Abstract

Purpose

Subjective and objective social isolation are important factors contributing to both physical and mental health problems, including premature mortality and depression. This systematic review evaluated the current evidence for the effectiveness of interventions to improve subjective and/or objective social isolation for people with mental health problems. Primary outcomes of interest included loneliness, perceived social support, and objective social isolation.

Methods

Three databases were searched for relevant randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Studies were included if they evaluated interventions for people with mental health problems and had objective and/or subjective social isolation (including loneliness) as their primary outcome, or as one of a number of outcomes with none identified as primary.

Results

In total, 30 RCTs met the review’s inclusion criteria: 15 included subjective social isolation as an outcome and 11 included objective social isolation. The remaining four evaluated both outcomes. There was considerable variability between trials in types of intervention and participants’ characteristics. Significant results were reported in a minority of trials, but methodological limitations, such as small sample size, restricted conclusions from many studies.

Conclusion

The evidence is not yet strong enough to make specific recommendations for practice. Preliminary evidence suggests that promising interventions may include cognitive modification for subjective social isolation, and interventions with mixed strategies and supported socialisation for objective social isolation. We highlight the need for more thorough, theory-driven intervention development and for well-designed and adequately powered RCTs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Subjective social isolation and objective social isolation are conceptually distinct [1] and often only moderately correlated [2]. The terms loneliness and perceived social support both refer to people’s subjective perception of their social world (i.e. subjective social isolation) [1, 3]. Loneliness is defined as the unpleasant experience that occurs when there is a subjective discrepancy between desired and perceived availability and quality of social interactions [4]. Perceived social support is the self-rated adequacy of the social resources available to a person [5]. Well-established and widely used measures of loneliness are available, such as the UCLA Loneliness Scale [6]. Objective social isolation, meanwhile, involves having little social contact with other people [7] and can be objectively defined based on quantitative measures of social network size or the frequency of social contacts with others [8]. A summary table of commonly used measures of subjective and objective social isolation is provided in Appendix 1.

In a UK survey, approximately one in five of the general population reported being lonely in the preceding 2 weeks [9]. For people with mental health problems, the odds of being lonely were eight times greater than for the general population, and the odds were increased 20-fold for those with two or three diagnoses (e.g. depression and schizophrenia), compared to those without any diagnosis [10]. Objective social isolation, including having fewer friends [11] and being less likely to date [12], is also more common among people with mental health problems than in the general population. Loneliness has adverse health effects, such as an impaired immune system [13], elevated blood pressure [14], depression [15], and cognitive decline [16]. Moreover, loneliness is associated with poorer quality of life [17] and personal recovery [18], and with more severe mental health symptoms [19]. Similarly, a number of negative health outcomes have been found to be associated with objective social isolation, for example, increased all-cause mortality rate [20], poor physical health outcomes [21, 22], worse psychotic symptoms [23, 24], depressive symptoms [24], and higher risk of dementia [25]. Conversely, social support that is perceived as sufficient is associated with less severe psychiatric symptoms, higher functioning, better personal recovery, greater self-esteem and empowerment, and improved quality of life [26]. These associations between subjective and objective social isolation and poorer outcomes [27,28,29,30] make interventions designed to alleviate social isolation of high interest. Subjective social isolation has recently been increasingly recognised as a treatment priority for people with serious mental illness [31]. By targeting both subjective and objective social isolation as main outcomes in the current review, we aimed to establish the extent of the current evidence base for interventions for each of these potential treatment targets and to understand the similarities or differences between the characteristics of interventions that work for subjective and for objective social isolation.

Some authors have previously systematically reviewed interventions for subjective social isolation [30, 32,33,34,35] and objective social isolation [36,37,38] (Appendix 2). The most recent systematic review focused on subjective social isolation among people with mental health problems was published in 2005 [35]. Three more recent systematic reviews focused on aspects of objective social isolation: one reviewed interventions to increase network size in psychosis [37] and the other two examined interventions targeting social participation in people with mental health problems [36, 38]. Thus, there is no up-to-date systematic review of evidence for a full range of interventions to alleviate subjective and/or objective social isolation among people with a mental health diagnosis.

Masi’s meta-analysis in 2011 [34] has been considered one of the most comprehensive reviews to date examining interventions for loneliness, identifying four main types of intervention. However, Masi’s review included only 20 RCTs and included all populations, not only people with mental health problems. Thus, our paper adds to knowledge from Masi’s review by providing an up-to-date synthesis of interventions for loneliness in people with mental health problems, using a typology of interventions targeting loneliness and related constructs recently developed by Mann and her team [39]. This typology distinguishes among the following: (1) interventions involving changing maladaptive cognitions about others (e.g. cognitive-behavioural therapy or reframing); (2) social skills training and psychoeducation programmes (e.g. family psychoeducation therapy); (3) supported socialisation (e.g. peer support groups, social recreation groups); and (4) wider community approaches (e.g. social prescribing and asset-based community development approaches). These community approaches maximise individuals’ engagement with social resources and/or aim to develop social resources at the level of whole communities.

Methods

We conducted the current systematic review to evaluate the evidence for the effectiveness of interventions designed to alleviate subjective social isolation (including loneliness and perceived social support) and/or objective social isolation among people with mental health problems.

Inclusion criteria

Types of study

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included, with no restrictions on publication dates, the country of origin or language.

Participants

People primarily diagnosed with mental health conditions were included, including depression, anxiety, post-traumatic disorder, psychosis/schizophrenia or bipolar disorders. Any method of identifying or diagnosing people as mentally ill was acceptable. There was no restriction on the age of the participants. However, studies where the samples were people with a primary diagnosis of intellectual disability, autistic spectrum disorders, dementia, any other organic illnesses, substance misuse or physical health problems were excluded, even if some had comorbid mental health diagnoses.

Interventions

This review included interventions which were designed to alleviate subjective or/and objective social isolation for people with mental health problems. Papers were included if subjective or objective social isolation was a primary outcome and excluded if they were secondary outcomes, with another clearly specified primary outcome. Trials were also included if a clear distinction was not made between primary and secondary outcomes, with subjective and/or objective social isolation as one of a number of main outcomes.

Comparison

We included trials where the control group received treatment-as-usual, however defined, no treatment or a waiting-list control. We also included trials which compared different active treatment groups.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were subjective social isolation (including loneliness and perceived social support) and objective social isolation. End-of-treatment outcomes, medium-term outcomes (i.e. up to one year beyond the end-of-treatment time point) and longer-term follow-up outcomes (i.e. more than one year beyond the end-of-treatment time point) were reported separately. The following secondary outcomes were also examined: health status, quality of life, and service use.

Search strategy

Three databases were systematically searched for relevant literature: Medline, Web of Science and PsycINFO. Three groups of search terms were combined: (1) subjective and objective social isolation (e.g. loneliness); (2) mental disorders (e.g. psychosis, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder) and (3) trials (e.g. RCT). For detailed search terms, please see Appendix 3. Reference lists from included studies, relevant systematic reviews, and meta-analyses were hand-searched. Grey literature was searched through OpenGrey by using keywords ‘loneliness’, ‘perceived social support’ and ‘social isolation’.

