Abstract

Aim

To investigate the long-term (≥15 years) benefit of orthodontic Class II treatment (Tx) on oral health (OH).

Subjects and methods

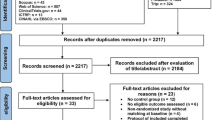

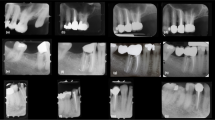

All patients (Department of Orthodontics, University of Giessen, Giessen, Germany) who underwent Class II correction (Herbst-multibracket Tx, end of active Tx ≥ 15 years ago) and agreed to participate in a recall (clinical examination, interview, impressions, and photographs) were included. Records after active Tx were used to assess the long-term OH effects. Data were compared to corresponding population-representative age-cohorts as well as to untreated Class I controls without orthodontic Tx need during adolescence.

Results

Of 152 treated Class II patients, 75 could be located and agreed to participate at 33.7 ± 3.0 years of age (pre-Tx age: 14.0 ± 2.7 years). The majority (70.8%) were fully satisfied with their teeth and with their masticatory system. The Decayed, Missing, Filled Teeth Index (DMFT) was 7.1 ± 4.8 and, thus, almost identical to that of the untreated Class I controls (7.9 ± 3.6). In contrast, the DMFT in the population-representative age-cohort was 56% higher. The determined mean Community Periodontal Index (CPI) maximum score (1.6 ± 0.6) was also comparable to the untreated Class I controls (1.7 ± 0.9) but in the corresponding population-representative age-cohort it was 19–44% higher. The extent of lower incisor gingival recessions did not differ significantly between the treated Class II participants and the untreated Class I controls (0.1 ± 0.2 vs. 0.0 ± 0.1 mm).

Conclusion

Patients with orthodontically treated severe Class II malocclusions had a lower risk for oral health impairment than the general population. The risk corresponded to that of untreated Class I controls (without orthodontic Tx need during adolescence).

Zusammenfassung

Ziel

Untersucht werden sollten mögliche langfristige (≥15 Jahre) Effekte einer kieferorthopädischen Klasse-II-Behandlung auf die Mundgesundheit.

Material und Methode

Alle Patienten (Abteilung für Kieferorthopädie, Justus-Liebig-Universität Gießen, Deutschland), bei welchen eine Klasse-II-Behandlung (Herbst-Multibracket-Apparatur, Ende der aktiven Behandlung vor ≥15 Jahren) durchgeführt worden war und die zu einer Nachuntersuchung (Befragung, klinische Untersuchung, Anfertigung von Studienmodellen und Fotos) bereit waren. Zur Beurteilung der Langzeiteffekte auf die Mundgesundheit wurden außerdem die Unterlagen von unmittelbar nach der Behandlung verwendet. Die Daten wurden mit denen korrespondierender bevölkerungsrepräsentativer Alterskohorten sowie unbehandelter Klasse-I-Kontrollen ohne kieferorthopädischen Behandlungsbedarf während der Adoleszenz verglichen.

Ergebnisse

Von 152 Patienten konnten 72 lokalisiert werden, diese nahmen im Alter von 33,7 ± 3,0 Jahren an der Studie teil (Alter vor Behandlung: 14,0 ± 2,7). Die Mehrheit (70,8 %) gab an, mit ihren Zähnen und der Funktion des Kauorgans vollständig zufrieden zu sein. Der DMFT(„decayed, missing, filled teeth“)-Index zeigte einen Wert von 7,1 ± 4,8 und war damit fast identisch mit dem der unbehandelten Kontrollen (7,9 ± 3,6). Im Gegensatz dazu zeigte die korrespondierende bevölkerungsrepräsentativer Alterskohorte (DMS[Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie] V) einen um 56 % höheren Wert. Der durchschnittliche Maximalwert des CPI („community periodontal index“) zeigte bei den Teilnehmern einen Wert von 1,6 ± 0,6. Bei den unbehandelten Kontrollen war der Wert vergleichbar (1,7 ± 0,9), während er in der korrespondierenden bevölkerungsrepräsentativen Alterskohorte (DMS V) um 19–44 % höher war.

Das Ausmaß gingivaler Rezessionen an den unteren Schneidezähnen unterschied sich nicht systematisch zwischen den behandelten Klasse-II-Patienten und den unbehandelten Klasse-I-Kontrollen (0,1 ± 0,2 vs. 0,0 ± 0,1 mm).

