Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Adenosine is an important regulator of metabolism; however, the role of the A1 receptor during ageing and obesity is unclear. The aim of this study was to investigate the effects of A1 signalling in modulating metabolic function during ageing.

Methods

Age-matched young and aged A 1 (also known as Adora1)-knockout (A 1 −/−) and wild-type (A 1 +/+) mice were used. Metabolic regulation was evaluated by body composition, and glucose and insulin tolerance tests. Isolated islets and islet arterioles were used to detect islet endocrine and vascular function. Oxidative stress and inflammation status were measured in metabolic organs and systemically.

Results

Advanced age was associated with both reduced glucose clearance and insulin sensitivity, as well as increased visceral adipose tissue (VAT) in A 1 +/+ compared with A 1 −/− mice. Islet morphology and insulin content were similar between genotypes, but relative changes in in vitro insulin release following glucose stimulation were reduced in aged A 1 +/+ compared with A 1 −/− mice. Islet arteriolar responses to angiotensin II were stronger in aged A 1 +/+ mice, this being associated with increased NADPH oxidase activity. Ageing resulted in multiple changes in A 1 +/+ compared with A 1 −/− mice, including enhanced NADPH oxidase-derived O2 − formation and NADPH oxidase isoform 2 (Nox2) protein expression in pancreas and VAT; elevated levels of circulating insulin, leptin and proinflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12); and accumulation of CD4+ T cells in VAT. This was associated with impaired insulin signalling in VAT from aged A 1 +/+ mice.

Conclusions/interpretation

These studies emphasise that A1 receptors regulate metabolism and islet endocrine and vascular functions during ageing, including via the modulation of oxidative stress and inflammatory responses, among other things.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes is characterised by beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance [1–3] leading to endothelial dysfunction with devastating long-term vascular impairment manifested as numerous complications [4, 5]. The incidence of type 2 diabetes increases with age and obesity, both of which are associated with oxidative stress and chronic inflammation. Mechanistic insights into the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes and novel therapeutic approaches are urgently needed.

Several clinical and epidemiological studies have demonstrated that coffee consumption, mainly caffeine itself, is associated with a reduced risk of developing type 2 diabetes [6–8]. Caffeine inhibits the receptor-mediated actions of adenosine [9], which exerts biological effects via four types of receptors (A1, A2A, A2B and A3) [10]. Adenosine is an important regulator of metabolism; it modulates visceral adipose tissue (VAT) function through A1 receptor-mediated actions in decreasing lipolysis and increasing lipogenesis [11, 12]. Studies utilising gene-modified mice have also suggested that the A1 receptor interacts with insulin and glucagon signalling [13, 14] or secretion [15]. Adenosine was demonstrated to mediate metabolically induced vasodilation in several tissues [16, 17], and we have previously shown that A1 receptor activation modulates in vivo islet blood flow in response to glucose [18].

These results, all obtained in younger animals, indicate that adenosine, via A1 signalling, could affect glucose homeostasis in multiple ways. However, the role of the A1 receptor in age-related metabolic disorders, which is an independent risk factor of type 2 diabetes [19–23], has not been clearly studied. We hypothesised that abrogation of A1 receptor signalling attenuates metabolic dysfunction associated with ageing and obesity, by modulating islet function, oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Indeed, our findings demonstrate this and may have therapeutic implications.

Methods

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Georgetown University, and by equivalent IACUCs in Uppsala and Stockholm, and was performed according to the National Institutes of Health guidelines for the conduct of experiments in animals.

Animals

Experiments were conducted on adenosine A 1 receptor gene (also known as Adora1)-deleted (A 1 −/−) and wild-type mice (A 1 +/+) from heterozygous breeding pairs. The strain was developed by Johansson and co-workers [24] and backcrossed by the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA) to a C57BL/6J background. Both sexes were used, with equal distribution for young (3–5 months) and aged (14–16 months) mice. Mice were housed in temperature-controlled rooms with 12 h light/dark cycles and received a standard rodent chow (4% fat, R36, Lactamin AB, Kimstad, Sweden) and tap water ad libitum.

Food intake and body composition analysis

Food intake was assessed (96 h period) and dual-emission x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) studies were performed using a Lunar PIXImus densitometer (GE Medical-Lunar, Madison, WI, USA) in isoflurane-anaesthetised (Forene; Abbott Scandinavia AB, Solna, Sweden) animals to determine fat and lean masses, as previously described [25].

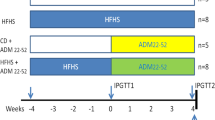

Glucose and insulin tolerance test

Intraperitoneal glucose (IPGTT) and insulin tolerance tests (IPITT) were performed, and the acute effects of pharmacological inhibition of the A1 receptor with 8-cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine (DPCPX), a potent and selective antagonist for the A1 receptor (0.2 mg/kg body weight; Sigma-Aldrich; St Louis, MO, USA) or saline (154 mmol/l NaCl; placebo) were investigated. See Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Methods for further details.

