Abstract

Objective

To explore whether the 4-item subjective well-being subscale could be used to detect a major depressive illness. Secondly, to describe the prevalence and characteristics of depressed health care attendees at primary healthcare centres.

Method

Using a descriptive, cross-sectional study design, we interviewed 199 consecutive patients about their socio-demographics, subjective well-being (SWB), major depressive illness symptoms and depression severity. The instruments used were translated into Luganda.

Results

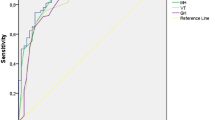

Point prevalence of a current Major Depressive Episode (MDE) was 31.6%. Using a one week reference period, we found that experiencing a lot of distress, having less energy or poor health, having poor emotional and psychological adjustment and not being satisfied with life were significantly more common among patients with a current MDE. The 4-item SWB subscale detected depression of up to 87.1% (95% CI: 0.818–0.923). In logistic regression, all four SWB items predicted a current MDE.

Conclusion

Major depressive illness is a common at primary healthcare level in Uganda. Four simple questions reflecting SWB items have potential to detect diagnosable patients likely to have a current MDE, making general screening procedures less necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Barkow K, Heun R, Ustun TB, Maier W (2001) Identification of items which predict later development of depression in primary health care. Eur Arch Psychiatr Clin Neurosci 251(Suppl 2):II21–26

Klinkman MS (2003) The role of algorithms in the detection and treatment of depression in primary care. J Clin Psychiatr 64(Suppl 2):19–23

Staab JP, Evans DL (2001) A streamlined method for diagnosing common psychiatric disorders in primary care. Clin Cornerstone 3(3):1–9

Valenstein M, Vijan S, Zeber JE, Boehm K, Buttar A (2001) The cost-utility of screening for depression in primary care. Ann Intern Med 134(5):345–360

Coyne JC, Fechner-Bates S, Schwenk TL (1994) Prevalence, nature, and comorbidity of depressive disorders in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatr 16(4):267–276

Liu SI, Prince M, Blizard B, Mann A (2002) The prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and its associated factors in general health care in Taiwan. Psychol Med 32(4):629–637

McQuaid JR, Stein MB, Laffaye C, McCahill ME (1999) Depression in a primary care clinic: the prevalence and impact of an unrecognized disorder. J Affect Disord 55(1):1–10

Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Linzer M, Hahn SR, Williams JB, deGruy FV 3rd, et al. (1995) Health-related quality of life in primary care patients with mental disorders. Results from the PRIME-MD 1000 Study. Jama 274(19):1511–1517

Heggenhougen HK (1995) The world mental health report: current issues in public health. Rapid Science Publishers

Ngoma MC, Prince M, Mann A (2003) Common mental disorders among those attending primary health clinics and traditional healers in urban Tanzania. Br J Psychiatr 183:349–355

Ovuga EBL, Boardman A, Oluka GAO (1999) Traditional healers and mental illness in Uganda. Psychiatric Bull 23:276–279

Kigozi F, Maling S. Mental health in Uganda today. In: Mental health and development: BasicNeeds BasicRights, Charity No. 1079599; 2004 January–March. p. 1–3. Website: http://www. mentalandhealth.org/articl01.pdf

van Praag HM, de Kloet R, van Os J (2004) Stress, the brain and depression. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Musisi S, Tugumisirize J, Kinyanda E, Nkurunziza T (2000) Consultation Liason psychiatry at Mulago hospital. Makerere Med J 35:4–11

Howard KI, Brill PL, Grissom G (2000) COMPASS OP. In: Rush Jr AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, Blacker D, Endicott J, Keith SJ, et al. (eds) Handbook of psychiatric measures. American Psychiatric Association, Washington, DC, pp 207–210

Ott C, Lueger RJ (2002) Patterns of change in mental health status during the first two years of spousal bereavement. Death Stud 26:387–411

Howard KI, Brill P, Lueger RJ, O’Mahoney MT, Grissom GR (1995) Integra outpatient tracking assessment: psychometric properties. Integra, Radnor, PA

American Psychiatric Association (ed) (2000) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th edn. Washington, DC

Bolton P, Wilk CM, Ndogoni L (2004) Assessment of depression prevalence in rural Uganda using symptom and function criteria. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 39(6):442–447

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, et al. (1998) The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatr 59(Suppl 20):22–33, quiz 34–57

Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y. M.I.N.I. Mini international neuropsychiatric interview. English Version 5.0.0/DSM-IV/Current/August 1998

Ndyanabangi S, Basangwa D, Lutakome J, Mubiru C (2004) Uganda mental health country profile. Int Rev Psychiatr 16(1–2):54–62

