Abstract

Background

Patients who have self-harmed have increased morbidity across a wide range of health outcomes, but there is no evidence on their pattern of health and social service use, and its relationship with repetition of self-harm. Previous studies have shown that resource use and costs in the short-term hospital management of self-harm is associated with certain patient and service characteristics but their impact in the longer term has not been demonstrated. The aim of this study is to test the association between changing levels of costs of health and social care with further episodes of self-harm and to identify the clinical and social factors associated with this.

Method

This was a cost-analysis incidence study of a sample of patients from a cohort of self-harm patients who remained within one region over the course of their follow-up. Resource use was retrospectively observed from their first episode of self-harm (dating back on some occasions to the 1970’s), and costs applied. Panel data analyses were used to identify factors associated with observed costs over time.

Results

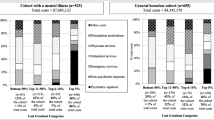

Patients with five or more episodes of self-harm had the highest levels of resource costs. Health and social care costs reduced with time from last episode of self-harm. In the year following the first episode of self-harm, psychiatric care accounted for 69% and psychotropic drug prescriptions 1% of the mean resource costs.

Conclusions

The management of self-harm occurs within a complex system of health and social care. Major self-harm repeaters place the greatest cost burden on the system. Better understanding of the impact of risk assessment models and consequent service provision on clinical outcome may help in the design of effective services for this patient group.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hawton K, Harriss L, Hall S, Simkin S, Bale E, Bond A (2003) Deliberate self-harm in Oxford, 1990–2000: a time of change in patient characteristics. Psychol Med 33:987–995

O’Loughlin S, Sherwood J (2005) A 20-year review of trends in deliberate self-harm in a British town, 1981–2000. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 40:446–453

Platt S, Bille-Brahe U, Kerkhof A, Schmidtke A, Bjerke T, Crepet P et al (1992) Parasuicide in Europe: the WHO/EURO multicentre study on parasuicide. 1. Introduction and preliminary analysis for 1989. Acta Psychiatr Scand 85:97–104

Haw C, Hawton K, Houston K, Townsend E (2001) Psychiatric and personality disorders in deliberate self-harm patients. Br J Psychiatry 178:48–54

Sinclair JMA, Hawton K, Gray A (2009) Six year follow-up of a clinical sample of self-harm patients. J Affect Disord [e-pub ahead of print]

Tyrer P, Alexander J, Ferguson B (1988) Personality assessment schedule (PAS). In: Tyrer P (ed) Personality disorder: diagnosis, management and course. Butterworth/Wright, London, pp 140–167

Beck A, Schuyler D, Herman J (1974) Development of suicidal intent scales. In: Beck A, Resnik H, Lettieri DJ (eds) The prediction of suicide. Charles Press, Maryland

Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, Grant M (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction 88:791–804

Netten A, Curtis L (2005) Unit costs of health and social care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, Canterbury

National Health Service (2005) Annual financial returns of NHS trusts, 2003–2004. National Health Service, Leeds

Department of Health (2005) NHS reference costs 2004. Online access

British National Formulary 50 (2006) http://www.bnf.org/bnf/

StataCorp (2003) Stata Statistical Software: Release 9.0. Stata Corporation, College Station, TX

Byford S, Knapp M, Greenshields J, Ukoumunne OC, Jones V, Thompson S et al (2003) Cost-effectiveness of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate self-harm: a decision-making approach. Psychol Med 33:977–986

Qin P, Mortensen PB, Pedersen CB (2009) Frequent change of residence and risk of attempted and completed suicide among children and adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66:628–632

Suominen KH, Isometsa ET, Ostamo AI, Lonnqvist JK (2002) Health care contacts before and after attempted suicide. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 37:89–94

Oliver MI, Pearson N, Coe N, Gunnell D (2005) Help-seeking behaviour in men and women with common mental health problems: cross-sectional study. Br J Psychiatry 186:297–301

Biddle L, Gunnell D, Sharp D, Donovan JL (2004) Factors influencing help seeking in mentally distressed young adults: a cross-sectional survey. Br J Gen Pract 54:248–253

Sinclair J, Green J (2005) Understanding resolution of deliberate self harm: qualitative interview study of patients’ experiences. Brit Med J 330:1112–1115

Hawton K, Townsend E, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Hazell P, Van Heeringen K, et al (2000) Psychosocial and pharmacological treatments for deliberate self-harm. Cochrane Rev, Library Issue 3, Oxford

Tyrer P, Thompson S, Schmidt U, Jones V, Knapp M, Davidson K et al (2003) Randomized controlled trial of brief cognitive behaviour therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent deliberate-harm: the POPMACT study. Psychol Med 33:969–976

Crawford MJ, Thomas O, Khan N, Kulinskaya E (2007) Psychosocial interventions following self-harm: systematic review of their efficacy in preventing suicide. Br J Psychiatry 190:11–17

ten Have T, Vollebergh W, Bijl RV, de Graaf R (2001) Predictors of incident care service utilisation for mental health problems in the Dutch general population. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 36:141–149

Comtois KA, Russo J, Snowden M, Srebnik D, Ries R, Roy-Byrne P (2003) Factors associated with high use of public mental health services by persons with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatr Serv 54:1149–1154

Crown WH, Finkelstein S, Berndt ER, Ling D, Poret AW, Rush AJ et al (2002) The impact of treatment-resistant depression on health care utilization and costs. J Clin Psychiatry 63:963–971

Byford S, Torgerson D, Raftery J (2000) Economic note—cost of illness studies. Brit Med J 320:1335

Glick HA, Polsky DP, Schulman KA (2001) Trial based economic evaluations: an overview of design and analysis. In: Drummond MF, McGuire A (eds) Economic evaluation in health care: merging theory with practice. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 113–140

Turner RJ, Morgan HG (1979) Patterns of health care in non-fatal deliberate self-harm. Psychol Med 9:487–492

Simon GE, Savarino J, Operskalski B, Wang PS (2006) Suicide risk during antidepressant treatment. Am J Psychiatry 163:41–47

O’Sullivan M, Lawlor M, Corcoran P, Kelleher MJ (1999) The cost of hospital care in the year before and after parasuicide. Crisis 20:178–183

National Institute for Clinical Excellence (2004) The short-term physical and psychological management and secondary prevention of self-harm in primary and secondary care. Report No. 16. National Institute for Clinical Excellence, London

Royal College of Psychiatrists (2004) Assessment following self-harm in adults. Report No. CR122. Royal College of Psychiatrists, London

Bennewith O, Gunnell D, Peters T, Hawton K, House A (2004) Variations in the hospital management of self harm in adults in England: observational study. Brit Med J 328:1108–1109

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the help of Richard Chatwin for his design of the ACCESS data collection database, and all the medical records, primary care and NHS informatics staff who facilitated this research. Julia Sinclair was funded by the Medical Research Council as part of a Health Services Research Training Fellowship. Alastair Gray and Oliver Rivero-Arias were funded by HEFCE and Keith Hawton and Kate Saunders by Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sinclair, J.M.A., Gray, A., Rivero-Arias, O. et al. Healthcare and social services resource use and costs of self-harm patients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 46, 263–271 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0183-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-010-0183-5