Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Cardiovascular events and death are better predicted by postprandial glucose (PPG) than by fasting blood glucose or HbA1c. While chronic exercise reduces HbA1c in patients with type 2 diabetes, short-term exercise improves measures of insulin sensitivity but does not consistently alter responses to the OGTT. The purpose of this study was to determine whether short-term exercise training improves PPG and glycaemic control in free-living patients with type 2 diabetes, independently of the changes in fitness, adiposity and energy balance often associated with chronic exercise training.

Methods

Using continuous glucose monitors, PPG was quantified in previously sedentary patients with type 2 diabetes not using exogenous insulin (n = 13, age 53 ± 2 years, HbA1c 6.6 ± 0.2% (49.1 ± 1.9 mmol/mol)) during 3 days of habitual activity and during the final 3 days of a 7 day aerobic exercise training programme (7D-EX) which does not elicit measurable changes in cardiorespiratory fitness or body composition. Diet was standardised across monitoring periods, with modifications during 7D-EX to offset increases in energy expenditure. OGTTs were performed on the morning following each monitoring period.

Results

7D-EX attenuated PPG (p < 0.05) as well as the frequency, magnitude and duration of glycaemic excursions (p < 0.05). Conversely, average 24 h blood glucose did not change, nor did glucose, insulin or C-peptide responses to the OGTT.

Conclusions/interpretation

7D-EX attenuated glycaemic variability and PPG in free-living patients with type 2 diabetes but did not significantly alter responses to the laboratory-based OGTT. These effects appeared to be independent of changes in fitness, body composition or energy balance.

ClinicalTrials.gov numbers: NCT00954109 and NCT00972452.

Funding: This project was funded by the University of Missouri Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CRM), NIH grant T32 AR-048523 (CRM), Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (JPT). Medtronic supplied CGMS sensors at a discounted rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Glycaemic control is the primary focus of diabetes management. There is a strong, inverse association between HbA1c and the risk of diabetes-related complications, including micro- and macrovascular diseases and mortality [1]. Evidence from epidemiological analyses indicates that the largest reductions in risk occur when patients with poor glycaemic control achieve fair or good glycaemic control (HbA1c <7%), but that additional reductions in risk, albeit smaller, may be achieved by further lowering HbA1c (<6.0–6.5% [42.1–48.6 mmol/mol]) [1, 2]. Randomised controlled trials have demonstrated significant reductions in cardiovascular complications and death when HbA1c is lowered to 7% or below, but have failed to provide sufficient evidence to support amending the current guidelines to include a universal HbA1c target of 6.0–6.5% (42.1–48.6 mmol/mol) [3].

Three important trials, Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes (ACCORD), Action in Diabetes and Vascular Disease: Preterax and Diamicron MR Controlled Evaluation (ADVANCE), and the Veterans' Affairs Diabetes Trial (VADT), established that intensive pharmaceutical interventions to lower HbA1c below 6.0% or 6.5% (42.1–48.6 mmol/mol) were no more effective than standard therapy in reducing adverse cardiovascular outcomes [4–6]. On the contrary, the intensive glycaemic control arm of the ACCORD trial was terminated prematurely due to significantly higher rates of mortality [4]. Although it has been difficult to pinpoint the cause of the higher mortality rate associated with intensive glycaemic control, higher rates of severe hypoglycaemia might have contributed [7]. Intensive glycaemic control is associated with a twofold increase in severe hypoglycaemia over standard therapy [8], and recent severe hypoglycaemia was a significant predictor of cardiovascular events and death in VADT [6]. Thus, there remains a need to identify safe, effective interventions to improve glycaemic control while simultaneously reducing glycaemic variability and minimising hypoglycaemic events.

While HbA1c is strongly predictive of diabetes-related complications and events, it is an index of long-term glycaemic control and does not provide insight into changes in glycaemic variability or hypoglycaemia [9]. Thus, even as HbA1c is lowered together with decreases in average blood glucose, increases in the magnitude, frequency or duration of hypoglycaemia or glycaemic variability may go undetected. Furthermore, HbA1c does not distinguish pre- and postprandial conditions. These are considerable limitations given that hypoglycaemia initiates many of the same complications as hyperglycaemia (reviewed in [10]), and, because large fluctuations in blood glucose trigger physiological events thought to drive the micro- and macrovascular complications associated with type 2 diabetes [11], elevated glycaemic variability may be more damaging or additive to the complications caused by chronic hyperglycaemia [12, 13]. Correspondingly, mounting evidence points to postprandial glucose (PPG) as a better predictor of cardiovascular disease and death than fasting blood glucose or HbA1c [12–16], indicating that direct measures of PPG are warranted.

