Abstract

The correct analysis of heat transport at nanoscale is one of the main reasons of new developments in physics and nonequilibrium thermodynamic theories beyond the classical Fourier law. In this paper, we provide a two-temperature model which allows to describe the different regimes which electrons and phonons can undergo in the heat transfer phenomenon. The physical admissibility of that model is showed in view of second law of thermodynamics. The above model is applied to study the propagation of heat waves in order to point out the special role played by nonlocal and nonlinear effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

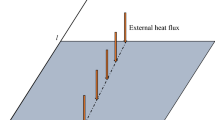

Modern ultrafast laser-assisted manufacturing technology is empowering the fabrication of miniaturized nano/microscale devices for electronics, optics, medicine and energy applications [1, 2]. A continuous control of the temperature’s rise should be required to avoid any possible problem in the laser-assisted nanoscale manufacturing. The analysis of heat transport in those situations (which may be also labeled as extreme, since they are “very far from equilibrium”), indeed, requires the use of theoretical models which go beyond the classical Fourier law; the heat transport, in fact, might be no longer diffusive (and therefore describable by the classical Fourier law), but ballistic, or hydrodynamic [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10], since miniaturized nano/microscale devices usually show characteristic dimensions which are comparable to (or smaller than) the mean free path of the heat carriers.

This paper deals, therefore, with the heat transport phenomenon at nanoscale which is a very hard, but compelling and fashionable research playground. In modeling that phenomenon, indeed, one should also observe that:

-

i.

although with a different importance, in common materials used at nanoscale both the electrons and the lattice vibrations (i.e., the phonons) are the heat carriers [11,12,13,14]. Both heat carriers are not in an equilibrium state during the heat transfer;

-

ii.

thermodynamic constitutive equations containing nonlocal and nonlinear spatial terms are needed when the attention is put on systems subjected to important spatial gradients [4, 15,16,17,18].

According with the above observations, by regarding the electrons and the phonons as a mixture of heat carriers flowing through the crystal lattice, and assuming that they are endowed with their own temperatures [19, 20], here we propose a theoretical model based on the following equations which allow to take into account memory, nonlocal and nonlinear effects:

In Eqs. (1):

-

\(\theta ^e\) and \(\theta ^p\) are, respectively, the electron temperature and the phonon temperature. They are related to the internal energy of electrons \(u^e\) and that of phonons \(u^p\), respectively, by the constitutive assumptions

$$\begin{aligned}&u^e=c_{\mathrm{v}}^e\theta ^e \end{aligned}$$(2a)$$\begin{aligned}&u^p=c_{\mathrm{v}}^p\theta ^p \end{aligned}$$(2b)with \(c_{\mathrm{v}}^e\) and \(c_{\mathrm{v}}^p\) being, respectively, the specific heat of electrons and of phonons [19, 20]. The two above contributions to the internal energy (per unit volume) u of the whole system are such that

$$\begin{aligned} u=u^e+u^p \end{aligned}$$(3)whereas the total specific heat is \(c_{\mathrm{v}}=c_{\mathrm{v}}^e+c_\mathrm{v}^p\).

-

\(q_i^e\) and \(q_i^p\) are, respectively, the electron contribution and the phonon contribution to the local heat flux \(q_i\) [19, 20]. These two different contributions are such that

$$\begin{aligned} q_i=q_i^e+q_i^p \end{aligned}$$(4) -

\(Q_{ij}^e\) and \(Q_{ij}^p\) are second-order tensors representing, respectively, the electron contribution and the phonon contribution to the flux of \(q_i\) [4, 21,22,23]. These two different contributions are such that the flux of heat flux \(Q_{ij}\) of the whole system is

$$\begin{aligned} Q_{ij}=Q_{ij}^e+Q_{ij}^p \end{aligned}$$(5) -

\(\tau _{1e}\) and \(\tau _{1p}\) are, respectively, the relaxation time of \(q_i^e\) and of \(q_i^p\).

-

\(\tau _{2e}\) and \(\tau _{2p}\) are, respectively, the relaxation time of \(Q_{ij}^e\) and of \(Q_{ij}^p\).

-

\(\lambda _e\) and \(\lambda _p\) are, respectively, the thermal conductivity of electrons and of phonons.

-

\(\ell _e\) and \(\ell _p\) are, respectively, the mean free path of electrons and of phonons.

