Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

We evaluated diabetes-related pregnancy outcomes in a cohort of Spanish women in relation to their glucose tolerance status, prepregnancy BMI and other predictive variables.

Methods

The present paper is part of a prospective study to evaluate the impact of American Diabetes Association (2000) criteria in the Spanish population. A total of 9,270 pregnant women were studied and categorised as follows according to prepregnancy BMI quartiles and glucose tolerance status: (1) negative screenees; (2) false-positive screenees; (3) gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) according to American Diabetes Association criteria only; and (4) GDM according to National Diabetes Data Group criteria (NDDG). We evaluated fetal macrosomia, Caesarean section and seven secondary outcomes as diabetes-related pregnancy outcomes. The population-attributable and population-prevented fractions of predictor variables were calculated after binary logistic regression analysis with multiple predictors.

Results

Both prepregnancy BMI and abnormal glucose tolerance categories were independent predictors of pregnancy outcomes. The upper quartile of BMI accounted for 23% of macrosomia, 9.4% of Caesarean section, 50% of pregnancy-induced hypertension and 17.6% of large-for-gestational-age newborns. In contrast, NDDG GDM accounted for 3.8% of macrosomia, 9.1% of pregnancy-induced hypertension and 3.4% of preterm births.

Conclusions/interpretation

In terms of population impact, prepregnancy maternal BMI exhibits a much stronger influence than abnormal blood glucose tolerance on macrosomia, Caesarean section, pregnancy-induced hypertension and large-for-gestational-age newborns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) increases the risk of adverse complications for both mother and child [1]. The same is true for obesity, for which the risks include higher rates of GDM, hypertension, pre-eclampsia and macrosomia [2–12]. The rate of overweight and obesity has increased steadily around the world over the past 20 years, affecting all age groups and including women of reproductive age [13, 14]. In addition, increased BMI and GDM often occur in the same patient. However, less is known about the relative contributions of maternal overweight and GDM to the increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the independent influence of prepregnancy BMI and glucose tolerance status on the presentation of diabetes-related adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Subjects, materials and methods

This prospective study was conducted in 16 general hospitals of the Spanish National Health Service in 2002 and the research design and methods are reported in [15]. The research was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in 2000 and informed consent was obtained from patients where appropriate. All women with singleton pregnancies and without a former diagnosis of diabetes mellitus were included. Pregnancies with preterm delivery (at less than 28 weeks) and the second pregnancy of women with two pregnancies in the same year were excluded. After a 50 g glucose challenge test (GCT), women who had a venous plasma glucose ≥7.8 mmol/l were scheduled for a diagnostic, 100 g, 3 h OGTT. Criteria of both the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG) (fasting, 5.8 mmol/l; 1 h, 10.6 mmol/l; 2 h, 9.2 mmol/l; 3 h, 8.1 mmol/l) [16] and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) (fasting, 5.3 mmol/l; 1 h, 10 mmol/l; 2 h, 8.6 mmol/l; 3 h, 7.8 mmol/l) [17] were considered. With both criteria, GDM was defined when at least two plasma glucose measurements were equal to or higher than the cut-off points. The term ‘ADA-only GDM’ was used to refer to pregnant women who would be diagnosed with GDM by the ADA but not by the NDDG criteria [18].

Data collected included maternal age, prepregnancy BMI, chronic arterial hypertension, pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) (including pre-eclampsia), gestational age at delivery, delivery characteristics (spontaneous/induced, vaginal/Caesarean section), reason for Caesarean section (elective, dystocia, fetal distress, others) and newborn characteristics (birth weight, sex, Apgar score, perinatal mortality, major congenital malformations). Gestational age was defined as number of completed weeks, based on the last menstrual period or on the earliest ultrasound assessment if discordant. Pregestational weight was self-reported and trained nurses measured height at the first prenatal visit. Chronic hypertension was defined as treated hypertension before pregnancy or arterial blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg in the first 20 weeks of pregnancy.

Macrosomia and Caesarean section were defined as primary outcomes, and the rate of large for gestational age (LGA), preterm birth, PIH, Apgar score<7 at 1 and 5 min, major congenital malformations and perinatal mortality as secondary outcomes. Macrosomia was defined as a birthweight at or above 4 kg. Newborns were defined as LGA when sex-specific birthweight for gestational age was above the 90th percentile of Spanish fetal growth curves [19] and small for gestational age (SGA) when under the 10th percentile. Major congenital malformations were defined as malformations that cause significant functional or cosmetic impairment, require surgery or are life-limiting.

