Abstract

In Western countries, chronic coronary artery disease (CAD) has a prevalence of 3–4%. The aims of treatment of chronic CAD are

(1) improvement of quality of life by preventing anginal pain, by maintaining exercise capability, and by reducing anxiety;

(2) decrease of cardiovascular morbidity, especially by avoiding myocardial infarction and development of heart failure;

(3) reduction of mortality.

These goals can be achieved by

(a) cardiovascular risk reduction, especially management of risk factors,

(b) optimal medical therapy,

(c) coronary revascularization,

(d) periods of rehabilitation, and

(e) outpatient long-term observation and treatment.

The patient has a good chance to improve the natural course of his disease by changing his lifestyle. In this regard, physical exercise, weight reduction and smoking cessation have to be mentioned first. Furthermore, the cardiovascular risk may significantly be diminished by adequate treatment of hyperlipoproteinemia: lowering of plasma LDL cholesterol levels in patients with chronic CAD is associated with a retarded progression of atherosclerosis as well as a decrease of cardiovascular events by 30–40% and lower mortality (by up to 34%). In patients with CAD and/or type 2 diabetes, statin therapy leads to a significant improvement of prognosis independent of the basal value of LDL cholesterol. Improved diet and adequate medical therapy may also result in diminished cardiovascular risk. By means of physical activity, mortality and morbidity of CAD can also be significantly reduced.

The antianginal medication in patients with chronic CAD consists of nitrates, β-blockers, and calcium channel blockers. In order to prevent myocardial infarction and death (secondary prevention), antiplatelet agents, renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system blockers, as well as cholesterol-lowering drugs are applied. In this paper, the guidelines of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association, the European Society of Cardiology and the NVL-KHK (German) guidelines regarding prevention, medical therapy and coronary artery revascularization procedures are summarized.

Do the guidelines reflect daily practice? To answer this question, the following topics are discussed:

(1) Management of risk factors with respect to available guidelines,

(2) missing evidence from randomized controlled trials for medical therapy options widely used in clinical practice,

(3) guideline-compliant use or underuse of diagnostic assessment, medical therapy and revascularization procedures,

(4) gender bias in indications for percutaneous coronary interventions and in the use of investigations/evidence-based medical therapy, and

(5) nonadherence to existing guidelines.

Zusammenfassung

Die chronische koronare Herzkrankheit (KHK, stabile Angina pectoris) hat in den westlichen Industrienationen eine Prävalenz von 3–4%. Die Ziele der Behandlung der chronischen KHK sind

1. Steigerung der krankheitsbezogenen Lebensqualität, u.a. durch Vermeidung von Angina-pectoris-Beschwerden, Erhalt der Belastungsfähigkeit und Verminderung von psychischen Erkrankungen (Depression, Angststörungen), die mit der KHK assoziiert sind;

2. Reduktion der kardiovaskulären Morbidität, insbesondere durch Vermeidung von Myokardinfarkten und der Entwicklung einer Herzinsuffizienz;

3. Reduktion der Sterblichkeit.

Diese Ziele können durch

a) Risikofaktorenmanagement (Hyperlipoproteinämien, arterielle Hypertonie, Diabetes mellitus und Übergewicht) und Prävention,

b) optimale medikamentöse Therapie und

c) Revaskularisationstherapie (perkutane Koronarintervention oder aortokoronare Bypassoperation),

d) Rehabilitationsmaßnahmen und

e) hausärztliche Langzeitbetreuung erreicht werden.

Der Patient hat durch Umstellung seines Lebensstils die Möglichkeit, den weiteren Verlauf seiner Erkrankung selbst positiv zu beeinflussen. Die nichtmedikapamentösen Therapiemöglichkeiten bilden die Grundlage des Risikofaktorenmanagements: Hierzu gehören in erster Linie körperliches Training, Gewichts reduktion und Nikotinabstinenz. Des Weiteren kann durch adäquate Behandlung einer Hyperlipoproteinämie, in erster Linie einer Hypercholesterinämie mit deutlich erhöhtem LDL- und niedrigem HDL-Cholesterin, ferner eines Diabetes mellitus und einer arteriellen Hypertonie das kardiovaskuläre Risiko gesenkt werden. Eine deutliche Senkung des LDL-Cholesterins bei Koronarkranken ist mit einer Verlangsamung der Progression der Atherosklerose sowie mit einer Abnahme der Anzahl kardiovaskulärer Ereignisse um 30–40% sowie mit einer um bis zu 34% niedrigeren Mortalität vergesellschaftet. Bei Koronarkranken und bei Patienten mit Diabetes mellitus Typ 2 lässt sich durch Statine eine signifikante Verbesserung der Prognose unabhängig vom LDL-Cholesterin-Ausgangswert erreichen. Eine an ungesättigten Fettsäuren reiche Kost und eine adäquate medikamentöse Therapie können ebenso das kardiovaskuläre Risiko vermindern. Auch durch körperliches Training (15–60 min, 5–7 Tage/Woche) können Mortalität und Morbidität der KHK signifikant reduziert werden.