Pancreatic islet arterioles: vascular reactivity studies

Single islets with attached arterioles were dissected and perfused, as previously described [26]. Arteriolar responses to angiotensin II (ANG II; 10−6 to 10−12 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich) alone, or together with apocynin (10−4 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich) were investigated during high (16.7 mmol/l) and low glucose (2.8 mmol/l). Dose–responses to adenosine (10−4 to 10−11 mol/l; Sigma-Aldrich) were also investigated. See ESM Methods for further details.

Pancreatic islets: insulin release and contents

Mouse pancreatic islets were isolated through collagenase digestion and cultured in groups of 150 islets for 3 days. Insulin release was measured in groups of ten islets from each animal after incubation with low (1.67 mmol/l) and high (16.7 mmol/l) glucose. Insulin content in the incubation media and homogenates were determined using a mouse insulin ELISA kit (Mercodia, Uppsala, Sweden) [27].

Lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence of superoxide production

NADPH oxidase-mediated superoxide (O2 −) formation was detected by lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence assay [28]. Pancreas, liver and VAT were separately homogenised and used for subsequent activity measurement. See ESM Methods for further details.

Plasma analysis

Metabolic markers and cytokines were analysed in mouse blood samples using MesoScale Discovery Multi Array Technology (MSD, Rockville, MD, USA). See ESM Methods for further details.

Western blotting

Pancreas, liver and VAT obtained from young and aged mice under basal conditions, after pretreatment with DPCPX (i.p. 0.2 mg/kg body weight) or 15 min after stimulation with insulin (i.p. 0.75 U/kg body weight), with and without DPCPX-pretreatment, were homogenised. Tissue extracts were prepared for SDS-PAGE followed by western blotting of NADPH oxidase isoform 2 (Nox2; BD Biosciences, Stockholm, Sweden), and total and phosphorylated Akt (Ser473; Cell Signaling/BioNordika, Stockholm, Sweden). Protein bands were quantified using densitometry and results are reported as relative optical density of the specific proteins.

Flow cytometric analysis

Mouse tissues were incubated in digestion medium followed by erythrocyte lysis and cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD11b, F4/80, CD86, MHC II, CD3, CD4, CD8α and respective isotype controls. Samples were analysed in a Gallios flow cytometer. See ESM Methods for further details.

Expression of adenosine receptors

mRNA levels of adenosine A 1 , A 2A , A 2B and A 3 receptors in whole pancreas, VAT and isolated pancreatic islets together with islet arterioles were determined by quantitative PCR. See ESM Methods for further details.

Histology and insulin staining

Pancreatic tissue was fixed and processed for evaluation of islet morphology, volume and insulin content. See ESM Methods for further details.

Data analysis

Values are presented as means ± SEM. Single comparisons between normally distributed variables were tested for significance using the Student’s paired or unpaired t test, as appropriate. For multiple group comparisons, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test was used to allow for more than one comparison with the same variable. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Animal characteristics

Body weight was similar in young mice between genotypes. However, aged A 1 −/− had slightly lower body weight than A 1 +/+ mice (Fig. 1a), despite similar daily food intake (Fig. 1b). DEXA analysis revealed an ageing-related lean mass decrease (Fig. 1c, d) and abdominal fat increase (Fig. 1e, f) in A 1 +/+ but not in A 1 −/− mice.

Body composition and food intake. Body weight (a) and food intake (b) were measured and DEXA was used to determine both total lean mass (c), lean mass fraction (d), total abdominal fat (e) and abdominal fat fraction (f) in young and in aged mice. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 20–32/group, except for (b) (n = 16–20/group). *p < 0.05

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests

To investigate the role of A1 receptors in modulating the metabolic phenotype during ageing, we performed glucose and insulin tolerance tests in young and aged mice. There was no difference in basal blood glucose levels or in glucose tolerance between genotypes in young mice (Fig. 2a). However, in aged mice, fasting blood glucose was somewhat higher in A 1 +/+ than in A 1 −/− mice (6.7 ± 0.2 vs 5.9 ± 0.2 mmol/l, p < 0.05), and IPGTT revealed significantly better glucose homeostasis in aged A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 2b, c). The glucose lowering effect of insulin was similar between genotypes at a young age (Fig. 2d). Ageing was associated with reduced insulin sensitivity (Fig. 2e) and increased AUC (Fig. 2f) in A 1 +/+, but not in A 1 −/− mice.