Lutz W, Rafaeli E, Howard KI, Martinovich Z (2002) Adaptive modelling of progress in outpatient psychotherapy. Psychother Res 14(4):427–443

Howard KI, Orlinsky DE, Lueger RJ (eds) (1995) The design of clinically relevant outcome research: some considerations and an example. Wiley, New York, NY

Pinninti NR, Madison H, Musser E, Rissmiller D (2003) MINI International Neuropsychiatric Schedule: clinical utility and patient acceptance. Eur Psychiatr 18(7):361–364

Rossi A, Alberio R, Porta A, Sandri M, Tansella M, Amaddeo F (2004) The reliability of the mini-international neuropsychiatric interview – Italian version. J Clin Psychopharmacol 24(5):561–563

Kadri N, Agoub M, Gnaoui SE, Alami KH, Hergueta T, Moussaoui D (2005) Moroccan colloquil Arabic version of the MINI international neuropsychiatric interview (MINI): qualitative and quantitative validation. Eur Psychiatr 20(2):193–195

Muller MJ, Szegedi A, Wetzel H, Benkert O (2000) Moderate and severe depression. Gradations for the Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale. J Affect Disord 60(2):137–140

Barkow K, Heun R, Ustun TB, Berger M, Bermejo I, Gaebel W, et al. (2004) Identification of somatic and anxiety symptoms which contribute to the detection of depression in primary health care. Eur Psychiatr 19(5):250–257

Barkow K, Maier W, Ustun TB, Gansicke M, Wittchen HU, Heun R (2003) Risk factors for depression at 12-month follow-up in adult primary health care patients with major depression: an international prospective study. J Affect Disord 76(1–3):157–169

Becker SM (2004) Detection of somatization and depression in primary care in Saudi Arabia. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 39(12):962–966

Katon W, Schulberg H (1992) Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatr 14(4):237–247

Kroenke K (2001) Depression screening is not enough. Ann Intern Med 134(5):418–420

Patten SB, Stuart HL, Russell ML, Maxwell CJ, Arboleda-Florez J (2003) Epidemiology of major depression in a predominantly rural health region. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 38(7):360–365

Preville M, Cote G, Boyer R, Hebert R (2004) Detection of depression and anxiety disorders by home care nurses. Aging Ment Health 8(5):400–409

Staab JP, Datto CJ, Weinrieb RM, Gariti P, Rynn M, Evans DL (2001) Detection and diagnosis of psychiatric disorders in primary medical care settings. Med Clin North Am 85(3):579–596

Sayar K, Kirmayer LJ, Taillefer SS (2003) Predictors of somatic symptoms in depressive disorder. Gen Hosp Psychiatr 25(2):108–114

Yamazaki S, Fukuhara S, Green J (2005) Usefulness of five-item and three-item mental health inventories to screen for depressive symptoms in the general population of Japan. Health Qual Life Outcomes 3:48

The Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care (SBU) (2004) Treatment of depressive disorders. A systematic overview of the literature. Volym 1 Stockholm (in Swedish)

Gureje O, Obikoya B (1992) Somatization in primary care: pattern and correlates in a clinic in Nigeria. Acta Psychiatr Scand 86(3):223–227

Ohaeri JU (2001) Caregiver burden and psychotic patients’ perception of social support in a Nigerian setting. Soc Psychiatr Psychiatr Epidemiol 36(2):86–93

Nease DE, Klinkman MS, Volk RJ (2002) Improved detection of depression in primary care through severity evaluation. J Fam Pract 51(12):1065–1070

Acknowledgements

This work is part of the project titled ‘‘Profiles of Depressive Illness in the Lake Victoria Basin (Uganda)’’, a collaboration between the Department of Psychiatry at Makerere University and the Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Section of Psychiatry at Karolinska Insitutet. We thank Sida/SAREC for funding the project. We also wish to thank interviewers and all study participants for having made this research possible. In a special way, we appreciate the effort of Dr. Stella Neema of Makerere Institute of Social Research (MISR) in the planning of the research study that produced this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

W.W. Muhwezi is a Lecturer and Social Worker, Dept. of Psychiatry and also a Ph.D. student at Makerere University and Karolinska Institute, Dept. of Clinical Neuroscience, Psychiatry-HS, Stockholm, Sweden

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Muhwezi, W.W., Ågren, H. & Musisi, S. Detection of major depression in Ugandan primary health care settings using simple questions from a subjective well-being (SWB) subscale. Soc Psychiat Epidemiol 42, 61–69 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0132-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-006-0132-5