Abstract

Purpose

To compare the quality of analgesia provided by a remifentanil-based analgesia regime with that provided by a fentanyl-based regime in critically ill patients.

Methods

This was a registered, prospective, two-center, randomized, triple-blind study involving adult medical and surgical patients requiring mechanical ventilation (MV) for more than 24 h. Patients were randomized to either remifentanil infusion or a fentanyl infusion for a maximum of 30 days. Sedation was provided using propofol (and/or midazolam if required).

Results

Primary outcome was the proportion of patients in each group maintaining a target analgesia score at all time points. Secondary outcomes included duration of MV, discharge times, and morbidity. At planned interim analysis (n = 60), 50% of remifentanil patients (n = 28) and 63% of fentanyl patients (n = 32) had maintained target analgesia scores at all time points (p = 0.44). There were no significant differences between the groups with respect to mean duration of ventilation (135 vs. 165 h, p = 0.80), duration of hospital stay, morbidity, or weaning. Interim analysis strongly suggested futility and the trial was stopped.

Conclusions

The use of remifentanil-based analgesia in critically ill patients was not superior regarding the achievement and maintenance of sufficient analgesia compared with fentanyl-based analgesia.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Critically ill patients require analgesia for pain associated with their underlying medical conditions and to facilitate life support technology [1]. Pain assessment in mechanically ventilated patients is independently associated with a reduction in the duration of ventilator support and duration of intensive care unit (ICU) stay [2]. Inadequate analgesia causes serious long-term psychological complications and has several known pathophysiological consequences [3, 4]. On the other hand, excessive analgesia has been associated with nosocomial pneumonia [5], delirium [6], long-term psychological disorders [7], prolonged mechanical ventilation, higher risk of requiring tracheostomy, higher risk of requiring diagnostic imaging to clarify abnormal neurological status [8], and ultimately unnecessarily prolonged ICU and hospital stays [5].

In critically ill patients the pharmacodynamics of opioids are frequently altered by drug interactions and/or hepatic and renal dysfunction [9]. Fentanyl is one of the most widely used opioids in German ICUs for continuous analgesia [1]. It is 80% plasma protein bound, has a high volume of distribution (400 l), has active metabolites, is metabolized by the hepatic cytochrome P450 mixed-function oxidase system (namely CYP3A4), and is predominantly renally eliminated. Consequently its half-life ranges from 3 to 25 h depending on the context (“context-sensitive half-life”) [10].

In contrast remifentanil is rapidly metabolized by non-specific tissue and plasma esterases to a non-potent compound [11]. Consequently its half-life remains at 4 min even after a 4-h infusion (“context-insensitive half-life”). Nevertheless there have been some negative reports regarding remifentanil, specifically in relation to tolerance and hyperalgesia after discontinuation of infusion [12, 13].

Therefore the focus of this study was to investigate a possible difference between the use of fentanyl or remifentanil in achieving an analgesia target [defined with the Behavioral Pain Scale (BPS) or the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)] in critically ill patients.

Methods

Study sites and patients

This is a registered clinical trial (EudraCT number 2005-001907-21). It was performed at two centers (Berlin, Germany and Göppingen, Germany) and patients in this report were recruited between December 2005 and June 2008.

All patients requiring intensive care therapy were considered for enrolment. Additional inclusion criteria were expected ventilation for more than 24 h, ventilation for less than 48 h at the time of enrolment, age 18 years or older, and written informed consent. Exclusion criteria included known allergy to any of the study medications; pregnancy; World Health Organization chronic pain grade 3 or above, i.e., regular use of potent opioids such as morphine, recent opioid analgesia via a spinal catheter, epidural or any other regional technique; American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) classification 5 patients (moribund); participation in a clinical study within the previous 30 days; and neurotrauma or organic brain pathology. The study received final approval from the ethical committee in Berlin and Göppingen (number of ethical approval EA1/125/05).