IPGTT and IPITT. Plasma glucose levels were measured in IPGTT (a, b) and IPITT (d, e) in young (a, d; n = 14–18) and aged (b, e; n = 28–32) mice, respectively. The AUC (mmol l−1 min−1) for the 0–120 min period was calculated for both glucose (c) and insulin (f) tolerance tests. To investigate the effects of A1 receptor inhibition, paired crossover measurements were conducted in aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice given saline (placebo) or the A1 receptor antagonist DPCPX 45 min prior to the IPGTT or the IPITT (n = 10–14/group). Inhibition of A1 receptor signalling significantly improved glucose clearance in A 1 +/+ (g), but had no effect in A 1 −/− mice (h). The AUCIPGTT for the 0–120 min period was calculated (i). Inhibition of A1 receptor signalling also improved the insulin response in A 1 +/+ (j), but had no effect in A 1 −/− mice (k). The AUCIPITT for the 0–120 min period was calculated (l). Black triangles, young A 1 +/+; white triangles, young A 1 −/−; black squares, aged A 1 +/+; white squares, aged A 1 −/−; dashed line, DPCPX treatment. Values are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 vs aged-matched A 1 −/− mice, or among the indicated groups for AUC; † p < 0.05 vs young mice of the same genotype; ‡ p < 0.05 between placebo and DPCPX

To validate the effect of A1 receptor inhibition on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity, paired crossover measurements were conducted in aged mice. DPCPX significantly improved both glucose (Fig. 2g) and insulin (Fig. 2j) responses in A 1 +/+ mice compared with placebo. These effects of the A1 antagonist were not observed in A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 2h, k). Corresponding AUCs are shown in Fig. 2i, l.

Metabolic hormones in plasma

Advanced age was associated with elevated levels of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), glucagon, insulin and leptin in A 1 +/+ mice (Fig. 3a–d). However, ageing only induced a small leptin increase in A 1 −/− mice. No significant differences were observed in these hormone concentrations between the genotypes at a young age.

Insulin release and insulin content in isolated islets

To investigate specifically whether A1 receptors modulate insulin release upon glucose challenge, we used isolated islets. High glucose concentrations stimulated insulin release in batch-type incubations in both young and aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice, but this response was attenuated during ageing (Fig. 4a). The relative insulin release response to glucose loading was significantly reduced in aged A 1 +/+ compared with young A 1 +/+ mice and also compared with age-matched A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 4b). This effect could not be explained by differences in total insulin content among the four groups investigated (Fig. 4c). In addition, the islet morphology was similar among groups (ESM Fig. 1). The number of islets was 0.58 ± 0.05 and 0.52 ± 0.07 per mg pancreas in young A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice, and 0.65 ± 0.11 and 0.70 ± 0.12 in aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice (p > 0.05), respectively. Relative islet volume (%) was 1.16 ± 0.08 and 1.24 ± 0.09 in young A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice, and 1.18 ± 0.08 and 1.32 ± 0.13 in aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice (p > 0.05), respectively. There were also no differences in pancreatic weight between young A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice (7.09 ± 0.20 vs 6.85 ± 0.46 mg/g body weight) or between aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice (8.05 ± 0.44 vs 8.02 ± 0.35 mg/g body weight).

Glucose-stimulated insulin release and insulin contents in islets. (a) Insulin release after low glucose (LG; 2.8 mmol/l) and high glucose (HG; 16.7 mmol/l) stimulation in islets. Insulin responses were calculated as percentage change (b), and the total insulin content was analysed (c). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 8/group. *p < 0.05

Isolated and perfused islet arterioles

To examine how the A1 receptor influences the microvasculature, isolated and perfused pancreatic islet arterioles (Fig. 5a) were used for vascular reactivity studies. In aged mice, glucose-induced dilation on afferent arterioles was similar between genotypes, but the subsequent contractile responses to ANG II were significantly attenuated in arterioles from A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 5c). However, in young mice these differences were much less pronounced (Fig. 5b). Simultaneous incubation with apocynin, to inhibit NADPH oxidase activity, attenuated ANG II-mediated contractions in A 1 +/+ mice (25 ± 1% vs 12 ± 3%), but had no effect on arterioles from A 1 −/− mice (13 ± 3% vs 12 ± 1%). With apocynin, the arteriolar responses were similar between A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 5d), suggesting that the difference between genotypes could be related to the regulation of NADPH oxidase function and oxidative stress. There was no difference with regard to the arteriolar diameters among groups (ESM Fig. 2).