Data extraction

RM and FM reviewed all titles and abstracts, AA screened half of the papers we retrieved, and final decisions regarding whether a paper should be included or not were made by all three independent reviewers. The primary reviewer (RM) reviewed all full-text papers retrieved, and inter-rater reliability was also evaluated as good between reviewers during the screening process. The final list of included papers was confirmed only when RM, FM, and AA agreed on all papers. Any differences were resolved in consultation with a further independent reviewer (SJ). Data were extracted by RM and FM by using a standardised form developed for the review, including items related to publication year and country, study design, experimental settings, participants, the nature of the intervention, follow-up details, primary and secondary outcomes, any exclusions of participants, and the reasons for these, confounders, and risk of bias.

Quality assessment

The Cochrane Risk of Bias tool [40] was used for the quality assessment. Each included paper was assessed by two reviewers (RM and FM/JT) regarding the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. For each paper, a final decision for each domain was made only if both assessors agreed. If there was disagreement, a third independent assessor (SJ) was consulted.

Synthesis plan

A narrative synthesis was conducted for this systematic review based on the principles from the ESRC’s Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews [41]. The included trials were grouped into three categories: (1) trials that included subjective social isolation as an outcome (primary or one of several, with none specified as primary); (2) trials that included objective social isolation as an outcome; and (3) trials that included both outcomes. Due to the expected heterogeneity in samples and intervention types from this broad review, meta-analysis was judged to be inappropriate.

Results

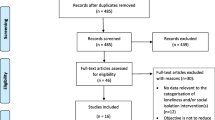

The initial literature search retrieved 5220 papers in total, of which 30 were found to be eligible for inclusion. The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) shows details of the screening process.

The 30 trials involved 3080 participants in total, with individual trial sample sizes ranging from 21 to 357. Nineteen trials had fewer than 100 participants. The median number was 88, and the interquartile range (IQR) was 104. Authors from nine trials specified sample size calculations. The search was conducted in July 2017 and all trials were published between 1976 and 2016. Thirteen trials were conducted in the US, 11 in Europe, 3 in Israel, 2 in China, and 1 in Canada. Thirteen interventions were conducted individually, nine interventions were delivered in groups, four involved individual and group support, and four were implemented online. Ten trials compared different active treatments, four of which had no control group. The remaining 20 trials compared intervention groups with a control group: 13 involved treatment-as-usual groups, 5 involved waiting-list controls, and 2 involved no-treatment controls.

Interventions to reduce subjective social isolation

Fifteen trials included subjective social isolation as primary outcome, or as one of several outcomes with none specified as primary (Table 1).

Two trials included only end-of-treatment outcomes [42, 43]. The follow-up period of the other 13 trials ranged from 1 week to 36 months beyond the end of treatment. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and UCLA Loneliness Scale were frequently administered. The measures used in 14 trials have been shown to have good validity and reliability, but one trial [44] did not use a well-established scale. Nine trials involved people with common mental illnesses (e.g. depression), three involved people with severe mental illnesses (e.g. schizophrenia), and three included people with a variety of mental health diagnoses. The majority of the trials had small sample sizes (< 100); only four trials had more than 200 participants. Five trials included a sample size calculation.

Three trials involved online interventions, one trial combined online intervention and telephone support, four trials implemented face-to-face group intervention, five used face-to-face individual therapy, and the remaining two combined both group and individual formats. Interventions in two trials involved supported socialisation, four trials evaluated psychoeducation/social skills training, four had cognition modification elements, and five trials mixed different intervention types. The duration of the interventions ranged from 1 week to 104 weeks, while such information was missing in four trials and one trial involved only a single intervention session (Appendices 4 and 5).

Regarding quality assessment, method of randomisation was mentioned in half of the trials. Information on allocation concealment, missing data, and blinding were not sufficiently described in most trials. For detailed quality assessments, please see Appendix 6.

Of the ten trials that compared an active intervention with a control group [42, 44, 47, 48, 50,51,52, 54,55,56], none of the authors reported a significant between-group difference. In the five trials comparing at least two different active interventions [43, 45, 46, 49, 53], only Silverman and colleagues [43] found significant between-group differences, reporting a greater improvement in perceived social support from friends (measured by MSPSS friend subscale) in an intervention group involving both music therapy and psychoeducation than in other treatment groups (e.g. music alone). However, differences were not found in other outcomes and this trial did not involve a waiting-list or treatment-as-usual control. As most trials had small samples and lacked sample size calculations, clear conclusions cannot be drawn from negative results.

Eleven out of 15 trials included measures of other relevant outcomes [42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52, 53, 55]. Of these 11 trials, positive outcomes were reported by authors of seven trials. Improved depressive symptoms were reported in trials of interventions with mixed strategies with the following participant groups: adults in the community [48], urban high schoolers [45], and women with major depressive disorders [55]. Another mixed intervention had an effect on social avoidance and social phobia among high school students [52]. A diagnostically mixed participant group exhibited improved progress towards personal recovery and personal goals with psychoeducation/social skills training [42], and a mixed sample who received supported socialisation [44] also reported an improvement in quality of life. However, results on some outcomes in some of the trials did not show significant differences: an intervention with positive results for depression did not improve anxiety [48]; a case management service was not associated with any change in quality of life [50]; an online intervention for people with schizophrenia did not lead to any differences in quality of life or symptoms [53].

Interventions to reduce objective social isolation

Eleven trials included objective social isolation as primary outcome, or as one of several outcomes with none identified as primary (Table 2).

Of 11 trials, one trial [67] only included end-of-treatment outcomes. The follow-up period of the other ten trials ranged from 4 weeks to 2 years beyond the end-of-treatment. In eight trials, validated objective social isolation scales were used. In one trial, objective social isolation was measured by summarising the number, frequency, and type of social connections [73], one trial combined both methods [70], and we could not establish the validity of the measure used in another trial because too little detail was provided [71]. Three trials included people with common mental health problems, six trials involved people with severe mental illnesses, and two trials included diagnostically mixed populations. Most trials involved fewer than 100 participants, and only two had more than 200. Three trials included a sample size calculation.

Seven trials were implemented in an individual format, three were group-based interventions, and one involved both group and individual sessions, plus telephone support. Two trials involved a psychoeducation component/social skills training, one included supported socialisation opportunities, the intervention type of another trial was unclear, and the other seven trials involved interventions with multiple components. The duration of the interventions ranged from 12 weeks to 2 years where this was specified, but such information was not given in four trials (Appendices 4 and 5).

A description of the randomisation process was only included in three trials. Allocation concealment detail was described in five trials. Authors of seven trials did not report how they dealt with missing data. For detailed quality assessments, please see Appendix 6.

Of the six trials that compared an active treatment group with a control group [67,68,69, 71, 73, 76], findings of four trials suggested superior outcomes for their intervention groups over their control groups on objective social isolation measures: a psychoeducation programme for adults with schizophrenia [67], a social network intervention for people diagnosed with schizophrenia spectrum disorders [73], a preventive senior centre group for seniors with mild depression [69], and Social Cognition and Interaction Training (SCIT) for patients with various diagnoses [68]. One trial involving social education for people with schizophrenia and one trial involving home assessment teams for people with mood disorders did not lead to any improvements in objective social isolation [71, 76].