As part of a healthy lifestyle, exercise has been shown to be more effective than some pharmacological agents in preventing the progression of prediabetes to overt type 2 diabetes [17]. Chronic exercise training reduces HbA1c and is recognised by national and international health organisations as a key component of diabetes prevention and management [18–20]. The beneficial effects of exercise are commonly attributed to adaptations to exercise training, such as improvements in fitness, muscle oxidative capacity or body composition [21, 22]. However, 7 day aerobic exercise training programmes that do not measurably alter these factors [23, 24] consistently improve insulin sensitivity but not responses to the OGTT in patients with type 2 diabetes [23, 25, 26]. Because traditional measures of glycaemic control do not directly assess blood glucose in free-living persons consuming mixed meals, the specific effects of exercise on PPG and glycaemic variability, independently of changes in fitness or body weight and/or composition in patients with type 2 diabetes, are not clear.

In the current study we measured the effect of 7 days of aerobic exercise on PPG and glycaemic variability in free-living individuals with type 2 diabetes using a continuous glucose monitoring system (CGMS) and laboratory-based measures of glucose tolerance determined by OGTT. Additional snacks were provided during the 7-day exercise programme in order to offset increases in energy expenditure. This enabled us to examine the specific effects of short-term exercise on glycaemic control in free-living patients with type 2 diabetes, independently of changes in fitness, muscle oxidative capacity, body composition or energy balance.

Methods

Subjects and design

The investigation was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000. Protocols were approved by the University of Missouri Health Sciences Institutional Review Board, and written informed consent was obtained from all volunteers.

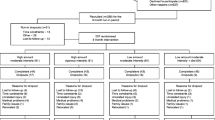

Overweight and obese (BMI 25–43 kg/m2), sedentary (<60 min structured exercise/week) volunteers aged 30–65 years with type 2 diabetes not requiring exogenous insulin were recruited. Participants were screened via detailed medical history questionnaire, physical examination, graded exercise test, and blood and urine analysis. Exclusion criteria included: HbA1c ≥10% (85.8 mmol/mol), evidence of advanced cardiovascular, renal or hepatic diseases, contraindications to exercise training, body weight change ≥3% within 6 months, medication change within 3 months, and smoking. Of the 67 participants screened, 13 were eligible for participation.

Experimental design

Glycaemic control was assessed by continuous glucose monitoring (iPro CGM; Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA) during 3 days of habitual, sedentary activity (baseline) and during the final 3 days of a 7 day aerobic exercise training programme (7D-EX). Fasting-state OGTTs were performed on the morning immediately following each monitoring period.

Exercise intervention

The exercise programme consisted of 60 min of supervised exercise (alternating 20 min of treadmill walking and stationary cycling) for 7 consecutive days at 60–75% heart rate reserve, as previously described [27]. Resting heart rate (HRrest) and peak heart rate (HRpeak) values obtained from the cardiorespiratory fitness test were used to calculate the target heart rate (THR) by the Karvonen method: \( {\text{THR}} = \left[ {\left( {{\text{H}}{{\text{R}}_{\text{peak}}} - {\text{H}}{{\text{R}}_{\text{rest}}}} \right) \times \% {\text{intensity}}} \right] + {\text{H}}{{\text{R}}_{\text{rest}}} \) [28].

Fitness and anthropometrics

Cardiorespiratory fitness (peak oxygen consumption [\( \dot{V}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2peak}}} \)]) was determined by indirect calorimetry (TrueOne 2400; Parvo Medics, Salt Lake City, UT, USA) during a graded exercise test on a Monarch bicycle ergometer (Monarch, Varberg, Sweden) as previously described [27]. Height, weight and body composition (dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry: Hologic QDR 4500A; Hologic, Waltham, MA, USA) were measured at baseline.

