Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

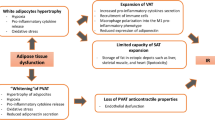

Increased adipose tissue secretion of adipokines and cytokines has been implicated in the chronic low-grade inflammation state and insulin resistance associated with obesity. We tested here whether the cardiovascular and metabolic hormone atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) was able to modulate adipose tissue secretion of several adipokines (derived from adipocytes) and cytokines (derived from adipose tissue macrophages).

Subjects and methods

We used protein array to measure the secretion of adipokines and cytokines after a 24-h culture of human subcutaneous adipose tissue pieces treated or not with a physiological concentration of ANP. The effect of ANP on protein secretion was also directly studied on isolated adipocytes and macrophages. Gene expression was measured by real-time RT-quantitative PCR.

Results

ANP decreased the secretion of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and TNF-α, of several chemokines, and of the adipokines leptin and retinol-binding protein-4 (RBP-4). The secretion of the anti-inflammatory molecules IL-10 and adiponectin remained unaffected. The cytokines were mainly expressed in macrophages that expressed all components of the ANP-dependent signalling pathway. The adipokines, leptin, adiponectin and RBP-4 were specifically expressed in mature adipocytes. ANP directly inhibited the secretion of IL-6 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 by macrophages. The inhibitory effects of ANP on leptin and growth-related oncogene-α secretions were not seen under selective hormone-sensitive lipase inhibition.

Conclusions/interpretation

We suggest that ANP, either by direct action on adipocytes and macrophages or through activation of adipocyte hormone-sensitive lipase, inhibits the secretion of factors involved in inflammation and insulin resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic low-grade inflammation, as defined by increased plasma levels of C-reactive protein, is a strong risk factor for cardiovascular and metabolic diseases [1–4]. Additional markers of inflammation such as IL-6 and TNF-α are strongly associated with increased risk of several chronic diseases including insulin resistance, coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus [5, 6]. Mounting evidence indicates that obesity is associated with a chronic systemic low-grade inflammatory state and that inflammation is one of the potential mechanisms of obesity-related morbidity [2, 7].

Adipose tissue is an important endocrine tissue that secretes many biologically active proteins, such as adiponectin, leptin, retinol-binding protein-4 (RBP-4) and numerous cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-8, IL-10 and IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra, also known as IL1RN) [8]. All these factors are collectively termed adipokines for those secreted by adipocytes and cytokines for those secreted by other adipose tissue stromal cells. Plasma levels of several adipokines and cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, MCP-1, RBP-4) are increased during obesity [9–12]. They are thought to play a critical role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. In recent studies, there is evidence of macrophage infiltration and accumulation in the subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue from overweight and obese individuals [13–15]. Macrophages recruited in adipose tissue might be a noticeable source of inflammatory cytokines.

Although many adipose tissue-secreted cytokines and adipokines have been identified, the nutritional and endocrine signals that regulate the secretion of these molecules are poorly understood so far. Atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) is a cardiovascular hormone secreted by cardiomyocytes involved in the control of blood volume homeostasis through natriuretic and diuretic effects [16]. The physiological role of natriuretic peptides (NPs) in the cardiovascular system has been extensively studied in the past 20 years. More recently, ANP has been shown to stimulate lipolysis in human fat cells [17]. The intracellular signal pathway involves cyclic GMP production, cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I (cGKI) activation, and hormone-sensitive lipase (HSL) phosphorylation and activation. ANP stimulates lipolysis specifically in primate and human adipocytes. The physiological relevance of the lipolytic effect of ANP has been demonstrated in humans and recently reviewed [18]. However, besides the potent lipolytic effect of ANP in human adipocytes, the potential impact of ANP on adipokine production by adipocytes and cytokine production by adipose tissue macrophages is unknown. In the present study, we tested whether ANP was able to modulate the secretion of several cytokines and adipokines linked to inflammation and insulin resistance directly or indirectly through metabolic products originating from lipolysis.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

Subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue was obtained from 18 overweight women undergoing plastic surgery. Their mean age was 44.6 ± 2.9 years and their mean BMI was 27.5 ± 1.2 kg/m2. The study was in agreement with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the French National Institute of Health and Medical Research (INSERM) and the Toulouse University Hospital ethics regulation. Adipose tissue was used either for culture of human adipose tissue pieces or for isolation of adipocytes and macrophages.

Culture of human adipose tissue pieces

Human adipose tissue pieces contain the different cell types of adipose tissue and permit long-term culture [19, 20]. Thus, primary culture of adipose tissue pieces offers the unique possibility to study whole-tissue secretion.

