrawal (the maximum delay compatible with a hypothetical organ harvesting [14]). Only 77 of the 279 eligible patients and 21 of the 70 patients deceased within 2 h from withdrawal were aged <60 years, the maximum age for a donor (according to Maastricht III) selected by the French steering committee [13]. With an age limit of 70 years, 59 additional patients would have been eligible, of whom 16 died within 2 h from withdrawal.

In our survey we made no distinction between conscious and unconscious patients under withholding/withdrawal conditions. In the UK, where the rate of organ retrieval under Maastricht III is one of the highest in the world, the most common disease affecting donors is severe and irreversible brain injury [17]. However, conscious patients suffering from irreversible severe diseases with no hope for improvement (for example end-stage respiratory disease, locked-in syndrome, atrophic lateral sclerosis) may request both withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments (i.e. turn off mechanical ventilation) and subsequent organ donation if not contraindicated [17–19]. In France, Leonetti’s law applies to both conscious and unconscious patients in an end-of-life situation or with irreversible and severely-disabling diseases [16]. As donation under Maastricht III does not yet fall with the legal framework of France, in this survey we deliberately considered every possible scenario encountered in other public healthcare systems. Albeit questionable from a pathophysiological point-of-view, we also regarded patients who recovered from shock or multiple organ failure. Finally, brain-injured patients (29 % of patients undergoing limitations) accounted for over one-half (57 %) of patients eligible as organ donors and who died within a timeframe compatible with graft viability. However, as our group only involved two units highly expert in the field of neurocritical care, we probably underestimate the proportion of brain-injured patients dying in French ICUs under withholding/withdrawal conditions.

In a previous single-center study, we reported a significant rate of patients dying under withholding/withdrawal conditions who theoretically were eligible for organ donation based on medical criteria [20]. However, the withholding/withdrawal measures implemented in this pilot unit (progressive removal of life-support devices) would have been incompatible with organ transplantation due to an extended withdrawal period. Because circulatory arrest must occur after a short period, only the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments for highly-dependent patients (high FiO2, non-triggered modes of ventilation, inotrope/vasoactive drug use) is compatible with organ donation [14, 15, 21–23]. There is a significant variability in how withholding/withdrawal are implemented in ICUs, particularly in terms of airway management [24–27]. Once the ventilator is switched off, it is possible to remove the endotracheal tube that secures the airway. Rather than remove both the ventilator and tube within a short period of time, many ICU teams prefer a progressive withdrawal of mechanical ventilation. Indeed, they believe the symptoms of airway obstruction may harm the patient and be distressing to relatives and caregivers [28]. However, other intensivists consider this progressive weaning to be an unnecessarily prolonged agony if death is the most likely outcome [29], especially as these distressing symptoms may be reliably anticipated [30]. Moreover, a formal policy on the maintenance of patient comfort throughout the entire withdrawal period is essential for the acceptance of organ donation according to Maastricht III.

Although not expressly prohibited under current French law, organ retrieval after controlled death is still not practiced “so as to rule out any potential tension between the decision to withdraw treatment and the intention to harvest organs” [9]. In other countries, teams involved in organ procurement after controlled death consider organ donation as a routine part of end-of-life care once it is established that the patient wishes to be a donor [17, 31, 32]. Our study provides an assessment of French practices, with physicians responsible for decision-making being free from any moral dilemma between the individual interest of the dying patient and the collective benefit to potential graft recipients. Of the 777 patients in our survey with limitations, 25 % left the ICU alive, thereby confirming the intention of withholding/withdrawal measures in some circumstances, which is to let nature take its course without trying to hasten death. When death is the most likely outcome, the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments usually involves the disconnection of mechanical ventilation (with or without removal of the endotracheal tube) and cessation of vasoactive drugs. The length of time to death following withdrawal is highly variable, ranging from minutes to days. However, extubation is more often associated with progression to organ donation than terminal weaning without extubation [17]. Death within 1 or 2 h of withdrawal usually correlates with severe brain injuries (low Glasgow Coma Scale, absence of brainstem reflexes) [22, 23, 33–36], high dependence on mechanical ventilation (non-triggered mode, high FiO2, high positive expiratory pressure) [15, 21–23, 34, 36, 37], use of inotrope drugs [21, 22, 33, 37], young age [15, 33, 38], underlying diseases [35, 37] and physiological anomalies (high severity index scores, low blood pressure, low pH on arterial blood gas analysis) [35, 36, 38, 39]. In our study, the factors associated with a short withdrawal period were high FiO2 and extubation.