Islet arteriolar reactivity. The micrograph shows the experimental set-up (a) with an isolated and perfused islet arteriole (scale bar, 50 μm). (b–d) Changes in luminal diameter of the arteriole were measured in response to high glucose (HG; 16.7 mmol/l) and cumulative doses of ANG II from 1 pmol/l (1 × 10−12) to 1 μmol/l (1 × 10−6) in young mice (b), aged mice (c) and with simultaneous inhibition of NADPH oxidase with apocynin (10−4 mol/l) (d). Black triangles, young A 1 +/+; white triangles, young A 1 −/−; black squares, aged A 1 +/+; white squares, aged A 1 −/−; dashed line, apocynin treatment. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 8/group. *p < 0.05 compared with age-matched A 1 −/− mice; † p < 0.05 compared with arterioles from aged-matched A 1 +/+ mice without simultaneous apocynin treatment (c)

NADPH oxidase-mediated superoxide production and Nox2 level

To investigate further whether oxidative stress contributes to the pathogenesis of age-related metabolic disorders, O2 − formation was measured in pancreas, liver and VAT. Ageing was associated with increased O2 − generation in pancreas (Fig. 6a) and VAT (Fig. 6b) from A 1 +/+ mice. In A 1 −/− mice, this age-dependent change was much less and only occurred in pancreas. In agreement with this, the protein levels of Nox2 in both pancreas (Fig. 6c, e) and VAT (Fig. 6d, f) were significantly increased in A 1 +/+ mice during ageing while no significant changes were observed in A 1 −/− mice. Moreover, the Nox2 level in VAT in aged A 1 +/+ was significantly higher compared with that in A 1 −/− mice. No differences between genotypes were revealed in young mice. NADPH oxidase activity and Nox2 levels in liver were similar between genotypes and did not change with ageing.

Superoxide production and Nox2 level in pancreas and VAT. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide formation in whole pancreas (a) and VAT (b) were measured with lucigenin-dependent chemiluminescence signal (CLU, chemiluminescence unit). Western blot was used to detect Nox2 level in pancreas (c, e) and VAT (d, f). Part (c, d) illustrates two representative samples per group obtained from different gels. Expression levels were normalised to β-actin after densitometric quantification. Values are mean ± SEM, n = 10–16/group. *p < 0.05; † p = 0.08

Cytokines in plasma

Considering the interaction between oxidative stress and inflammation, we measured systemic cytokine levels to investigate if abrogation of A1 receptor signalling also influenced the inflammatory status. Advanced age was associated with elevated circulating TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-10 levels in A 1 +/+ mice, but in aged A 1 −/− mice only IL-10 was elevated (Fig. 7a–e). In agreement with this, the proinflammatory cytokines levels were significantly higher in aged A 1 +/+ mice compared with age-matched A 1 −/− mice. No differences of the cytokines investigated were observed between genotypes in young mice.

Cytokines in plasma. Plasma levels of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12 and IL-10 (a–e) were determined using the MesoScale Discovery assay in young and aged mice. There were no differences of plasma IFN-γ and keratinocyte-derived chemokine/growth-related oncogene (KC/GRO) among groups (data not shown). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 12–16/group. *p < 0.05

Populations of macrophages and T cells in VAT

To further understand the potential role of A1 signalling in regulating inflammation during ageing and metabolic disorder, flow cytometric analysis was performed on single-cell suspensions extracted from VAT (Fig. 8a). There were no significant differences in total macrophage population in either young or aged mice between genotypes (Fig. 8b, d), but the number of CD86+ macrophages was significantly higher in aged A 1 −/− mice compared with age-matched A 1 +/+ mice (Fig. 8c). A 1 +/+ mice showed an age-related enhancement of total T cells and specifically of the CD4+ T cell population, this not being evident in A 1 −/− mice (Fig. 8e, f). There were no differences regarding numbers of macrophages and T cells in the pancreas or liver.

Macrophages and T cell populations in VAT. Part (a) depicts the gating strategy. No significant differences in total macrophages (CD11b+F4/80+) and MHCII+ macrophages (CD11b+MHCII+) were evident between genotypes (b, d). However, CD86+ macrophages (CD11b+CD86+) were significantly higher in aged A 1 −/− mice compared with age-matched A 1 +/+ mice (c). T cell population analysis revealed an age-dependent increase of total T cells (CD3+CD11b+) and CD4+ T cells (CD3+CD4+) in A 1 +/+ mice, but this phenotype was absent in A 1 −/− mice (e, f). No differences were evident in CD8+ T cell populations (CD3+CD8+) between genotypes at different ages (g). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 6/group. *p < 0.05; † p = 0.1

Akt phosphorylation in VAT

To examine if the difference in insulin sensitivity, oxidative stress and immune cell population was manifested in a downstream cellular event, we determined Akt and Akt phosphorylation in VAT from young and aged A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice, and in aged mice 15 min following i.p. injection with insulin (0.75 U/kg body weight) (Fig. 9a–d). There were no differences in basal Akt and p-Akt levels between genotypes (Fig. 9b, c), but ageing was associated with significantly higher p-Akt/Akt ratio in aged A 1 +/+ compared with young A 1 +/+ mice (Fig. 9d). Importantly, insulin-induced phosphorylation of Akt was markedly increased in A 1 −/−, but not significantly changed in age-matched A 1 +/+ mice (Fig. 9d). In another cohort, mice were treated with DPCPX 45 min prior to the insulin challenge. DPCPX alone did not change the expression and phosphorylation levels of Akt. However, acute inhibition of A1 receptor signalling increased p-Akt and p-Akt/Akt ratio following insulin challenge in the A 1 +/+ mice, to the same level as in the A 1 −/− (Fig. 9e–h).