On day 1, 30 g of subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue were cut with scissors under aseptic conditions into small pieces weighing approximately 10 mg or less. In all experiments, pieces were washed three times with sterile PBS to remove blood cells. The pieces of adipose tissue were centrifuged for 1 min at 300 × g at room temperature between each wash. Then 20 g of the pieces of tissue was resuspended in 50 ml of fresh medium containing 10% FCS. The culture medium used was DMEM F12 (Cambrex, Verviers, Belgium) containing 33 μmol/l biotin, 17 μmol/l pantothenate and 50 μg/ml gentamicin. The pieces were preincubated overnight in aseptic conditions to allow for removal of soluble factors and cellular debris released by cells broken during the preparation of the small pieces of adipose tissue.

On day 2, the pieces were washed three times with PBS to remove excess serum and debris, and centrifuged for 1 min at 300 × g at room temperature. Then, the pieces (200 mg/ml) were incubated for 24 h in control conditions, and treated with a physiological dose of ANP (10 nmol/l) alone or in combination with 4-isopropyl-3-methyl-2-([(3S)-3-methylpiperidin-1-yl] carbonyl) isoxazol-5(2H)-one (BAY), a specific HSL inhibitor, at 1 μmol/l [21, 22]. The culture medium was DMEM F12 containing 33 μmol/l biotin, 17 μmol/l pantothenate and 50 μg/ml gentamicin, supplemented with 10 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (chymotrypsin 1.5 μg/ml, thermolysin 0.8 μg/ml, papain 1 mg/ml, pronase 1.5 μg/ml, pancreatic extract 1.5 μg/ml and trypsin 0.002 μg/ml) (Complete; Roche Diagnostic, Meylan, France). In all experiments, the concentration of BSA was kept constant to avoid any interaction of BSA with adipokine secretion [23]. The culture medium was adjusted to pH 7.4 and filtered through a 0.22-μm filter. Preliminary experiments showed that a 24-h incubation allowed the detection of a wide range of factors produced by adipose tissue. Aliquots of the medium were taken after 24 h of incubation and stored at −80°C for protein measurements. The pieces were washed three times with PBS, drained, weighed and stored at −80°C for mRNA analysis.

Cytokine arrays

The RayBio Human Cytokine Antibody Array C Series 1000 kit (RayBiotech Inc., Cliniscience, Montrouge, France) provides a simple array format, and is a highly sensitive approach to simultaneously detect a wide range of multiple cytokine secretion levels from conditioned media (for details see website: http://www.raybiotech.com/map/C_Series_1000.pdf) [24]. This kit combines two antibody array membranes to detect expression of 120 cytokines, mainly pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and angiogenic factors, in a single experiment. The experiment was performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 ml of conditioned medium was added to an antibody-coated membrane and incubated on a plate shaker at 4°C overnight. After incubation with biotinylated antibodies and labelled streptavidin, the signal was detected from the membrane by chemiluminescence. Data analysis was performed using ScanAlyze software to generate an absolute analysis of each membrane. As determined by densitometry, the variation between two spots was 5.7% (range 1–10%) in duplicate experiments. Positive controls were used to normalise the results from different membranes being compared. The relative secretion (arbitrary units [AU]/g of tissue) was normalised to the respective weight of the pieces.

Culture of human mature adipocytes

Adipocytes were isolated by collagenase digestion according to Rodbell [25]. After digestion, the suspension was filtered (210-μm filter) and washed three times with PBS. Mature adipocytes (1 ml) were included in fibrin gels (1.5 mg fibrinogen/ml in medium supplemented with 25 units/ml α-thrombin) and cultured in medium containing 10 mg/ml fatty acid-free BSA. Mature adipocytes were cultured for 24 h in the basal condition and in the presence of 1 μmol/l ANP. Control gels were prepared without adipocytes. After incubation, the adipocyte-conditioned media were frozen at −80°C and total lipids were extracted gravimetrically [26]. This technique avoids cell breakage and allows maintenance in culture of mature adipocytes.

Isolation and culture of human adipose tissue macrophages

The adipose tissue pieces were digested with collagenase (300 units/ml in PBS and 2% BSA). Following a 200 × g centrifugation, the pellet containing the stroma vascular fraction was incubated for 10 min in an erythrocyte-lysing buffer (155 mmol/l NH4Cl, 5.7 mmol/l K2HPO4 and 0.1 mmol/l EDTA) and finally resuspended in PBS/2% FCS and sequentially filtered through 100-, 70- and 40-μm filters.

The CD14+ cells, defined as adipose tissue macrophages, were isolated from the stroma vascular fraction as previously described in Curat et al. [14, 27] with minor modifications. One aliquot of the CD14+ cell population (adipose tissue macrophages) was collected in RNA lysis buffer (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) and stored at −80°C until analysis. Then, adipose tissue-derived macrophages were cultured in ECBM medium (Promocell, Heidelberg, Germany) containing 1% BSA in the presence or absence of ANP (1 μmol/l) for 24 h at 37°C. At the end of the incubation, the medium was collected and frozen at −80°C until analyses.