Study protocol

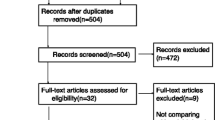

Patients who met enrolment criteria were randomly allocated in a 1:1 ratio to the fentanyl or remifentanil group. The randomization list was created by using computer-based block randomization by a biostatistician with no patient contact. Allocation concealment was ensured by pharmacy-controlled randomization: on the basis of the randomization list, the pharmacies in the respective centers distributed patient-specific syringe pumps and bolus syringes (morphine in the remifentanil group and saline in the fentanyl group) that were identical in size, weight, and appearance. The concentrations were designed so that equal infusion rates were equipotent. All study investigators, staff members, and patients were blinded to the study medication (Fig. 1).

Remifentanil was infused at 0.1–0.4 μg/kg ideal body weight/min and fentanyl at 0.02–0.08 μg/kg ideal body weight/min. The intravenous infusion of both study agents was titrated up to the analgesia target:

-

VAS 4/5 or BPS 7/8: infusion rate of study agent + 0.03 ml/kg/h

-

VAS 5/6 or BPS 8/9: infusion rate of study agent + 0.06 ml/kg/h

-

VAS 7/8 or BPS 9/10: infusion rate of study agent + 0.09 ml/kg/h

-

VAS 9/19 or BPS 10/11: infusion rate of study agent + 0.12 μg/kg/h

The study protocol did not allow any bolus application of either fentanyl or remifentanil. If the patient was awake, we used the VAS and if the patient was sedated we used the BPS. The target scores were a VAS ≤3 and/or a BPS ≤6 at rest. Sedation was delivered by using propofol (to a maximum of 4 mg/kg ideal body weight/h), and midazolam (0.01–0.18 mg/kg ideal body weight/h) could be added if required. Sedation was titrated according to the Richmond Agitation Sedation Scale (RASS). The target RASS was 0 to −1. There were a few exceptions where deeper sedation (up to RASS of −4) was allowed (e.g., patients requiring prone positioning). Unless contraindicated, all patients could receive the following adjuvant analgesics: metamizole (1 g four times daily enterally or intravenously), and/or paracetamol (1 g four times daily enterally or intravenously), and/or clonidine (0.32–1.3 μg/kg/h intravenously). Patients in the remifentanil group received a morphine bolus (0.1 mg/kg) 30 min before ending the study medication. Patients in the fentanyl group received a placebo bolus instead. Rescue pain therapy with morphine boli was allowed at all time points for all patients. Delirium diagnosis was performed by using the Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU (CAM-ICU) in all patients with a RASS > −3 [14].

Sedation was protocolized and patients were assessed on a daily basis for suitability for weaning. Observation time points were as follows: VAS and BPS every hour for the first 6 h, then every 4 h up to 24 h after the start of the study drug and thereafter every 8 h until the end of the study (maximum 30 days).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the proportion of patients in each group obtaining the target analgesia score range (VAS ≤3 and/or a BPS ≤6). Secondary outcome variables were duration of mechanical ventilation, intercurrent complications, and duration of ICU stay and in-hospital stay.

Statistics

The sample size calculation was based on an estimated effect size of 25% (remifentanil superior to fentanyl, based on existing literature and clinical relevance) a type I risk of 5%, a power of 80%, and an expected dropout rate of 15%. The minimum case number was estimated to be 80 per group (160 patients in total) (Fisher’s exact test, nQuery Advisor® Release 6.0, Stat. Solutions Ltd. & South Bank, Crosse’s Green, Cork, Ireland). It was decided a priori to perform an interim analysis after 60 patients in total. Stopping rules for significant efficacy and futility were specified in advance. A successful unblended χ 2 test for the primary endpoint with an adjusted (two-sided) type 1 error of 0.5% at interim analysis was to trigger termination of the study for significant efficacy [15]. Otherwise the independent data monitoring committee (IDMC) was to base its decision on whether to continue the study upon a new sample size calculation after completion of the statistical component of the interim analysis.