Of the five trials that compared different active interventions [70, 72, 74, 75, 77], positive findings were reported in two trials. One trial included systematic desensitisation and social skills training interventions: both were found to be superior to the control group for increasing social contacts in a sample with personality or mood disorders, although there was no between-group difference between the two active treatment groups [75]. Rivera and colleagues [77] reported an increased contact with staff for participants receiving a consumer-provided programme, compared to non-consumer support. However, Solomon and colleagues [70, 74] also compared consumer versus non-consumer provided mental health care in their two studies and found no significant differences between the groups, or compared to a control group, in social network size or clinical outcomes. Stravynski and colleagues examined whether adding a cognitive modification component to social skills training for people with social phobia and/or avoidant personality disorders improved its effectiveness [72], but found no significant difference between groups. Therefore, the overall evidence regarding the effectiveness of consumer-provided intensive case management for objective social isolation is unclear.

Other relevant outcomes were included in 10 out of 11 trials [67, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77]. Of these ten trials, positive findings were reported in four trials: improved mental state was reported by Rivera and his team, who evaluated a supported socialisation intervention for adults with schizophrenia, other psychotic disorders or mood disorders [77]; reduced depression and social avoidance were reported by Stravynski and colleagues, who evaluated a mixture of strategies for people with social phobia and/or avoidant personality disorder [72]. Atkinson and colleagues also reported a greater quality of life when psychoeducation/social skills training was offered to people with schizophrenia [67], and fewer emergency visits were also reported for a cohort of people with schizophrenia and psychotic symptoms receiving psychoeducation/social skills training [71]. However, Solomon and her team found no differences in psychiatric symptoms or service use for participants who received consumer-led case management [70, 74], and no clinical differences were reported by Terzian and colleagues in a social network intervention for people with schizophrenia [73].

Interventions targeting both subjective and objective social isolation

Four trials included both subjective and objective social isolation as outcomes (Table 3).

One trial [86] only included end-of-treatment outcomes. The follow-up period was between 2 weeks and 6 months in the other three trials [87–89]. Measures with established reliability and validity were used in three trials, but the measure in one trial [86] was developed by the team and not clearly described. One trial included people with common mental health problems, two included people with severe mental illness, and one included people with a variety of different mental health diagnoses. Two trials had fewer than 100 participants and only one had more than 200. A sample size calculation was included in one trial.

One trial involved an individual intervention, two trials involved group interventions, and one trial combined individual, group and phone elements. The length of interventions ranged from 3 to 8 months. One trial was of a supported socialisation intervention, two of cognitive modification, and another used a mixture of strategies (Appendices 4 and 5).

Two trials were judged as at low risk of bias for sequence generation, two trials were at low risk for allocation concealment, and only one trial included a strategy for missing data. All trials were at high risk of bias for their blinding process and other sources of bias, but all were at low risk for selective outcome reporting (Appendix 6).

In all four trials, an intervention group was compared to either a waiting-list or a treatment-as-usual control group. Significant between-group differences in subjective social isolation were demonstrated in three out of four trials: a peer support group for adults with psychosis [86], a group-based intervention involving showing humorous movies for adults with schizophrenia [87], and in-home cognitive behavioural therapy for women with major depressive disorders [88]. Of the three trials in which a significant effect on subjective isolation was reported, significant effects on objective social isolation were also reported in two trials [86, 87]. Schene and colleagues [89] did not find any significant between-group differences for either outcome in a diagnostically mixed sample receiving psychiatric day treatment, compared to standard inpatient care.

In terms of other relevant outcomes, reduction in symptoms were reported by authors in three out of four trials: by Schene and colleagues who examined a mixture of strategies for people with a range of diagnoses [89], by Ammerman and his team who evaluated an intervention with a cognitive modification component for women with depression [88], and by Castelein and colleagues, who evaluated a supported socialisation intervention for people with schizophrenia [86]. Castelein and colleagues also reported additional benefits for quality of life.

Overall results

Table 4 summarises the results for each type of intervention for subjective and objective social isolation, including the ones targeting both subjective and objective social isolation.

Of all the trials that included a subjective social isolation measure (i.e. combining 15 trials including only a subjective social isolation measure and the four trials targeting both subjective and objective social isolation—19 trials in total), positive results were reported in two out of the six trials that examined interventions with a cognition modification component, one out of the three trials of supported socialisation, and one out of the four trials of social skills training/psychoeducation programmes. Authors who evaluated mixed intervention strategies found no significant positive results. None of the trials evaluated wider community approaches alone.

Regarding all the trials which included an objective social isolation measure (i.e. 15 trials), findings from one out of the two trials that involved changing cognitions, one out of the two trials that examined social skills training and psychoeducation, three out of the eight trials with a mixed intervention strategy, as well as all trials (i.e. two trials) that provided supported socialisation, suggested improvements in objective social isolation. No included trials for objective social isolation involved wider community approaches alone. Small samples and lack of sample size calculations need to be borne in mind throughout.

In many of the included trials, subjective and/or objective social isolation was one of several outcomes (with no clearly specified primary outcome), and for some trials, strategies to reduce social isolation were part of an often much broader service improvement approach (e.g. [70, 74, 76, 89]). Just six trials [43, 72, 73, 75, 86, 87] had a measure of social isolation as the clearly stated primary outcome. Four out of these six trials included either a waiting-list or a treatment-as-usual control group [73, 75, 86, 87], and findings from all of these indicated a superior effect of their intervention compared to the control condition on the trials’ objective social isolation outcomes. In these trials, one intervention involved mixed strategies for adults with schizophrenia [73]; one involved supported socialisation for adults with schizophrenia/psychosis [86]; one compared two treatment groups (i.e. systematic desensitisation and social skills training) to a waiting-list control in a sample of people with personality disorders or neurosis [75]; and another trial investigated an intervention with a cognitive modification component for adults with schizophrenia [87]. Similar to Marzillier’s trial [75], Stravynski and colleagues [72] also offered cognitive modification and social skills training to a comparable sample. Stravynksi’s trial involved a very small sample and the authors failed to find any additional improvement when a cognitive modification element was added to their social skills training. In one trial of four active conditions without a control group, for people with varied Axis I mental health diagnoses (e.g. depression, bipolar disorders) [43], the authors reported a positive effect of its psychoeducation component over other intervention groups (e.g. music alone), though only on one outcome: perceived social support from friends. In most trials in which subjective or objective social isolation was specifically targeted as the primary outcome, and interventions were tailored accordingly, positive results were reported: this specific focus may be important for intervention effectiveness.

Discussion

With growing interest in tackling subjective and objective social isolation due to the negative health impact of both issues, we conducted the current systematic review to summarise evidence from RCTs for interventions with subjective and/or objective social isolation as main outcome(s) in people with mental health problems. Given the quality and sample size of many included studies, conclusions need to be cautious. The strategies found were extremely diverse. A tendency not to clearly specify primary outcomes in earlier trials meant that some of the trials meeting our criteria were broad socially oriented programmes in which social isolation measures were among a number of outcomes. The great diversity of interventions and low quality of reporting in some trials made meta-analysis inappropriate.

A small number of mainly small trials (in a mixture of populations) provided some evidence that perceived social support may be increased by interventions that involve cognitive modification (e.g. [88]), although there were also some trials, generally with short follow-ups in which an effect was not found (e.g. [46, 47]). Small sample sizes and lack of sample size calculations make it difficult to draw firm conclusions from the negative studies. In terms of psychoeducation/social skills training programmes (e.g. [42, 43]), no clear supporting evidence was found for subjective social isolation, although an evaluation of one educational intervention found positive results on one subscale [43]. Again, the lack of large well-powered trials with clearly focused interventions makes definitive conclusions hard to draw.