Schlussfolgerung

Patienten, die eine kieferorthopädische Behandlung bei ausgeprägter Klasse-II-Malokklusion erfahren hatten, zeigten ein geringeres Risiko für eine Beeinträchtigung der Mundgesundheit als die Allgemeinbevölkerung. Das Risiko entsprach dem von unbehandelten Klasse-I-Kontrollen (ohne kieferorthopädischen Behandlungsbedarf während der Adoleszenz).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Addy M, Dummer PM, Griffiths G, Hicks R, Kingdon A, Shaw WC (1986) Prevalence of plaque, gingivitis and caries in 11–12-year-old children in South Wales. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 14:115–118

Addy M, Griffiths GS, Dummer PMH, Kingdon A, Hicks R, Hunter ML, Newcombe RG, Shaw WC (1988) The association between tooth irregularity and plaque accumulation, gingivitis, and caries in 11–12-year-old children. Eur J Orthod 10:76–83

Ainamo J, Barmes D, Beagrie G, Cutress T, Martin J, Sardo-Infirri J (1982) Development of the World Health Organization (WHO) Community Periodontal Index of Treatment Needs (CPITN). Int Dent J 32:281–291

Ankkuriniemi O, Ainamo J (1997) Dental health and dental treatment needs among recruits of the Finnish Defence Forces, 1919–91. Acta Odontol Scand 55:192–197

Årtun J, Garol JD, Little RM (1996) Long-term stability of mandibular incisors following successful treatment of Class II, Division 1, malocclusions. Angle Orthod 66:229–238

Benson PE, Javidi H, DiBiase AT (2015) What is the value of orthodontic treatment? Br Dent J 218:185–190

Bock NC, von Bremen J, Ruf S (2016) Stability of Class II fixed functional appliance therapy—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 38:129–139

Bock NC, Saffar M, Hudel H, Evälahti M, Heikinheimo K, Rice DPC, Ruf S (2017) Herbst-multibracket appliance therapy of class II:1 malocclusions—long-term stability and outcome quality after ≥ 15 years in comparison to untreated controls. Eur J Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjx051

Bock NC, Saffar M, Hudel H, Evälahti M, Heikinheimo K, Rice DPC, Ruf S (2017) Outcome quality and long-term (≥15 years) stability after class II:2 Herbst-multibracket appliance treatment in comparison to untreated class I controls. Eur J Orthod. https://doi.org/10.1093/ejo/cjx091

Bollen AM (2008) Effects of malocclusions and orthodontics on periodontal health: evidence from a systematic review. J Dent Educ 72:912–918

Bollen AM, Cunha-Cruz J, Bakko DW, Huang GJ, Hujoel PP (2008) The effects of orthodontic therapy on periodontal health. J Am Dent Assoc 139:413–422

Bondemark L, Holm AK, Hansen K, Axelsson S, Mohlin B, Brattstrom V, Paulin G, Pietila T (2007) Long-term stability of orthodontic treatment and patient satisfaction. A systematic review. Angle Orthod 77:181–191

Booth FA, Edelman JM, Proffit WR (2008) Twenty-year follow-up of patients with permanently bonded mandibular canine-to-canine retainers. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 133:70–76

Chen W, Zhou Y (2015) Caries outcomes after orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances: a longitudinal prospective study. Int J Clin Exp Med 15:2815–2822

Crocombe LA, Mejia GC, Koster CR, Slade GD (2009) Comparison of adult oral health in Australia, the USA, Germany and the UK. Aust Dent J 54:147–153

DAJ (2005) Epidemiologische Begleituntersuchungen zur Gruppenprophylaxe 2004. Gutachten aus den Bundesländern bzw. Landesteilen Schleswig-Holstein, Bremen, Hamburg, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein, Westfalen, Hessen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Baden-Württemberg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Berlin, Brandenburg, Sachsen-Anhalt, Thüringen, Saarland, Bayern, Sachsen. Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Jugendzahnpflege, Bonn

DAJ (2010) Epidemiologische Begleituntersuchungen zur Gruppenprophylaxe 2004. Gutachten aus den Bundesländern bzw. Landesteilen Schleswig-Holstein, Bremen, Hamburg, Niedersachsen, Nordrhein, Westfalen, Hessen, Rheinland-Pfalz, Baden-Württemberg, Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, Berlin, Brandenburg, Sachsen-Anhalt, Thüringen, Saarland, Bayern, Sachsen. Deutsche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Jugendzahnpflege, Bonn

D’Antò V, Bucci R, Franchi L, Rongo R, Michelotti A, Martina R (2015) Class II functional orthopaedic treatment: a systematic review of systematic reviews. J Oral Rehabil 42:624–642