Continuous glucose monitoring

During the evening prior to each 3 day monitoring period, a glucose sensor was inserted subcutaneously in the periumbilical region and connected to the CGMS. Participants were allotted ≥3 h between meals and snacks and recorded the exact timing and composition of each meal. Diet was strictly standardised across both monitoring periods, and additional snacks were provided during 7D-EX to offset increases in energy expenditure and minimise changes in energy balance. Energy expenditure during the exercise bout was estimated using American College of Sports Medicine calculations [29]. Diet records were analysed for macronutrient content using Food Processor SQL (ESHA Research, Salem, OR, USA). Participants recorded the results of four or more fingerstick glucose readings (Accu-Chek Compact Plus; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) each day for CGMS calibration. CGMS data were processed using Solutions Software for iPro CGM. PPG and PPG excursions (∆PPG; postmeal minus premeal blood glucose) were determined at 30 min postmeal intervals, as previously described [30]. According to guidelines from the ADA, the threshold for high glucose excursions was set at >10 mmol/l, and the threshold for low excursions was set at <4 mmol/l [3].

OGTT

OGTTs (75 g glucose) were performed after an overnight (10–12 h) fast at the same time of day across phases. Participants refrained from exercise and medication use on the morning of testing. Post-intervention OGTTs were performed within 12–24 h of the final bout of exercise, as previously described [26, 27, 31]. Blood samples were collected at 30 min intervals for measurement of glucose by the glucose oxidase method (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and insulin and C-peptide by chemiluminescent enzyme immunoassay (Immulite 1000 Analyzer; Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL, USA). The AUC for glucose, insulin and C-peptide responses to the OGTT was calculated using the trapezoidal method.

The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance was calculated from fasting glucose and insulin concentrations [32], and the Matsuda insulin sensitivity index was calculated from the glucose and insulin values at different time points during the OGTT [33].

Statistical analysis

There was no effect of meal or day on PPG or ∆PPG (i.e. within each phase, PPG and ΔPPG were not different between meals or across days and did not interact with the change in PPG or ∆PPG during 7D-EX). Therefore, PPG and ∆PPG were pooled across all meals and all days within each 3 day phase to calculate individual means (i.e. mean PPG and ΔPPG for each patient averaged for every meal during each 3 day phase) for analysis, as previously described [30]. Differences in pre- and postintervention PPG and ∆PPG were detected using two-way repeated measures ANOVA (time × treatment), as previously described [30]. Tukey post hoc testing was applied to identify specific between-phase differences. Paired t tests were performed to detect phase differences in paired observations. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05; all data are expressed as means±SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

All 13 (eight men, five women) sedentary, obese individuals with type 2 diabetes (HbA1c 6.64 ± 0.16% (49.1 ± 1.8 mmol/mol)) completed the study (Table 1).

Physical activity and energy balance

Sedentary individuals with type 2 diabetes acquired 5,801 ± 770 steps/day at baseline and 6,049 ± 806 steps/day, excluding steps taken during the exercise sessions, during 7D-EX (Table 1), suggesting habitual activity was not altered by the exercise intervention. Compliance with 7D-EX was 100%. Participants expended an estimated 112 ± 8 kJ per exercise session and consumed an additional 89 ± 20 kJ/day during 7D-EX.

Glycaemic control

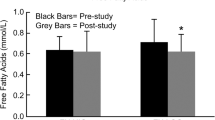

Average 24 h blood glucose concentrations did not change significantly during 7D-EX. However, maximum daily blood glucose was lowered (p < 0.05), the difference between minimum and maximum daily blood glucose was reduced (p < 0.05), the number of high (p < 0.07) and low (p < 0.05) glucose excursions per day was reduced, and the amount of time spent both above (p < 0.07) and below (p < 0.05) the high and low glucose limits was also reduced (Table 2). Likewise, PPG, peak PPG, and ∆PPG were reduced during 7D-EX (p < 0.05; Fig. 1). Premeal blood glucose concentrations did not change.

Mean PPG (a) and ∆PPG (b) in patients with type 2 diabetes during 3 days of habitual physical activity (baseline; white squares) and during the final 3 days of a 7 day aerobic exercise training programme (7D-EX; black circles). *p < 0.05 (significantly different from corresponding baseline time point)

Glucose tolerance

Fasting glucose, insulin and C-peptide, as well as glucose, insulin and C-peptide responses to the OGTT, were largely unaltered by the exercise intervention (Table 3).

Discussion

These data demonstrate that 7 days of aerobic exercise training reduces PPG and glycaemic variability in free-living individuals with type 2 diabetes but does not influence responses to the laboratory-based OGTT.