There is also evidence supporting some of the interventions targeting objective social isolation (e.g. [67,68,69]). However, studies included a wide range of types of intervention, none of which can be identified as clearly more effective than others. Group-based interventions and interventions involving supported socialisation appeared to have more evidence supporting their effectiveness in reducing objective social isolation than they do for subjective social isolation. All objective social isolation interventions delivered in a group format demonstrated effectiveness, compared to only two out of eight individual-based interventions, though again, lack of power and of clear theory-driven methods for alleviating isolation diminish our confidence in making firm negative conclusions. For people with mental health problems (especially people with psychosis), initiating and maintaining good social relationships can be disrupted by several difficulties, including self-stigma, psychiatric symptoms, and societal discrimination [94]. Therefore, group-based interventions may offer a pathway to initiating social contacts and practising social skills in a relatively safe environment. It is of note that a good quality multicentre trial of peer support groups from the Netherlands, in which the supported socialisation intervention led to increased social contact, did not improve subjective social isolation [8]. The supported socialisation interventions in our review did not have clear effects on subjective social isolation either. It thus seems possible that supported socialisation is more effective in reducing objective than subjective social isolation. There are two possible explanations: first, a lack of social relationships may not be the only factor contributing to subjective social isolation: social cognitions may also play a significant role [95]; second, organised groups may simply not be an effective way to help lonely people initiate meaningful friendships, start intimate relationships, or maintain or improve current relationships. However, most included studies were small and not informed by power calculations, so few definite conclusions can be drawn.

Some (e.g. [68, 69]), but not all (e.g. [70, 72]), interventions with multiple components appeared to have substantial impacts on improving objective social isolation. Solomon and her colleagues [70, 74] failed to find any significant between-group difference in their two trials, which demonstrated comparable effectiveness of consumer-provided and non-consumer provided support in terms of clinical and psychosocial outcomes. However, it must be noted that multi-component interventions often had multiple outcomes and multiple aims extending beyond alleviating social isolation: they met our inclusion criteria because social isolation was among a number of outcomes, with no specified primary outcome. Psychoeducation programmes/social skills training were evaluated in only two trials [67, 71]: only Atkinson found a significant change on their social isolation outcome, so the effectiveness of this type of intervention remains unclear. It is possible that, as suggested by Mann and colleagues [39], social skills training is more suitable for client groups who are preparing to attend wider community groups, or that it works best when combined with other types of interventions (e.g. [68]).

Cognitive modification has not been shown to be effective for objective social isolation: of the two trials using this technique to target objective social isolation [87, 88], significant changes were only observed in one trial [87] with a short follow-up period and a small sample size. In another trial [72], cognitive modification showed no additional benefits when added to social skills training, but the sample was very small and firm conclusions could not be drawn.

We did not find any relevant trial on interventions focusing on the wider community approaches alone, such as the social prescribing and community asset-development approaches described by Mann and her team [39]. It is possible that interventions where the focus is at community-level are difficult to evaluate via individually randomised trials, but such trials are potentially feasible for individual-level approaches such as social prescribing.

Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to provide an overall synthesis of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions for subjective and/or objective social isolation across a range of mental health diagnoses. But it has important limitations. First, we included trials in which subjective and/or objective social isolation was either a primary outcome or one of a list of outcomes with none specified as primary. This means that we have excluded some trials which might offer relevant evidence based on secondary outcomes, and we have included trials where social isolation is one of a list of outcomes, but may not have been clearly the principal target of the intervention. Few of the included trials involved theory-driven interventions for which social isolation was the clear main target. Second, the conclusions we have drawn are limited by the heterogeneity of the intervention types and patient groups, and the low methodological quality of many included trials. Each type of intervention was only evaluated in a small number of trials and the content of programmes varied greatly. Factors such as lack of information on randomisation processes and allocation concealment resulted in high ratings for risk of bias in many of the studies. Many studies were essentially feasibility or pilot trials, with small sample sizes and no underpinning power calculations: thus no clear conclusions could be drawn from either positive or negative results from these studies, including several trials comparing two or more active interventions. As expected, variations between studies regarding interventions, study participants and outcomes measurement methods precluded meta-analysis. Additionally, four trials did not include a well-established outcome measure (e.g. [45, 73]). Last, although there were no restrictions on the language of the included trials and no filter of language was used during the literature search, no eligible trials in other languages were retrieved. Great efforts were made to retrieve all relevant papers, but some trials in other languages may have been missed.

Research implications

Compared with objective social isolation and social support, the concept of loneliness has only recently been subjected to scientific research. This review identified few trials that included loneliness as their main outcome, and none yielded positive results. Recently published pilot trials have established that loneliness is a feasible target for intervention in severe mental illness, either through face-to-face or digital programmes [31, 96]. However, there is still a pressing need to evaluate interventions for loneliness scientifically in large-scale RCTs, given growing enthusiasm for these approaches. We have thus identified an important gap in the literature.

Some trials focusing on objective social isolation and perceived social support were retrieved, but some advances need to be made to develop a substantial body of evidence in this area. First, most trials were vague in articulating a theoretical basis. The development of a clear theory of change is now regarded as an important step in the development of complex health interventions [97, 98]. Developing such theoretical models could helpfully be informed by a richer understanding of experiences of subjective and objective social isolation among people with mental health problems and their views about what may alleviate these. Thus a co-produced approach to intervention development may result in interventions with a more robust theoretical basis and a closer fit to recipients’ needs. Second, greater advances are likely to be made in this area if future trials can specify interventions in greater detail, and if future systematic reviews use clear systems, such as those applied in this review, to categorise interventions. We found that the descriptions of most interventions were typically vague, and most involved several components and delivery methods. Thus the main components of each intervention were often unclear, and exactly which elements contributed to any positive outcomes was difficult to determine. However, this should not limit the development of future interventions with multiple components (e.g. interventions combining cognitive modification with addressing social/environmental barriers to social participation and developing social relationships). Cacioppo and colleagues [99] proposed that loneliness is a multi-dimensional concept, and there is a clear distinction between intimate, relational, and collective loneliness. Thus, as a complex multi-faceted phenomenon, loneliness may well need to be addressed through multiple means.

Computer/mobile technology has become a popular format for the implementation of interventions in the medical field. Online interventions, including online support groups or chatrooms, may potentially be an effective way to provide social support [100]. However, only four trials targeting online interventions were retrieved in the current review and none has shown positive effects. Authors from existing systematic reviews [101, 102] conclude that there is great future potential for the development and utilisation of mobile apps in the mental health field. Meta-analyses have also demonstrated the use of online interventions as an acceptable and practical method to deliver healthcare for people with depression and anxiety [103, 104]. Another systematic review examined the feasibility of web- and phone-based interventions for people with psychosis: authors supported the feasibility of such interventions, and reported a range of positive outcomes in some of the studies included, including improved social connectedness and socialisation [105]. However, only few trials included in this review were RCTs and social isolation was not generally a primary outcome so that studies were not eligible for inclusion in the current review. One pilot trial has also investigated a novel online intervention called HORYZONS for young people with First Episode Psychosis (FEP), and participants became more socially connected after using HORYZONS [106]. Currently, a full trial utilising a single-blind RCT design to evaluate the effectiveness of this intervention over an 18-month follow-up period is taking place for young people with FEP [107]. In another recent feasibility trial [96], authors developed a digital smartphone application (app) named +Connect, which sought to utilise a positive psychology intervention (PPI) for young adults with early psychosis. The programme was found to be effective in reducing loneliness from baseline to 3-month post-intervention follow-up. Programme users also highlighted the benefits in their social lives of positive reinforcement provided by the app. Thus, although digital interventions have been insufficiently tested in substantial RCTs to date, it is feasible to implement such interventions for people with severe mental health problems in order to reduce loneliness, and there is a need for future research to develop and further examine digital interventions on a larger scale. Additionally, the successful implementation of interventions involving positive psychology in the two pilot trials from Lim and her colleagues [31, 96] supports the idea that subjective social isolation is increasingly recognised as a primary treatment outcome for people with psychosis in the mental health field, and future research should also focus on the development and examination of new types of intervention that target loneliness directly for people with mental health problems.