Four glucose tolerance groups were defined [15, 20]: women with GDM according to NDDG criteria receiving usual care (NDDG GDM), and three untreated groups, representing a gradient of carbohydrate tolerance. Negative screenees had a glucose value below 7.8 mmol/l after a 50 g glucose oral challenge (GCT). False-positive screenees had a positive GCT but a negative OGTT by ADA criteria and did not receive specific treatment [17]. As described before, women with ADA-only GDM were those women that would be diagnosed with GDM by ADA but not by NDDG criteria. BMI was categorised in quartiles (quartile 1, <21.5 kg/m2; quartile 2, 21.5–23.6 kg/m2; quartile 3, 23.7–26.1 kg/m2; quartile 4, >26.1 kg/m2).

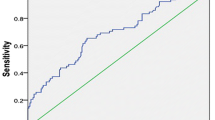

Binary logistic regression analysis with multiple predictors with a backward method was used to calculate adjusted odds ratios (OR) for developing complications and 95% CIs. All potentially predictive variables (glucose tolerance category, prepregnancy BMI quartiles, fetal sex, maternal age, gestational age at delivery, macrosomia and PIH in current pregnancy) were fed in to the models when applicable (i.e. macrosomia was not included as a potential predictor of LGA). The stopping criterion was set at a p value of ≥0.10.

We calculated the population-attributable fraction (AFp) for risk factors and the prevented fraction in the population (PFp) for protective factors [21]. AFp is defined as the excess number of cases resulting from an exposure divided by the total number of cases in a defined population, and is calculated as:

PFp is defined as the number of cases prevented in the population resulting from an exposure to a protective factor and is calculated as:

Results

A total of 9,270 pregnant women were included. Table 1 summarises maternal, pregnancy and delivery characteristics. Table 2 shows the predictive models for macrosomia, Caesarean section, PIH, preterm birth, LGA and Apgar 1 min <7. The upper quartile of BMI accounted for 23% of macrosomia, 9.4% of Caesarean sections, 50% of PIH and 17.6% of LGA. In contrast, NDDG GDM accounted for 3.8% of macrosomia, 9.1% of PIH and 3.4% of preterm births. Fetal sex contributed to the prediction of macrosomia and LGA, maternal age to that of Caesarean section and macrosomia to that of Apgar score 1 min <7. Additional variables were retained by the models, although with borderline significance (Table 2). No significant predictors were found for major congenital malformations, Apgar 5 min <7 or perinatal mortality.

To explore further the role of BMI and GDM in the prediction of outcome variables, we investigated the OR and AFp of overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2) and gestational diabetes mellitus (NDDG GDM) both alone and in combination. This analytical model considered four groups: group 1, non-overweight women without NDDG GDM; group 2, non-overweight women with NDDG GDM; group 3, overweight women without NDDG GDM; and group 4, overweight women with NDDG GDM. Results are displayed in Table 3. Overweight women, both with and without GDM, had significantly higher ORs for macrosomia, Caesarean section, LGA and PIH, whereas non-overweight women with NDDG GDM did not. Furthermore, as overweight women without NDDG GDM formed the more prevalent category, differences among groups turned out to be more apparent when expressed in terms of AFp: the highest AFp of macrosomia, Caesarean section, LGA and PIH corresponded to the overweight non-GDM group, preterm birth being the only exception.

Discussion

There is ample consensus that GDM and obesity/overweight have a negative effect on pregnancy outcome [2–12]. However, few studies have attempted to discern the relative influences of overweight and GDM [22–27]. Obesity and hyperglycaemia have been reported to be independent predictors of different obstetric and perinatal complications, but obesity was a stronger risk factor for macrosomia, Caesarean section and hypertension than hyperglycaemia [24–27]. Glucose tolerance status, and especially obesity, acted in a dose-dependent manner, increasing the risk of perinatal complications as glucose intolerance and BMI increased. Glucose intolerance or obesity was not significantly associated with PIH or macrosomia in an Australian cohort [22]. The present study, partially reported in [15], identifies pregestational BMI and abnormal glucose tolerance categories as independent predictors of perinatal outcome with similar ORs for abnormal glucose tolerance categories and upper BMI quartiles. In addition, it is important to note that upper BMI quartiles in this study do not represent extreme obesity; in fact, the cut-off for the fourth quartile is close to that of overweight.