The framework of the present paper is the following. In Sect. 2, we prove the thermodynamic compatibility of the theoretical model introduced by Eqs. (1). In Sect. 3, we use that model to study the propagation of heat waves in a rigid body, pointing out the role played by nonlocal and nonlinear effects. In Sect. 4, we provide final comments and point out the application limits of the proposed model.

2 Thermodynamic considerations

Equations (1) represent the basic tool in this paper: in Sect. 3, in particular, they will be used to analyze the propagation of heat waves at nanoscale. Although some comments on physical grounds about Eqs. (1) will be given in Sect. 4, we here underline that they do not follow from a rigorous microscopic derivation. As a consequence, it is necessary to primarily check their physical admissibility (in order to avoid any possible violation of the basic principles of continuum physics). In this section, therefore, we prove the thermodynamic compatibility of the theoretical model expressed by Eqs. (1). To this aim, we put ourselves in the context of extended thermodynamics [4, 15, 21, 24, 25] and assume the following state space:

Then we start from the local balance of the specific entropy s, that is,

wherein \(J_i^s\) is the specific entropy flux and \(\sigma ^s\) is the specific entropy production.

According with the classical Liu procedure for the exploitation of the second law of thermodynamics [26], a linear combination of the specific entropy production and of Eqs. (1) (which represent the constraints introduced by the state–space variables) has to be always non-negative along any admissible thermodynamic process. As a consequence, from the coupling of Eqs. (1) and the left-hand side of Eq. (6), we have that the following extended entropy inequality

has to be always fulfilled, whatever the thermodynamic process is. In the extended entropy inequality above the functions \(\Lambda ^e\), \(\Lambda ^e_i\), \(\Lambda ^e_{ij}\), \(\Lambda ^p\), \(\Lambda ^p_i\) and \(\Lambda ^p_{ij}\) are the so-called Lagrange multipliers; they may depend on the whole set of state–space variables, in principle.

The agreement of Eqs. (1) with second law of thermodynamics cannot be checked until constitutive assumptions on s and \(J_i^s\) have been given, since the latter functions do not belong to the state space. In order to remain on a very general level and let the second law give information about them, here we assume

The insertion of Eqs. (8) into inequality (7) leads (by straightforward calculations) to the following sets of necessary and sufficient conditions which guarantee that second law of thermodynamics is always fulfilled

and

together with the following reduced entropy inequality:

According with the thermodynamic restrictions in Eqs. (8)–(10), by direct calculations it is indeed possible to verify that the two-temperature model based on Eqs. (1) always agrees with second law if, for example, the following generalized forms of the specific entropy and specific entropy flux are used, respectively,

wherein \(s_0\left( \theta ^e;\theta ^p\right) \) is the local equilibrium entropy, and

are suitable vector-valued functions, with \(\alpha ^e=\alpha ^e\left( \theta ^e\right) \) and \(\alpha ^p=\alpha ^p\left( \theta ^p\right) \) being suitable scalar-valued functions of the indicated arguments, and \(\left| q_i^e\right| \) and \(\left| q_i^p\right| \) being the moduli of the indicated vectors.

The above considerations allow us to claim that the two-temperature model introduced by Eqs. (1) has well-posed theoretical basis.

3 Heat wave propagation

Advanced materials could experience very low temperatures, or extremely high-temperature gradients, for which a precise heat transport model should be considered to capture temperature’s rise from thermal wave propagation. Therefore, starting from Eqs. (1), in this section we study the propagation of heat (H-) waves. From the practical point of view, H-waves can be generated by periodically varying in time the temperature in a point of the medium at hand with respect to its steady-state reference level. A solitary H-wave, instead, comes into being and travels along the medium when the latter is heated with a heat pulse.

For our convenience, here we use the tool of the acceleration (A-) waves, namely traveling surfaces \({\mathcal {S}}\), across which all the state–space variables are continuous, but their space and/or time derivatives suffer at most finite discontinuities. For some mathematical details about the use of A-waves, we refer the readers to Ref. [27] (see therein the Appendix section). A very outstanding reference about the A-waves is also the book by Straughan [28].

We also suppose that the region ahead \({\mathcal {S}}\) is such that

\(\forall t\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\), with \(\theta _0\) and \(q_i^0\) being stationary constant reference levels.