Other forms of intervention that are so far untested but with potential to have effects on loneliness and social isolation include “friends interventions”, which involve patients’ friends in treatment with the aim of strengthening relationships [108] and other interventions aimed at reinvigorating or restoring existing relationships [109]. By focusing on existing social networks, this type of intervention has potential to improve the quality of social relationships already established prior to mental health diagnosis. Beyond the individual level, there is also potential for the development and robust evaluation of the impact on people with mental health problems of interventions on a larger scale, for example, aimed at developing social connections within groups, communities or neighbourhoods, or at maximising the use of existing community assets [39]. Interventions involving wider communities have been seen as crucial in providing social opportunities for people with mental health problems to engage with their local communities and increase their sense of belonging and self-confidence [39]. Indirect interventions targeting upstream factors that contribute to social isolation [110,111,112,113] are potentially effective, such as programmes to improve housing and reduce poverty.

Clinical implications

There is substantial evidence demonstrating the significant impact of objective and subjective social isolation on health. However, lack of empirical evidence on the efficacy of targeted interventions means that we cannot yet make clear recommendations for interventions. As argued in a recent Lancet editorial [114], there is a need for life science funding prioritising under-researched social, behavioural, and environmental determinants of health. Subjective and objective social isolation are among the social determinants of health that have received insufficient attention. Some of the research we report does provide a starting point for further work: in a few studies there is some evidence of effectiveness, while other studies with small samples have at least demonstrated that interventions are feasible and acceptable.

To conclude, based on this systematic review, current evidence does not yet clearly support scaled-up implementation of any types of intervention for subjective or objective social isolation in mental health services. Even though cognitive modification shows some promise for subjective social isolation, and interventions with mixed approaches and supported socialisation have also demonstrated their effectiveness for objective social isolation, quality of these trials limited our confidence in publicising their effectiveness. Therefore, innovation in intervention development and more high-quality research is needed. We also note that there is much innovative and interesting practice in this field that is not currently underpinned by research, especially in the voluntary sector: defining, establishing the theoretical premises for and evaluating existing models may thus be a promising direction.

References

*Studies included in the systematic review

Wang J, Lloyd-Evans B, Giacco D et al (2016) Social isolation in mental health: a conceptual and methodological review. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52:1451–1461

Coyle CE, Dugan E (2012) Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. J Aging Health 24(8):1346–1363

Andersson L (1998) Loneliness research and interventions: a review of the literature. Aging Ment Health 2(4):264–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607869856506

Peplau LA, Perlman D (1982) Theoretical approaches to loneliness. In: Peplau LA, Perlman D (eds) Loneliness: a sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. Wiley, New York, pp 1–134

Thoits PA (2011) Mechanisms linking social ties and support to physical and mental health. J Health Soc Behav 52(2):145–161

Hays RD, DiMatteo MR (1987) A short form measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess 51(1):69–81

Wilson WJ (1987) The truly disadvantaged: the inner city, the underclass, and public policy. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Wenger GC, Davies R, Shahtahmasebi S, Scott A (1996) Social isolation and loneliness in old age: review and model refinement. Ageing Soc 16:333–358. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x00003457

Victor CR, Scambler SJ, Bowling A, Bond J (2005) The prevalence of, and risk factors for, loneliness in later life: a survey of older people in Great Britain. Ageing Soc 25:357–375

Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Dennis MS et al (2013) Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48(1):5–13

Boeing L, Murray V, Pelosi A, McCabe R, Blackwood D, Wrate R (2007) Adolescent-onset psychosis: prevalence, needs and service provision. Br J Psychiatry 190:18–26

Remschmidt HE, Schulz E, Martin M, Warnke A, Trott GE (1994) Childhood-onset schizophrenia: history of the concept and recent studies. Schizophr Bull 20:727–745

Russell DW, Cutrona CE, de la Mora A, Wallace RB (1997) Loneliness and nursing home admission among rural older adults. Psychol Aging 12(4):574–589

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Crawford LE et al (2002) Loneliness and health: potential mechanisms. Psychosom Med 64:407–417

Alpass FM, Neville S (2003) Loneliness, health and depression in older males. Aging Ment Health 7:212–216

Holwerda TJ, Beekman AT, Deeg DJ, Stek ML, van Tilburg TG et al (2012) Increased risk of mortality associated with social isolation in older men: only when feeling lonely? Results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). Psychol Med 42:843–853

Bastiaansen D, Koot HM, Ferdinand RF (2005) Determinants of quality of life in children with psychiatric disorders. Qual Life Res 14(6):1599–1612

Pernice-Duca F (2010) Family network support and mental health recovery. J Marital Fam Ther 36(1):13–27

Wang JY, Mann F, Lloyd-Evans B, Ma RM, Johnson S (2018) Association between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 18(1):156. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1736-5

Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB (2010) Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med 7(7):e1000316. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316

National Research Council (2011) Explaining divergent levels of longevity in high-income countries. In: Crimmins EM, Preston SH, Cohen B (eds) Panel on understanding divergent trends in longevity in high-income countries. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK62369/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK62369.pdf on July 2019

Pantell M, Rehkopf D, Jutte D, Syme SL, Balmes J, Adler N (2013) Social isolation: a predictor of mortality comparable to traditional clinical risk factors. Am J Public Health 103(11):2056–2062. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301261

Bratlien U, Øie M, Haug E et al (2014) Environmental factors during adolescence associated with later development of psychotic disorders—a nested case–control study. Psychiatry Res 215(3):579–585

Palumbo C, Volpe U, Matanov A, Priebe S, Giacco D (2015) Social networks of patients with psychosis: a systematic review. BMC Res Notes 8:560

Drolet L et al (2013) Assess the contribution of social factors on cognitive performance in older adults. Inpact 2013: international psychological applications conference and trends, pp 282–284

Goldberg RW, Rollins AL, Lehman AF (2003) Social network correlates among people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J 26(4):393–402

Davidson L, Stayner D (1997) Loss, loneliness, and the desire for love: perspectives on the social lives of people with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Rehabil J 20(3):3–12

Holwerda TJ, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT et al (2014) Feelings of loneliness, but not social isolation, predict dementia onset: results from the Amsterdam Study of the Elderly (AMSTEL). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 85(2):135–142

Goldsmith SK, Pellmar TC, Kleinman AM, Bunney WE (2002) Reducing suicide: a national imperative. National Academy Press, Washington, DC