Davies TM, Shaw WC, Worthington HV, Addy M, Dummer P, Kingdon A (1991) The effect of orthodontic treatment on plaque and gingivitis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 99:155–161

Ehsani S, Nebbe B, Normando D, Lagravere MO, Flores-Mir C (2015) Short-term treatment effects produced by the Twin-block appliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 37:170–176

Feliu JL (1982) Long-term benefits of orthodontic treatment on oral hygiene. Am J Orthod 82:473–477

Glans R, Larsson E, Øgaard B (2003) Longitudinal changes in gingival condition in crowded and noncrowded dentitions subjected to fixed orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 124:679–682

Hafez HS, Shaarawy SM, Al-Sakiti AA, Mostafa YA (2012) Dental crowding as a caries risk factor: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 142:443–450

Heikinheimo K, Nyström M, Heikinheimo T, Pirttiniemi P, Pirinen S (2012) Dental arch width, overbite and overjet in a Finnish population with normal occlusion between the ages of 7 and 32 years. Eur J Orthod 34:418–426

Helm S, Petersen PE (1989) Causal relation between malocclusion and caries. Acta Odontol Scand 47:217–221

Henrikson J, Persson M, Thilander B (2001) Long-term stability of dental arch form in normal occlusion from 13 to 31 years of age. Eur J Orthod 23:51–61

Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (1991) Mundgesundheitszustand und -verhalten in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV, Köln

Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (1999) Dritte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS III). Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV, Köln

Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (2006) Vierte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS IV). Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV, Köln

Institut der Deutschen Zahnärzte (2016) Fünfte Deutsche Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS V). Deutscher Zahnärzte Verlag DÄV, Köln

Janson G, Sathler R, Fernandes TM, Branco NC, Freitas MR (2013) Correction of class II malocclusion with class II elastics: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 143:383–392

Kämppi A, Tanner T, Päkkilä J, Patinen P, Järvelin MR, Tjäderhane L, Anttonen V (2013) Geographical distribution of dental caries prevalence and associated factors in young adults in Finland. Caries Res 47:346–354

Kerosuo H, Kerosuo E, Niemi M, Simola H (2000) The need for treatment and satisfaction with dental appearance among young Finnish adults with and without a history of orthodontic treatment. J Orofac Orthop 61:330–340

Klein H, Palmer CE, Knutson JW (1938) Studies on dental caries: I. Dental status and dental needs of elementary schoolchildren. Public Health Rep 53:751–765

Koretsi V, Zymperdikas VF, Papageorgiou SN, Papadopoulos MA (2015) Treatment effects of removable functional appliances in patients with class II malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 37:418–434

Landry RG, Jean M (2002) Periodontal Screening and Recording (PSR) Index: precursors, utility and limitations in a clinical setting. Int Dent J 52:35–40

Löe H, Ånerud Å, Boysen H (1992) The natural history of periodontal disease in man: prevalence, severity, and extent of gingival recession. J Periodontol 63:489–495

Maia NG, Normando D, Maia FA, Ferreira MA, do Socorro Costa Feitosa Alves M (2010) Factors associated with long-term patient satisfaction. Angle Orthod 80:1155–1158

Mazor KM, Clauser BE, Field T, Yood RA, Gurwitz JH (2002) A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res 37:1403–1417

Meyle J, Jepsen S (2000) Der parodontale Screening-Index (PSI). dgp-news, Sonderausgabe, pp 8–10

Millett DT, Cunningham SJ, O’Brien KD, Benson PE, de Oliveira CM (2012) Treatment and stability of class II division 2 malocclusion in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 142:159–169

National Institute for Health and Welfare (2010) A nordic project of quality indicators for oral health care. Report 32/2010. National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki

National Public Health Institute (2008) Oral health in the Finnish adult population. Publications of the National Public Health Institute B25/2008. National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki

Pacha MM, Fleming PS, Johal A (2016) A comparison of the efficacy of fixed versus removable functional appliances in children with class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Eur J Orthod 38:621–630

Pancherz H, Bjerklin K (2015) Mandibular incisor inclination, tooth irregularity, and gingival recessions after Herbst therapy: a 32-year follow-up study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 146:310–318

Pancherz H, Bjerklin K, Lindskog-Stokland B, Hansen K (2014) Thirty-two-year follow-up study of Herbst therapy: a biometric dental cast analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 145:15–27

