Abstract

Purpose

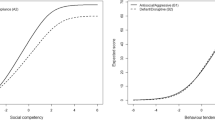

Dimensional approaches are likely to advance understanding of human behaviors and emotions. Nevertheless, it is unclear whether instruments in psychiatry capture variability at the full spectrum of these dimensions. We aimed to investigate this issue for two scales assessing distinct aspects of social functioning: the Social Aptitudes Scale (SAS), a “bidirectional” scale constructed to investigate both “ends” of social functioning; and the social Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL-social), a “unidirectional” scale constructed to assess social problems.

Methods

We investigated 2512 children and adolescents aged 6–14. Item response theory was used to investigate on which range of the trait each scale captures information. We performed quantile regressions to investigate if correlations between SAS and CBCL-social vary within different levels of social aptitudes dimension and multiple logistic regressions to investigate associations with negative and positive clinical outcomes.

Results

SAS was able to provide information on the full range of social aptitudes, whereas CBCL-social provided information on subjects with high levels of social problems. Quantile regressions showed SAS and CBCL-social have higher correlations for subjects with low social aptitudes and non-significant correlations for subjects with high social aptitudes. Multiple logistic regressions showed that SAS was able to provide independent clinical predictions even after adjusting for CBCL-social scores.

Conclusions

Our results provide further validity to SAS and exemplify the potential of “bidirectional” scales to dimensional assessment, allowing a better understanding of variations that occur in the population and providing information for children with typical and atypical development.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Coghill D, Sonuga-Barke EJ (2012) Annual research review: categories versus dimensions in the classification and conceptualisation of child and adolescent mental disorders–implications of recent empirical study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53:469–489

Markon KE, Chmielewski M, Miller CJ (2011) The reliability and validity of discrete and continuous measures of psychopathology: a quantitative review. Psychol Bull 137:856–879. doi:10.1037/a0023678

Salum GA, Sonuga-Barke E, Sergeant J et al (2014) Mechanisms underpinning inattention and hyperactivity: neurocognitive support for ADHD dimensionality. Psychol Med 44:3189–3201. doi:10.1017/S0033291714000919

Shaw P, Malek M, Watson B et al (2012) Development of cortical surface area and gyrification in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry 72:191–197. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.01.031

Lubke GH, Miller PJ (2015) Does nature have joints worth carving? A discussion of taxometrics, model-based clustering and latent variable mixture modeling. Psychol Med 45:705–715. doi:10.1017/S003329171400169X

Rodriguez A, Reise SP, Haviland MG (2015) Applying bifactor statistical indices in the evaluation of psychological measures. J Pers Assess. doi:10.1080/00223891.2015.1089249

Reise SP, Waller NG (2009) Item response theory and clinical measurement. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 5:27–48. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153553

Aggen SH, Neale MC, Kendler KS (2005) DSM criteria for major depression: evaluating symptom patterns using latent-trait item response models. Psychol Med 35:475–487

Swanson JM, Schuck S, Porter MM et al (2012) Categorical and dimensional definitions and evaluations of symptoms of ADHD: history of the SNAP and the SWAN rating scales. Int J Educ Psychol Assess 10:51–70

Greven CU, van der Meer JMJ, Hartman CA et al (2015) Do high and low extremes of ADHD and ASD trait continua represent maladaptive behavioral and cognitive outcomes? A population-based study. J Atten Disord. doi:10.1177/1087054715577136

Greven CU, Merwood A, van der Meer JMJ et al (2016) The opposite end of the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder continuum: genetic and environmental aetiologies of extremely low ADHD traits. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 57:523–531. doi:10.1111/jcpp.12475

Liddle EB, Batty MJ, Goodman R (2009) The Social Aptitudes Scale: an initial validation. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44:508–513. doi:10.1007/s00127-008-0456-4

Soto-Icaza P, Aboitiz F, Billeke P (2015) Development of social skills in children: neural and behavioral evidence for the elaboration of cognitive models. Front Neurosci 9:333. doi:10.3389/fnins.2015.00333

Cordier R, Speyer R, Chen Y-W et al (2015) Evaluating the psychometric quality of social skills measures: a systematic review. PLoS One. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132299

Umberson D, Montez JK (2010) Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav 51:S54–S66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501

Goodman R, Ford T, Richards H et al (2000) The development and well-being assessment: description and initial validation of an integrated assessment of child and adolescent psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 41:645–655

Salum GA, Gadelha A, Pan PM et al (2015) High risk cohort study for psychiatric disorders in childhood: rationale, design, methods and preliminary results. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 24:58–73. doi:10.1002/mpr.1459