Phosphorylation of Akt in VAT. Parts (a, e) illustrate three representative samples per group obtained from different gels. Expression levels were normalised to β-actin, and results after densitometric quantification are shown for p-Akt (b), total Akt (c) and relative p-Akt-to-Akt levels (d). Acute A1 inhibition with DPCPX, followed by insulin challenge, increased p-Akt and p-Akt/Akt ratio in the A 1 +/+ mice to the same level as in the A 1 −/− mice (e–h). Values are mean ± SEM, n = 6/group. *p < 0.05

Expression of adenosine receptors

To clarify if the different metabolic phenotypes during ageing and between A 1 +/+ and A 1 −/− mice were attributable to the possible differences of adenosine receptors expression, we used quantitative PCR to determine the expression of all four subtypes of adenosine receptors in pancreas (ESM Fig. 3a–d), islets together with their arterioles (ESM Fig. 3e–h) and in VAT (ESM Fig. 3i–l). The A 1 receptor gene expression was undetectable in A 1 −/− mice. In all tissues, no differences in A 2A , A 2B and A 3 receptor expression between genotypes were observed in either young or aged mice. The same adenosine receptor subtypes were also similarly expressed in young and aged mice of the same genotype.

Discussion

Our major finding is that abrogation of A1 signalling improves the metabolic profile during ageing. The underlying mechanisms are multifactorial: besides the known direct actions on lipolysis and lipogenesis [11, 12], we found actions on peripheral insulin signalling, presumably via attenuation of NADPH oxidase function, as well as modulation of inflammatory pathways in VAT apparently being involved. Moreover, direct effects of A1 signalling on the islet microvasculature, and insulin release, are also involved.

We observed an age-dependent reduction in lean mass and an accumulation of VAT in wild-type but not in A 1 −/− mice. This is entirely compatible with previous studies showing that endogenous adenosine, through A1 receptor signalling, reduces lipolysis and enhances lipogenesis [29]. We also found that advanced age was associated with elevated blood glucose levels, impaired glucose tolerance and insulin responses or signalling in A 1 +/+ but not in A 1 −/− mice. Pharmacological inhibition of the A1 receptor improved glucose tolerance in aged wild-type mice, but had no effect in A 1 knockouts. Our data indicate that not only acute intervention of A1 receptors will affect the metabolic function, but that A1 receptors are also participating in the metabolic derangement in mice during ageing. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that A1 receptor signalling influences both VAT and glucose regulation during ageing and emphasise the potential therapeutic value of targeting of A1 receptors in type 2 diabetes.

Adenosine is known to affect the endocrine pancreas per se [30], and previous studies suggested that adenosine receptors can modulate insulin and glucagon secretion [13]. We found advanced age to be associated with an elevation of insulin, glucagon, GLP-1 and leptin in A 1 +/+ mice, but in aged A 1 −/− mice only leptin levels were increased. Thus, the beneficial effect of eliminating A1 receptor signalling was extended to the hormone status. Increased leptin concentration or resistance were suggested as contributing to the inflammatory status in adipose tissue [31] and have been linked to age-associated disorders including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, the metabolic syndrome and diabetes [32–36]. Elevated glucagon levels and insulin resistance are generally thought to contribute to the pathophysiology of hyperglycaemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes.

Our islet studies demonstrated that the absence of A1 receptors does not directly affect islet morphology or insulin content. However, ageing was associated with reduced glucose-stimulated insulin release in wild-type mice, but this age-dependent reduction was not observed in A 1 −/− mice. Islet blood flow is normally coupled to islet insulin release [37, 38]. To provide a better possibility to study only the islet afferent arteriole, we used a recently developed technique with isolated and perfused single islets with attached arterioles [26]. Similar to that recently described for renal afferent arterioles [39], islet arterioles from A 1 −/− mice displayed reduced contractility to ANG II. This was apparent during both normo- and hyperglycaemic conditions, although much more profound during the latter. Since the baseline diameters of the islet arterioles were similar in all the groups, one may speculate that, at physiological ANG II concentrations, aged A 1 +/+ mice would have an increased arteriolar resistance. However, future studies with other techniques are required to confirm this hypothesis.