For the primary outcome analysis, the exact Fisher test was used to compare the two groups. With respect to the secondary outcome variables, time-to-event data were compared by using the (exact) Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test and event data were compared by using Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests for the secondary outcome variables should be interpreted in a descriptive manner only.

Results

A total of 784 patients were screened for admission (577 in Berlin and 207 in Göppingen). Consent was obtained from 65 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Five patients were excluded following recruitment and so this interim analysis is based on a total of 60 patients (41 from Berlin and 19 from Göppingen). In total 60 patients were analyzed. There were 28 patients in the remifentanil group and 32 patients in the fentanyl group (Fig. 2). In the remifentanil group there were 16 violations to the protocol versus 11 in the fentanyl group (p = 0.34).

The demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of the two groups are shown in Table 1.

Primary outcome measure

Including 100% of the observation time points, there was no significant difference regarding the proportion of patients in each group obtaining the target analgesia score range (50% of 28 remifentanil patients versus 63% of 32 fentanyl patients, p = 0.44). Nor did we find a significant difference between the two groups with respect to maintenance of target analgesia levels for either 90% (75% of 28 remifentanil patients versus 75% of 32 fentanyl patients, p > 0.99) or 80% (82% of 28 remifentanil patients versus 97% of 32 fentanyl patients, p = 0.09) of the time points (Table 2).

At interim analysis we performed a new power calculation based on the fentanyl and remifentanil group proportions that were observed in the first 60 patients (63% of fentanyl patients vs. 50% of remifentanil patients were in the target analgesia score ranges at all time points). On the basis of these new proportions, a type I error of 5% (two-sided), and 80% power, it was calculated that 530 patients (160 had originally been planned) would be required to demonstrate a significant effect. On the basis of this, the IDMC decided in April 2009 that it was extremely unlikely that the trial, should it continue, would reach its objectives and that the required financial and scientific resources could be better utilized elsewhere.

Secondary endpoints

With respect to the secondary endpoints there were no statistically significant differences between the two groups (Table 3).

Administration of additional analgesics and sedatives

RASS values between both groups did not differ significantly during the first 24 h of study inclusion (fentanyl −3.25 vs. remifentanil −4.00, p = 0.68) and during the whole study period (fentanyl −2.25 vs. remifentanil −2.88, p = 0.94). Moreover the median duration of both administered study agents was not significantly different between groups (fentanyl 49.00 h vs. remifentanil 71.00 h, p = 0.13). Furthermore the calculations in Table 4 reveal no statistical significance regarding the duration and the median amount of administered propofol (fentanyl 2.24 mg/kg/h vs. remifentanil 2.14 mg/kg/h, p = 0.66). Even though there was a difference in administered midazolam between both groups (fentanyl 0.09 mg/kg/h vs. remifentanil 0.21 mg/kg/h) this difference did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.36) (Table 4). A conspicuous higher median amount of administered haloperidole in the remifentanil group did not reach statistical significance either (fentanyl 15 mg versus remifentanil 47 mg, p = 0.71).

Discussion

The study results reveal that the use of a remifentanil-based analgesia regime in the critically ill is not superior regarding the achievement and maintenance of sufficient analgesia compared with a fentanyl-based analgesia.

Remifentanil has previously been compared with other opioids in the management of critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation. A meta-analysis by Tan and colleagues identified a total of 11 randomized controlled trials that compared remifentanil with another opioid or hypnotic agent in 1,067 critically ill adult patients. Formal meta-analysis demonstrated no remifentanil-associated benefits with respect to mortality, duration of mechanical ventilation, length of ICU stay, and risk of agitation. Even so, the use of remifentanil was associated with a reduction in the time to extubation after cessation of sedation [16]. However there was significant heterogeneity in the studies grouped for formal meta-analysis. Particularly we do not consider the following four studies in this meta-analysis to be comparable to our study: a randomized controlled trial (RCT) from Belhadj Amor performed on critical care patients who all additionally had renal impairment [17], an RCT from Carrer comparing morphine with morphine plus remifentanil [18], an RCT by Rauf that examined only the first 12 postoperative hours in off-pump cardiac bypass patients [19], and the RCT from Karabinis that included only neurosurgical patients [20].