Our study has several limitations. First, as French transplant coordinators are still not involved in organ retrieval under Maastricht III, the theoretical eligibility for organ donation was evaluated solely by the physician in charge of the patient. In some cases, patients were declared dead without any obvious contraindication to donation, but the first-line physician would have entrusted the transplant organization with the task of evaluating organ-specific acceptability. Also, this study does not address the question of patient/family consent. The largest impediment to organ procurement after controlled circulatory arrest is relatives’ refusal. Thus, it is important to keep in mind that the rate of refusal would significantly impact the number of potential donors proceeding to donation [40].

Second, while it is not the duration per se but the hemodynamic profile during the withdrawal period which determines the consequences of warm ischemia on organ viability [14], hemodynamic parameters during this period were rarely available due to the observational nature of our study (not influenced by any other purpose than patient’s comfort). Moreover, troublesome monitoring might have been switched off to allow the patient and relatives peace. We arbitrarily considered that an interval of 2 h from treatment withdrawal to cessation of cardiac electrical activity was the maximum timeframe compatible with a hypothetical organ retrieval [14, 15].

Lastly, this study does not address the question of how and when physicians declared death after withdrawal. Theoretical eligibility as organ donors was assessed after death by physicians free of any temporal constraints. Under actual Maastricht III criteria, the removal of organs must be scheduled before withholding/withdrawal is implemented and must start as soon as death is certified. As the removal of organs should not precede the donor’s death, defining the precise moment of death after withdrawal requires the determination of very explicit criteria, even though biological evidence is lacking to support this accuracy [41]. Several organizations state that “if the patient or surrogate understands the circumstances of the determination of death”, physicians are legally authorized to declare death after 2 min of absent circulation [5].

Conclusion

In this observational study, a significant number of patients who died in French ICUs under withholding/withdrawal settings would have been eligible for organ donation based on the assessment of the attending physician. Severely brain-injured patients were more likely to die after the withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in circumstances which may fulfill the requirements for organ retrieval according to Maastricht III.

References

Kutsogiannis DJ, Asthana S, Townsend DR et al (2013) The incidence of potential missed organ donors in intensive care units and emergency rooms: a retrospective cohort. Intensive Care Med 39:1452–1459. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2952-6

Kompanje EJO, Jansen NE, de Groot YJ (2013) “In plain language”: uniform criteria for organ donor recognition. Intensive Care Med 39:1492–1494. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2986-9

Al-Khafaji A, Murugan R, Kellum JA (2013) What’s new in organ donation: better care of the dead for the living. Intensive Care Med 39:2031–2033. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-3038-1

Shemie SD, Baker AJ, Knoll G et al (2010) National recommendations for donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada: donation after cardiocirculatory death in Canada. CMAJ 175(8):S1. doi:10.1503/cmaj.060895

Gries CJ, White DB, Truog RD et al (2013) An official American thoracic society/international society for heart and lung transplantation/society of critical care medicine/association of organ and procurement organizations/united network of organ sharing statement: ethical and policy considerations in organ donation after circulatory determination of death. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 188:103–109. doi:10.1164/rccm.201304-0714ST

British Transplantation Society (2013) United Kingdom Guidelines. Transplantation from donors after deceased circulatory death. Available at: http://www.bts.org.uk/Documents/2013-02-04%20DCD%20guidelines.pdf. Accessed 14 Jul 2014

Organ and Tissue Authority, Australian National Government (2010) Protocol for donation after cardiac death. Available at: http://www.donatelife.gov.au/national-protocol-donation-and-cardiac-death. Accessed 14 Jul 2014

Kootstra G, Daemen JH, Oomen AP (1995) Categories of non-heart-beating donors. Transplant Proc 27:2893–2894