Die durch Leitlinien gestützte antianginöse Therapie bei Patienten mit chronischer, stabiler KHK besteht aus Nitraten, β-Rezeptoren-Blockern und Calciumantagonisten. Zur Sekundärprävention werden Thrombozytenaggregationshemmer (Acetylsalicylsäure, Clopidogrel), Inhibitoren des Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosteron-Systems (ACE-Hemmer, Angiotensin-II-Rezeptoren-Blocker und Aldosteronrezeptorantagonisten) sowie cholesterinsenkende Substanzen (in erster Linie Statine) verwendet. In dieser Arbeit sind die ACC/AHA-(American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association) und ESC-Leitlinen (European Society of Cardiology) sowie die nationalen Versorgungsleitlinien der chronischen KHK (NVL-KHK) hinsichtlich Sekundärprävention, medikamentöser Therapie und Revaskularisationsmaßnahmen (perkutane Koronarintervention bzw. aortokoronare Bypassoperation) zusammengefasst.

Geben diese Leitlinien den Alltag wieder? Zur Beantwortung dieser Frage werden fünf Gesichtspunkte diskutiert:

1. Management der Risikofaktoren, Sekundärprävention vor dem Hintergrund der verfügbaren Leitlinien,

2. fehlende Evidenz aus randomisierten, kontrollierten Studien für medikamentöse Therapieoptionen, die in der klinischen Praxis weitverbreitet sind,

3. mit den Leitlinien konforme oder zu geringe Anwendung diagnostischer Verfahren, medikamentöser Therapie und perkutaner interventioneller bzw. chirurgischer Revaskularisationsmaßnahmen (EUROASPIRE- und Euro-Heart-Survey-Programme),

4. Benachteiligung der Frauen bei der KHK-Diagnostik, bei der Indikationsstellung perkutaner koronarer Interventionen sowie bei evidenzbasierter medikamentöser Therapie und

5. Nichtbefolgung der existierenden Leitlinien der großen internationalen Fachgesellschaften.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

NVL: Nationale Versorgungsleitlinien. Chronische KHK, Kurzfassung. Träger Bundesärztekammer, Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften, Kassenärztliche Bundesvereinigung, April 2008.

Gibbons RJ, Chatterjee K, Daley J, et al. ACC/AHA/ACP-ASIM guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina). J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;33:2092–197.

Gibbons RJ, Abrams J, Chatterjee K, et al. ACC/AHA 2002 guideline update for the management of patients with chronic stable angina - summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on the Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina). Circulation 2003;107:149–58.

Fraker TDJr, Fihn SD, writing on behalf of the 2002 Chronic Stable Angina Writing Committee, 2002 Writing Committee Members, et al. 2007 chronic angina focused update of the ACC/AHA 2002 guidelines for the management of patients with chronic stable angina: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Writing Group to Develop the Focused Update of the 2002 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Chronic Stable Angina. Circulation 2007;116:2762–72.

Authors/Task Force Members, Fox K, Garcia MAA, Ardissino D, et al. Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: the Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1341–81.

Dietz R, Rauch B. Leitlinien zur Diagnose und Behandlung der chronischen koronaren Herzerkrankung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Kardiologie — Herz- und Kreislauffor schung (DGK). Z Kardiol 2003;92:501–21.

Smith GD, Shipley MJ, Marmot MG, et al. Plasma cholesterol concentration and mortality. The Whitehall Study. JAMA 1992;267:70–6.

Brown G, Albers JJ, Fisher LD, et al. Regression of coronary artery disease as a result of intensive lipid-lowering therapy in men with high levels of apolipoprotein B. N Engl J Med 1990;323:1289–98.

La Rosa JC, He J, Vupputuri S. Effect of statins on risk of coronary disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA 1999;282:2340–6.

Hokanson JE, Austin MA. Plasma triglyceride level is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease independent of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol level: a meta-analysis of population-based prospective studies. J Cardiovasc Risk 1996;3: 213–9.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. MRC/BHF Heart Protection Study of cholesterol lowering with simvastatin in 20536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2002;360:7–22.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care for patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 2003;26:Suppl 1:s33–50.

Gaede P, Vedel P, Larsen N, et al. Multifactorial intervention and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2003;348:383–93.

Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (Prospective Pioglitazone Clinical Trial in Macrovascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2005;366:1279–89.

Authors/Task Force Members, Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, et al. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007;25:1105–87.

Haskell WL, Alderman EL, Fair JM, et al. Effects of intensive multiple risk factor reduction on coronary atherosclerosis and clinical cardiac events in men and women with coronary artery disease. The Stanford Coronary Risk Intervention Project (SCRIP). Circulation 1994;89:975–90.

Schuler G, Hambrecht R, Schlierf G, et al. Regular physical exercise and low-fat diet. Effects on progression of coronary artery disease. Circulation 1992;86:1–11.

Hermanson B, Omenn GS, Kronmal RA, et al. Beneficial six-year outcome of smoking cessation in older men and women with coronary artery disease. Results from the CASS registry. N Engl J Med 1988;319:1365–9.

He K, Song Y, Daviglus ML, et al. Accumulated evidence on fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality: a metaanalysis of cohort studies. Circulation 2004;109:2705–11.

Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto Miocardico. Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Lancet 1999;354:447–55.

Tillmanns H, Neumann FJ, Parekh N, et al. Pharmacologic effects on coronary microvessels during myocardial ischaemia. Eur Heart J 1990;11:Suppl B:10–5.

Tillmanns H, Neumann FJ, Parekh N, et al. Calcium antagonists and myocardial microperfusion. Drugs 1991;42:Suppl 1:1–6.

Azevedo ER, Schofield AM, Kelly S, et al. Nitroglycerin withdrawal increases endothelium-dependent vasomotor response to acetylcholine. J Am Coll Cardiol 2001;37:505–9.

Münzel T, Daiber A, Mülsch A. Explaining the phenomenon of nitrate tolerance. Circ Res 2005;97:618–28.

Yusuf S, Peto R, Bennett D, et al. Early intravenous atenolol treatment in suspected acute myocardial infarction: preliminary report of a randomised trial. Lancet 1980;316:273–6.

Fox K, Borer JS, Camm AJ, et al., for the Heart Rate Working Group. Resting heart rate in cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;50:823–30.

Fox K, Ferrari R, Tendera M, et al. Rationale and design of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of ivabradine in patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction: the Morbidity-Mortality Evaluation of the If Inhibitor Ivabradine in Patients with Stable Coronary Artery Disease and Left Ventricular Systolic Dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL) Study. Am Heart J 2006;152:860–6.

Fox K, Ford J, Steg PC, et al. Ivabradine for patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular systolic dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2008;372:807–16.

Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative overview of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy — I: Prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke by prolonged antiplatelet therapy in various categories of patients. BMJ 1994;308:81–106.

CAPRIE Steering Committee. A randomised, blinded trial of clopidogrel versus aspirin in patients at risk of ischaemic events (CAPRIE). Lancet 1996;348:1329–39.

Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, et al. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:145–53.

Fox MK. Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study). Lancet 2003;362:782–8.

Messerli FH, Mancia G, Conti CR, et al. Dogma disputed: Can aggressively lowering blood pressure in hypertensive patients with coronary artery disease be dangerous? Ann Intern Med 2006;144:884–93.

The ONTARGET Investigators. Telmisartan, ramipril or both in patients at high risk for vascular events. N Engl J Med 2008;358:1547–59.

Nissen SE, Tuzcu EM, Schönhagen P, et al. Effect of intensive compared with moderate lipid-lowering therapy on progression of coronary atherosclerosis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291:1071–80.

Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Sipahi I, et al., ASTEROID Investigators. Effect of very high-intensity statin therapy on regression of coronary atherosclerosis. The ASTEROID Trial. JAMA 2006;295:1556–65.

Campeau L. Grading of angina pectoris [Letter]. Circulation 1976;54:522–3.

Eagle KA, Guyton RA, Davidoff R, et al., American College of Cardiology, American Heart Association. ACC/AHA 2004 guideline update for coronary artery bypass graft surgery: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Update the 1999 Guidelines for Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery) [Erratum in: Circulation 2005;111: 2014]. Circulation 2004;110:e340–437.

Yusuf S, Zucker D, Passamani E, et al. Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Trialists’ Collaboration. Lancet 1994;344:563–70.

Caracciolo EA, Davis KB, Sopkp G, et al. Comparison of surgical and medical group survival in patients with left main equivalent coronary artery disease: longterm CASS experience. Circulation 1995;91:2335–44.

Bucher, HC, Hengstler P, Schindler C, et al. Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty versus medical treatment for non-acute coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2000;321:73–7.

Boden WE, O’Rouske RA, Teo KK, for the COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med 2007;356:1503–16.