The seven “comparable” studies included in this review and in our study differ in some important respects. Firstly, whereas previous studies in this field have chosen sedation scores or duration of mechanical variation as the primary outcome variable, we chose validated pain scores. It is well known from previous studies that caregivers underestimate pain in the ICU [4, 21]. Our approach was novel in that we used only validated, patient-determined pain scores. However, all studies in this meta-analysis were based on sedation and, to the best of our knowledge, did not include analgesia-based, validated scoring as target monitoring.

Secondly, in all of the previous positive studies, the control groups were sedated with midazolam. In the negative study [22] and in our study, the control groups were sedated primarily with propofol. The benefit attributed to remifentanil in some of the above studies could have been either a surrogate of the harmful effect of midazolam or dependent upon an interaction between the choice of opioid and midazolam. A recent study reported the harmful effects of lorazepam when compared with dexmedetomidine in a mixed surgical and medical ICU population [23].

Thirdly, we chose fentanyl as the comparator. There are differences across the world regarding choice of opioid for critically ill patients. Fentanyl and sufentanil are the opioids of choice in Germany [1, 24, 25]. In the four studies where the control group received morphine [26–29] the result was significantly in favor of remifentanil. Studies comparing fentanyl and remifentanil have, on the other hand, yielded mixed results [22, 30]. It may be that remifentanil is superior to morphine but not to fentanyl.

Fourthly, our study and three previous studies [22, 26, 30] were performed principally on surgical patients. We note that the studies performed on mixed medical/surgical populations have yielded positive results in favor of remifentanil [27, 28, 31]. Furthermore the mean duration of ventilation in our remifentanil group (5.6 days) was considerably longer than those of the three other studies on surgical patients (14, 13, and 20 h respectively). Intuitively, longer ventilation times in surgical patients reflect higher-risk patients and more complicated postoperative courses. It may be that the beneficial effects of remifentanil are moderate and not as easy to demonstrate in patients with multiple morbidities and complicated postoperative courses.

Patients in the remifentanil group received a 0.1 mg/kg morphine bolus 30 min before the infusion was stopped. The calculations in Table 4 show that the number of administered morphine boli per patient in both groups was only minor [fentanyl 1.00 (0–4.75); remifentanil 1.00 (0–3)] and did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.65). On the basis of this result it is unlikely that the administered morphine boli could have confounded possible benefits of remifentanil and led to a false negative result. The primary reason for using the morphine bolus was reports of rebound hyperalgesia after discontinuation of remifentanil in peri-operative patients [12, 13]. In light of these we felt ethically obliged to include this in our protocol. Dahaba and colleagues [27] took a slightly different approach to this problem. At the start of the weaning process they gave both their study groups a 0.05 mg/kg piritramide bolus (a synthetic opioid with a potency 0.75 times that of morphine and a plasma half-life of 3–12 h). We decided against this design because we were concerned that such a study would not accurately reflect clinical practice. Specifically, in our normal practice we would not routinely give a long-acting opioid after stopping a fentanyl or morphine infusion [4].

As described in the “Methods” section, analgesia and sedation was performed according to a specific protocol in both groups. A protocolized ICU management of sedation and analgesia (including evaluation of sedation, analgesia, and delirium with a therapeutic intervention score) is associated with improved outcome compared with a pre-protocol management. In a study by Skrobik and colleagues [32] the cohort receiving protocolized ICU management had superior analgesia while receiving significantly lower mean doses of opiates. Therefore we cannot exclude that comparing remifentanil and fentanyl in an observational study setting might reveal differences in patients’ outcome.