Oxidative stress, particularly O2 −, has been demonstrated to reduce islet blood flow [40]. ANG II stimulates NADPH oxidase-mediated O2 − formation, which contributes to its pronounced vasoactive properties. Interestingly, reduction of oxidative stress by the NADPH oxidase inhibitor apocynin attenuated ANG II-mediated contraction in A 1 +/+ mice, but had no effect on islet arterioles from A 1 −/− mice. This suggests an important role of the adenosine A1 receptor in modulating O2 − production. This notion has also been described in models of ANG II-induced hypertension in which blood pressure elevation and oxidative stress were markedly attenuated in A 1 gene-deleted mice [39, 41].

Increasing evidence from experimental and clinical studies has demonstrated that oxidative stress and inflammation are key factors that contribute to the progression of metabolic disorders including type 2 diabetes [42, 43]. In the present study we show that ageing is associated with increased NADPH oxidase-derived O2 − formation, together with higher Nox2 levels, in both pancreas and VAT from A 1 +/+ mice. This age-dependent elevation in O2 − formation and oxidative stress was clearly attenuated, or even absent, in gene-deleted animals, which certainly may contribute to their better metabolic phenotype.

Age-related VAT accumulation is associated with a chronic, low-grade inflammation and has been increasingly recognised as an independent risk factor of the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes [44–46]. Almost all immune cell subsets are present in VAT. Their functions are still under discussion, although it is generally accepted that total T cell and macrophage populations are increased and contribute to the meta-inflammation evident in obesity. We did not discern differences in total macrophages among groups, but observed a significant enhancement of the CD86+ macrophage population in aged A 1 −/− mice, indicating elevated antigen presentation capacity. Interestingly, another recent study reported a lipolysis-related macrophage infiltration in adipose tissue without presenting pro-inflammatory characters [47]. As A 1 −/− mice have elevated lipolysis and remain lean, this enhancement of CD86+ macrophages may be due to a response to the continuous release of non-esterified fatty acids. As young mice have much lower lipolysis levels, no differences (e.g. in fat mass) were evident between genotypes at an early age. However, ageing resulted in a significant increase of total T cells and CD4+ T cells in VAT in A 1 +/+ mice, while this was not the case in A 1 −/− mice. In addition, levels of circulating proinflammatory cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12) were increased in aged A 1 +/+ but not in A 1 −/− mice. These findings indicate that a sustained inflammation occurs during ageing and obesity, and may lead to subsequent metabolic disorders, as has been previously suggested [48, 49]. Moreover, accumulation of CD4+ T cells in VAT may be a key contributor to this systemic inflammation and can be modulated via A1 receptor signalling. Further investigations on the immunomodulation effects of the A1 receptor during ageing and the metabolic syndrome are needed and will provide additional insights in developing therapeutic strategies for type 2 diabetes. It seems likely that decreased VAT accumulation and inflammation may contribute to the better metabolic regulation in the A 1 −/− mice during ageing, including better insulin sensitivity. Indeed, our data show significantly better insulin signalling in aged A 1 −/− mice, as demonstrated by increased phosphorylation of Akt kinase in VAT upon insulin stimulation. This insulin signalling pathway was markedly reduced in aged-matched wild-type mice and may contribute to their impaired glucose clearance function.

Besides the A1 receptor, also adenosine receptor A2A and A2B play a role in modulating glucose homeostasis and obesity [50, 51]. We did not reveal any significant differences regarding the A2 and A3 receptor expression among the groups, suggesting no compensatory changes following A 1 receptor deletion. Thus, we believe the improved metabolic phenotypes in the A 1 −/− mice in our study were due to the abrogation of A1 signalling and our findings further suggest a pivotal role of the A1 receptor in modulating especially the function of VAT, which may affect the metabolic homeostasis.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrates an important role of the adenosine A1 receptor in modulating glucose and insulin homeostasis, as well as islet endocrine and arteriolar function, during ageing. Mechanistically, our findings suggest that abrogation of A1 signalling may protect from age-dependent oxidative stress and production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and hence improve insulin release and signalling (Fig. 10). Thus, abrogation of A1 receptor signalling can both have acute effects and give long-term prevention of the development or progression of diabetes. Future studies in humans should be aimed at determining the therapeutic value of modulating A1 signalling.