Determination of protein levels

Human leptin and adiponectin ELISA kits (BioVendor, Brno, Czech Republic) were used for the determination of leptin and adiponectin concentrations in medium. Within-run CV values for leptin and adiponectin were 2.5 and 3.3%, respectively. Quantikine human immunoassays (R&D Systems, Abingdon, Oxon, UK) were used for the quantification of growth-related oncogene (GRO)-α, IL-6 and MCP-1. Within-run CV values were 3.0, 1.6 and 2.6% for GRO-α, IL-6 and MCP-1, respectively. RBP-4 was not spotted on the cytokine array membranes and was measured independently in media by ELISA (Phoenix Europe GmbH, Karlsruhe, Germany); the within-run CV was 2.2%.

Lipolysis measurement

Lipolytic activity of adipose tissue pieces was determined by glycerol and NEFA concentrations. Glycerol was measured using a previously described method [28]. NEFA levels were assayed with an enzymatic method (Oxoid, Unipath, Dardilly, France). Glycerol and NEFA values were normalised as μmol/g tissue.

RNA extraction and real-time PCR

Gene expression was performed on adipose tissue pieces, macrophages and adipocytes. Total mRNA and reverse transcription were performed as previously described [22]. Real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on an ABI PRISM 7500 Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). A set of primers was designed for ADIPOQ (adiponectin), LEP (leptin), TNF (TNF-α), NPR1 (natriuretic peptide receptor A) and NPR3 (natriuretic peptide receptor C) using the software Primer Express 1.5 (Applied Biosystems) and used at a final concentration of 900 nmol/l with SYBR-Green based chemistry. To verify that genomic DNA was not amplified, qPCR was performed on reverse transcription reactions with no addition of reverse transcriptase. Primers and probes for IL6, CCL2 (also known as MCP-1), IL10, CXCL1 (also known as GRO-α), CCL4 (also known as macrophage inflammatory protein [MIP]-1-β), CCL8 (also known as MCP-2), PRKG1 (also known as cGKI), PDE5A (phosphodiesterase 5A) and RBP4 were obtained from Applied Biosystems using TaqMan probe-based assays. For each primer pair, a standard curve was obtained using serial dilutions of human adipose tissue cDNA prior to mRNA quantification. We used 18S ribosomal RNA (Ribosomal RNA Control TaqMan Assay kit; Applied Biosystems) as control to normalise gene expression. Each sample was performed in duplicate and 10 ng cDNA were used as a template for real-time PCR. When the difference between the duplicates was above 0.5 Ct, qPCR was performed again.

Statistical analyses

Data are presented as means±SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 12.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A non-parametric Wilcoxon test was used for statistical analyses of paired values. The effect of multiple treatments was analysed using a one-way ANOVA followed by an LSD post-hoc test. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Effect of ANP on human adipose tissue protein secretion

Cytokine arrays were used to screen conditioned media of human adipose tissue pieces (Fig. 1). Amongst 120 cytokines tested, leptin, adiponectin, IL-6, IL-8, the regulated upon activation normally T-expressed and presumably secreted (RANTES) factor, MCP-1, MIP-1β and GRO-α showed a high secretion rate (Fig. 2). Treatment of adipose tissue pieces with a physiological concentration of ANP (10 nmol/l) led to a statistically significant decrease of leptin, IL-6, TNF-α and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1, as well as of several chemokines (MCP-1, MIP-1β, MCP-2 and GRO-α) (Table 1). ANP treatment did not induce significant changes in the secretion of the anti-inflammatory molecules IL-10 and adiponectin. To confirm the results obtained with cytokine arrays, ELISA were performed to measure leptin, adiponectin and GRO-α as well as RBP-4, an adipokine recently described to be involved in obesity-associated insulin resistance [12]. As shown in Table 2, ANP treatment reduced the secretion of leptin, GRO-α and RBP-4 (25, 24 and 36% inhibition, respectively), whereas the secretion rate of adiponectin remained unaffected. Changes in protein secretion under ANP treatment were not associated with changes in gene expression of LEP, TNF, IL6 and CXCL1 in adipose tissue pieces (data not shown).