The health benefits of exercise training, including improvements in insulin sensitivity and glycaemic control, are commonly attributed to the adaptations associated with chronic exercise, including increases in cardiorespiratory fitness, changes in energy balance, or reductions in total or regional adiposity [21, 22]. In the present study we implemented a 7 day aerobic exercise programme that does not significantly change fitness or adiposity [23], and we provided supplemental food to offset increases in energy expenditure due to the exercise training programme, allowing us to ascertain the specific effects of exercise on glycaemic control. Therefore, the data presented here provide new evidence that daily exercise directly improves glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes, prior to changes in fitness or adiposity and independently of changes in energy balance.

In agreement with previous studies, we did not observe significant changes in fasting glucose, insulin or C-peptide after 7D-EX in patients with type 2 diabetes, nor did we observe changes in the glucose, insulin or C-peptide responses to the OGTT. By contrast, we did observe significant changes in the postprandial response to meal ingestion as well as in glycaemic variability using CGMS, indicating that CGMS may be a more sensitive tool to detect changes in glucose control in patients with type 2 diabetes.

It is not yet clear why changes in PPG were captured by CGMS under free-living conditions but not by the laboratory-based OGTT. However, the differences in the macronutrient content of the glucose drink consumed during the OGTT (100% of energy from carbohydrate ) and the mixed meals consumed during CGMS monitoring (60% of energy from carbohydrate, 24% from fat and 14% from protein) would differentially influence rates of absorption, gastric emptying and insulin secretion and might have been a contributing factor. Furthermore, these data agree with findings from others and suggest that responses to the OGTT may not be indicative of day-to-day glycaemic control [30, 34]. Similarly, whereas 7 days of exercise training typically improves insulin sensitivity measured via the hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp in patients with type 2 diabetes [26], responses to the OGTT are generally unaffected [27]. Prior investigations using the clamp and OGTT have provided important experimental insight into the effects of exercise on insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance. However, as evidenced here, traditional measures of glycaemic control do not adequately reflect PPG responses to mixed-meal ingestion under free-living conditions [35–37], and therefore may not provide the most accurate insight into the effect of short-term exercise training on PPG in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Here we present new evidence that daily exercise improves day-to-day glycaemic control, reducing the frequency, magnitude and duration of glycaemic excursions in previously sedentary patients with type 2 diabetes under free-living conditions. Moreover, these favourable changes occurred without increasing the prevalence of hypoglycaemia, which is thought to cause many of the same complications as elevated blood glucose (reviewed by Dandona et al. [10]).

Although these data provide evidence that exercise directly modulates PPG, the precise time course for these changes is unclear. We did not observe significant differences in PPG across treatment days (within days 5–7 of 7D-EX), indicating that the improvement in glycaemic control occurred quickly. Nonetheless, we speculate that glycaemic control would improve further with chronic exercise in patients with type 2 diabetes, as longer training regimens commonly produce structural and functional adaptations that influence insulin sensitivity, including increases in skeletal muscle mitochondrial content, oxidative capacity and capillary density.

While these data are promising, the volume of exercise used in this study is above the amount currently recommended for patients with type 2 diabetes [18]. Additional studies are warranted to determine the precise mode, frequency, amount and intensity of exercise necessary to optimise glycaemic control in this population and to determine whether similar results may be obtained in more diverse populations in those treated with insulin therapies or with uncontrolled type 2 diabetes.

Finally, the advantages and limitations associated with the CGMS technology should be considered. There is a well-documented lag time between the equilibrium of glucose in the capillary blood measured by traditional glucometers and the interstitial fluid measured by the CGMS [38, 39]. At times when blood glucose concentrations are changing at very high rates (>27 mmol/l per min), the delay may result in an underestimation of the rate of change in blood glucose concentrations [40] or failure to detect rapid, transitory excursions [41]. However, CGMS has been validated against measures of venous and capillary blood as a tool to measure glycaemic responses to meal ingestion [42], and exercise does not appear to influence the duration of the lag time between changes in capillary and interstitial glucose [38], the relative difference (~15%) in CGMS and glucometer recordings [41], or the rate of accurately identifying hypoglycaemic excursions in patients with type 1 diabetes [41]. Thus, it is unlikely that exercise appreciably influenced the accuracy or reliability of the CGMS measures in the present study. Furthermore, unlike laboratory-based measures of insulin sensitivity (hyperinsulinaemic–euglycaemic clamp), glucose tolerance (OGTT) or long-term glycaemic control (HbA1c), the CGMS records minute-to-minute measures of blood glucose over multiple days, allowing direct quantification of the magnitude and duration of PPG in free-living individuals consuming mixed meals [43].