Cabrol C (2007) Organ procurement from non-heart-beating donors. Bull Acad Natl Méd 191:633–638. Available at: http://www.academie-medecine.fr/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/2007.3.pdf. Accessed 14 Jul 2014

Comité Consultatif National d’Ethique pour les sciences de la vie et de la santé (2011) Avis n°115: questions d’éthique relatives au prélèvement et au don d’organes à des fins de transplantation. Available at: http://www.ccne-ethique.fr/sites/default/files/publications/avis_115eng_0.pdf. Accessed 14 Jul 2014

Puybasset L, Bazin J-E, Beloucif S et al (2014) Critical appraisal of organ procurement under Maastricht 3 condition. Ann Fr Anesth Réanimation 33:120–127. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2013.11.004

Graftieaux J-P, Bollaert P-E, Haddad L et al (2012) Contribution of the ethics committee of the French Intensive Care Society to describing a scenario for implementing organ donation after Maastricht type III cardiocirculatory death in France. Ann Intensive Care 2:23. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-2-23

Antoine C, Mourey F, Prada-Bordenave E, Steering committee on DCD program, (2014) How France launched its donation after cardiac death program. Ann Fr Anesth Réanimation 33:138–143. doi:10.1016/j.annfar.2013.11.018

Bradley JA, Pettigrew GJ, Watson CJ (2013) Time to death after withdrawal of treatment in donation after circulatory death (DCD) donors. Curr Opin Organ Transplant 18:133–139. doi:10.1097/MOT.0b013e32835ed81b

Suntharalingam C, Sharples L, Dudley C et al (2009) Time to cardiac death after withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in potential organ donors. Am J Transplant 9:2157–2165. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02758.x

Journal Officiel de la République Française du 23 avril 2005 (2005) Loi n° 2005-370 du 22 avril 2005 relative aux droits des malades et à la fin de vie. Available at: http://www.legifrance.gouv.fr. Accessed 14 Jul 2014

Manara AR, Murphy PG, O’Callaghan G (2012) Donation after circulatory death. Br J Anaesth 108:108–121. doi:10.1093/bja/aer357

Detry O, Laureys S, Faymonville M-E et al (2008) Organ donation after physician-assisted death. Transpl Int 21:915–915. doi:10.1111/j.1432-2277.2008.00701.x

Smith TJ, Vota S, Patel S et al (2012) Organ donation after cardiac death from withdrawal of life support in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Palliat Med 15:16–19. doi:10.1089/jpm.2011.0239

Lesieur O, Mamzer M-F, Leloup M et al (2013) Eligibility of patients withheld or withdrawn from life-sustaining treatment to organ donation after circulatory arrest death: epidemiological feasibility study in a French Intensive Care Unit. Ann Intensive Care 3:36. doi:10.1186/2110-5820-3-36

Wind J, Snoeijs MGJ, Brugman CA et al (2012) Prediction of time of death after withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment in potential donors after cardiac death. Crit Care Med 40:766–769. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e318232e2e7

DeVita MA, Brooks MM, Zawistowski C et al (2008) Donors after cardiac death: validation of identification criteria (DVIC) study for predictors of rapid death. Am J Transplant 8:432–441. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02087.x

Rabinstein AA, Yee AH, Mandrekar J et al (2012) Prediction of potential for organ donation after cardiac death in patients in neurocritical state: a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol 11:414–419. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70060-1

Forte DN, Vincent JL, Velasco IT, Park M (2012) Association between education in EOL care and variability in EOL practice: a survey of ICU physicians. Intensive Care Med 38:404–412. doi:10.1007/s00134-011-2400-4

Wilkinson DJC, Truog RD (2013) The luck of the draw: physician-related variability in end-of-life decision-making in intensive care. Intensive Care Med 39:1128–1132. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2871-6

Wilson ME, Rhudy LM, Ballinger BA et al (2013) Factors that contribute to physician variability in decisions to limit life support in the ICU: a qualitative study. Intensive Care Med 39:1009–1018. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2896-x

Cook D, Rocker G (2014) Dying with Dignity in the Intensive Care Unit. N Engl J Med 370:2506–2514. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1208795