Findlay RA (2003) Interventions to reduce social isolation amongst older people: where is the evidence? Ageing Soc 23:647–658

Lim MH, Penn DL, Thomas N, Gleeson JFM (2019) Is loneliness a feasible treatment target in psychosis? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01731-9

Cattan M, White M, Bond J, Learmouth A (2005) Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: a systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing Soc 25:41–667. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002594

Dickens AP, Richards SH, Greaves CJ, Campbell JL (2011) Interventions targeting social isolation in older people: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 11:647

Masi CM, Chen H-Y, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT (2011) A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Pyschol Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

Perese EF, Wolf M (2005) Combating loneliness among persons with severe mental illness: social network interventions’ characteristics, effectiveness, and applicability. Issues Ment Health Nurs 26(6):591–609

Newlin M, Webber M, Morris D, Howarth S (2015) Social participation interventions for adults with mental health problems: a review and narrative synthesis. Soc Work Res 39(3):167–180. https://doi.org/10.1093/swr/svv015

Anderson K, Laxhman N, Priebe S (2015) Can mental health interventions change social networks? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 15:297. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-015-0684-

Webber M, Fendt-Newlin M (2017) A review of social participation interventions for people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52:369–380

Mann F, Bone JK, Lloyd-Evans B et al (2017) A life less lonely: the state of the art in interventions to reduce loneliness in people with mental health problems. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52:627–638

Higgins JPT, Green S (2011) Assessing risk of bias in included studies, chapter 8. In: Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Sterne JAC (eds) On behalf of the Cochrane Statistical Methods Group and the Cochrane Bias Methods Group: Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://www.handbook.cochrane.org. Retrieved Oct 2016

Popay J, Roberts H et al (2006) Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: a product from the ESRC Methods Programme. Lancaster University. https://doi.org/10.13140/2.1.1018.4643. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233866356_Guidance_on_the_conduct_of_narrative_synthesis_in_systematic_reviews_A_product_from_the_ESRC_Methods_Programme. Retrieved Oct 2016

*Hasson-Ohayon I, Roe D, Kravetz S (2007) A randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of the illness management and recovery program. Psychiatr Serv 58(11):1461–1466

*Silverman MJ (2014) Effects of a live educational music therapy intervention on acute psychiatric inpatients’ perceived social support and trust in the therapist: a four-group randomized effectiveness study. J Music Ther 51(3):228–249

*Boevink W, Kroon H, van Vugt M, Delespaul P, van Os J (2016) A user-developed, user run recovery programme for people with severe mental illness: a randomised control trial. Psychosis 8(4):287–300

*Eggert LL, Elaine RN, Thompson A et al (1995) Reducing suicide potential among high-risk youth: tests of a school-based prevention program. Suicide Life Threat Behav 25(2):276–296

*Zang Y, Hunt N, Cox T (2014) Adapting narrative exposure therapy for Chinese earthquake survivors: a pilot randomised controlled feasibility study. BMC Psychiatry 14:262. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/14/262

*Zang Y, Hunt N, Cox T (2013) A randomised controlled pilot study: the effectiveness of narrative exposure therapy with adult survivors of the Sichuan earthquake. BMC Psychiatry 13:41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244x-13-41

*Gawrysiak M, Nicholas C, Hopko DR (2009) Behavioral activation for moderately depressed university students: randomized controlled trial. J Couns Psychol 56(3):468–475

*Conoley CW, Garber RA (1985) Effects of reframing and self-control directives on loneliness, depression, and controllability. J Couns Psychol 32:139–142

*Bjorkman T, Hansson L, Sandlund M (2002) Outcome of case management based on the strengths model compared to standard care. A randomised controlled trial. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37(4):147–152

*Mendelson T, Leis JA, Perry DF, Stuart EA, Tandon DS (2013) Impact of a preventive intervention for perinatal depression on mood regulation, social support, and coping. Arch Womens Ment Health 16(3):211–218

*Masia-Warner C, Klein RG, Dent HC et al (2005) School-based intervention for adolescents with social anxiety disorder: results of a controlled study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 33(6):707–722

*Kaplan K, Salzer M, Solomon P, Brusilovskiy E, Cousounis P (2011) Internet peer support for individuals with psychiatric disabilities: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med 72:54–62

*Rotondi AJ, Haas GL, Anderson CM et al (2005) A clinical trial to test the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducational intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families: intervention and 3-month findings. Rehabil Psychol 50(4):325–336

*O’Mahen HA, Richards DA, Woodford J et al (2014) Netmums: a phase II randomized controlled trial of a guided Internet behavioural activation treatment for postpartum depression. Psychol Med 44(8):1675–1689

*Interian A, Kline A, Perlick D et al (2016) Randomized controlled trial of a brief Internet-based intervention for families of Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Rehabil Res Dev 53(5):629–640

Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK et al (1990) Psychometric characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess 55:610–617

De Jong Gierveld J, Van Tilburg T (1991) Manual of the Loneliness Scale. VU University, Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Sociology, Amsterdam

Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE (1980) The Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol 39:472–480

Russell D (1982) The Causal Dimension Scale: a measure of how individuals perceive causes. J Pers Soc Psychol 42:1137–1145

Henderson S, Duncan-Jones P, Byrne DG, Scott R (1980) Measuring social relationships: the Interview Schedule for Social Interaction. Psychol Med 10:723–734

Cohen S, Hoberman HM (1983) Positive events and social supports as buffers of life change stress. J Appl Soc Psychol 13:99–125

Asher SR, Wheeler VA (1985) Children’s loneliness: a comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. J Consult Clin Psychol 53:500–505

Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL (1991) The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 32(6):705–714

Krause N, Markides K (1990) Measuring social support among older adults. Int J Aging Hum Dev 30:37–53

Cutrona CE, Russell D (1987) The provisions of social relationships and adaptation to stress. In: Jones H, Perlman D (eds) Advances in personal relationships, vol 1. JAI Press, Greenwich, pp 37–67

*Atkinson JM, Coia DA, Gilmour HG, Harper JP (1996) The impact of education groups for people with schizophrenia on social functioning and quality of life. Br J Psychiatry 168(2):199–204

*Hasson-Ohayon I, Mashiach-Eizenberg M, Avidan M, Roberts DL, Roe D (2014) Social cognition and interaction training: preliminary results of an RCT in a community setting in Israel. Psychiatr Serv 65:555–558

*Bøen H, Dalgard OS, Johansen R, Nord E (2012) A randomized controlled trial of a senior centre group programme for increasing social support and preventing depression in elderly people living at home in Norway. BMC Geriatr 12:20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-12-20

*Solomon P, Draine J (1995) One year outcomes of a randomized trial of case management. Eval Programme Plan 18(2):117–127

*Aberg-Wistedt A, Cressell T, Lidberg Y, Liljenberg B, Osby U (1995) Two-year outcome of team-based intensive case management for patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv 46(12):1263–1266

*Stravynski A, Marks I, Yule W (1982) Social skills problems in neurotic outpatients. Social skills training with and without cognitive modification. Arch Gen Psychiatry 39(12):1378–1385

*Terzian E, Tognoni G, Bracco R et al (2013) Social network intervention in patients with schizophrenia and marked social withdrawal: a randomized controlled study. Can J Psychiatry 58(11):622–631

