Abstract

Purpose

Response to fluid challenge is often defined as an increase in cardiac index (CI) of more than 10–15%. However, in clinical practice CI values are often not available. We evaluated whether changes in mean arterial pressure (MAP) correlate with changes in CI after fluid challenge in patients with septic shock.

Methods

This was an observational study in which we reviewed prospectively collected data from 51 septic shock patients in whom complete hemodynamic measurements had been obtained before and after a fluid challenge with 1,000 ml crystalloid (Hartman’s solution) or 500 ml colloid (hydroxyethyl starch 6%). CI was measured using thermodilution. Patients were divided into two groups (responders and non-responders) according to their change in CI (responders: %CI >10%) after the fluid challenge. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-way analysis of variance test followed by a Student’s t test with adjustment for multiple comparisons. Pearson’s correlation and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis were also used.

Results

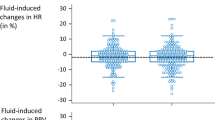

Mean patient age was 67 ± 17 years and mean Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) upon admittance to the intensive care unit was 10 ± 3. In the 25 responders, MAP increased from 69 ± 9 to 77 ± 9 mmHg, pulse pressure (PP) increased from 59 ± 15 to 67 ± 16, and CI increased from 2.8 ± 0.8 to 3.4 ± 0.9 L/min/m2 (all p < 0.001). There were no significant correlations between the changes in MAP, PP, and CI.

Conclusions

Changes in MAP do not reliably track changes in CI after fluid challenge in patients with septic shock and, consequently, should be interpreted carefully when evaluating the response to fluid challenge in such patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vincent JL, Weil MH (2006) Fluid challenge revisited. Crit Care Med 34:1333–1337

Weil MH, Henning RJ (1979) New concepts in the diagnosis and fluid treatment of circulatory shock. Thirteenth annual Becton, Dickinson and Company Oscar Schwidetsky Memorial Lecture. Anesth Analg 58:124–132

Vincent JL, Gerlach H (2004) Fluid resuscitation in severe sepsis and septic shock: an evidence-based review. Crit Care Med 32:S451–S454

Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Carlet JM, Bion J, Parker MM, Jaeschke R, Reinhart K, Angus DC, Brun-Buisson C, Beale R, Calandra T, Dhainaut JF, Gerlach H, Harvey M, Marini JJ, Marshall J, Ranieri M, Ramsay G, Sevransky J, Thompson BT, Townsend S, Vender JS, Zimmerman JL, Vincent JL (2008) Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2008. Intensive Care Med 34:17–60

Monnet X, Teboul JL (2007) Volume responsiveness. Curr Opin Crit Care 13:549–553

Horst HM, Obeid FN (1986) Hemodynamic response to fluid challenge: a means of assessing volume status in the critically ill. Henry Ford Hosp Med J 34:90–94

Coudray A, Romand JA, Treggiari M, Bendjelid K (2005) Fluid responsiveness in spontaneously breathing patients: a review of indexes used in intensive care. Crit Care Med 33:2757–2762

Vincent JL, Pinsky MR, Sprung CL, Levy M, Marini JJ, Payen D, Rhodes A, Takala J (2008) The pulmonary artery catheter: in medio virtus. Crit Care Med 36:3093–3096

Marik PE, Varon J (1998) The hemodynamic derangements in sepsis: implications for treatment strategies. Chest 114:854–860

Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, Abraham E, Angus D, Cook D, Cohen J, Opal SM, Vincent JL, Ramsay G (2003) 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International sepsis definitions conference. Intensive Care Med 29:530–538

Prasso JE, Berberian G, Cabreriza SE, Quinn TA, Curtis LJ, Rabkin DG, Weinberg AD, Spotnitz HM (2005) Validation of mean arterial pressure as an indicator of acute changes in cardiac output. ASAIO J 51:22–25

Monnet X, Letierce A, Hamzaoui O, Chemla D, Anguel N, Osman D, Richard C, Teboul JL (2011) Arterial pressure allows monitoring the changes in cardiac output induced by volume expansion but not by norepinephrine. Crit Care Med 39(6):1394–1399

Hadian M, Kim HK, Severyn DA, Pinsky MR (2010) Cross-comparison of cardiac output trending accuracy of LiDCO, PiCCO, FloTrac and pulmonary artery catheters. Crit Care 14:R212

Monnet X, Chemla D, Osman D, Anguel N, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL (2007) Measuring aortic diameter improves accuracy of esophageal Doppler in assessing fluid responsiveness. Crit Care Med 35:477–482

Sayk F, Vietheer A, Schaaf B, Wellhoener P, Weitz G, Lehnert H, Dodt C (2008) Endotoxemia causes central downregulation of sympathetic vasomotor tone in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 295:R891–R898