Rady MY, Verheijde JL (2013) The science and ethics of withdrawing mechanical positive pressure ventilatory support in the terminally ill. J Palliat Med 16:828–830. doi:10.1089/jpm.2013.0166

Wilkinson D, Savulescu J (2014) A costly separation between withdrawing and withholding treatment in intensive care. Bioethics 28:127–137. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8519.2012.01981.x

Kompanje EJO, van der Hoven B, Bakker J (2008) Anticipation of distress after discontinuation of mechanical ventilation in the ICU at the end of life. Intensive Care Med 34:1593–1599. doi:10.1007/s00134-008-1172-y

Price D (2011) End-of-life treatment of potential organ donors: paradigm shifts in intensive and emergency care. Med Law Rev 19:86–116. doi:10.1093/medlaw/fwq032

Coggon J (2013) Elective ventilation for organ donation: law, policy and public ethics. J Med Ethics 39:130–134. doi:10.1136/medethics-2012-100992

Davila D, Ciria R, Jassem W et al (2012) Prediction models of donor arrest and graft utilization in liver transplantation from Maastricht-3 donors after circulatory death. Am J Transplant 12:3414–3424. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2012.04242.x

De Groot YJ, Lingsma HF, Bakker J et al (2012) External validation of a prognostic model predicting time of death after withdrawal of life support in neurocritical patients. Crit Care Med 40:233–238. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e31822f0633

Epker JL, Bakker J, Kompanje EJO (2011) The use of opioids and sedatives and time until death after withdrawing mechanical ventilation and vasoactive drugs in a Dutch Intensive Care Unit. Anesth Analg 112:628–634. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e31820ad4d9

Brieva J, Coleman N, Lacey J et al (2013) Prediction of death in less than 60 minutes following withdrawal of cardiorespiratory support in ICUs. Crit Care Med 41:2677–2687. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182987f38

Lewis J, Peltier J, Nelson H et al (2003) Development of the University of Wisconsin donation after cardiac death evaluation tool. Prog Transplant 13:265–273

Cooke CR, Hotchkin DL, Engelberg RA et al (2010) Predictors of time to death after terminal withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in the ICU. Chest 138:289–297. doi:10.1378/chest.10-0289

Pine JK, Goldsmith PJ, Ridgway DM et al (2010) Predicting donor asystole following withdrawal of treatment in donation after cardiac death. Transplant Proc 42:3949–3950. doi:10.1016/j.transproceed.2010.09.080

Shaw D, Elger B (2014) Persuading bereaved families to permit organ donation. Intensive Care Med 40:96–98. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-3096-4

Shemie SD, Hornby L, Baker A et al (2014) International guideline development for the determination of death. Intensive Care Med 40:788–797. doi:10.1007/s00134-014-3242-7

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the non-profit organizations AADAIRC (Association d’Aide à Domicile aux Insuffisants Respiratoires Chroniques) and Ouest-Transplant. The authors thank Marie-Line Cras and Nicolas Girard for their help in the implementation of the survey.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

On the behalf of the EPILAT study group.

Take-home message: A substantial number of patients who died in French ICUs following the decision to withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatment would have been eligible to donate organs according to Maastricht III. Severely brain-injured patients were more likely to die after the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy under conditions which may satisfy the requirements for organ retrieval and graft viability.

The EPILAT study group:

The EPILAT study group:

Olivier LESIEUR, Réanimation, CH Saint-Louis, 17019 La Rochelle, France; Maxime LELOUP, Réanimation, CH Saint-Louis, 17019 La Rochelle, France; Frédéric GONZALEZ, Réanimation Médico-Chirurgicale, CHU Avicenne, 93000 Bobigny, France; Marie-France MAMZER, EA 4569, Université Paris Descartes, 75006 Paris, France.

