Abstract

Purpose

Amikacin requires pharmacodynamic targets of peak serum concentration (C max) of 8–10 times the minimal inhibitory concentration, corresponding to a target C max of 60–80 mg/L for the less susceptible bacteria. Even with new dosing regimens of 25 mg/kg, 30 % of patients do not meet the pharmacodynamic target. We aimed to identify predictive factors for insufficient C max in a population of critically ill patients.

Methods

Prospective observational monocentric study of patients admitted to a general ICU and requiring a loading dose of amikacin. Amikacin was administered intravenously at the dose of 25 mg/kg of total body weight. Independent determinants of C max < 60 mg/L were identified by mixed model multivariate analysis.

Results

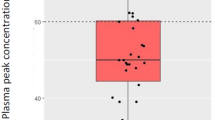

Over a 1-year period, 181 episodes in 146 patients (SAPS 2 = 51 [41–68]) were included. At inclusion, the SOFA score was 8 [6–12], 119 (66 %) episodes required vasopressors, 150 (83 %) mechanical ventilation, and 81 (45 %) renal replacement therapy. The amikacin C max was 69 [54.9–84.4] mg/L. Overall, 60 (33 %) episodes had a C max < 60 mg/L. The risk of C max < 60 mg/L associated with BMI < 25 kg/m2 varied across quarters of inclusion. Independent risk factors for C max < 60 mg/L were a BMI < 25 kg/m2 over the first quarter (odds ratio (OR) 15.95, 95 % confidence interval (CI) [3.68–69.20], p < 0.001) and positive 24-h fluid balance (OR per 250-mL increment 1.06, 95 % [CI 1.01–1.11], p = 0.018).

Conclusions

Despite an amikacin dose of 25 mg/kg of total body weight, 33 % of patients still had an amikacin C max < 60 mg/L. Positive 24-h fluid balance was identified as a predictive factor of C max < 60 mg/L. When total body weight is used, low BMI tended to be associated with amikacin underdosing. These results suggest the need for higher doses in patients with a positive 24-h fluid balance in order to reach adequate therapeutic targets.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A et al (2013) Surviving Sepsis Campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock, 2012. Intensive Care Med 39:165–228. doi:10.1007/s00134-012-2769-8

Ferrer R, Artigas A, Suarez D et al (2009) Effectiveness of treatments for severe sepsis: a prospective, multicenter, observational study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180:861–866. doi:10.1164/rccm.200812-1912OC

Kumar A, Safdar N, Kethireddy S, Chateau D (2010) A survival benefit of combination antibiotic therapy for serious infections associated with sepsis and septic shock is contingent only on the risk of death: a meta-analytic/meta-regression study. Crit Care Med 38:1651–1664. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e96b91

Micek ST, Welch EC, Khan J et al (2010) Empiric combination antibiotic therapy is associated with improved outcome against sepsis due to Gram-negative bacteria: a retrospective analysis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 54:1742–1748. doi:10.1128/AAC.01365-09

Observatoire National de l’Epidémiologie de la Resistance Bactérienne aux Antibiotiques (ONERBA) (2011) Rapport d’activité 2009-10/Annual report 2009-10. www.onerba.org, Vivactis Plus. Accessed 20 Mar 2014

Moore RD, Lietman PS, Smith CR (1987) Clinical response to aminoglycoside therapy: importance of the ratio of peak concentration to minimal inhibitory concentration. J Infect Dis 155:93–99

Zelenitsky SA, Harding GKM, Sun S et al (2003) Treatment and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia: an antibiotic pharmacodynamic analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 52:668–674. doi:10.1093/jac/dkg403

EUCAST (2013) Aminoglycosides: EUCAST clinical MIC breakpoints. http://www.eucast.org/clinical_breakpoints/. Accessed 20 Mar 2014

ANSM (2011) Bon usage des aminosides administrés par voie injectable: gentamicine, tobramycine, netilmicine, amikacine—Mise au point. http://ansm.sante.fr/Mediatheque/Publications/Recommandations-Medicaments. Accessed 20 Mar 2014

Beckhouse MJ, Whyte IM, Byth PL et al (1988) Altered aminoglycoside pharmacokinetics in the critically ill. Anaesth Intensive Care 16:418–422

Marik PE, Havlik I, Monteagudo FS, Lipman J (1991) The pharmacokinetic of amikacin in critically ill adult and paediatric patients: comparison of once- versus twice-daily dosing regimens. J Antimicrob Chemother 27 (Suppl C):81–89