Abbreviations

- ANG II:

-

Angiotensin II

- DPCPX:

-

8-Cyclopentyl-1,3-dipropylxanthine

- DEXA:

-

Dual-emission x-ray absorptiometry

- GLP-1:

-

Glucagon-like peptide-1

- IPGTT:

-

Intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test

- IPITT:

-

Intraperitoneal insulin tolerance test

- Nox2:

-

NADPH oxidase isoform 2

- O2 − :

-

Superoxide anion

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

References

Defronzo RA (2009) Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 58:773–795

Nolan CJ, Damm P, Prentki M (2011) Type 2 diabetes across generations: from pathophysiology to prevention and management. Lancet 378:169–181

Weir GC, Laybutt DR, Kaneto H, Bonner-Weir S, Sharma A (2001) Beta-cell adaptation and decompensation during the progression of diabetes. Diabetes 50(Suppl 1):S154–S159

Antonetti DA, Klein R, Gardner TW (2012) Diabetic retinopathy. N Engl J Med 366:1227–1239

Ferrannini E, Cushman WC (2012) Diabetes and hypertension: the bad companions. Lancet 380:601–610

Beaudoin MS, Graham TE (2011) Methylxanthines and human health: epidemiological and experimental evidence. Handb Exp Pharmacol 200:509–548

Loopstra-Masters RC, Liese AD, Haffner SM, Wagenknecht LE, Hanley AJ (2011) Associations between the intake of caffeinated and decaffeinated coffee and measures of insulin sensitivity and beta cell function. Diabetologia 54:320–328

Bhupathiraju SN, Pan A, Manson JE, Willett WC, van Dam RM, Hu FB (2014) Changes in coffee intake and subsequent risk of type 2 diabetes: three large cohorts of US men and women. Diabetologia 57:1346–1354

Fredholm BB, Battig K, Holmen J, Nehlig A, Zvartau EE (1999) Actions of caffeine in the brain with special reference to factors that contribute to its widespread use. Pharmacol Rev 51:83–133

Fredholm BB, IJzerman AP, Jacobson KA, Linden J, Muller CE (2011) International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and classification of adenosine receptors–an update. Pharmacol Rev 63:1–34

Dhalla AK, Chisholm JW, Reaven GM, Belardinelli L (2009) A1 adenosine receptor: role in diabetes and obesity. Handb Exp Pharmacol: 271–295

Fredholm BB, Johansson S, Wang YQ (2011) Adenosine and the regulation of metabolism and body temperature. Adv Pharmacol 61:77–94

Johansson SM, Salehi A, Sandstrom ME et al (2007) A1 receptor deficiency causes increased insulin and glucagon secretion in mice. Biochem Pharmacol 74:1628–1635

Salehi A, Parandeh F, Fredholm BB, Grapengiesser E, Hellman B (2009) Absence of adenosine A1 receptors unmasks pulses of insulin release and prolongs those of glucagon and somatostatin. Life Sci 85:470–476

Yang GK, Fredholm BB, Kieffer TJ, Kwok YN (2012) Improved blood glucose disposal and altered insulin secretion patterns in adenosine A1 receptor knockout mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303:E180–190

Deshpande NA, McDonald TJ, Cook MA (1999) Endogenous interstitial adenosine in isolated myenteric neural networks varies inversely with prevailing PO2. Am J Physiol 276:G875–885

Collis MG (1989) The vasodilator role of adenosine. Pharmacol Ther 41:143–162

Carlsson PO, Olsson R, Kallskog O, Bodin B, Andersson A, Jansson L (2002) Glucose-induced islet blood flow increase in rats: interaction between nervous and metabolic mediators. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 283:E457–464

Chang AM, Halter JB (2003) Aging and insulin secretion. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E7–12

Gabriely I, Ma XH, Yang XM et al (2002) Removal of visceral fat prevents insulin resistance and glucose intolerance of aging: an adipokine-mediated process? Diabetes 51:2951–2958

Hanley AJ, Wagenknecht LE, Norris JM et al (2009) Insulin resistance, beta cell dysfunction and visceral adiposity as predictors of incident diabetes: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS) Family study. Diabetologia 52:2079–2086

Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM (2006) Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature 444:840–846

Ling C, Groop L (2009) Epigenetics: a molecular link between environmental factors and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes 58:2718–2725

Johansson B, Halldner L, Dunwiddie TV et al (2001) Hyperalgesia, anxiety, and decreased hypoxic neuroprotection in mice lacking the adenosine A1 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:9407–9412

Nagy TR, Clair AL (2000) Precision and accuracy of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for determining in vivo body composition of mice. Obes Res 8:392–398

Lai EY, Jansson L, Patzak A, Persson AE (2007) Vascular reactivity in arterioles from normal and alloxan-diabetic mice: studies on single perfused islets. Diabetes 56:107–112

Datla SR, Griendling KK (2010) Reactive oxygen species, NADPH oxidases, and hypertension. Hypertension 56:325–330

Carlstrom M, Brown RD, Yang T et al (2013) L-arginine or tempol supplementation improves renal and cardiovascular function in rats with reduced renal mass and chronic high salt intake. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 207:732–741

