Abstract

Purpose

To investigate differences in cytokine/chemokine release in response to lipoteichoic acid (LTA) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and contributing cellular mechanisms, in order to improve understanding of the pathogenesis of sepsis.

Methods

Levels of cytokines/chemokines were measured in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid of 10-week-old male mice (C57/B16) following intraperitoneal injection of LTA or LPS (250 µg), and in supernatants of murine J774.2 cells, immortalised blood monocytes, or isolated human monocytes treated with LTA or LPS (0–10 µg/ml). The role of cytokine/chemokine messenger RNA (mRNA) stability versus nuclear factor-kappaB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1) in mediating cytokine/chemokine release in J774 cells was also assessed.

Results

In mice, plasma levels of keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC), macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2, interleukin (IL)-10, interferon (IFN)-γ and tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and peritoneal lavage fluid levels of KC, MIP-2 and TNF-α increased significantly 1 h after LPS. Only KC and MIP-2 levels increased 1 h after LTA. LPS-treated (10 μg/ml) J774 cells released MIP-2, IL-10, IFN-γ and TNF-α but not KC (24 h), whereas cells treated with 10 μg/ml LTA released only MIP-2. LPS-stimulated human monocytes released IL-10 and IL-8 (24 h); by contrast, LTA-treated cells released only IL-8. LPS and LTA activated NF-κB and AP-1 in J774 cells. The protein synthesis inhibitor cycloheximide abolished LPS-induced IL-10 mRNA expression and increased LTA- and LPS-induced mRNA for MIP-2 in J774 cells.

Conclusion

LTA and LPS, at clinically relevant concentrations, induced differential cytokine/chemokine release in vitro and in vivo, via effects distal to activation of NF-κB/AP-1 that might include chromatin remodelling or mRNA stability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Sepsis and its sequelae are the leading causes of death among critically ill patients [1]. Treatment is largely supportive following source control and administration of antibiotics. Sepsis is associated with uncontrolled and excessive cytokine release. However, potential therapeutic intervention targeted at cytokines has failed to reduce mortality in multiple clinical trials [2]. These failures likely reflect the molecular complexity and redundancy within the inflammatory response [2] and the extent to which an infecting organism dictates the response [3, 4]. In this regard, distinct patterns of cytokine and leucocyte gene expression have been shown for Gram-positive and Gram-negative organisms [5] and activation of their respective receptor pathways, Toll-like receptor (TLR)2 and TLR4 [6]. Understanding the cellular mechanisms that account for these differences could, ultimately, aid the development of novel and effective pharmacotherapies.

Lipoteichoic acid (LTA) is a cell wall component exclusive to Gram-positive bacteria and is shed during bacterial replication and after antibiotic administration [7, 8]. LTA is the functional equivalent to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), the major cell wall component of Gram-negative bacteria. Whilst numerous in vivo studies have shown that LPS triggers cytokine release in rodent models and humans, fewer studies have investigated the effects of LTA in vivo [9–11].

The aims of the present study are fourfold: first, to compare in a rodent model the effects of intraperitoneal (ip) LTA and LPS on release of the cytokines TNF-α, interferon (IFN)-γ and interleukin (IL)-10, and also the CXC neutrophil chemokines, macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 and keratinocyte-derived chemokine (KC). Secondly, to measure cytokine/chemokine release from the murine J774.2 monocyte/macrophage cell line following exposure to LPS or LTA. Thirdly, to measure, in LPS- and LTA-activated human monocytes, release of IL-10 and IL-8, a human CXC chemokine analogous to MIP-2/KC. Finally, we investigated mechanisms mediating release of these cytokines/chemokines by examining the activation of cell signalling moieties relevant to the process.