Fleitlich-Bilyk B, Goodman R (2004) Prevalence of child and adolescent psychiatric disorders in southeast Brazil. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 43:727–734. doi:10.1097/01.chi.0000120021.14101.ca

Achenbach TM (1991) Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont Burlington, VT

Bordin IAS, Mari JJ, Caeiro MF (1995) Validation of the Brazilian version of the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL): preliminary data. Rev ABP-APAL 17:55–66

Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA (2001) Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles: an integrated system of multi-informant assessment. University of Vermont, Burlington

Pandolfi V, Magyar CI, Dill CA (2012) An initial psychometric evaluation of the CBCL 6-18 in a sample of youth with autism spectrum disorders. Res Autism Spectr Disord 6:96–108. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.009

Rosseel Y (2012) lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. J Stat Softw 48:1–36

Cook KF, Kallen MA, Amtmann D (2009) Having a fit: impact of number of items and distribution of data on traditional criteria for assessing IRT’s unidimensionality assumption. Qual Life Res 18:447–460

Hu L, Bentler PM (1998) Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychol Methods 3:424

McDonald RP (1999) Test theory: a unified approach. Lawrence Erlbaum, Mahwah

Samejima F (1997) Graded response model. In: Van der Linden WJ, Hambleton RK (eds) Handbook of modern item response theory. Springer, New York, pp 85–100

Borsboom D, Rhemtulla M, Cramer AOJ et al (2016) Kinds versus continua: a review of psychometric approaches to uncover the structure of psychiatric constructs. Psychol Med. doi:10.1017/S0033291715001944

Baker FB (2001) The basics of item response theory. ERIC Clearinghouse on Assessment and Evaluation, College Park

Rizopoulos D (2006) ltm: an R package for latent variable modeling and item response theory analyses. J Stat Softw 17:1–25

Koenker R, Bassett Jr G (1978) Regression quantiles. Econ J Econ Soc 46:33–50

Koenker R, Hallock K (2001) Quantile regression: an introduction. J Econ Perspect 15:43–56

Koenker R, Portnoy S, Ng PT, Zeileis A, Grosjean P, Ripley BD (2013) Quantreg: Quantile Regression. R package version 5.05. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/quantreg/index.html. Accessed 26 May 2016

DuPaul GJ, McGoey KE, Eckert TL, VanBrakle J (2001) Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 40:508–515

Parker JG, Asher SR (1987) Peer relations and later personal adjustment: are low-accepted children at risk? Psychol Bull 102:357–389

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric, Arlington

Volkmar FR, McPartland JC (2014) From Kanner to DSM-5: autism as an evolving diagnostic concept. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 10:193–212. doi:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153710

Park LS, Burton CL, Dupuis A et al (2016) The Toronto Obsessive-Compulsive Scale: psychometrics of a dimensional measure of obsessive-compulsive traits. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55(310–318):e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.01.008

Reichenberg A, Cederlöf M, McMillan A et al (2016) Discontinuity in the genetic and environmental causes of the intellectual disability spectrum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:1098–1103. doi:10.1073/pnas.1508093112

Hoffmann MS, Leibenluft E, Stringaris A et al (2016) Positive attributes buffer the negative associations between low intelligence and high psychopathology with educational outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 55:47–53. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2015.10.013

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Axelrud, Dr. DeSousa, Dr. Manfro, Dr. Pan, Dr. Knackfuss, Dr. Mari, Dr. Miguel, and Dr. Salum report no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Rohde has received Honoraria, has been on the speakers’ bureau/advisory board, and/or has acted as a consultant for Eli-Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, and Shire in the last 2 years. He receives authorship royalties from Oxford Press and ArtMed. He also received travel awards for taking part of 2014 APA and 2015 WFADHD meetings from Shire. The ADHD and Juvenile Bipolar Disorder Outpatient Programs chaired by him received unrestricted educational and research support from the following pharmaceutical companies in the last 3 years: Eli-Lilly, Janssen-Cilag, Novartis, and Shire.

Funding

This work was funded through research grants by the Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq, Brazil), the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES, Brazil), the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP, Brazil), and the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul (FAPERGS, Brazil). All of them are public institutions of the Brazilian government developed for scientific research support. Funding sources have no involvement in this study, including no role in data collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Axelrud, L.K., DeSousa, D.A., Manfro, G.G. et al. The Social Aptitudes Scale: looking at both “ends” of the social functioning dimension. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 52, 1031–1040 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1395-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1395-8