Abstract

Objectives

To investigate whether job strain interacts with psychosocial factors outside of the workplace in relation to the risk of major depression and to examine the roles of psychosocial factors outside of the workplace in the relationship between job strain and the risk of major depression.

Methods

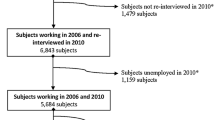

Data from the longitudinal cohort of the Canadian National Population Health Survey (NPHS) were used. Major depressive episode (MDE) in the past 12 months was assessed by the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form. Participants who were working and who were between the ages of 18 and 64 years old in 2000/2001 (n = 6,008) were followed to 2006/2007. MDE that occurred from 1994/1995 to 2000/2001 were excluded from the analysis.

Results

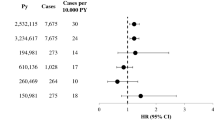

High job strain, negative life events, chronic stress and childhood traumatic events were associated with the increased risk of MDE. There was no evidence that job strain interacted with psychosocial factors outside of the workplace in relation to the risk of MDE. The incidence proportion in participants who reported having exposed to none of the stressors, one type of stressor, two types of stressors and three or more types of stressors was 2.6, 4.3, 6.6 and 14.2%, respectively. The odds of developing MDE in participants who were exposed to three or four types of stressors was more than four times higher than the reference group.

Conclusion

MDE may be facilitated by simultaneous exposure to various stressors. There is a dose–response relationship between the risk of MDE and the number of stressors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kessler RC, Frank RG (1997) The impact of psychiatric disorders on work loss days. Psychol Med 27(4):861–873

Blackmore ER, Stansfeld SA, Weller I, Munce S, Zagorski BM, Stewart DE (2007) Major depressive episodes and work stress: results from a national population survey. Am J Public Health 97(11):2088–2093

Broadhead WE, Blazer DG, George LK, Tse CK (1990) Depression, disability days, and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiologic survey. JAMA 264:2524–2528

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D (2003) Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. JAMA 289:3135–3144

Wang JL, Adair CE, Patten SB (2006) Mental health and related disability among workers: a population-based study. Am J Ind Med 49:514–522

Kawakami N, Araki S, Kawashima M (1990) Effects of job stress on occurrence of major depression in Japanese industry: a case–control study nested in a cohort study. J Occup Med 32:722–725

Wang JL (2004) Perceived work stress and major depressive episode(s) in a population of employed Canadians over 18 years old. J Nerv Ment Dis 192(2):160–163

Wang JL (2005) Work stress as a risk factor for major depressive episode(s). Psychol Med 35(6):865–871

Virtanen M, Honkonen T, Kivimaki M, Ahola K, Vahtera J, Aromaa A, Lönnqvist J (2007) Work stress, mental health and antidepressant medication findings from the Health 2000 Study. J Affect Dis 98:189–197

Plaisier I, de Bruijn JGM, de Graff R, ten Have M, Beekman AT, Penninx BW (2007) The contribution of working conditions and social support to the onset of depressive and anxiety disorders among male and female employees. Soc Sci Med 64:401–410

Netterstrøm B, Conrad N, Bech P, Fink P, Olsen O, Rugulies R, Stansfeld S (2008) The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev 30:118–132

Brown GW, Moran PM (1997) Single mothers, poverty and depression. Psychol Med 27(1):21–33

Blazer DG, Hybels CF (2005) Origins of depression in later life. Psychol Med 35(9):1241–1252

Goldberg D (2006) The aetiology of depression. Psychol Med 36(10):1341–1347

Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Vittum J, Prescott CA, Riley B (2005) The interaction of stressful life events and a serotonin transporter polymorphism in the prediction of episodes of major depression: a replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 62(5):529–535

Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA (2003) Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry 60(8):789–796

Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA (2004) Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol Med 34(8):1475–1482

Kessing LV, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB (2003) Does the impact of major stressful life events on the risk of developing depression change throughout life? Psychol Med 33(7):1177–1184

Libby AM, Orton HD, Novins DK, Beals J, AI-SUPERPFP Team (2005) Childhood physical and sexual abuse and subsequent depressive and anxiety disorders for two American Indian tribes. Psychol Med 35(3):329–340