Materials and methods

Bacterial products

LPS from Escherichia coli (O55:B5) was re-purified before use [12] and quantified using the Limulus amoebocyte lysate assay (BioWhitaker, Belgium). Pure LTA was extracted in butanol at room temperature from Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus, serotype DSM 2033, gift from Prof. T. Hartung, University of Konstanz). The method of extraction is key, since hot phenol extraction of LTA strips the native molecule of its alanine residues and biological activity [13, 14]. Ligands were screened for purity using primary human embryonic kidney cells stably transfected with tlr4 or tlr2/6 (data not shown).

Murine model

Ten-week-old mice (C57/B16) were housed under specific, pathogen-free conditions and used in experiments performed using UK licensing agreements. After intraperitoneal administration of vehicle, LPS, or LTA, the peritoneal cavity was lavaged using ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline. Blood was obtained via the inferior vena cava.

Cell culture

The murine monocyte/macrophage cell line J774.2 (referred to as J774 cells) was cultured as described previously [15].

Human peripheral blood monocytes

Blood was taken according to a Local Research Ethics Committee-approved protocol. Monocytes were separated from granulocytes using discontinuous Percoll density gradient (55%, 68% and 81%) centrifugation and an indirect magnetic labelling system (Monocyte Isolation Kit II; Miltenyi Biotec, Germany).

Cytokine assays

A multiplex immunoassay was established to measure multiple soluble analytes in small quantities (50 μl) of murine plasma, lavage fluid or cell culture supernatants. Standard concentrations of cytokine/chemokine were used to calibrate the assay and cytokine concentrations calculated from Alexa 488 measurements. For samples employing human cells, cytokine assays were performed using commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs; R & D Systems Europe Ltd, UK).

Quantitative RT-PCR analysis

mRNA transcript levels for IL-10 and MIP-2 were evaluated using quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and a Rotor-Gene 3000TM four-channel multiplex system. IL-10 and MIP-2 mRNA levels were measured and expressed as a ratio to the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) reference gene.

Transcription factor activity ELISA measurements

Nuclear extracts of J774 cells were prepared, and ELISA-based kits (TransAM; ActiveMotif, Belgium) used to assess NF-κB p50 and p65 and AP-1 c-Jun binding activity. Results were expressed as optical density (OD)405 per milligram protein. J774 cells were also assessed for nuclear translocation of p65, p50 and c-Jun using immuno-fluorescence staining and confocal microscopy [see Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM)].

Experimental protocols

In mice, LPS (250 μg, ~10 mg/kg), LTA (250 μg, ~10 mg/kg) or an equivalent volume of sterile 0.9% saline vehicle (250 μl) was administered intraperitoneally. The dose of LPS used equated to the mid-point of those used by other investigators [16–18]. An identical dose of LTA was employed, as LPS and LTA have similar potency assessed using MIP2 release from J774 cells as an endpoint. We have previously shown LTA to have biological activity in vivo at a dose of ~4 mg/kg [13]. Animals were euthanised 0, 1, 3 or 6 h later. Subsequently, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10, MIP-2 and KC were measured using the multiplexed assay in peritoneal lavage and plasma. In parallel studies, J774 cells were activated with LPS (0–10 μg/ml) or LTA (0–10 μg/ml) and the same cytokines/chemokines measured in cell culture supernatants at 24 h (for justification of doses see ESM). The mRNA transcript levels for IL-10 and MIP-2 were also evaluated at 4 h. Human peripheral blood monocytes were stimulated with LPS (0–10 μg/ml) and LTA (0–20 μg/ml) and an equivalent chemokine (IL-8) and IL-10 assayed, again at 24 h.

To investigate whether differences in activation of the transcription factors NF-κB and AP-1 might contribute to differences identified in LPS- and LTA-induced MIP-2 and IL-10 release, J774 cells were incubated for 1 h with medium, LPS (3 μg/ml) or LTA (10 μg/ml), or TNF-α and IFN-γ (as controls) prior to quantification of activated transcription factors (and immuno-fluorescent staining; see ESM). Also, chemokine and cytokine release was assessed after pharmacological inhibition of the AP-1 pathway with the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) inhibitor (see ESM). Finally, to investigate the possible contribution of stabilising/destabilising proteins to mRNA transcript levels for IL-10 and MIP-2, de novo protein synthesis was inhibited using cycloheximide (CXH, 0.1 μg/ml) administered for 10 min prior to the addition of LPS or LTA.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of n experiments. Statistical analysis was carried out using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Dunnett’s post test unless otherwise stated. Data were log transformed for in vivo experiments before analysis due to disparate inter-group variances. Results were deemed significant for p < 0.05.