Cytokine antibody arrays membranes were used to detect adipokines, cytokines and chemokines produced by human adipose tissue. RayBiotech membranes coated with antibodies directed against various cytokines and chemokines were probed with supernatant of human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue cultured for 24 h. The relative cytokine level was determined by chemiluminescence detection. The figure shows a representative array of non-treated adipose tissue-conditioned media. HGF, hepatocyte growth factor

Baseline secretion rates of various adipokines, chemokines and cytokines in adipose tissue-conditioned media after 24 h of culture. Relative secretion was normalised by gram of tissue. Each autoradiograph (see Fig. 1) was quantified using image analysis software. Means±SEM of ten independent cultures from ten different donors. ENA-78, neutrophil-activating peptide; GM-CSF, granulocyte monocyte colony stimulating factor; HGF hepatocyte growth factor

Cellular origin of the ANP-sensitive adipokines and expression of the components of the ANP-dependent signalling pathway

The relative expression of several cytokines and adipokines was measured in macrophages and in mature adipocytes isolated from fresh human adipose tissue (Table 3). Leptin, adiponectin and RBP-4 were exclusively expressed in adipocytes. The chemokines, CXCL1, CCL2, CCL4 and CCL8, and the cytokines, IL6, TNF and IL10, were predominantly expressed in macrophages. The transcripts for NPR1, the biologically active ANP receptor, and NPR3, the ANP clearance receptor, as well as PRKG1 (also known as cGKI) and PDE5A, the cyclic GMP-specific phosphodiesterase, were expressed in macrophages and adipocytes. Expression of NPR3 was significantly higher in mature adipocytes (Table 3).

Direct effect of ANP on adipocyte protein secretion

When isolated adipocytes were incubated for 24 h in the presence of ANP, the secretion of leptin (5.6 ± 2.2 vs 2.9 ± 0.8 ng protein/100 mg lipid) and RBP-4 (21.3 ± 9.7 vs 4.2 ± 1.5 ng protein/100 mg lipid) decreased when compared with the control (p < 0.05, n = 3), while that of adiponectin (14.4 ± 3.9 vs 10.5 ± 1.9 ng protein/100 mg lipid) did not statistically change. The secretion rate of IL-6 and GRO-α by adipocytes was lower than for the above-mentioned adipokines and was not affected by ANP treatment (0.30 ± 0.16 vs 0.31 ± 0.12 ng protein/100 mg lipid) and (1.2 ± 0.5 vs 1.0 ± 0.3 ng protein/100 mg lipid), respectively.

Direct effect of ANP on macrophage protein secretion

To demonstrate a direct effect of ANP on adipose tissue macrophages, we measured the secretion of MCP-1, IL-6 and GRO-α by cultured adipose tissue macrophages in the presence or absence of ANP. Incubation of adipose tissue macrophages with ANP resulted in a significant reduction of MCP-1 and IL-6 protein secretion compared with controls (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3). In contrast, GRO-α protein secretion was unaffected when adipose tissue macrophages were treated by ANP.

Effect of HSL inhibition on ANP-induced changes in protein secretion

We performed five additional experiments with adipose tissue pieces to evaluate the effect of HSL inhibition on protein secretion. HSL activity was inhibited using 1 μmol/l of BAY. BAY is a selective inhibitor of HSL with no effect on lipoprotein lipase, adipose triacylglycerol lipase and monoacylglycerol lipase [22]. BAY treatment totally inhibited ANP-induced glycerol release while only partial inhibition of NEFA release into the medium was observed. Glycerol concentrations (μmol/g of tissue) were 2.62 ± 0.31, 4.01 ± 0.354 (p = 0.001 vs control) and 2.82 ± 0.45 (p = 0.007 vs ANP) in control, ANP and ANP+BAY conditions, respectively. NEFA concentrations (μmol/g tissue) were 0.12 ± 0.02, 0.82 ± 0.22 (p = 0.006 vs control) and 0.55 ± 0.14 (p = 0.01 vs ANP) in control, ANP and ANP+BAY conditions, respectively. Interestingly, HSL inhibition reversed ANP-induced inhibition of leptin and GRO-α secretion and increased the secretion of adiponectin (Fig. 4). The results suggest that these factors may be inhibited by metabolic products of lipolysis. The effect of ANP on other cytokines and chemokines was not modified, as shown for IL-6 and RBP-4 (Fig. 4).

Changes in human adipose tissue cytokine secretion (percent of control) in response to ANP treatment in the presence or absence of a selective HSL inhibitor (BAY). Means±SEM of five experiments. a adiponectin; b leptin; c GRO-α; d IL-6; e RBP-4. *p < 0.05 for ANP vs control, † p < 0.05 for ANP vs ANP+BAY