In summary, we demonstrate that short-term daily exercise reduces PPG and glycaemic variability in patients with type 2 diabetes and does not produce the increases in the incidence of hypoglycaemia sometimes associated with some intensive pharmacological interventions. These data also show that the effects of exercise to improve glycaemic control take place quickly, are not reliant on adaptations to chronic exercise and are not reflected by changes in the response to the laboratory-based OGTT. Overall, our findings reinforce the utility of daily exercise to reduce glycaemic variability quickly and safely in patients with well-controlled type 2 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- 7D-EX:

-

7 Day aerobic exercise training programme

- CGMS:

-

Continuous glucose monitoring system

- PPG:

-

Postprandial glucose

- ∆PPG:

-

Postprandial glucose excursions

- \( \dot{V}{{\text{O}}_{\text{2peak}}} \) :

-

Peak oxygen consumption

References

Stratton IM, Adler AI, Neil HA et al (2000) Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ 321:405–412

The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (1993) The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 329:977–986

Association AD (2010) Standards of medical care in diabetes–2010. Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1):S11–S61

Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP et al (2008) Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358:2545–2559

Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J et al (2008) Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 358:2560–2572

Duckworth W, Abraira C, Moritz T et al (2009) Glucose control and vascular complications in veterans with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 360:129–139

Skyler JS, Bergenstal R, Bonow RO et al (2009) Intensive glycemic control and the prevention of cardiovascular events: implications of the ACCORD, ADVANCE, and VA diabetes trials: a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and a scientific statement of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association. Diabetes Care 32:187–192

Boussageon R, Bejan-Angoulvant T, Saadatian-Elahi M et al (2011) Effect of intensive glucose lowering treatment on all cause mortality, cardiovascular death, and microvascular events in type 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 343:d4169

Sacks DB, Bruns DE, Goldstein DE, Maclaren NK, McDonald JM, Parrott M (2002) Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem 48:436–472

Dandona P, Chaudhuri A, Dhindsa S (2010) Proinflammatory and prothrombotic effects of hypoglycemia. Diabetes Care 33:1686–1687

Wright E Jr, Scism-Bacon JL, Glass LC (2006) Oxidative stress in type 2 diabetes: the role of fasting and postprandial glycaemia. Int J Clin Pract 60:308–314

Temelkova-Kurktschiev TS, Koehler C, Henkel E, Leonhardt W, Fuecker K, Hanefeld M (2000) Postchallenge plasma glucose and glycemic spikes are more strongly associated with atherosclerosis than fasting glucose or HbA1c level. Diabetes Care 23:1830–1834

Cederberg H, Saukkonen T, Laakso M et al (2010) Postchallenge glucose, HbA1c, and fasting glucose as predictors of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease: a 10-year prospective cohort study. Diabetes Care 33:2077–2083

Levitan EB, Song Y, Ford ES, Liu S (2004) Is nondiabetic hyperglycemia a risk factor for cardiovascular disease? A meta-analysis of prospective studies. Arch Intern Med 164:2147–2155

Saydah SH, Miret M, Sung J, Varas C, Gause D, Brancati FL (2001) Postchallenge hyperglycemia and mortality in a national sample of U.S. adults. Diabetes Care 24:1397–1402

Cavalot F, Pagliarino A, Valle M et al (2011) Postprandial blood glucose predicts cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in type 2 diabetes in a 14-year follow-up: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care 34:2237–2243

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE et al (2002) Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 346:393–403

Colberg SR, Sigal RJ, Fernhall B et al (2010) Exercise and type 2 diabetes: the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Diabetes Association: joint position statement. Diabetes Care 33:e147–e167

Umpierre D, Ribeiro PA, Kramer CK et al (2011) Physical activity advice only or structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc 305:1790–1799

Church TS, Blair SN, Cocreham S et al (2010) Effects of aerobic and resistance training on hemoglobin A1c levels in patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA: J Am Med Assoc 304:2253–2262

Bassuk SS, Manson JE (2005) Epidemiological evidence for the role of physical activity in reducing risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Appl Physiol 99:1193–1204

Heath GW, Gavin JR 3rd, Hinderliter JM, Hagberg JM, Bloomfield SA, Holloszy JO (1983) Effects of exercise and lack of exercise on glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity. J Appl Physiol 55:512–517

Kirwan JP, Solomon TP, Wojta DM, Staten MA, Holloszy JO (2009) Effects of 7 days of exercise training on insulin sensitivity and responsiveness in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297:E151–E156