One major limitation of this study is that this trial was stopped early due to futility. Stopping studies at interim analysis due to futility is controversial [33]. Our protocol stipulated interim analysis at 60 patients and this interim analysis suggested that over 300% more patients than originally planned would be required to demonstrate an effect. Consequently the IDMC recommended stopping. There are compelling ethical reasons to publish interim results [34]. Interim analyses are very relevant to data safety monitoring boards, principal investigators, recruiters, and potential participants of other trials addressing the same question. One further limitation of this study derives from the results that even after the first 24 h of patient enrollment the median RASS values did not match the target RASS (0 to −1). Even though median RASS values as well as median duration of propofol infusion did not differ significantly between groups we cannot exclude that “oversedation” might have masked a possible outcome benefit.

Conclusion

The use of a remifentanil-based analgesia regime in critically ill patients was not superior regarding the achievement and maintenance of sufficient analgesia compared with a fentanyl-based analgesia.

References

Martin J, Parsch A, Franck M, Wernecke KD, Fischer M, Spies C (2005) Practice of sedation and analgesia in German intensive care units: results of a national survey. Crit Care 9:R117–R123

Payen JF, Bosson JL, Chanques G, Mantz J, Labarere J, DOLOREA Investigators (2009) Pain assessment is associated with decreased duration of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: a post hoc analysis of the DOLOREA study. Anesthesiology 111:1308–1316

Jacobi J, Fraser GL, Coursin DB, Riker RR, Fontaine D, Wittbrodt ET, Chalfin DB, Masica MF, Bjerke HS, Coplin WM, Crippen DW, Fuchs BD, Kelleher RM, Marik PE, Nasraway SA, Murray MJ, Peruzzi WT, Lumb PD, Task Force of the American College of Critical Care Medicine (ACCM) of the Society of Critical Care Medicine (SCCM), American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), American College of Chest Physicians (2002) Clinical practice guidelines for the sustained use of sedatives and analgesics in the critically ill adult. Crit Care Med 30:119–141

Martin J, Heymann A, Bäsell K, Baron R, Biniek R, Bürkle H, Dall P, Dictus C, Eggers V, Eichler I, Engelmann L, Garten L, Hartl W, Haase U, Huth R, Kessler P, Kleinschmidt S, Koppert W, Kretz FJ, Laubenthal H, Marggraf G, Meiser A, Neugebauer E, Neuhaus U, Putensen C, Quintel M, Reske A, Roth B, Scholz J, Schröder S, Schreiter D, Schüttler J, Schwarzmann G, Stingele R, Tonner P, Tränkle P, Treede RD, Trupkovic T, Tryba M, Wappler F, Waydhas C, Spies C (2010) Evidence and consensus-based German guidelines for the management of analgesia, sedation and delirium in intensive care—short version. Ger Med Sci 8:Doc02

Rello J, Diaz E, Roque M, Vallés J (1999) Risk factors for developing pneumonia within 48 h of intubation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 159:1742–1746

Pisani MA, Murphy TE, Araujo KL, Slattum P, Van Ness PH, Inouye SK (2009) Benzodiazepine and opioid use and the duration of intensive care unit delirium in an older population. Crit Care Med 37:177–183

Jones C, Griffiths RD, Humphris G, Skirrow PM (2001) Memory, delusions, and the development of acute posttraumatic stress disorder-related symptoms after intensive care. Crit Care Med 29:573–580

Kress JP, Pohlman AS, O’Connor MF, Hall JB (2000) Daily interruption of sedative infusions in critically ill patients undergoing mechanical ventilation. N Engl J Med 342:1471–1477

Devlin JW, Roberts RJ (2009) Pharmacology of commonly used analgesics and sedatives in the ICU: benzodiazepines, propofol, and opioids. Crit Care Clin 25:431–449, vii