Investigators:

Olivier BAUDIN, Réanimation, CH d’Angoulême, 16470 Saint-Michel, France; Martine NYUNGA, Réanimation, CH Victor Provo, 59100 Roubaix, France; Julien CHARPENTIER, Réanimation Médicale, CHU Cochin, 75014 Paris, France; Jean Louis DUBOST, Réanimation, CH René Dubos, 95300 Pontoise, France; Laurent MARTIN LEFEVRE, Réanimation, CHD, 85000 La Roche-sur-Yon, France; Quentin LEVRAT, Réanimation, CH Saint-Louis, 17019 La Rochelle, France; Marina THIRION, Réanimation, CH Victor Dupouy, 95100 Argenteuil, France; Patrice TIROT, Réanimation, CH du Mans, 72037 Le Mans, France; Pascal BEURET, Réanimation, CH de Roanne, 42300 Roanne, France; Maud JONAS, Réanimation Médicale, CHU de Nantes, 44093 Nantes, France; Mickaël MORICONI, Réanimation, CH Cornouaille, 29107 Quimper, France; Jean Philippe RIGAUD, Réanimation, CH de Dieppe, Dieppe 76200, France; Jean Pierre QUENOT, Réanimation Médicale, CHU de Dijon, 21000 Dijon, France; Danielle REUTER, Réanimation Médicale, CHU Saint-Louis, 75010 Paris, France; René ROBERT, Réanimation Médicale, CHU de Poitiers, 86021 Poitiers, France; Nicolas PICHON, Réanimation Polyvalente, CHU Dupuytren, 86042 Limoges, France; Thierry BOULAIN, Réanimation Médicale, CHR d’Orléans, 45000 Orléans, France; Renaud CHOUQUER, Réanimation, CH d’Annecy, 74374 Pringy, France; Antoine AUSSEUR, Réanimation, CH de Cholet, 49300 Cholet, France; Fabrice BRUNEEL, Réanimation, CH de Versailles, 78150 Le Chesnay, France; Caroline PERREAU, Réanimation, CHU de Fort de France, 97261 Fort de France, France; Benjamin ZUBER, CHPOT, CH de Versailles, 78150 Le Chesnay, France; Daniel RATELET, Réanimation, CH de Niort, 79000 Niort, France; Benoit GIRAUD, Réanimation neurochirurgicale, CHU de Poitiers, 86021 Poitiers, France; Xavier TCHENIO, Réanimation, CH de Bourg-en-Bresse, 01012 Bourg-en-Bresse, France; Gérald VIQUESNEL, Réanimation Chirurgicale, CHU de Caen, 14033 Caen, France; Cécile LORY, Réanimation, CH de Guéret, 23011 Guéret, France; Malika BENREZKALLAH, Réanimation, CH de Valenciennes, 59300 Valenciennes, France; Diane FRIEDMAN, Réanimation, CHU Raymond Poincaré, 92380 Garches, France; Jean Paul GOUELLO, Réanimation, CH de Saint Malo, 35400 Saint Malo, France; Thierry VANDERLINDEN, Réanimation, GHICL, 59462 Lomme, France; Michel PINSARD, Réanimation Chirurgicale, CHU de Poitiers, 86021 Poitiers, France; Benoit MISSET, Réanimation, CH Saint Joseph, 75014 Paris, France; Emmanuel ANTOK, Réanimation, CHU Sud Réunion, 97448 Saint Pierre, France; Fabienne PLOUVIER, Réanimation, CH d’Agen, 47000 Agen, France; Didier THEVENIN, Réanimation, CH Dr Schaffner, 62300 Lens, France; Marc-Olivier FISCHER, Réanimation Chirurgie Cardiaque, CHU Caen, 14033 Caen, France; Olivier GONTIER, Réanimation, CH de Chartres, 28630 Le Coudray, France; Marc VINCLAIR, Réanimation Neurochirurgicale, CHU Michallon, 38043 Grenoble, France; Christian MIROLO, Réanimation, CH Sud Essonne, 91152 Etampes, France; François NICOLAS, Réanimation, CH de Châteauroux, 36000 Châteauroux, France; Willy-Serge MFAM, Réanimation Chirurgicale, CHR d’Orléans, 45000 Orléans, France; David PETITPAS, Réanimation, CH de Chalons, 51000 Chalons en Champagne, France.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lesieur, O., Leloup, M., Gonzalez, F. et al. Eligibility for organ donation following end-of-life decisions: a study performed in 43 French intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 40, 1323–1331 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3409-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3409-2