Results

LTA and LPS induce different patterns of cytokine/chemokine release in mice

There were no deaths in either the LPS or LTA groups. LPS (250 μg ip) significantly increased plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid levels of MIP-2 and KC at 1, 3 and 6 h. LTA (250 μg ip) also significantly increased peritoneal lavage fluid and plasma levels of MIP-2 and KC, albeit only at 1 h and to a lesser extent than LPS (Fig. 1).

LTA and LPS cause different profiles of cytokine/chemokine release in mice than LPS. Concentrations of MIP and KC or of TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 were measured in plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid at 0, 1, 3 and 6 h after intraperitoneal injection of saline vehicle (250 μl, control), LPS (250 μg) or LTA (250 μg). Data are presented as mean ± SEM from 4–6 independent experiments, each conducted in a separate animal with individually prepared experimental stimuli. Some time points represent only four data points because occasional loss of multiplexing beads during immunoassay meant data were not available. Data were log transformed prior to analysis due to disparate inter-group variances. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 compared with t = 0 and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test

Whilst plasma levels of cytokines increased significantly following LPS injection (250 μg ip) (specifically, TNF-α, IFN-γ and IL-10 by 1 h, IFN-γ also at 6 h, and IL-10 at 3 and 6 h), the direction of change in peritoneal lavage fluid levels after LPS injection depended on the cytokine (Fig. 1). Thus, TNF-α levels increased significantly at 1 h following LPS (and also at 6 h in the control group), IL-10 decreased significantly compared with saline control at 1 and 3 h, and changes in IFN-γ levels were not statistically significant. LTA (250 μg ip) had no measurable effects on cytokine levels in plasma or peritoneal lavage (Fig. 1).

LTA and LPS induce different patterns of cytokine/chemokine release in cultured monocytes

LPS (0–10 μg/ml) caused a significant release of MIP-2 (a CXC chemokine), TNF-α and IFN-γ, a significant release of IL-10 with LPS at 10 μg/ml, but no release of another CXC chemokine KC (Fig. 2). LTA (1–10 μg/ml) induced MIP-2 release but had no effect on KC, TNF-α, IFN-γ or IL-10 release (Fig. 2). Co-administration of LPS (0.1 μg/ml) with LTA facilitated IL-10 release, whereby increasing concentrations of LTA induced increasing amounts of IL-10 (Fig. 2). Zymosan, another putative TLR2 agonist, induced MIP-2 release from J774 cells but had no effect on KC, TNF-α, IFN-γ or IL-10 release (data not shown). The effects of LPS and LTA on MIP-2 release were paralleled in isolated human monocytes. LPS (0.1–10 μg/ml) and LTA (1–20 μg/ml) induced significant and similar release of IL-8. LPS induced IL-10 release, but LTA had no effect (Fig. 3).

LTA and LPS cause different profiles of cytokine/chemokine release in J774 cells. Concentrations of MIP, KC, TNFα, IFN-γ and IL-10 were measured in cell supernatants at 24 h following exposure to LPS (0.03–10 μg/ml) or LTA (0.03–10 μg/ml), and IL-10 after exposure to LTA (0.03–10 μg/ml) plus LPS (0.1 μg/ml). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with medium alone (0) and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test, or **p < 0.01 between equivalent bars in groups with a line above when analysed by two-way ANOVA

LPS induced IL-8 and IL-10 and LTA induced IL-8 release from isolated human monocytes. Cytokine concentrations were measured in cell supernatants at 24 h following exposure to LPS (0.01–10 μg/ml) or LTA (1–20 μg/ml). Data are presented as mean ± SEM of three separate experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with medium alone (0) and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test