Discussion

The chronic low-grade inflammation associated with obesity is considered to be a major player in the genesis of obesity-associated pathologies. The increased accumulation of macrophages within human adipose tissue itself has been suggested to be an important source of inflammatory products [29, 30]. However, endocrine and nutritional signals capable of modulating adipose tissue inflammation and/or adipokine and cytokine secretion are still not defined. We report here that a physiological concentration of ANP, a major metabolic and cardiovascular hormone known to regulate lipolysis and lipid mobilisation in humans [18], might reduce adipose tissue inflammation through a negative control of the secretion of several adipokines (leptin, RBP-4) and cytokines (IL-6, TNF-α, MCP-1, MIP-1β, GRO-α) with a role evoked in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Importantly, ANP did not affect the secretion of the anti-inflammatory proteins, IL-10 and adiponectin. Thus, the fact that ANP does preserve adiponectin secretion may be relevant, as in a recent study using the same kind of protein array approach, treatment of human adipocytes with gAcrp30 (the globular domain of adiponectin) resulted in 25–50% reduction of the secretion of several cytokines (IL-6, IL-8) and chemokines (GRO-α, MCP-1, MIP-1β) [31]. This suggests that besides adiponectin, ANP may act as a key regulator per se of cytokine secretion in human adipose tissue.

This study examined for the first time the effect of ANP on a wide range of adipose tissue-secreted factors using protein arrays. As adipose tissue-secreted factors can originate from different cell populations and as the ANP lipolytic effect is primate-specific, we decided to work on human adipose tissue pieces to address the question. In cultures of adipose tissue pieces, the in vivo structure of the tissue is partly maintained; it is therefore a suitable model to study regulation at the whole-tissue level. Prior studies have used this model to study lipid metabolism or protein secretion [20, 32]. We have shown that ANP inhibits the secretion of TNF-α, IL-6 and RBP-4. The role of TNF-α and IL-6 in promoting insulin resistance has been widely documented [33, 34]. These pro-inflammatory cytokines have been shown to inhibit insulin signalling in skeletal muscle cells. On the other hand, even though the pro-insulin resistant role of TNF-α in vivo seems well demonstrated [35], this may be still questionable for IL-6, as this cytokine has been shown to increase insulin-stimulated glucose disposal and uptake in lean healthy humans [36]. RBP-4, initially involved in the delivery of retinol to tissues, has recently been suggested as playing a role in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance [37]. A high level of expression of the gene encoding RBP-4 in adipose tissue and a substantial increase in circulating RBP-4 levels in several mouse models of obesity and insulin resistance were reported. Overexpression of RBP-4 or injection of recombinant RBP-4 in normal mice induces insulin resistance, whereas mice with a knockout of the gene encoding RBP-4 show increased insulin sensitivity compared with wild-type mice [12]. Moreover, it was recently shown that serum RBP-4 levels correlated with the magnitude of insulin resistance in obese and diabetic subjects [38]. We report here a regulation of RBP-4 by the cardiovascular hormone ANP in humans. Taken together, the results suggest that ANP, through the negative control of TNF-α, IL-6 and RBP-4 secretion, might also participate in the control of adipose tissue and whole-body insulin sensitivity. This observation is relevant in the field of obesity, type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. It shows interplay between cardiovascular and metabolic complications.

Additionally, ANP decreased the secretion of several chemokines such as MCP-1, GRO-α, MCP-2 and MIP-1β. These factors are known to be involved in inflammatory processes. Weisberg et al. have recently demonstrated the role of MCP-1 and its receptor, the C-C motif chemokine receptor 2, in macrophage recruitment to adipose tissue and development of insulin resistance [39]. ANP also strongly inhibits the release of GRO-α in adipose tissue. GRO-α is a CXC motif chemokine which is involved in inflammation and cell trafficking of various types of leucocytes [40, 41]. Moreover, ANP was shown to reduce leptin production, an observation in agreement with the study of Fain et al. [32]. Leptin has been shown to facilitate the transmigration of labelled monocytes through the endothelium in vitro [27]. Therefore, one can hypothesise that the ANP-mediated inhibition of MCP1, GRO-α and leptin secretion might inhibit the infiltration and activation of adipose tissue macrophages.

To gain insight into the cellular origin of adipose tissue factors regulated by ANP, we isolated adipocytes and macrophages from fresh adipose tissue. Gene expression studies showed that the adipose tissue cytokines and chemokines regulated by ANP were primarily derived from macrophages, in agreement with the study of Curat et al. on human visceral adipose tissue [14]. The adipokines, leptin, adiponectin and RBP-4, were specifically expressed in adipocytes. Adipocytes and macrophages expressed all components of the ANP-signalling pathway. ANP inhibited leptin and RBP-4 secretion from adipocytes and MCP-1 and IL-6 secretion from adipose tissue macrophages. These results suggest that ANP directly modulates the secretory activity of both adipocytes and macrophages in human adipose tissue. Changes in IL-6, TNF-α, leptin and GRO-α protein secretion induced by ANP were not associated with changes in gene expression. A functional role of NP in the immune system has been documented before [42]. ANP has been shown to inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced activation of TNF-α and IL-1β release in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages [43, 44]. Additionally, Kiemer et al. showed both transcriptional and post-translational regulation of TNF-α by ANP in Kupffer cells stimulated with LPS [45]. In conclusion, the ANP signalling pathway modulates the production of inflammatory and insulin resistance-inducing factors in adipocytes and macrophages, probably through post-transcriptional secretory mechanisms.