Pancherz H, Salé H, Bjerklin K (2015) Signs and symptoms of TMJ disorders in adults after adolescent Herbst therapy: a 6-year and 32-year radiographic and clinical follow-up study. Angle Orthod 85:735–742

Peltola JS, Ventä I, Haahtela S, Lakoma A, Ylipaavalniemi P, Turtola L (2006) Dental and oral radiographic findings in first-year university students in 1982 and 2002 in Helsinki, Finland. Acta Odontol Scand 64:42–46

Polson AM, Subtelny JD, Meitner SW, Polson AP, Sommers EW, Iker HP, Reed BE (1988) Long-term periodontal status after orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 93:51–58

Ravaghi V, Kavand G, Farrahi N (2015) Malocclusion, past orthodontic treatment, and satisfaction with dental appearance among Canadian adults. J Can Dent Assoc 81:f13

Richmond S, Shaw WC, Roberts CT, Andrews M (1992) The PAR Index (Peer Assessment Rating): methods to determine outcome of orthodontic treatment in terms of improvement and standards. Eur J Orthod 14:180–187

Rody WJ Jr, Elmaraghy S, McNeight AM, Chamberlain CA, Antal D, Dolce C, Wheeler TT, McGorray SP, Shaddox LM (2016) Effects of different orthodontic retention protocols on the periodontal health of mandibular incisors. Orthod Craniofac Res 19:198–208

Rühl J, Bock N, Ruf S (2017) Prevalence and magnitude of recessions during and after Herbst-Multibracket treatment—an analysis of 492 consecutive Class II, division 1 cases. Eur J Orthod 39:e23

Ruf S, Hansen K, Pancherz H (1998) Does orthodontic proclination of lower incisors in children and adolescents cause gingival recession? Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 114:100–106

Sadowsky C, BeGole EA (1981) Long-term effects of orthodontic treatment on periodontal health. Am J Orthod 80:156–172

Schwartz JP, Raveli TB, Schwartz-Filho HO, Raveli DB (2016) Changes in alveolar bone support induced by the Herbst appliance: a tomographic evaluation. Dental Press J Orthod 21:95–101

Splieth C, Schwahn C, Bernhardt O, Kocher T, Born G, John U, Hensel E (2003) Caries prevalence in an adult population: results of the Study of Health in Pomerania, Germany (SHIP). Oral Health Prev Dent 1:149–155

Stenvik A, Espeland L, Berg RE (2011) A 57-year follow-up of occlusal changes, oral health, and attitudes toward teeth. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 139:S102–S108

Thomson WM (2002) Orthodontic treatment outcomes in the long-term: findings from a longitudinal study of New Zealanders. Angle Orthod 72:449–455

Tukey JW (1977) Exploratory data analysis. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company, Reading

Tuominen ML, Nyström M, Tuominen RJ (1995) Subjective and objective orthodontic treatment need among orthodontically treated and untreated Finnish adolescents. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 23:286–290

Yang X, Zhu Y, Long H, Zhou Y, Jian F, Ye N, Gao M, Lai W (2016) The effectiveness of the Herbst appliance for patients with class II malocclusion: a meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 38:324–333

Westerlund A, Oikimoui C, Ransjö M, Ekestubbe A, Bresin A, Lund H (2017) Cone-beam computed tomographic evaluation of the long-term effects of orthodontic retainers on marginal bone levels. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 151:74–81

Zymperdikas VF, Koretsi V, Papageorgiou SN, Papadopoulos MA (2016) Treatment effects of fixed functional appliances in patients with class II malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod 38:113–126

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

N. Bock, M. Saffar, H. Hudel, M. Evälahti, K. Heikinheimo, D. Rice and S. Ruf declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

Supplementary Table 1

Structure of the relevant data of the Fourth and Fifth German Oral Health Studies (DMS IV and DMS V), which were population-representative cross-sectional studies with randomly chosen participants of different age cohorts selected on the basis of the relevant WHO criteria and the customary principles of international oral epidemiology.

Ergänzende Tabelle 1 Struktur der relevanten Daten der vierten und fünften deutschen Mundgesundheitsstudie (DMS IV und DMS V), die als bevölkerungsrepräsentative Querschnittsstudien durchgeführt wurden mit zufällig ausgewählten Teilnehmern verschiedener Alterskohorten, selektiert auf Basis der relevanten WHO-Kriterien und üblicher Prinzipien internationaler oraler Epidemiologie.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bock, N., Saffar, M., Hudel, H. et al. Long-term effects of Class II orthodontic treatment on oral health. J Orofac Orthop 79, 96–108 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-018-0125-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00056-018-0125-5