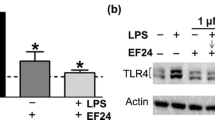

LTA and LPS increase active nuclear p65 and c-Jun in J774 cells

LPS (3 µg/ml) and LTA (10 µg/ml) significantly increased nuclear binding activity of p65 and c-Jun at 1 h as assessed using TransAm transcription factor binding assays and when compared with transcription factor activity of subunits extracted from untreated cells (Fig. 4). LTA and LPS also increased nuclear translocation of p65 and c-Jun, and JNK and inhibitor of kappaB kinase-β (IKK-β) inhibitors reduced LTA- and LPS-induced chemokine/cytokine release in J774 cells (see ESM).

LPS and LTA caused nuclear activation of NF-κB and AP-1. p65 and c-Jun binding activity in J774 cells was measured using the TransAM commercial assay. J774 cells were treated for 1 h with LPS (3 μg/ml) or LTA (10 μg/ml), or medium alone. HeLa cell extract was used as a positive control (Pos). Specificity was shown by inhibiting binding using excess oligonucleotide with a single base pair mutation of the consensus sequence (Mut) compared with wild-type oligonucleotide (WT). Data are presented for five separate experiments; **p < 0.01 compared with medium and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test

Contrasting effects of cycloheximide on IL-10 and MIP-2 mRNA in J774 cells

Pre-treatment (10 min) of J774 cells with CXH (0.1 μg/ml) abolished LPS-induced IL-10 mRNA (4 h) production, whereas the lack of effect of LTA on IL-10 mRNA was not altered (Fig. 5). By contrast, LPS and LTA increased MIP-2 mRNA in J774 cells and each was further increased with CXH (Fig 5).

Comparison of the effect of LPS and LTA on IL-10 or MIP-2 mRNA levels in J774 cells. MIP-2 and IL-10 concentrations were measured in J774 cell culture supernatants at 24 h. J774 cells were pre-incubated with CXH (0.1 μg/ml, 10 min), followed by LPS (1 μg/ml) or LTA (10 μg/ml) for 4 h. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with medium alone (0) and analysed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test

Discussion

Our study shows differences in expression of cytokine/chemokine release, in vitro and in vivo, in response to LPS compared with LTA, at clinically relevant concentrations. Thus, ip injection of 10 mg/kg LPS into mice increased plasma and peritoneal lavage fluid levels of MIP-2, KC and TNF-α. The cytokines IL-10 and IFN-γ increased in peritoneal lavage only. By contrast, ip injection of 10 mg/kg LTA only increased levels of plasma and peritoneal KC and MIP-2, and to a lesser extent than LPS. LPS resulted in a fall in plasma IL-10; it is not known whether this relates to decreased basal production, increased elimination or dilution by intravascular fluid shifts. It is possible that the reduction in this anti-inflammatory cytokine may in part contribute to the increase in MIP-2, KC, TNF-α and IFN-γ.

LPS induced release from J774 cells of MIP-2 and TNF-α with 0.031 µg/ml, IFN-γ with 0.1 µg/ml, IL-10 with 10 µg/ml LPS, and IL-8 and IL-10 from human monocytes with 0.1 and 1 µg/ml LPS, respectively. By contrast, LTA (0.3–10 µg/ml) only induced MIP-2 release from J774 cells and IL-8 from human monocytes (using 1–20 µg/ml LTA). Despite these differences, LPS and LTA both induced NF-κB and AP-1 nuclear translocation and activity in J774 cells (at 3 and 10 µg/ml, respectively), and inhibitors of these signalling pathways reduced cytokine/chemokine release (ESM). At the mRNA level, we showed that CXH, an inhibitor of de novo protein synthesis, enhanced LPS- and LTA-induced MIP-2 mRNA, abolished LPS-induced IL-10 mRNA, but did not override the lack of effect of LTA on IL-10 mRNA. These novel findings suggest that CXH-sensitive regulatory proteins operative at the level of mRNA, rather than disparity in NF-κB and AP-1 translocation/activation, might, at least in part, account for differences in LPS- and LTA-induced cytokine/chemokine expression.