Prasad A, Rihal C, Holmes DRJr. The COURAGE trial in perspective. Cathet Cardiovasc Interv 2008;72:54–9.

Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation 2008;117:1283–91.

Silber S, Albertsson P, Aviles FF, et al. Guidelines for percutaneous coronary interventions. The Task Force for Percutaneous Coronary Interventions of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2005;26:804–47.

Hoffman SN, Ten Brook JAJr, Wolf MP. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing coronary artery bypass graft with percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty: one- to eight-year outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:1293–304.

EUROASPIRE II Study Group. Lifestyle and risk factor management and use of drug therapies in coronary patients from 15 countries. Eur Heart J 2001:22:554–72.

EUROASPIRE I and II Group. Clinical reality of coronary prevention guidelines: a comparison of EUROASPIRE I and II in nine countries. Lancet 2001;357:995–1001.

Anselmino M, Bartnik M, Malmberg K, et al., on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. Management of coronary artery disease in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Acute management reasonable but secondary prevention unacceptably poor: a report from the Euro Heart Survey on Diabetes and the Heart. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil 2007;14:28–36.

Coats AJS. Chronic stable angina and its treatment: why Cinderella never gets to the ball? Int J Cardiol 2000;76:97–9.

CASS Principal Investigators and their Associates. Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS): a randomised trial of coronary artery bypass surgery. Survival data. Circulation 1983;68:939–50.

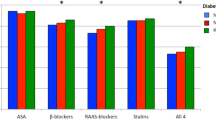

Daly C, Clemens F, Lopez-Sendon JL, et al., on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. The impact of guideline compliant medical therapy on clinical outcome in patients with stable angina: findings from the Euro Heart Survey of Stable Angina. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1298–304.

Daly C, Clemens F, Lopez-Sendon JL, et al., on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. The clinical characteristics and investigations planned in patients with stable angina presenting to cardiologists in Europe: from the Euro Heart Survey of Stable Angina. Eur Heart J 2005;26:996–1010.

Daly CA, Clemens F, Lopez-Sendon JL, et al., on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. The initial management of stable angina in Europe, from the Euro Heart Survey. A description of pharmacological management and revascularization strategies initiated within the first month of presentation to a cardiologist in the Euro Heart Survey of Stable Angina. Eur Heart J 2005;26:1011–22.

Breeman A, Hordijk-Trion M, Lenzen M, et al., on behalf of the Investigators of the Euro Heart Survey on Coronary Revascularization. Treatment decisions in stable coronary artery disease: insights from the Euro Heart Survey on Coronary Revascularization. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006;132:1001–9.

Ayanian JZ, Epstein AM. Differences in the use of procedures between woman and men hospitalized for coronary heart disease. N Eng J Med 1991;325:221–5.

Steingart RM, Packer M, Hamm P, et al., for the Survival and Ventricular Enlargement Investigators. Sex differences in the management of coronary artery disease. N Engl Med 1991;325:226–30.

Tobin JN, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Wexler JP, et al. Sex bias in considering coronary bypass surgery. Ann Intern Med 1987; 107:19–25.

Tillmanns H, Waas W, Voss R, et al. Gender differences in the outcome of cardiac interventions. Herz 2005;30:375–89.

Daly C, Clemens B, Lopez Sendon, et al., on behalf of the Euro Heart Survey Investigators. Gender differences in the management and clinical outcome of stable angina. Circulation 2006;113:490–8.

Gislason GH, Abildstrom SZ, Rasmussen JN, et al. Nationwide trends in the prescription of beta-blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors after myocardial infarction in Denmark, 1995–2002. Scand Cardiovasc J 2005; 39:42–9.

Ho PM, Magid DJ, Masaudi FA, et al. Adherence to cardioprotective mediacations and mortality among patients with diabetes and ischemic heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2006;6:48.

Newby LK, LaPointe NMA, Chen AY, et al. Long-term adherence to evidence-based secondary prevention therapies in coronary artery disease. Circulation 2006;113:203–12.

Ho PM, Magid DJ, Shetterly SM, et al. Medication non-adherence is associated with a broad range of adverse outcomes in patients with coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 2008;155:772–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tillmanns, H., Erdogan, A. & Sedding, D. Treatment of Chronic CAD – Do the Guidelines (ESC, AHA) Reflect Daily Practice?. Herz 34, 39–54 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-009-3209-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00059-009-3209-6

Key Words:

- Chronic stable coronary artery disease

- NVL-KHK, ACC/AHA and ESC guidelines

- Percutaneous coronary interventions

- Coronary artery bypass graft surgery

- Underuse of available guidelines