In addition to a direct effect of ANP on target cells, fatty acids released by adipocytes may act on macrophages. Palmitate, a major NEFA released during lipolysis, has been shown to induce inflammatory changes in RAW264 macrophages [46]. We therefore hypothesised that ANP might also have an impact on macrophage and adipocyte secretions through induction of lipolysis. To test this hypothesis, we measured the effect of ANP on adipose tissue protein secretion under selective HSL inhibition. Pharmacological inhibition of HSL has been shown to inhibit ANP-induced lipolysis in human mature adipocytes [22]. Here we show that lipolysis-derived by-products negatively regulate the secretion of leptin and GRO-α. HSL inhibition increased the secretion of the anti-inflammatory protein adiponectin during ANP treatment. This might suggest that ANP directly stimulates the secretion of adiponectin, an effect being counteracted by lipolysis-derived by-products originating from ANP-induced lipolysis. Accumulation of fatty acids in the culture medium may inhibit adiponectin secretion and hide the stimulatory effect of ANP on its secretion. While fatty acids are obvious candidates for the mediation of the NP effect, it cannot be ruled out that other products of HSL catalytic activity are responsible for the decrease in leptin and GRO-α secretion. HSL hydrolyses cholesterol and retinol esters [47]. As adipose tissue is an important storage depot of vitamin A [48], the release of retinol catalysed by HSL may constitute the first step in signalling pathways involving retinoids. Interestingly, adiponectin and leptin are mainly produced in adipocytes, whereas the main site of production of GRO-α is macrophages. Therefore, lipolysis-derived by-products may act both at an autocrine level in adipocytes and at a paracrine level on macrophages. These data reveal a novel previously unappreciated link between a metabolic pathway, i.e. lipolysis and inflammation.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that a physiological concentration of ANP, through a direct effect on adipocytes and macrophages but also through lipolysis-derived products, inhibits the secretion of several cytokines, chemokines and adipokines involved in leucocyte recruitment and activation as well as in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Therefore ANP may exert an important endocrine function within human adipose tissue to regulate local cytokine production. Changes in ANP plasma levels during physiological states (exercise, water immersion, weightlessness) might be associated with changes in adipose tissue inflammatory status and metabolism. Since physical exercise is known to promote ANP release [49], the inhibitory effect of ANP on the secretion of cytokines and adipokines could be one of the elements contributing to the improvement of insulin resistance in exercising subjects. Conversely, an inverse relationship between BMI and NP plasma levels has been reported [50]. Further studies are required to demonstrate the physiological relevance in vivo of the inhibitory effect of ANP on adipose tissue cytokines production in humans.

Abbreviations

- ADIPOQ:

-

adiponectin

- ANP:

-

atrial natriuretic peptide

- AU:

-

arbitrary unit

- BAY:

-

4-isopropyl-3-methyl-2-([(3S)-3-methylpiperidin-1-yl] carbonyl) isoxazol-5(2H)-one

- CCL2:

-

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CCL4:

-

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 4

- CCL8:

-

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 8

- cGKI:

-

cyclic GMP-dependent protein kinase I

- CXCL1:

-

chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand 1

- GRO:

-

growth-related oncogene

- HSL:

-

hormone-sensitive lipase

- LEP:

-

leptin

- MCP:

-

monocyte chemoattractant protein

- MIP:

-

macrophage inflammatory protein

- NP:

-

natriuretic peptide

- NPR:

-

natriuretic peptide receptor

- PDE5A:

-

phosphodiesterase 5A

- PRKG1:

-

protein kinase, cGMP-dependent, typeI

- qPCR:

-

quantitative PCR

- RANTES:

-

regulated upon activation normally T-expressed and presumably secreted

- RBP-4:

-

retinol-binding protein-4

- TIMP:

-

tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase

References

Festa A, D’Agostino R Jr, Howard G, Mykkanen L, Tracy RP, Haffner SM (2000) Chronic subclinical inflammation as part of the insulin resistance syndrome: the Insulin Resistance Atherosclerosis Study (IRAS). Circulation 102:42–47

Frohlich M, Imhof A, Berg G et al (2000) Association between C-reactive protein and features of the metabolic syndrome: a population-based study. Diabetes Care 23:1835–1839

Pai JK, Pischon T, Ma J et al (2004) Inflammatory markers and the risk of coronary heart disease in men and women. N Engl J Med 351:2599–2610