The more extensive effects on chemokine/cytokine induction, in vivo, of LPS compared with LTA that we have shown reflect findings of others [10, 19]. Intranasal administration of LTA produced lower KC and MIP-2 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of mice at 6 h, compared with LPS [10]. Also, instillation of LPS, but not LTA, into lungs of healthy volunteers increased chemokine/cytokine levels at 6 h [9, 19]. The inability of LTA to induce IFN-γ, in vivo, in our study, is consistent with a previous finding that LTA was toxic in galactosamine-treated mice only when IFN-γ was pre-administered, suggesting that LTA did not induce IFN-γ [20]. However, the lack of effect of LTA on TNF-α levels in peritoneal lavage in our study contrasts with findings of TNF-α in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of mice [21–23] following LTA administration. One explanation for the difference might be a greater density of target cells, particularly alveolar macrophages, in the lung compared with the peritoneum.

The profile of LPS- and LTA-induced release of chemokines/cytokines in vivo in our study was similar to effects in vitro. The exception was KC, which was released, in vivo, in quantifiably similar amounts to MIP-2 but was un-detectable in J774 cells. Others have shown that LPS induced release of KC from J774 cells at levels (~20 pg/ml) below the sensitivity of the assay we employed [24]. A lack of KC induction in J774 cells might reflect an alternative source of KC in the intraperitoneal model such as fibroblasts [25], rather than a problem with immortalised J774 macrophages.

Differences in our study between LPS- and LTA-induced cytokines in vitro concur with previous findings. Microarray analysis of whole blood activated with LPS or heat-killed S. aureus showed stimulus-dependent patterns of cytokine appearance and leucocyte gene expression [5]. Another microarray study in tammar mammary epithelial cells showed that LTA induced lower levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines when compared with LPS [26]. Similarly, in a range of human and murine cells, LTA was consistently less potent than LPS in causing cytokine/chemokine release [27]. More specifically, S. epidermidis LTA was 100-fold less active than E. coli LPS at inducing IL-6, TNF and IL-1 release in J774 cells [28] and LTA a less potent inducer of IL-1 and IL-8 release from feline whole blood [29]. The lack of effect of LTA on IL-10 release from J774 cells in our study also concurs with previous findings [30]. A single report showing that LTA released IL-10 from purified human monocytes acknowledged that contamination of the LTA with LPS was a likely explanation [31].

Differences between LTA and LPS, in terms of cytokine release, in vivo and in vitro, mirror results from clinical studies comparing Gram-positive and Gram-negative infections. Plasma levels of IL-10 are lower in patients with Gram-positive compared with Gram-negative sepsis, although not consistently [32], and IL-1, IL-6 and IL-18 levels have been reported as significantly higher [5]. Together these studies suggest that, clinically, differences in cytokine release are dependent on the nature of the infection.

Differences in cytokine/chemokine release, in vivo and in vitro, could not, at least in our study, be explained in terms of differences in activation of key elements of canonical inflammatory signalling pathways, specifically NF-κB and AP-1. As others have before, we showed equipotent induction of NF-κB with LPS and LTA [27]. NF-κB activation in monocyte/macrophages with LPS and LTA is well recognised [33], as is LPS activation of AP-1 [34]. Whilst LTA activation of AP-1 in human synovial fibroblasts has been shown [35], to our knowledge, ours is the first study to show activation of AP-1 in monocytes with pure LTA. Pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB and AP-1 implicated these pathways in MIP-2 and IL-10 release (ESM). The lack of effect of AP-1 inhibition on LPS-induced MIP-2 release contrasts with a previous finding that showed SP600125 inhibited MIP-2 release from RAW 264.7 cells, a monocyte cell line [36]. The difference might, at least in part, be explained by our inability to use SP600125 above 10 μM because of cytotoxic effects in J774 cells.