AFPs and PFp represent the proportion of an adverse outcome that can be attributed to or is prevented by exposure to a given predictor. This differs from the concept of OR, which indicates how much more often an outcome occurs in those with or without a given predictive variable. The rationale for reporting the AFp and PFp values, as opposed to ORs, is that the former take into account both the prevalence and the OR of a given factor. However, the AFp values were calculated only in the two most recently published studies, one dealing with Caesarean section [26] and the other with macrosomia [27].

Analysis of AFp and PFp data sheds a different light on the relevance of predictors. Male sex, for example, increased the risk for macrosomia by a factor of 2.52, but in terms of AFp it accounted for 42.0% of the macrosomia in the population. This figure is important in understanding the contribution of fetal sex to macrosomia, but it is a non-modifiable predictor. In contrast, abnormal glucose tolerance categories and BMI quartiles are modifiable predictors and AFp identifies them, especially BMI, as the most relevant. We would also like to highlight that the upper BMI quartile has a much greater impact on PIH, macrosomia and LGA than quartiles 2 and 3. For instance, 23% of the macrosomia in the population could be attributed to the upper BMI quartile, 6.3% to the third and 7.5% to the second, while only 3.8% could be attributed to NDDG GDM. Even if we consider that women who met the NDDG criteria had received treatment and that the real figure of macrosomia attributable to NDDG GDM is somewhat higher, it is clear that, in this population, maternal BMI is much more relevant than glucose tolerance categories for the prediction (and potential prevention) of macrosomia. Again, we want to highlight that the ORs for macrosomia of BMI quartiles were quite similar to those of glucose tolerance categories; the reason that maternal BMI is so relevant in terms of population risk is the prevalence of each category (25% for each quartile higher than 1) compared with those of abnormal glucose tolerance (19.8, 2.8 and 8.8% for false-positive screenees, ADA-only GDM and NDDG GDM respectively) (Table 2). The findings were similar for the other outcomes: the upper quartile of BMI accounted for 9.4% of Caesarean section, 50% of PIH and 17.6% of LGA in the population while the respective figures for NDDG GDM were 9.1% of PIH and 1% of LGA, and accounted for 3.4% of preterm births.

PIH was associated with a lower risk of macrosomia and LGA. Both chronic hypertension [28] and pre-eclampsia [29] are related to fetal growth retardation, which is attributed to placental anomalies. In addition, elective delivery in pregnancies complicated with PIH could contribute to a decreased rate of macrosomia through a shortened pregnancy.

To confirm the role of BMI and glucose tolerance in the prediction of outcome variables, we explored the ORs and AFp of overweight and NDDG GDM, both alone and combined. This approach identified higher ORs for overweight women, both with and without GDM, and distinctly higher AFp values for overweight women without GDM, further confirming the relevance of BMI for the analysed outcomes.

Our findings of low AFp for glucose tolerance categories are in agreement with a previous study [30] which described low AFp of GDM (defined according to ADA or the World Health Organization) for macrosomia and PIH. Similarly, the AFp of the fourth BMI in the present study for LGA and macrosomia (17.6 and 23.0%) are in agreement with another report for obesity (defined as BMI >29.0 kg/m2) in the period 1995–1999 (19.1 and 25.7%) [7]. However, if we refer to a recent paper [27], our findings are difficult to reconcile. These authors describe very low attributable fractions of LGA from overweight and obesity (0.5 and 1.3%, respectively), and this could come from the possibility that AFp had been calculated from ORs where the reference category was not the unit.

Pregnancy complications related to maternal overweight and obesity are expected to increase in parallel with the rising prevalence of excess maternal weight. Lu and colleagues have already reported that the increasing prevalence of maternal obesity, along with the increased relative risks of adverse perinatal outcome for obese women, has led to a dramatic increase in the AFp values of obesity-related pregnancy complications in recent years [7]. Identification of overweight/obesity as a major determinant of perinatal outcome in population terms should lead to preventive efforts prior to conception and also during pregnancy. However, guidelines for overweight and obesity in pregnancy women are lacking, in contrast with gestational diabetes mellitus.