Hamzaoui O, Monnet X, Richard C, Osman D, Chemla D, Teboul JL (2008) Effects of changes in vascular tone on the agreement between pulse contour and transpulmonary thermodilution cardiac output measurements within an up to 6-hour calibration-free period. Crit Care Med 36:434–440

Bendjelid K (2009) When to recalibrate the PiCCO? From a physiological point of view, the answer is simple. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 53:689–690

Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA (1992) Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation 86:513–521

Monge Garcia MI, Gil CA, Gracia RM (2011) Dynamic arterial elastance to predict arterial pressure response to volume loading in preload-dependent patients. Crit Care 15:R15

Bennett-Guerrero E, Kahn RA, Moskowitz DM, Falcucci O, Bodian CA (2002) Comparison of arterial systolic pressure variation with other clinical parameters to predict the response to fluid challenges during cardiac surgery. Mt Sinai J Med 69:96–100

Silva E, De Backer D, Creteur J, Vincent JL (2004) Effects of fluid challenge on gastric mucosal PCO2 in septic patients. Intensive Care Med 30:423–429

Michard F, Boussat S, Chemla D, Anguel N, Mercat A, Lecarpentier Y, Richard C, Pinsky MR, Teboul JL (2000) Relation between respiratory changes in arterial pulse pressure and fluid responsiveness in septic patients with acute circulatory failure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 162:134–138

Heenen S, De Backer D, Vincent JL (2006) How can the response to volume expansion in patients with spontaneous respiratory movements be predicted? Crit Care 10:R102

Preisman S, Kogan S, Berkenstadt H, Perel A (2005) Predicting fluid responsiveness in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: functional haemodynamic parameters including the respiratory systolic variation test and static preload indicators. Br J Anaesth 95:746–755

De Backer D, Heenen S, Piagnerelli M, Koch M, Vincent JL (2005) Pulse pressure variations to predict fluid responsiveness: influence of tidal volume. Intensive Care Med 31:517–523

Marik PE, Cavallazzi R, Vasu T, Hirani A (2009) Dynamic changes in arterial waveform derived variables and fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med 37:2642–2647

Michard F, Teboul JL (2002) Predicting fluid responsiveness in ICU patients: a critical analysis of the evidence. Chest 121:2000–2008

Michard F, Alaya S, Zarka V, Bahloul M, Richard C, Teboul JL (2003) Global end-diastolic volume as an indicator of cardiac preload in patients with septic shock. Chest 124:1900–1908

Casserly B, Read R, Levy MM (2009) Hemodynamic monitoring in sepsis. Crit Care Clin 25:803–23, ix

O’Rourke MF, Yaginuma T (1984) Wave reflections and the arterial pulse. Arch Intern Med 144:366–371

Dorman T, Breslow MJ, Lipsett PA, Rosenberg JM, Balser JR, Almog Y, Rosenfeld BA (1998) Radial artery pressure monitoring underestimates central arterial pressure during vasopressor therapy in critically ill surgical patients. Crit Care Med 26:1646–1649

Hatib F, Jansen JR, Pinsky MR (2011) Peripheral vascular decoupling in porcine endotoxic shock. J Appl Physiol 111:853–860

Dufour N, Chemla D, Teboul JL, Monnet X, Richard C, Osman D (2011) Changes in pulse pressure following fluid loading: a comparison between aortic root (non-invasive tonometry) and femoral artery (invasive recordings). Intensive Care Med 37:942–949

Gravlee GP, Wong AB, Adkins TG, Case LD, Pauca AL (1989) A comparison of radial, brachial, and aortic pressures after cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Anesth 3:20–26

Kanazawa M, Fukuyama H, Kinefuchi Y, Takiguchi M, Suzuki T (2003) Relationship between aortic-to-radial arterial pressure gradient after cardiopulmonary bypass and changes in arterial elasticity. Anesthesiology 99:48–53

Stern DH, Gerson JI, Allen FB, Parker FB (1985) Can we trust the direct radial artery pressure immediately following cardiopulmonary bypass? Anesthesiology 62:557–561

Mignini MA, Piacentini E, Dubin A (2006) Peripheral arterial blood pressure monitoring adequately tracks central arterial blood pressure in critically ill patients: an observational study. Crit Care 10:R43

Vincent JL, Rhodes A, Perel A, Martin GS, Rocca GD, Vallet B, Pinsky MR, Hofer CK, Teboul JL, de Boode WP, Scolletta S, Vieillard-Baron A, De Backer D, Walley KR, Maggiorini M, Singer M (2011) Clinical review: update on hemodynamic monitoring—a consensus of 16. Crit Care 15:229

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pierrakos, C., Velissaris, D., Scolletta, S. et al. Can changes in arterial pressure be used to detect changes in cardiac index during fluid challenge in patients with septic shock?. Intensive Care Med 38, 422–428 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2457-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2457-0