*Solomon P, Draine J (1995) The efficacy of a consumer case management team: 2-year outcomes of a randomized trial. J Ment Health Admin 22(2):135–146

*Marzillier J, Lambert C, Kellett J (1976) A controlled evaluation of systematic desensitization and social skills training for socially inadequate psychiatric patients. Behav Res Ther 14:225–238

*Cole MG, Rochon DT, Engelsmann F, Ducic D (1995) The impact of home assessment on depression in the elderly: a clinical trial. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 10(1):19–23

*Rivera J, Sullivan AM, Valenti SS (2007) Adding consumer-providers to intensive case management: does it improve outcome? Psychiatr Serv 58:802–809. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.58.6.802

Dunn M, O’Drischoll C, Dayson D et al (1990) The TAPS project 4: an observational study of the social life of long stay patients. Br J Psychiatry 157:842–848

Birchwood M, Smith J, Cochrane R et al (1990) The Social Functioning Scale: the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry 157:853–859

Korkeila J, Lehtinen V, Bijl R et al (2003) Establishing a set of mental health indicators for Europe. Scand J Public Health 31:451–459

Pattison EM, Difrancisco D, Wood P, Frazier H, Crowder JA (1975) A psychosocial kinship model for family therapy. Am J Psychiatry 132:1246–1251

Swaling J, Ensani S, Lundgren K et al (1990) Social network therapy at a child and youth clinic. J Soc Med 1–2:56–64

Gurland B, Yorkston NJ, Stone AR et al (1972) The structured and scaled interview to assess maladjustment. Arch Gen Psychiatry 27:259–267

Centre for Aging and Human Development (1978) Multi-dimensional functional assessment: the OARS methology, 2nd edn. Centre for Aging and Human Development, Duke University, Durham

Pattison EM (1977) A theoretical–empirical base for social system therapy. In: Foulks EF, Wintrob RN, Westermyer J et al (eds) Current perspectives in cultural psychiatry. Spectrum, New York

*Castelein S, Bruggeman R, van Busschbach JT et al (2008) The effectiveness of peer support groups in psychosis: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand 118(1):64–72

*Gelkopf M, Sigal M, Kramer R (1994) Therapeutic use of humor to improve social support in an institutionalized schizophrenic inpatient community. J Soc Psychol 134(2):175–182

*Ammerman RT, Putnam FM, Altaye M et al (2013) Treatment of depressed mothers in home visiting: impact on psychological distress and social functioning. Child Abuse Neglect 37(8):544–554

*Schene AH, van Wijngaarden B, Poelijoe NW, Gersons BPR (1993) The Utrecht comparative study on psychiatric day treatment and inpatient treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand 87(6):427–436

Bridges KR, Sanderman R, van Sonderen E (2002) An English language version of the Social Support List: preliminary reliability. Psychol Rep 90:1055–1058

Sarason IG, Sarason BR, Shearin EN, Pierce GR (1987) A brief measure of social support: practical and theoretical implications. J Soc Pers Relat 4:497–510

Cohen S, Doyle WJ, Skoner DP, Rabin BS, Gwaltney JM Jr (1997) Social ties and susceptibility to the common cold. JAMA 277:1940–1944

Wijngaarden BV (1987) Social network, social steun, gebeurtenissen vragenlijst. Rijksuniversiteit Utrecht, Utrecht

Daumerie N, Vasseur Bacle S, Giordana JY, Bourdais Mannone C, Caria A, Roelandt JL (2012) Discrimination perceived by people with a diagnosis of schizophrenic disorders. INternational study of DIscrimination and stiGma Outcomes (INDIGO): French results. Encephale 3:224–231

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC (2009) Loneliness. In: Leary MR, Hoyle RH (eds) Handbook of individual differences in social behaviour. Guilford Press, New York, pp 227–239

Lim MH, Gleeson JFM, Rodebaugh TL, Eres R, Long KM, Casey K, Abbott JM, Thomas N, Penn DL (2019) A pilot digital intervention targeting loneliness in young people with psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01681-2

Weiss CH (1995) Nothing as practical as good theory: exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In: Connell JP, Kubisch AC, Schorr LB, Weiss CH (eds) New Approaches to evaluating community initiatives, vol 1. Concepts, methods and contexts. The Aspen Institute, Washington, DC, pp 65–92

De Silva MJ, Breuer E, Lee L, Asher L, Chowdhary N, Lund C, Patel V (2014) Theory of change: a theory-driven approach to enhance the medical research council’s framework for complex interventions. Trials 15:267. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-15-267

Cacioppo S, Grippo AJ, London S, Gossens L, Cacioppo JT (2015) Loneliness: clinical import and interventions. Perspect Psychol Sci 10(2):238–249. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691615570616

Davison KP, Pennebaker JW, Dickerson SS (2000) Who Talks? The social psychology of illness support groups. Am Psychol 55:205–217

Lui JHL, Marcus DK, Barry CT (2017) Evidence-based apps? A review of mental health mobile applications in a psychotherapy context. Prof Psychol Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1037/pro0000122

Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J et al (2013) Smartphones for Smarter Delivery of Mental Health Programs: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res 15(11):e247. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2791 (published online 15 Nov 2013). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3841358/#ref7 (accessed Feb 2018)

Andrews G, Basu A, Cuijpers P, Craske MG, McEvoy P, English CL, Newby JM (2018) Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: an update meta-analysis. J Anxiety Disord 55:70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001

Spek V, Cuijpers P, Nyklícek I, Riper H, Keyzer J, Pop V (2007) Internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy for symptoms of depression and anxiety: a meta-analysis. Psychol Med 3:319–328. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291706008944

Alvarez-Jimenez M, Alcazar-Corcoles MA, Blanch CG, Bendall S, McGorry PD, Gleeson JF (2014) Online, social media and mobile technologies for psychosis treatment: a systematic review on novel user-led interventions. Schizophr Res 16:96–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2014.03.021

Alvarez-Jimenez M et al (2012) On the HORYZON: moderated online social therapy for long-term recovery in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2012.10.009

Alvarez-Jimenez M, Bendall S, Koval P et al (2019) HORYZONS trial: protocol for a randomised controlled trial of a moderated online social therapy to maintain treatment effects from first-episode psychosis services. BMJ Open 9:e024104. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024104

Harrop C, Ellett L, Brand R, Lobban F (2015) Friends interventions in psychosis: a narrative review and call to action. Early Interv Psychiatry 9(4):269–278

Biegel D, Tracy E, Corvo K (1994) Strengthening social networks: intervention strategies for mental health case managers. Health Soc Work 19(3):206–216

Hector-Taylor L, Adams P (1996) State versus trait loneliness in elderly New Zealanders. Psychol Rep 78:1329–1330

Fokkema T, De Jong Gierveld J, Dykstra PA (2012) Cross-national differences in older adult loneliness. J Psychol 146(1–2):201–228

Ross CE, Jang SJ (2000) Neighborhood disorder, fear, and mistrust: the buffering role of social ties with neighbors. Am J Community Psychol 28:401–420

Ackley B, Ladwig G (2010) Nursing diagnosis handbook: an evidence-based guide to planning care, 9th edn. Maryland Heights, Mosby

Lancet Editorial (2018) UK life science research: time to burst the biomedical bubble. Lancet 392:10143. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(18)31609-X/fulltext (accessed 16 Aug 2018)