Alazia M, Levron JC (1987) Pharmacokinetic study of prolonged infusion of fentanyl in intensive care. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 6:465–466

Egan TD, Minto CF, Hermann DJ, Barr J, Muir KT, Shafer SL (1996) Remifentanil versus alfentanil: comparative pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics in healthy adult male volunteers. Anesthesiology 84:821–833

Guignard B, Bossard AE, Coste C, Sessler DI, Lebrault C, Alfonsi P, Fletcher D, Chauvin M (2000) Acute opioid tolerance: intraoperative remifentanil increases postoperative pain and morphine requirement. Anesthesiology 93:409–417

Calderón E, Pernia A, Ysasi A, Concha E, Torres LM (2002) Acute selective tolerance to remifentanil after prolonged infusion. Rev Esp Anestesiol Reanim 49:421–423

Luetz A, Heymann A, Radtke FM, Chenitir C, Neuhaus U, Nachtigall I, von Dossow V, Marz S, Eggers V, Heinz A, Wernecke KD, Spies CD (2010) Different assessment tools for intensive care unit delirium: which score to use? Crit Care Med 38:409–418

O’Brien PC, Fleming TR (1979) A multiple testing procedure for clinical trials. Biometrics 35:549–556

Tan JA, Ho KM (2009) Use of remifentanil as a sedative agent in critically ill adult patients: a meta-analysis. Anaesthesia 64:1342–1352

Belhadj Amor M, Ouezini R, Lamine K, Barakette M, Labbène I, Ferjani M (2007) Daily interruption of sedation in intensive care unit patients with renal impairment: remifentanil–midazolam compared to fentanyl-midazolam. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 26:1041–1044

Carrer S, Bocchi A, Candini M, Donegà L, Tartari S (2007) Short term analgesia based sedation in the intensive care unit: morphine vs remifentanil + morphine. Minerva Anestesiol 73:327–332

Rauf K, Vohra A, Fernandez-Jimenez P, O’Keeffe N, Forrest M (2005) Remifentanil infusion in association with fentanyl-propofol anaesthesia in patients undergoing cardiac surgery: effects on morphine requirement and postoperative analgesia. Br J Anaesth 95:611–615

Karabinis A, Mandragos K, Stergiopoulos S, Komnos A, Soukup J, Speelberg B, Kirkham AJ (2004) Safety and efficacy of analgesia-based sedation with remifentanil versus standard hypnotic-based regimens in intensive care unit patients with brain injuries: a randomised, controlled trial [ISRCTN50308308]. Crit Care 8:R268–R280

Whipple JK, Lewis KS, Quebbeman EJ, Wolff M, Gottlieb MS, Medicus-Bringa M, Hartnett KR, Graf M, Ausman RK (1995) Analysis of pain management in critically ill patients. Pharmacotherapy 15:592–599

Muellejans B, López A, Cross MH, Bonome C, Morrison L, Kirkham AJ (2004) Remifentanil versus fentanyl for analgesia based sedation to provide patient comfort in the intensive care unit: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial [ISRCTN43755713]. Crit Care 8:R1–R11

Pandharipande PP, Pun BT, Herr DL, Maze M, Girard TD, Miller RR, Shintani AK, Thompson JL, Jackson JC, Deppen SA, Stiles RA, Dittus RS, Bernard GR, Ely EW (2007) Effect of sedation with dexmedetomidine vs lorazepam on acute brain dysfunction in mechanically ventilated patients: the MENDS randomized controlled trial. JAMA 298:2644–2653

Mehta S, Burry L, Fischer S, Martinez-Motta JC, Hallett D, Bowman D, Wong C, Meade MO, Stewart TE, Cook DJ, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group (2006) Canadian survey of the use of sedatives, analgesics, and neuromuscular blocking agents in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med 34:374–380

Soliman HM, Mélot C, Vincent JL (2001) Sedative and analgesic practice in the intensive care unit: the results of a European survey. Br J Anaesth 87:186–192