Our study is unique in that it encompasses both a large Spanish population and prospectively collected information on both BMI and glucose tolerance categories among other variables. As information was collected in university hospitals, the representativeness of the study could be questioned. However, we consider it is acceptable since perinatal outcomes in the current study were reasonably similar to those of the National Perinatal Database for the same year [31]. A limitation of this study is that prediction of macrosomia and Caesarean section could have been more accurate if macrosomia during a previous pregnancy and pregnancy weight gain had been included as predictors of the former and prior Caesarean section as a predictor of the latter. Furthermore, other pregnancy-related predictors, such as previous parity, were not taken into account. Nevertheless, the relative importances of prepregnancy BMI and abnormal glucose tolerance are unquestionable.

In conclusion, in the Spanish population, both prepregnancy maternal BMI and gestational hyperglycaemia are independent risk factors for diabetes-related adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, prepregnancy BMI has a much stronger population impact than abnormal glucose tolerance categories, due to its higher prevalence. This is especially the case for PIH, macrosomia, LGA and Caesarean section.

Collaborators Additional members of the Spanish Group for the study of the impact of Carpenter and Coustan GDM thresholds: C. Bach (Girona, Spain), M. García (Girona, Spain); M. D. Maldonado (Toledo, Spain), O. Rodriguez (Toledo, Spain), I. Díaz (Toledo, Spain), O. Gutiérrez (Toledo, Spain), A. Carazo (Toledo, Spain), M. Martín (Toledo, Spain); M. Navarro (Granada, Spain), P. Velasco (Granada, Spain), J. Sancho-Miñano (Granada, Spain); L. Blesa (Zaragoza, Spain), M. Sánchez-Dehesa (Zaragoza, Spain), E. Faure (Zaragoza, Spain); M. N. Suáre (Tenerife, Spain); A. Santcalpe (Terrassa, Spain); I. Rodriguez (Vigo, Spain); J. C. Martínez (Alicante, Spain), S. Regel (Alicante, Spain), A. Picó (Alicante, Spain); W. Plasencia (Las Palmas, Spain), R. García (Las Palmas, Spain); T. Montoya (Getafe, Spain), S. Monereo (Getafe, Spain); P. Martín-Vaquero (Madrid, Spain), L. Herranz (Madrid, Spain), M. Jañez (Madrid, Spain), M. J. Delgado (Madrid, Spain); I. Mascarell (Valencia, Spain), P. Cubells (Valencia, Spain), R. Casañ (Valencia, Spain), R. Gironés (Valencia, Spain); J. M. Adelantado (Barcelona, Spain), G. Ginovart (Barcelona, Spain).

Abbreviations

- ADA:

-

American Diabetes Association

- AFp:

-

population-attributable fraction

- GCT:

-

glucose challenge test

- GDM:

-

gestational diabetes mellitus

- LGA:

-

large for gestational age

- NDDG:

-

National Diabetes Data Group

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- PFp:

-

prevention fraction in the population

- PIH:

-

pregnancy-induced hypertension

- SGA:

-

small for gestational age

References

Metzger BE (1991) Summary and recommendations of the Third International Workshop–Conference on Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes 40(Suppl 2):197–201

Garbaciack JA, Richter M, Miller S, Barton JJ (1985) Maternal weight and pregnancy complications. Am J Obstet Gynecol 152:238–245

Witter FR, Caufield LE, Stolzfus RJ (1995) Influence of maternal anthropometric status and birth weight on the risk of Caesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 85:947–951

Crane SS, Wojtowycz MA, Dye TD, Aubry RH, Artal R (1997) Association between pre-pregnancy obesity and the risk of Cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol 89:213–216

Brost BC, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM et al (1997) The preterm prediction study: associations of Cesarean delivery with increases in maternal weight and body mass index. Am J Obstet Gynecol 177:333–341

Cnattingius S, Bergstrom R, Lipworth L, Kramer MS (1998) Prepregnancy weight and the risk of adverse outcomes. N Engl J Med 338:147–152

Lu GC, Rouse DJ, DuBard M, Cliver S, Kimberlin D, Hauth JC (2001) The effect of the increasing prevalence of maternal obesity on perinatal morbidity. Am J Obstet Gynecol 185:845–849

O’Brien TE, Ray JG, Chan WS (2003) Maternal body mass index and the risk of preeclampsia: a systematic overview. Epidemiology 14:368–374