Patton GC, Coffey C, Posterino M, Carlin JB, Bowes G (2003) Life events and early onset depression: cause or consequence? Psychol Med 33(7):1203–1210

Gillespie NA, Whitfield JB, Williams B, Heath AC, Martin NG (2005) The relationship between stressful life events, the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) genotype and major depression. Psychol Med 35(1):101–111

Chandola T, Kuper H, Singh-Manoux A, Bartley M, Marmot M (2004) The effect of control at home on CHD events in the Whitehall II study: gender differences in psychosocial domestic pathways to social inequalities in CHD. Soc Sci Med 58(8):1501–1509

Niedhammer I, Goldberg M, Leclerc A, Bugel I, David S (1998) Psychosocial factors at work and subsequent depressive symptoms in the Gazel cohort. Scan J Work Environ Health 24(3):197–205

Rugulies R, Bultmann U, Aust B, Burr H (2006) Psychosocial work environment and incidence of severe depressive symptoms: prospective findings from a 5-year follow-up of the Danish work environment cohort study. Am J Epidemiol 163(10):877–887

Stansfeld SA, Fuhrer R, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG (1999) Work characteristics predict psychiatric disorder: prospective results from the Whitehall II Study. Occup Environ Med 56(5):302–307

Statistics Canada (2008) National Population Health Survey Household Component, Cycle 1 to 7 (1994/1995–2006/2007), Longitudinal Documentation. Statistics Canada. Ottawa, Canada. http://www.statcan.gc.ca/imdb-bmdi/document/3225_D5_T1_V4-eng.pdf. Accessed 4 August 2009

Swain L, Catlin G, Beaudet MP (1999) The National Population Health Survey—its longitudinal nature. Health Rep 10:69–82

Kessler RC, Mroczek D (2004) Scoring of the UM-CIDI short forms. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research/Survey Research Center, Ann Arbor (MI)

American Psychiatric Association (1994) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. APA, Washington (DC)

Kessler RC, Mroczek D (2004) An update on the development of mental health screening scales for the US national health interview scales. The University of Michigan Institute for Social Research/Survey Research Center, Ann Arbor (MI)

Karasek RA (1979) Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 24:285–307

Wilkins K, Beaudet MP (1998) Work stress and health. Health Rep 10:47–62

StataCorp (2007) Stata Statistical Software: Release 10.0. Stata Corporation, College Station, TX

Wang JL, Schmitz N, Dewa C (2010) Socioeconomic status and the risk of major depression: The Canadian National Population Health Survey. J Epidemiol Community Health (in press)

Wang J, Keown LA, Patten SB, Williams JA, Currie SR, Beck CA, Maxwell CJ, El-Guebaly NA (2009) A population-based study on ways of dealing with daily stress: comparisons among individuals with mental disorders, with long-term general medical conditions and healthy people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44(8):666–674

Heim C, Bradley B, Mletzko TC, Deveau TC, Musselman DL, Nemeroff CB, Ressler KJ, Binder EB (2009) Effect of childhood trauma on adult depression and neuroendocrine function: sex-specific moderation by CRH receptor 1 gene. Front Behav Neurosci 3:41

Wang JL, Schmitz N, Dewa CS, Stansfeld SA (2009) Changes in perceived job strain and the risk of major depression: results from a population-based longitudinal study. Am J Epidemiol 169(9):1085–1091

Kleinbaum DG, Kupper LL, Morgenstern H (1982) Epidemiologic research: principles and quantitative methods. John Wiley and Sons Inc, Toronto, p 407

Karasek R, Theorell T (1990) A comparison of men’s and women’s jobs. In: Karasek R, Theorell T (eds) Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books, New York, pp 44–45

McDowell I, Newell C (1996) Measuring health: a guide to rating scales and questionnaires, Second edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Acknowledgments

The research and data analysis used data from Statistics Canada. However, the opinions and views expressed do not represent those of Statistics Canada. This study was supported by a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). JianLi Wang holds a CIHR New Investigator award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Schmitz, N. Does job strain interact with psychosocial factors outside of the workplace in relation to the risk of major depression? The Canadian National Population Health Survey. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46, 577–584 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0224-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0224-0