Rogers MA, Yamamoto C, King DS, Hagberg JM, Ehsani AA, Holloszy JO (1988) Improvement in glucose tolerance after 1 wk of exercise in patients with mild NIDDM. Diabetes Care 11:613–618

Winnick JJ, Sherman WM, Habash DL et al (2008) Short-term aerobic exercise training in obese humans with type 2 diabetes mellitus improves whole-body insulin sensitivity through gains in peripheral, not hepatic insulin sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:771–778

Kang J, Robertson RJ, Hagberg JM et al (1996) Effect of exercise intensity on glucose and insulin metabolism in obese individuals and obese NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care 19:341–349

Mikus CR, Fairfax ST, Libla JL et al (2011) Seven days of aerobic exercise training improves conduit artery blood flow following glucose ingestion in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Appl Physiol 111:657–664

Karvonen J, Vuorimaa T (1988) Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities. Practical application. Sports Med 5:303–311

American College of Sports Medicine (2010) ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription, 8th edn. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA

Mikus CR, Oberlin DJ, Libla JL, Taylor AM, Booth FW, Thyfault JP (2012) Lowering physical activity impairs glycemic control in healthy volunteers. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44:225–231

Angelopoulos TJ, Schultz RM, Denton JC, Jamurtas AZ (2002) Significant enhancements in glucose tolerance and insulin action in centrally obese subjects following ten days of training. Clin J Sport Med 12:113–118

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28:412–419

Matsuda M, DeFronzo RA (1999) Insulin sensitivity indices obtained from oral glucose tolerance testing: comparison with the euglycemic insulin clamp. Diabetes Care 22:1462–1470

Hasson RE, Freedson PS, Braun B (2010) Use of continuous glucose monitoring in normoglycemic, insulin-resistant women. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 108:1181–1187

Avignon A, Radauceanu A, Monnier L (1997) Nonfasting plasma glucose is a better marker of diabetic control than fasting plasma glucose in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 20:1822–1826

Cavalot F, Petrelli A, Traversa M et al (2006) Postprandial blood glucose is a stronger predictor of cardiovascular events than fasting blood glucose in type 2 diabetes mellitus, particularly in women: lessons from the San Luigi Gonzaga Diabetes Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91:813–819

Bonora E, Muggeo M (2001) Postprandial blood glucose as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease in type II diabetes: the epidemiological evidence. Diabetologia 44:2107–2114

Boyne MS, Silver DM, Kaplan J, Saudek CD (2003) Timing of changes in interstitial and venous blood glucose measured with a continuous subcutaneous glucose sensor. Diabetes 52:2790–2794

Steil GM, Rebrin K, Mastrototaro J, Bernaba B, Saad MF (2003) Determination of plasma glucose during rapid glucose excursions with a subcutaneous glucose sensor. Diabetes Technol Ther 5:27–31

Weinstein RL, Schwartz SL, Brazg RL, Bugler JR, Peyser TA, McGarraugh GV (2007) Accuracy of the 5-day FreeStyle Navigator Continuous Glucose Monitoring System: comparison with frequent laboratory reference measurements. Diabetes Care 30:1125–1130

Buckingham BA, Kollman C, Beck R et al (2006) Evaluation of factors affecting CGMS calibration. Diabetes Technol Ther 8:318–325

Wallace AJ, Willis JA, Monro JA, Frampton CM, Hedderley DI, Scott RS (2006) No difference between venous and capillary blood sampling and the Minimed continuous glucose monitoring system for determining the blood glucose response to food. Nutr Res (New York, NY) 26:403–408

Hay LC, Wilmshurst EG, Fulcher G (2003) Unrecognized hypo- and hyperglycemia in well-controlled patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the results of continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther 5:19–26

Funding

This project was funded by the University of Missouri Institute for Clinical and Translational Sciences (CRM), NIH grant T32 AR-048523 (CRM), Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (JPT). Medtronic supplied CGMS sensors at a discounted rate. We also thank A. Choudhary for providing medical coverage for our study.

Duality of interest

The authors declare that there is no duality of interest associated with this manuscript.

Contribution statement

CRM and JPT made substantial contributions to the conception of the study and drafting the article. CRM, JPT, DJO, JL, and LJB all contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data, revising it critically for important intellectual content, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikus, C.R., Oberlin, D.J., Libla, J. et al. Glycaemic control is improved by 7 days of aerobic exercise training in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 55, 1417–1423 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2490-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-012-2490-8