That LTA did not induce IL-10 release from either J774 cells or human monocytes when it activated NF-κB and AP-1, pathways linked to IL-10 release, prompted us to measure IL-10 mRNA levels in J774 cells. The finding that LPS, but not LTA, induced IL-10 mRNA expression, mirroring differences in protein release, gave rise to a number of speculations. First an, as yet, unidentified transcription factor might contribute to LPS-induced effects. Against this, the physical size of the transcription factor complex already known to contain AP-1, NF-κB, specificity protein-1 (Sp-1), general transcription factors and RNA polymerase II could rule this out. Alternatively, LPS but not LTA could influence pathways that impact on either the generation of mRNA or its stability. The finding that CXH abolished LPS-induced IL-10 mRNA suggests that CXH-sensitive proteins facilitated transcription of or stabilised IL-10 mRNA, evidently being proteins that LTA could not induce. By contrast, CXH super-induction of LTA- and LPS-induced MIP-2 mRNA suggests that these stimuli induced proteins that either limit transcription or reduce the stability of mRNA. However, our experiments are unable to show whether the effect is pre- or post-transcriptional. In this regard, others showed that LPS stimulation was associated with nucleosome/chromatin remodelling at the IL-12 p40 promoter [37], an event necessary for transcription factor binding and subsequent transcription. Alternatively, we have shown previously that LTA can have a post-transcriptional effect, reducing IL-8 mRNA half-life in human endothelial cells [38]. In support of an effect at the mRNA level is the observation that co-administration of LTA and LPS resulted in greater IL-10 production. We propose that greater understanding of the nature of cytokine regulation at the mRNA level and the similarities and dissimilarities between Gram-positive and Gram-negative stimuli, at this juncture, might well provide novel therapeutic and more targeted avenues for treatment of sepsis in the future.

References

Angus DC, Linde-Zwirble WT, Lidicker J, Clermont G, Carcillo J, Pinsky MR (2001) Epidemiology of severe sepsis in the United States: analysis of incidence, outcome, and associated costs of care. Crit Care Med 29:1303–1310

Zanotti S, Kumar A (2002) Cytokine modulation in sepsis and septic shock. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 11:1061–1075

Fisher CJ Jr, Agosti JM, Opal SM, Lowry SF, Balk RA, Sadoff JC, Abraham E, Schein RM, Benjamin E (1996) Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein. The soluble TNF receptor sepsis study group. N Engl J Med 334:1697–1702

Moreno RP, Metnitz B, Adler L, Hoechtl A, Bauer P, Metnitz PG (2008) Sepsis mortality prediction based on predisposition, infection and response. Intensive Care Med 34:496–504

Feezor RJ, Oberholzer C, Baker HV, Novick D, Rubinstein M, Moldawer LL, Pribble J, Souza S, Dinarello CA, Ertel W, Oberholzer A (2003) Molecular characterization of the acute inflammatory response to infections with gram-negative versus gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun 71:5803–5813

Lorne E, Dupont H, Abraham E (2010) Toll-like receptors 2 and 4: initiators of non-septic inflammation in critical care medicine? Intensive Care Med 36:1826–1835

Markham JL, Knox KW, Wicken AJ, Hewett MJ (1975) Formation of extracellular lipoteichoic acid by oral streptococci and lactobacilli. Infect Immun 12:378–386

van Langevelde P, van Dissel JT, Ravensbergen E, Appelmelk BJ, Schrijver IA, Groeneveld PH (1998) Antibiotic-induced release of lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus: quantitative measurements and biological reactivities. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 42:3073–3078

Leemans JC, Vervoordeldonk MJ, Florquin S, van Kessel KP, van der Poll T (2002) Differential role of interleukin-6 in lung inflammation induced by lipoteichoic acid and peptidoglycan from Staphylococcus aureus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:1445–1450

van Zoelen MA, de Vos AF, Larosa GJ, Draing C, von Aulock S, van der Poll T (2007) Intrapulmonary delivery of ethyl pyruvate attenuates lipopolysaccharide- and lipoteichoic acid-induced lung inflammation in vivo. Shock 28:570–575