Taccone FS, Laterre P-F, Spapen H et al (2010) Revisiting the loading dose of amikacin for patients with severe sepsis and septic shock. Crit Care 14:R53. doi:10.1186/cc8945

Gálvez R, Luengo C, Cornejo R et al (2011) Higher than recommended amikacin loading doses achieve pharmacokinetic targets without associated toxicity. Int J Antimicrob Agents 38:146–151. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.03.022

Craig W (2010) Amikacin. In: Kucer’s the use of antibiotics, 6th edn. Edward Arnold, London, pp 712–726

Lugo G, Castañeda-Hernández G (1997) Relationship between hemodynamic and vital support measures and pharmacokinetic variability of amikacin in critically ill patients with sepsis. Crit Care Med 25:806–811

de Montmollin E, Gault N, Bouadma L et al (2013) Risk factors for insufficient serum amikacin peak concentrations in critically ill adults. 53rd ICAAC, Denver, Colorado. Category A, 1035

Blaser J, König C, Fatio R et al (1995) Multicenter quality control study of amikacin assay for monitoring once-daily dosing regimens. International Antimicrobial Therapy Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. Ther Drug Monit 17:133–136

Le Gall JR, Lemeshow S, Saulnier F (1993) A new Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS II) based on a European/North American multicenter study. JAMA 270:2957–2963

Knaus WA, Zimmerman JE, Wagner DP et al (1981) APACHE-acute physiology and chronic health evaluation: a physiologically based classification system. Crit Care Med 9:591–597

Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J et al (1996) The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med 22:707–710

Bellomo R, Ronco C, Kellum JA et al (2004) Acute renal failure—definition, outcome measures, animal models, fluid therapy and information technology needs: the Second International Consensus Conference of the Acute Dialysis Quality Initiative (ADQI) Group. Crit Care 8:R204–R212. doi:10.1186/cc2872

Harrell FE Jr, Lee KL, Mark DB (1996) Multivariable prognostic models: issues in developing models, evaluating assumptions and adequacy, and measuring and reducing errors. Stat Med 15:361–387. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19960229)15:4<361:AID-SIM168>3.0.CO;2-4

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E et al (1996) A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 49:1373–1379

Vesin A, Azoulay E, Ruckly S et al (2013) Reporting and handling missing values in clinical studies in intensive care units. Intensive Care Med 39:1396–1404. doi:10.1007/s00134-013-2949-1

Rubin DB, Schenker N (1991) Multiple imputation in health-care databases: an overview and some applications. Stat Med 10:585–598

Pai MP, Bearden DT (2007) Antimicrobial dosing considerations in obese adult patients. Pharmacotherapy 27:1081–1091. doi:10.1592/phco.27.8.1081

Lugo G, Castañeda-Hernández G (1997) Amikacin Bayesian forecasting in critically ill patients with sepsis and cirrhosis. Ther Drug Monit 19:271–276

Pea F, Viale P, Furlanut M (2005) Antimicrobial therapy in critically ill patients: a review of pathophysiological conditions responsible for altered disposition and pharmacokinetic variability. Clin Pharmacokinet 44:1009–1034

Nicolau DP (2003) Optimizing outcomes with antimicrobial therapy through pharmacodynamic profiling. J Infect Chemother 9:292–296. doi:10.1007/s10156-003-0279-x

Cohen P, Collart L, Prober CG et al (1990) Gentamicin pharmacokinetics in neonates undergoing extracorporal membrane oxygenation. Pediatr Infect Dis J 9:562–566

Southgate WM, DiPiro JT, Robertson AF (1989) Pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in neonates on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 33:817–819

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marina Esposito-Farese for statistical advice. The authors would like to thank Jan Devenish for editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Take home message: An amikacin loading dose of 25 mg/kg is insufficient to reach the pharmacodynamic target in 33 % of critically ill patients, in particular in patients with a positive 24-h fluid balance. When total body weight is used, BMI < 25 kg/m2 tended to be associated with amikacin underdosing. This study suggests the need for tight amikacin serum monitoring in every ICU patient, and higher loading doses in this particular subset of patients.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

de Montmollin, E., Bouadma, L., Gault, N. et al. Predictors of insufficient amikacin peak concentration in critically ill patients receiving a 25 mg/kg total body weight regimen. Intensive Care Med 40, 998–1005 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3276-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-014-3276-x