3.1 Heat wave speeds

By taking the jump of each of Eqs. (1), we firstly have

and then

once the use of the classical Hadamard relations [27,28,29] has been made. In Eqs. (16), the functions \(\Theta ^e\left( t\right) =[\![\theta _{,_{i}}n_i]\!]\), \(\Phi _i^e\left( t\right) =[\![q^e_{i,_{j}}n_j]\!]\), \(\Psi _{ij}^e\left( t\right) =[\![Q^e_{{ij,}_k}n_k]\!]\), \(\Theta ^p\left( t\right) =[\![\theta _{,_{i}}n_i]\!]\), \(\Phi _i^p\left( t\right) =[\![q^p_{i,_{j}}n_j]\!]\) and \(\Psi _{ij}^p\left( t\right) =[\![Q^p_{{ij,}_k}n_k]\!]\) are the A-wave amplitudes. Moreover, therein \(\text {V}\) means the A-wave speed (or, equivalently, the H-wave speed), and \(n_i\) means the normal unit to the A-wave front.

By straightforward calculations, it is possible to obtain that Eqs. (16) do not only admit the trivial solution if, and only if, the following relation holds:

Equation (17) allows us to claim the following result: the two-temperature theoretical model, introduced by Eqs. (1), predicts that a periodical variation of the local temperature in a point of the system generates two different A-waves which propagate with different speeds. Those speeds are given by

wherein we have introduced the following speeds

and the following nondimensional scalar-valued functions

Throughout the present paper, we use the appellation electronic heat (EH-) wave for the A-wave whose speed is given by Eq. (18a) and the appellation phononic heat (PH-) wave for the A-wave whose speed is given by Eq. (18b).

As it is clearly showed by Eqs. (18), the EH-wave speed diverges either when \(\tau _{1e}\rightarrow 0\) or when \(\tau _{2e}\rightarrow 0\). Similarly, the PH-wave speed diverges either when \(\tau _{1p}\rightarrow 0\) or when \(\tau _{2p}\rightarrow 0\).

Below we comment about the role played by nonlocal and nonlinear effects.

3.1.1 Nonlocal effects and heat-wave speeds

Nonlocal effects influence both the EH-wave speed, and the PH-wave speed. According to Eqs. (18), those effects, in fact, are introduced by \(\psi _e\) in \(\text {V}^e\) and by \(\psi _p\) in \(\text {V}^p\). Since those functions are always positive, it is possible to claim that nonlocal effects enhance the speeds of propagation. In fact, when nonlocal effects are negligible, i.e., if we may set \(\psi _e=0\) and \(\psi _p=0\) in Eqs. (18), those speeds become

3.1.2 Nonlinear effects and heat-wave speeds

Throughout the present paper, we use the appellation positive (\(_+\)) for the H-wave which is propagating in the same direction of the average heat flux \(q_j^0\) and the appellation negative (\(_-\)) for the H-wave which is propagating in the opposite direction of the average heat flux \(q_j^0\).

Nonlinear effects influence both the EH-wave speed, and the PH-wave speed. According to Eqs. (18), those effects, in fact, are introduced by \(\phi _e\) in \(\text {V}^e\) and by \(\phi _p\) in \(\text {V}^p\). Since the sign of the scalar product \(q_j^0n_j\) depends on the direction of propagation, from Eqs. (20) it follows that

-

\(\phi _e>0\) and \(\phi _p>0\) for positive A-waves

-

\(\phi _e<0\) and \(\phi _p<0\) for negative A-waves

As a consequence, from Eqs. (18) it follows that both \(\text {V}^e\) and \(\text {V}^p\) depend on the direction of propagation of the H-waves. In particular, from the above results we have \(\text {V}^e_+\le \text {V}^e_-\) and \(\text {V}^p_+\le \text {V}^p_-\).

When nonlinear effects are negligible, i.e., when \(\phi _e=0\) and \(\phi _p=0\), Eqs. (18) become

and both those speeds no longer depend on the direction of propagation.

3.2 Heat wave amplitudes

When the A-wave amplitude becomes infinite, we may claim that the A-wave becomes a shock wave.