Draing C, Sigel S, Deininger S, Traub S, Munke R, Mayer C, Hareng L, Hartung T, von Aulock S, Hermann C (2008) Cytokine induction by gram-positive bacteria. Immunobiology 213:285–296

Manthey CL, Perera PY, Henricson BE, Hamilton TA, Qureshi N, Vogel SN (1994) Endotoxin-induced early gene expression in C3H/HeJ (Lpsd) macrophages. J Immunol 153:2653–2663

Finney SJ, Anning PB, Cao TV, Perretti M, Evans TW, Burke-Gaffney A (2007) Butanol-extracted lipoteichoic acid induces in vivo leukocyte adhesion. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 364:831–837

Morath S, Stadelmaier A, Geyer A, Schmidt RR, Hartung T (2002) Synthetic lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus is a potent stimulus of cytokine release. J Exp Med 195:1635–1640

Baydoun AR, Bogle RG, Pearson JD, Mann GE (1993) Selective inhibition by dexamethasone of induction of NO synthase, but not of induction of l-arginine transport, in activated murine macrophage J774 cells. Br J Pharmacol 110:1401–1406

Delgado M, Ganea D (2001) Inhibition of endotoxin-induced macrophage chemokine production by VIP and PACAP in vitro and in vivo. Arch Physiol Biochem 109:377–382

Koay MA, Christman JW, Segal BH, Venkatakrishnan A, Blackwell TR, Holland SM, Blackwell TS (2001) Impaired pulmonary NF-kappaB activation in response to lipopolysaccharide in NADPH oxidase-deficient mice. Infect Immun 69:5991–5996

Cheng SS, Lukacs NW, Kunkel SL (2002) Eotaxin/CCL11 is a negative regulator of neutrophil recruitment in a murine model of endotoxemia. Exp Mol Pathol 73:1–8

Hoogerwerf JJ, de Vos AF, Bresser P, van der Zee JS, Pater JM, de Boer A, Tanck M, Lundell DL, Her-Jenh C, Draing C, von Aulock S, van der Poll T (2008) Lung inflammation induced by lipoteichoic acid or lipopolysaccharide in humans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 178:34–41

Hermann C, Spreitzer I, Schroder NW, Morath S, Lehner MD, Fischer W, Schutt C, Schumann RR, Hartung T (2002) Cytokine induction by purified lipoteichoic acids from various bacterial species–role of LBP, sCD14, CD14 and failure to induce IL-12 and subsequent IFN-gamma release. Eur J Immunol 32:541–551

Yamamoto S, Tin Tin Win S, Ahmed S, Kobayashi T, Fujimaki H (2006) Effect of ultrafine carbon black particles on lipoteichoic acid-induced early pulmonary inflammation in BALB/c mice. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 213:256–266

Knapp S, von Aulock S, Leendertse M, Haslinger I, Draing C, Golenbock DT, van der Poll T (2008) Lipoteichoic acid-induced lung inflammation depends on TLR2 and the concerted action of TLR4 and the platelet-activating factor receptor. J Immunol 180:3478–3484

Jiao YL, Wu MP (2008) Apolipoprotein A-I diminishes acute lung injury and sepsis in mice induced by lipoteichoic acid. Cytokine 43:83–87

McDonald PP, Fadok VA, Bratton D, Henson PM (1999) Transcriptional and translational regulation of inflammatory mediator production by endogenous TGF-beta in macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells. J Immunol 163:6164–6172

Bozic CR, Kolakowski LF Jr, Gerard NP, Garcia-Rodriguez C, von Uexkull-Guldenband C, Conklyn MJ, Breslow R, Showell HJ, Gerard C (1995) Expression and biologic characterization of the murine chemokine KC. J Immunol 154:6048–6057