Ridker PM (2005) C-reactive protein, inflammation, and cardiovascular disease: clinical update. Tex Heart Inst J 32:384–386

Vozarova B, Weyer C, Hanson K, Tataranni PA, Bogardus C, Pratley RE (2001) Circulating interleukin-6 in relation to adiposity, insulin action, and insulin secretion. Obes Res 9:414–417

Haffner SM (2006) The metabolic syndrome: inflammation, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 97:3A–11A

Schindler TH, Cardenas J, Prior JO et al (2006) Relationship between increasing body weight, insulin resistance, inflammation, adipocytokine leptin, and coronary circulatory function. J Am Coll Cardiol 47:1188–1195

Kershaw EE, Flier JS (2004) Adipose tissue as an endocrine organ. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2548–2556

Moller DE (2000) Potential role of TNF-alpha in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Trends Endocrinol Metab 11:212–217

Sartipy P, Loskutoff DJ (2003) Monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in obesity and insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:7265–7270

Maachi M, Pieroni L, Bruckert E et al (2004) Systemic low-grade inflammation is related to both circulating and adipose tissue TNFalpha, leptin and IL-6 levels in obese women. Int J Obes 28:993–997

Yang Q, Graham TE, Mody N et al (2005) Serum retinol binding protein 4 contributes to insulin resistance in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Nature 436:356–362

Cancello R, Henegar C, Viguerie N et al (2005) Reduction of macrophage infiltration and chemoattractant gene expression changes in white adipose tissue of morbidly obese subjects after surgery-induced weight loss. Diabetes 54:2277–2286

Curat CA, Wegner V, Sengenes C et al (2006) Macrophages in human visceral adipose tissue: increased accumulation in obesity and a source of resistin and visfatin. Diabetologia 49:744–747

Cancello R, Tordjman J, Poitou C et al (2006) Increased infiltration of macrophages in omental adipose tissue is associated with marked hepatic lesions in morbid human obesity. Diabetes 55:1554–1561

Potter LR, Abbey-Hosch S, Dickey DM (2006) Natriuretic peptides, their receptors, and cyclic guanosine monophosphate-dependent signaling functions. Endocr Rev 27:47–72

Sengenès C, Berlan M, de Glisezinski I, Lafontan M, Galitzky J (2000) Natriuretic peptides: a new lipolytic pathway in human adipocytes. FASEB J 14:1345–1351

Lafontan M, Moro C, Sengenes C, Galitzky J, Crampes F, Berlan M (2005) An unsuspected metabolic role for atrial natriuretic peptides: the control of lipolysis, lipid mobilization, and systemic nonesterified fatty acids levels in humans. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:2032–2042

Smith U (1971) Morphologic studies of human subcutaneous adipose tissue in vitro. Anat Rec 169:97–104

Fried SK, Russell CD, Grauso NL, Brolin RE (1993) Lipoprotein lipase regulation by insulin and glucocorticoid in subcutaneous and omental adipose tissues of obese women and men. J Clin Invest 92:2191–2198

Lowe DB, Magnuson S, Qi N et al (2004) In vitro SAR of (5-(2H)-isoxazolonyl) ureas, potent inhibitors of hormone-sensitive lipase. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 14:3155–3159

Langin D, Dicker A, Tavernier G et al (2005) Adipocyte lipases and defect of lipolysis in human obesity. Diabetes 54:3190–3197

Schlesinger JB, van Harmelen V, Alberti-Huber CE, Hauner H (2006) Albumin inhibits adipogenesis and stimulates cytokine release from human adipocytes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 291:C27–C33

Xu Y, Kulkosky J, Acheampong E, Nunnari G, Sullivan J, Pomerantz RJ (2004) HIV-1-mediated apoptosis of neuronal cells: Proximal molecular mechanisms of HIV-1-induced encephalopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:7070–7075

Rodbell M (1964) Metabolism of isolated fat cells. Effects of hormones on glucose metabolism and lipolysis. J Biol Chem 29:375–380

Dole VP, Meinertz H (1960) Microdetermination of long-chain fatty acids in plasma and tissues. J Biol Chem 235:2595–2599

Curat CA, Miranville A, Sengenes C et al (2004) From blood monocytes to adipose tissue-resident macrophages: induction of diapedesis by human mature adipocytes. Diabetes 53:1285–1292

Berlan M, Carpene C, Lafontan M, Dang-Tran L (1982) Alpha-2 adrenergic antilipolytic effect in dog fat cells: incidence of obesity and adipose tissue localization. Horm Metab Res 14:257–260

Xu H, Barnes GT, Yang Q et al (2003) Chronic inflammation in fat plays a crucial role in the development of obesity-related insulin resistance. J Clin Invest 112:1821–1830

Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW Jr (2003) Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest 112:1796–1808

Dietze-Schroeder D, Sell H, Uhlig M, Koenen M, Eckel J (2005) Autocrine action of adiponectin on human fat cells prevents the release of insulin resistance-inducing factors. Diabetes 54:2003–2011

Fain J, Kanu A, Bahouth S, Cowan G, Lloyd Hiler M (2003) Inhibition of leptin release by atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) in human adipocytes. Biochem Pharmacol 65:1883–1888

Fantuzzi G (2005) Adipose tissue, adipokines, and inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol 115:911–919, (quiz 920)

Matsuzawa Y (2006) The metabolic syndrome and adipocytokines. FEBS Lett 580:2917–2921

Plomgaard P, Bouzakri K, Krogh-Madsen R, Mittendorfer B, Zierath JR, Pedersen BK (2005) Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces skeletal muscle insulin resistance in healthy human subjects via inhibition of Akt substrate 160 phosphorylation. Diabetes 54:2939–2945

Carey AL, Steinberg GR, Macaulay SL et al (2006) Interleukin-6 increases insulin-stimulated glucose disposal in humans and glucose uptake and fatty acid oxidation in vitro via AMP-activated protein kinase. Diabetes 55:2688–2697

Tamori Y, Sakaue H, Kasuga M (2006) RBP4, an unexpected adipokine. Nat Med 12:30–31, discussion 31

Graham TE, Yang Q, Bluher M et al (2006) Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. N Engl J Med 354:2552–2563

Weisberg SP, Hunter D, Huber R et al (2006) CCR2 modulates inflammatory and metabolic effects of high-fat feeding. J Clin Invest 116:115–124

Becker S, Quay J, Koren HS, Haskill JS (1994) Constitutive and stimulated MCP-1, GRO alpha, beta, and gamma expression in human airway epithelium and bronchoalveolar macrophages. Am J Physiol 266:L278–L286

Jinquan T, Frydenberg J, Mukaida N et al (1995) Recombinant human growth-regulated oncogene-alpha induces T lymphocyte chemotaxis. A process regulated via IL-8 receptors by IFN-gamma, TNF-alpha, IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13. J Immunol 155:5359–5368

Vollmar AM (2005) The role of atrial natriuretic peptide in the immune system. Peptides 26:1086–1094

Kiemer AK, Hartung T, Vollmar AM (2000) cGMP-mediated inhibition of TNF-alpha production by the atrial natriuretic peptide in murine macrophages. J Immunol 165:175–181

Kiemer AK, Vollmar AM (2001) The atrial natriuretic peptide regulates the production of inflammatory mediators in macrophages. Ann Rheum Dis 60(Suppl 3):iii68–iii70

Kiemer AK, Baron A, Gerbes AL, Bilzer M, Vollmar AM (2002) The atrial natriuretic peptide as a regulator of Kupffer cell functions. Shock 17:365–371

Suganami T, Nishida J, Ogawa Y (2005) A paracrine loop between adipocytes and macrophages aggravates inflammatory changes: role of free fatty acids and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 25:2062–2068

Villarroya F, Giralt M, Iglesias R (1999) Retinoids and adipose tissues: metabolism, cell differentiation and gene expression. Int J Obes 23:1–6

Wei S, Lai K, Patel S et al (1997) Retinyl ester hydrolysis and retinol efflux from BFC-1beta adipocytes. J Biol Chem 272:14159–14165

Niessner A, Ziegler S, Slany J, Billensteiner E, Woloszczuk W, Geyer G (2003) Increases in plasma levels of atrial and brain natriuretic peptides after running a marathon: are their effects partly counterbalanced by adrenocortical steroids? Eur J Endocrinol 149:555–559

Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D et al (2004) Impact of obesity on plasma natriuretic peptide levels. Circulation 109:594–600

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the skilled technical assistance and help of M.-A. Marquès, C. Valle and G. Casteran, and to A. Zakaroff-Girard and V. Bourlier for the work on macrophages. This work is part of the project ‘Hepatic and Adipose Tissue in the Metabolic Syndrome’ (HEPADIP, see http://www.hepadip.org/), which is supported by the European Commission as an integrated project under the 6th Framework Program (contract LSHM-CT-2005-018734). C. Moro was supported by a grant from the French Association for the Study of Obesity (AFERO) and Sanofi-Aventis Laboratories.

Duality of interest

The authors have no duality of interest to declare.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moro, C., Klimcakova, E., Lolmède, K. et al. Atrial natriuretic peptide inhibits the production of adipokines and cytokines linked to inflammation and insulin resistance in human subcutaneous adipose tissue. Diabetologia 50, 1038–1047 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-007-0614-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-007-0614-3