Dahaba AA, Grabner T, Rehak PH, List WF, Metzler H (2004) Remifentanil versus morphine analgesia and sedation for mechanically ventilated critically ill patients: a randomized double blind study. Anesthesiology 101:640–646

Chinachoti T, Kessler P, Kirkham A, Werawatganon T (2002) Remifentanil vs morphine for patients in intensive care unit who need short-term mechanical ventilation. J Med Assoc Thai 85(Suppl 3):S848–S857

Rozendaal FW, Spronk PE, Snellen FF, Schoen A, van Zanten AR, Foudraine NA, Mulder PG, Bakker J, UltiSAFE investigators (2009) Remifentanil-propofol analgo-sedation shortens duration of ventilation and length of ICU stay compared to a conventional regimen: a centre randomised, cross-over, open-label study in the Netherlands. Intensive Care Med 35:291–298

Breen D, Karabinis A, Malbrain M, Morais R, Albrecht S, Jarnvig IL, Parkinson P, Kirkham AJ (2005) Decreased duration of mechanical ventilation when comparing analgesia-based sedation using remifentanil with standard hypnotic-based sedation for up to 10 days in intensive care unit patients: a randomised trial [ISRCTN47583497]. Crit Care 9:R200–R210

Muellejans B, Matthey T, Scholpp J, Schill M (2006) Sedation in the intensive care unit with remifentanil/propofol versus midazolam/fentanyl: a randomised, open-label, pharmacoeconomic trial. Crit Care 10:R91

Baillard C, Cohen Y, Le Toumelin P, Karoubi P, Hoang P, Ait Kaci F, Cupa M, Fosse JP (2005) Remifentanil–midazolam compared to sufentanil–midazolam for ICU long-term sedation. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 24:480–486

Skrobik Y, Ahern S, Leblanc M, Marquis F, Awissi DK, Kavanagh BP (2010) Protocolized intensive care unit management of analgesia, sedation, and delirium improves analgesia and subsyndromal delirium rates. Anesth Analg 111:451–463

Schoenfeld DA (2005) Pro/con clinical debate: it is acceptable to stop large multicentre randomized controlled trials at interim analysis for futility. Pro: futility stopping can speed up the development of effective treatments. Crit Care 9:34–36 (discussion 34-6)

Bird SM (2001) Monitoring clinical trials. Dissemination of decisions on interim analyses needs wider debate. BMJ 323:1424

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Oliver Betz, Hendrik Marius Mende, Dr. Klaus Kohlhammer, and Doris Endele from the Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care Medicine and Pain Therapy and Anton Plangger, Pharmacy Department, Hospital am Eichert, Eicherstraße 3, 73035 Göppingen, Germany. We would also like to express our gratitude to Sabine Reichelt, Beatrix Laetsch, Esther Maahs, Dr. Heike Wendt (née Marquardt) from the Department of Anesthesiology and Intensive Care Medicine, and Dr. Rybka-Golm from the Pharmacy Department of the Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Campus Virchow Klinikum and Campus Charité Mitte, Berlin, Germany. We are indebted to Professor Ralf Kuhlen (formerly of University Hospital Aachen), and Professor Michael Quintel (University Hospital Göttingen) for their discussion of the preliminary study design and to the members of the IDMC for their time and skills (Professor Gernot Marx of University Hospital Aachen, Professor Andreas Hoeft of University Hospital Bonn, Professor Christian Waydhas of University Hospital Essen, and Professor Ludwig A. Hothorn of the Institute for Biostatistics, Hannover). This study was fully supported by GlaxoSmithKline GmbH & Co.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Spies, C., MacGuill, M., Heymann, A. et al. A prospective, randomized, double-blind, multicenter study comparing remifentanil with fentanyl in mechanically ventilated patients. Intensive Care Med 37, 469–476 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-010-2100-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-010-2100-5