Russell D, Peplau LA, Ferguson ML (1978) Developing a measure of loneliness. J Pers Assess 42:290–294

de Jong-Gierveld J, Kamphuis F (1985) The development of a Rasch-type loneliness scale. Appl Psychol Meas 9(3):289–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662168500900307

Pattison EM, Pattison ML (1981) Analysis of a schizophrenia psychosocial network. Schizophr Bull 7(1):135–143

Acknowledgements

SJ and BLE are partly supported by the NIHR Mental Health Policy Research Unit the UKRI Loneliness and Social Isolation in Mental Health Cross-Disciplinary Network, the UCLH NIHR Biomedical Research Centre and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) North Thames. FM is a Wellcome Clinical Research Training Fellow.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SJ, BLE and RM conceived the review. SJ and BLE commented on search strategy and review protocol, JW recommended search terms. RM developed the search strategy and created review protocol, conducted the literature search, wrote and co-ordinated the drafts. RM, FM and AA independently contributed to the screening process. RM and FM extracted data. RM, FM and JT independently assessed the methodological quality of each included paper. RM screened reference lists of included studies and relevant systematic reviews and meta-analyses. SJ involved in any disagreement between reviewers in the screening process. SJ, BLE, FM and JW contributed comments to the drafts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors state that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

This article is part of the focused issue ‘Loneliness: contemporary insights on causes, correlates, and consequences’.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Measures and scales for subjective and objective social isolation

Measures | Description | For which populations | |

|---|---|---|---|

Subjective social isolation | The University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale [115] | A unidimensional scale to assess the frequency and intensity of one’s lonely experiences, 20 items | General population (e.g. elderly, lonely students, immigrants) People with mental health problems (e.g. psychiatric inpatients, people with depression) |

UCLS-8 [6] | A short-form of UCLA Loneliness Scale, 8 items | General population (e.g. university students, adolescents, elderly sample) People with mental health problems (e.g. people with depression, mixed sample with various diagnoses) | |

The De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale [116] | A 11-item scale measures the feeling of severe loneliness, contains 5 positive and 6 negative items A short-form contains 6 items of the original De Jong-Gierveld Loneliness Scale (3 items for emotional loneliness and 3 items for social loneliness) | General population (e.g. national survey samples from several countries, elderly Chinese) People with mental health problems (e.g. mixed samples with various diagnoses) | |

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) [57] | A 12-item scale to measure perceived overall amount of social support and support from significant other/friends/family | General population (e.g. Chinese university students, young adults, adults with physical disabilities) People with mental health problems (e.g. people with post-traumatic stress disorder, women with severe depressive symptoms) | |

Objective social isolation | Social Network Index (SNI) [92] | A 12-item scale, measures the number of people one has regular contact with | General population (e.g. women with breast cancer, people with severe traumatic brain injury, African-Americans in urban area) People with mental health problems (e.g. old adults with depressive symptoms, people with post-traumatic stress disorder) |

The Pattison Psychosocial Kinship Inventory (PPKI) [117] | Measures the number of people and relationships one considers as important | General population (e.g. dysfunctional families) People with mental health problems (e.g. adults with schizophrenia, people with psychosis) | |

Measures focus on both domains | Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6) | A revised version, contains 6 items, evaluates the quantity and quality of one’s relationship with family and friends | General population (e.g. community-dwelling elderly, Korean American caregivers) People with mental health problems (e.g. mixed samples with different diagnoses, depressed immigrants) |

Social Network Schedule (SNS) [78] | A 6-item scale, measures both quantitative (i.e. the size of one’s social network, the frequency of social communication and the time one spent on socialisation) and qualitative (i.e. quality and intimacy of one’s social relationships, the intensity of social interactions) aspects of one’s social connections | People with mental health problems (e.g. people with non-organic psychosis, people with intellectual disability) | |

Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Support Scale [64] | A 19-item survey measures dimensions of social support: emotional/informational, tangible, affectionate and positive social interactions | General population (people with heart failure in Hong Kong, mothers with children in treatment) People with mental health problems (e.g. adults with schizophrenia spectrum or affective disorder) | |

Interview Schedule for Social interaction (ISSI) [61] | 50 items, measures the availability and perceived adequacy of attachment and social integration | General population (e.g. patients with rheumatoid arthritis, people from Canberra suburbs) People with mental health problems (e.g. outpatients with schizophrenia, inpatient male offenders) |

Appendix 2: Existing systematic reviews and meta-analyses

Authors (published years) | Published years of included studies | Review method | Included participants | How interventions were categorised | Number of studies | Types of study included |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Subjective social isolation interventions | ||||||

Findlay [30] | 1982–2002 | Systematic review | Older people | (1) Increase social support (2) Psychoeducation/social skills training | 17 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies |

Cattan et al. [32] | 1970–2002 | Systematic review | Older people | (1) Social skills training (2) Provide social support (3) Psychoeducation/social skills training | 30 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies |

Dickens et al. [33] | 1976–2009 | Systematic review | Older people | (1) Increase social opportunities (2) Provide social support (3) Psychoeducation/social skills training (4) Address maladaptive social cognitions | 32 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies |

Masi et al. [34] | 1970–2009 | Meta-analysis | Adults, adolescents and children | (1) Increase social opportunities (2) Provide social support (3) Address maladaptive social cognitions (4) Provide social skill trainings | 50 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies |

Perese and Wolf [35] | Unclear | Narrative synthesis | People with mental health problems | Social network interventions: include support groups, psychosocial clubs, self-help groups, mutual help groups and volunteer groups | 36 | Unclear |

Objective social isolation interventions | ||||||

Newlin et al. [36] | Up to September 2014 | Systematic Review and modified narrative synthesis | People with mental health problems | All types of psychosocial interventions | 16 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies and qualitative studies |

Anderson et al. [37] | 2008–2014 | Systematic review | People with psychosis | All types of social network interventions | 5 | RCTs |

Webber and Fendt-Newlin [38] | 2002–2016 | Narrative synthesis | People with mental health problems | Social participation interventions: include social skills training, supported community engagement, group-based community activities, employment interventions and peer support interventions | 19 | RCTs, non-randomised comparison studies, and qualitative studies |

Appendix 3: Search terms in Medline and PsycINFO

Same terms were used for the search in Web of Science with minor changes.

# | Search term |

|---|---|

1 | loneliness.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

2 | Loneliness.mp. or Loneliness/ |

3 | lonely.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

4 | (social support adj5 (subjective or personal or perceived or quality)).mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

5 | Confiding relationship*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

6 | Social isolation.mp. or Social Isolation/ |

7 | Social network*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

8 | socially isolated.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

9 | 1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 |

10 | Mental Disorders/ |

11 | Alcoholism/or Middle Aged/or Child Behaviour Disorders/or Child/or Adolescent/or Stress Disorders, Post-Traumatic/or Adult/or Depression/or Mental Disorders/or mental health problems.mp. or Substance-Related Disorders/ |

12 | Bipolar Disorder/or Psychotic Disorders/or Aged/or Stress, Psychological/or Middle Aged/or Community Mental Health Services/or Adult/or Mental Disorders/or mental illnesses.mp. or Schizophrenia/ |

13 | mental.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

14 | Psychiatr*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

15 | Schizo*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

16 | Psychosis.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

17 | Depress*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

18 | Suicid*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |

19 | Mania*.mp. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, keyword heading word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier] |