Jensen DM, Damm P, Sorensen B et al (2003) Pregnancy outcome and prepregnancy body mass index in 2459 glucose-tolerant Danish women. Am J Obstet Gynecol 189:239–244

Sheiner E, Levy A, Menes TS, Silverberg D, Katz M, Mazor M (2004) Maternal obesity as an independent risk factor for Caesarean delivery. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 18:196–201

Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D et al (2004) Obesity, obstetric complications and Cesarean delivery-rate—a population-based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol 190:1091–1097

Linné Y (2004) Effects of obesity on women’s reproduction and complications during pregnancy. Obesity Rev 5:137–143

World Health Organization (2000) Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic. Report of a WHO consultation. WHO Tech Rep Ser 894:i–xii:1–253

Kopelman PG (2000) Obesity as a medical problem. Nature 404:635–643

Ricart W, López J, Mozas J et al (2005) Potential impact of American Diabetes Association (2000) criteria for diagnosis of gestational diabetes mellitus in Spain. Diabetologia 48:1135–1141

National Diabetes Data Group (1979) Classification and diagnosis of diabetes mellitus and other categories of glucose intolerance. Diabetes 28:1039–1057

Carpenter MW, Coustan DR (1982) Criteria for screening tests for gestational diabetes. Am J Obstet Gynecol 144:768–773

Schwartz ML, Ray WN, Lubarsky SL (1999) The diagnosis and classification of gestational diabetes mellitus: is it time to change our tune? Am J Obstet Gynecol 180:1560–1571

Santamaria Lozano R, Verdú Martín L, Martín-Caballero C, García López G (1998) Tablas españolas de pesos neonatales según edad gestacional. Ed Artes Gráficas Beatulo, Badalona

Magee MS, Walden CE, Benedetti TJ, Knopp RH (1993) Influence of diagnostic criteria on the incidence of gestational diabetes and perinatal morbidity. JAMA 269:609–615

Miettinen O (1974) Proportion of disease caused or prevented by a given exposure, trait or intervention. Am J Epidemiol 99:325–332

van Hoorn J, Dekker G, Jeffries B (2002) Gestational diabetes versus obesity as risk factors for pregnancy-induced hypertensive disorders and fetal macrosomia. Aust NZ J Obstet Gynaecol 42:35–40

Schaefer U, Heuer R, Kilavuz O, Pandura A, Henrich W, Vetter K (2002) Maternal obesity not maternal glucose values correlates best with high rates of fetal macrosomia in pregnancies complicated by gestational diabetes. J Perinat Med 30:313–321

Brill Y, Windrim R (2003) Vaginal birth after Caesarean section: review of antenatal predictors of success. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 25:275–286

Bo S, Menato G, Signorile A et al (2003) Obesity or diabetes: what is worse for the mother and for the baby? Diabetes Metab 29:175–178

Ehrenberg HM, Durnwald CP, Catalano P, Mercer BM (2004) The influence of obesity and diabetes on the risk of Cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:969–974

Ehrenberg HM, Mercer BM, Catalano PM (2004) The influence of obesity and diabetes on the prevalence of macrosomia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 191:964–968

Lydakis C, Beevers DG, Beevers M, Lip GY (1998) Obstetric and neonatal outcome following chronic hypertension in pregnancy among different ethnic groups. Q J Med 91:837–844

Odegard RA, Vatten LJ, Nilsen ST, Salvesen KA, Austgulen R (2000) Preeclampsia and fetal growth. Obstet Gynecol 96:950–955

Schmidt MI, Duncan BB, Reichelt AJ et al (2001) Gestational diabetes mellitus diagnosed with a 2-h 75-g oral glucose tolerance test and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care 24:1151–1155

González NL, Medina V, Martinez J (2004) Base de datos perinatales nacionales del año 2002. Prog Obstet Gynaecol 47:168–567

Acknowledgements

This work was sponsored by an unrestricted grant from Lilly Laboratories in Spain and supported by the Catalan Association of Diabetes, the Catalan Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, the Spanish Society of Diabetes and the Spanish Society of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. It was also supported by research grants from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (RCMN C03/08, RGDM G03/212, RGTO G03/028). The views expressed in the article are those of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ricart, W., López, J., Mozas, J. et al. Body mass index has a greater impact on pregnancy outcomes than gestational hyperglycaemia. Diabetologia 48, 1736–1742 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-1877-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-005-1877-1