Differentiating with respect to time each of Eqs. (1) and then evaluating their jumps through \({\mathcal {S}}\), we have

which leads to

when the Hadamard relations [27,28,29] are employed in a recursive way. Observing that from Eqs. (16a), (16c), (16d) and (16f), one, respectively, has

by coupling Eqs. (24a)–(24c) and Eqs. (24d)–(24f), respectively, the following Bernoully-type ODEs arise:

For the sake of computational convenience, in writing ODEs (26) we introduced the following nondimensional variable

as well as the following nondimensional functions

once Eqs. (18)–(20) have been taken into account. If \(\gamma _e\ne 4\phi _e\) and \(\gamma _p\ne 4\phi _p\), then ODEs (26) can be solved to find

wherein \({\overline{\Theta }}_0={\overline{\Theta }}_e\left( t^{\star }\equiv 0\right) ={\overline{\Theta }}_p\left( t^{\star }\equiv 0\right) \) are the initial conditions, and

When \(\gamma _e=4\phi _e\), one simply has \({\overline{\Theta }}_e\left( t^{\star }\right) =0\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\), and when \(\gamma _p=4\phi _p\), one simply has \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\left( t^{\star }\right) =0\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\).

Although in the very general case the initial condition on the temperature-wave amplitude \({\overline{\Theta }}_0\) may be either positive or negative, here we assume \({\overline{\Theta }}_0\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\). Holding this assumption, below we comment more in detail some results arising from Eqs. (29).

3.2.1 Positive heat waves

According with the observations made in Sect. 3.1.2, we start to observe that from Eqs. (28) one may have that

-

\(\gamma _e>4\phi _e\Rightarrow \alpha _e>0\), and \(\gamma _p>4\phi _p\Rightarrow \alpha _p>0\)

-

\(\gamma _e<4\phi _e\Rightarrow \alpha _e<0\), and \(\gamma _p<4\phi _p\Rightarrow \alpha _p<0\)

whereas from Eqs. (30) it follows that \(\epsilon _e>0\) and \(\epsilon _p>0\), when positive H-waves are propagating through the medium. In this situation, the main cases below may occur.

-

1.

If \(\gamma _e>4\phi _e\) and \(\gamma _p>4\phi _p\), then both \({\overline{\Theta }}_e\), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will decay to zero. We may claim, therefore, that in this case both the EH-waves, and the PH-waves will be damped.

-

2.

If \(\gamma _e<4\phi _e\) and \(\gamma _p<4\phi _p\), then both \({\overline{\Theta }}_e\), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will blow up, respectively, at the following finite values

$$\begin{aligned}&t^{\star }_e=-\alpha _e^{-1}\ln \left( 1+\frac{1}{{\overline{\Theta }}_0\epsilon _e}\right) \end{aligned}$$(31a)$$\begin{aligned}&t^{\star }_p=-\alpha _p^{-1}\ln \left( 1+\frac{1}{{\overline{\Theta }}_0\epsilon _p}\right) \end{aligned}$$(31b)We may claim, therefore, that in this case both the EH-waves, and the PH-waves will become shock waves.

3.2.2 Negative heat waves

According with the observations made in Sect. 3.1.2, we start to observe that in the case of negative H-waves from Eqs. (28) one has \(\alpha _e>0\) and \(\alpha _p>0\), whereas from Eqs. (30) one has \(\epsilon _e<0\) and \(\epsilon _p<0\). By indicating with \(\epsilon _m=\text {min}\left( \left| \epsilon _e\right| ;\left| \epsilon _p\right| \right) \), and with \(\epsilon _M=\text {max}\left( \left| \epsilon _e\right| ;\left| \epsilon _p\right| \right) \), in this situation the cases below may occur.

-

1.

If \({\overline{\Theta }}_0\in \left( 0;\epsilon _M^{-1}\right) \), then both \({\overline{\Theta }}_e\), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will decay to zero. We may claim, therefore, that in this case both the EH-waves, and the PH-waves will be damped.

-

2.

If \({\overline{\Theta }}_0=\epsilon _M^{-1}\), then

-

a.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will decay to zero, and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will always remain constant (i.e., \({\overline{\Theta }}_p=-\epsilon _p\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\)), when \(\epsilon _p<\epsilon _e\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will be damped, and the PH-waves will not change their shapes.

-

b.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will always remain constant (i.e., \({\overline{\Theta }}_e=-\epsilon _e\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\)), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will decay to zero, when \(\epsilon _e<\epsilon _p\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will not change their shapes, and the PH-waves will be damped.

-

a.

-

3.