Daly KA, Mailer SL, Digby MR, Lefevre C, Thomson P, Deane E, Nicholas KR, Williamson P (2009) Molecular analysis of tammar (Macropus eugenii) mammary epithelial cells stimulated with lipopolysaccharide and lipoteichoic acid. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 129:36–48

Kimbrell MR, Warshakoon H, Cromer JR, Malladi S, Hood JD, Balakrishna R, Scholdberg TA, David SA (2008) Comparison of the immunostimulatory and proinflammatory activities of candidate gram-positive endotoxins, lipoteichoic acid, peptidoglycan, and lipopeptides, in murine and human cells. Immunol Lett 118:132–141

Jones KJ, Perris AD, Vernallis AB, Worthington T, Lambert PA, Elliott TS (2005) Induction of inflammatory cytokines and nitric oxide in J774.2 cells and murine macrophages by lipoteichoic acid and related cell wall antigens from Staphylococcus epidermidis. J Med Microbiol 54:315–321

Stich AN, DeClue AE (2011) Pathogen associated molecular pattern-induced TNF, IL-1beta, IL-6 and CXCL-8 production from feline whole blood culture. Res Vet Sci 90:59–63

Hessle C, Andersson B, Wold AE (2000) Gram-positive bacteria are potent inducers of monocytic interleukin-12 (IL-12) while gram-negative bacteria preferentially stimulate IL-10 production. Infect Immun 68:3581–3586

Wang JE, Jorgensen PF, Almlof M, Thiemermann C, Foster SJ, Aasen AO, Solberg R (2000) Peptidoglycan and lipoteichoic acid from Staphylococcus aureus induce tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin 6 (IL-6), and IL-10 production in both T cells and monocytes in a human whole blood model. Infect Immun 68:3965–3970

Bjerre A, Brusletto B, Hoiby EA, Kierulf P, Brandtzaeg P (2004) Plasma interferon-gamma and interleukin-10 concentrations in systemic meningococcal disease compared with severe systemic gram-positive septic shock. Crit Care Med 32:433–438

Mandrekar P, Bala S, Catalano D, Kodys K, Szabo G (2009) The opposite effects of acute and chronic alcohol on lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation are linked to IRAK-M in human monocytes. J Immunol 183:1320–1327

Zhao Y, Chen LH (2005) Eicosapentaenoic acid prevents lipopolysaccharide-stimulated DNA binding of activator protein-1 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase activity. J Nutr Biochem 16:78–84

Tang CH, Hsu CJ, Yang WH, Fong YC (2010) Lipoteichoic acid enhances IL-6 production in human synovial fibroblasts via TLR2 receptor, PKCdelta and c-Src dependent pathways. Biochem Pharmacol 79:1648–1657

Kim DS, Han JH, Kwon HJ (2003) NF-kappaB and c-Jun-dependent regulation of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 gene expression in response to lipopolysaccharide in RAW 264.7 cells. Mol Immunol 40:633–643

Albrecht I, Tapmeier T, Zimmermann S, Frey M, Heeg K, Dalpke A (2004) Toll-like receptors differentially induce nucleosome remodelling at the IL-12p40 promoter. EMBO Rep 5:172–177

Blease K, Chen Y, Hellewell PG, Burke-Gaffney A (1999) Lipoteichoic acid inhibits lipopolysaccharide-induced adhesion molecule expression and IL-8 release in human lung microvascular endothelial cells. J Immunol 163:6139–6147

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the British Heart Foundation. It was supported by the NIHR Respiratory Disease Biomedical Research Unit at the Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London. S.K.L. and S.J.F.: British Heart Foundation Clinical Training Fellowships. A.B.-G.: Wellcome Trust University Award.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Finney, S.J., Leaver, S.K., Evans, T.W. et al. Differences in lipopolysaccharide- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cytokine/chemokine expression. Intensive Care Med 38, 324–332 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2444-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-011-2444-5