Johansson SM, Lindgren E, Yang JN, Herling AW, Fredholm BB (2008) Adenosine A1 receptors regulate lipolysis and lipogenesis in mouse adipose tissue-interactions with insulin. Eur J Pharmacol 597:92–101

Burnstock G, Novak I (2012) Purinergic signalling in the pancreas in health and disease. J Endocrinol 213:123–141

Kaminski DA, Randall TD (2010) Adaptive immunity and adipose tissue biology. Trends in immunology 31:384–390

Friedman JM, Halaas JL (1998) Leptin and the regulation of body weight in mammals. Nature 395:763–770

Galletti F, Barbato A, Versiero M et al (2007) Circulating leptin levels predict the development of metabolic syndrome in middle-aged men: an 8-year follow-up study. J Hypertens 25:1671–1677

Moran O, Phillip M (2003) Leptin: obesity, diabetes and other peripheral effects–a review. Pediatr Diabetes 4:101–109

Patel SB, Reams GP, Spear RM, Freeman RH, Villarreal D (2008) Leptin: linking obesity, the metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular disease. Curr Hypertens Rep 10:131–137

Sader S, Nian M, Liu P (2003) Leptin: a novel link between obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular risk, and ventricular hypertrophy. Circulation 108:644–646

Jansson L (1994) The regulation of pancreatic islet blood flow. Diabetes Metab Rev 10:407–416

Brunicardi FC, Stagner J, Bonner-Weir S et al (1996) Microcirculation of the islets of Langerhans. Long beach veterans administration regional medical education center symposium. Diabetes 45:385–392

Gao X, Patzak A, Sendeski M et al (2011) Adenosine A(1)-receptor deficiency diminishes afferent arteriolar and blood pressure responses during nitric oxide inhibition and angiotensin II treatment. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301:R1669–1681

Svensson AM, Sandler S, Jansson L (2003) Role of superoxide anion in pancreatic islet blood flow regulation in anesthetized rats. Eur J Pharmacol 459:59–64

Lee DL, Bell TD, Bhupatkar J, Solis G, Welch WJ (2012) Adenosine A1-receptor knockout mice have a decreased blood pressure response to low-dose ANG II infusion. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 303:R683–688

Youn JY, Siu KL, Lob H, Itani H, Harrison DG, Cai H (2014) Role of vascular oxidative stress in obesity and metabolic syndrome. Diabetes 63:2344–2355

Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS (2005) Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 115:1111–1119

Shu CJ, Benoist C, Mathis D (2012) The immune system’s involvement in obesity-driven type 2 diabetes. Semin Immunol 24:436–442

Odegaard JI, Chawla A (2013) The immune system as a sensor of the metabolic state. Immunity 38:644–654

Cildir G, Akincilar SC, Tergaonkar V (2013) Chronic adipose tissue inflammation: all immune cells on the stage. Trends Mol Med 19:487–500

Kosteli A, Sugaru E, Haemmerle G et al (2010) Weight loss and lipolysis promote a dynamic immune response in murine adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 120:3466–3479

Kern PA, Ranganathan S, Li C, Wood L, Ranganathan G (2001) Adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 expression in human obesity and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 280:E745–751

Hotamisligil GS, Arner P, Caro JF, Atkinson RL, Spiegelman BM (1995) Increased adipose tissue expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in human obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 95:2409–2415

Johnston-Cox H, Koupenova M, Yang D et al (2012) The A2b adenosine receptor modulates glucose homeostasis and obesity. PLoS One 7:e40584

Gnad T, Scheibler S, von Kugelgen I et al (2014) Adenosine activates brown adipose tissue and recruits beige adipocytes via A2A receptors. Nature 516:395–399

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Lindgren (Karolinska Institutet) and M. Quach (Uppsala University) for technical assistance and helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from the Swedish Research Council (521-2011-2639 to MC and 521-2011-3777 to LJ), Swedish Heart and Lung Foundation (20140448, 20110589), Jeanssons Foundation (JS2013-00064), Swedish Diabetes Foundation, an EXODIAb grant, Swedish Society of Medical Research (SSMF), the Wenner-Gren Foundation, the Family Ernfors Fund, the Swedish Society of Medicine and Novo Nordisk Foundation Excellence Project.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

MC, LJ, BBF and TY designed the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, and revised the article critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be published. MC is the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Ting Yang and Xiang Gao are joint first authors.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM Methods

(PDF 116 kb)

ESM Fig. 1

(PDF 3,340 kb)

ESM Fig. 2

(PDF 74 kb)

ESM Fig. 3

(PDF 121 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, T., Gao, X., Sandberg, M. et al. Abrogation of adenosine A1 receptor signalling improves metabolic regulation in mice by modulating oxidative stress and inflammatory responses. Diabetologia 58, 1610–1620 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3570-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-015-3570-3