If \({\overline{\Theta }}_0\in \left( \epsilon _M^{-1};\epsilon _m^{-1}\right) \), then

-

a.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will decay to zero, and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_p\) given by Eq. (31b), when \(\epsilon _p<\epsilon _e\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will be damped, and the PH-waves will become shock waves.

-

b.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_e\) given by Eq. (31a), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will decay to zero, when \(\epsilon _e<\epsilon _p\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will become shock waves, and the PH-waves will be damped.

-

a.

-

4.

If \({\overline{\Theta }}_0=\epsilon _m^{-1}\), then

-

a.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will always remain constant (i.e., \({\overline{\Theta }}_e=-\epsilon _e\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\)), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_p\) given by Eq. (31b), when \(\epsilon _p<\epsilon _e\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will not change their shapes, and the PH-waves will become shock waves.

-

b.

\({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_e\) given by Eq. (31a), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will always remain constant (i.e., \({\overline{\Theta }}_p=-\epsilon _p\), \(\forall t^{\star }\in {\mathbb {R}}^+\)), when \(\epsilon _e<\epsilon _p\). We may claim, therefore, that in this case the EH-waves will become shock waves, and the PH-waves will not change their shapes.

-

a.

-

5.

If \({\overline{\Theta }}_0>\epsilon _m^{-1}\), then \({\overline{\Theta }}_e\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_e\) given by Eq. (31a), and \({\overline{\Theta }}_p\) will blow up at the finite value \(t^{\star }_p\) given by Eq. (31b). We may claim, therefore, that in this case both the EH-waves and the PH-waves will become shock waves.

4 Conclusions

From the theoretical point of view, the analysis of heat transport at nanoscale is not an easy task, owing to several very complex mechanisms involved in that phenomenon which, however, has been one of the driving forces in the shaping of modern physics and modern nonequilibrium thermodynamic theories [3, 4, 8, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22].

A general model of heat transport at nanoscale should not only include a detailed account of nonlocal and nonlinear effects (since at nanoscale the characteristic size may be comparable to the mean free path of heat carriers and consequently some the thermal properties might change), but it should also take into account the possibility that the electron temperature (due to electron–electron collisions) may be different from the phonon temperature (due to phonon–phonon collisions) [30].

In this paper, we therefore proposed the two-temperature model in Eqs. (1) in order to describe heat transport at nanoscale when the contributions of the different heat carriers (namely, the electrons and the phonons) are taken into account; in fact, according to Eqs. (3)–(5) in that theoretical model we have decomposed in the electron and phonon contributions, respectively, the specific internal energy of the whole system u, the local heat flux \(q_i\) and the flux of heat flux \(Q_{ij}\). Along with the approach of the kinetic theory [3], in that theoretical model the heat carriers have been regarded as a gas-like collection, flowing through the crystal lattice [3, 19, 20], similar to a mixture of gases wherein all the constituents have their own temperature and obey the same balance laws as a single fluid [31, 32].

Equations (1) allow to introduce both nonlocal effects (by means of the terms \(\ell _eq_{i,_{j}}^e\) and \(\ell _pq_{i,_{j}}^p\)) and nonlinear effects (by means of the terms \(\dfrac{2q_j^eq_{i,_{j}}^e}{c_{\mathrm{v}}^e\theta ^e}\) and \(\dfrac{2q_j^pq_{i,_{j}}^p}{c_{\mathrm{v}}^p\theta ^p}\)). The role played by those effects has been pointed out in the propagation of heat waves; the analysis carried out in Sect. 3 displays, in particular, that those effects influence both the speed of the heat waves (which can be different, depending on the direction of propagation), and the wave amplitudes in such a way that a thermal wave may also become thermal shock wave. It seems worth noticing that Eqs. (1) also encompass the possibility that in some situations nonlocal and/or nonlinear effects may influence only one of the heat carrier collections. For example, if they have a vanishingly small influence on the electrons, then Eqs. (1) become

whereas one would have

if nonlocal and nonlinear effects do not play any relevant role on phonos. Intermediate situations can be, however, also possible.

Concerning the thermodynamic aspects, we have pointed out that Eqs. (1) yield that both the specific entropy s, and the specific entropy flux \(J_i^s\) contain nonclassical contributions related to the fluxes and their corresponding higher-order fluxes.

At the very end, we draw again the attention of the readers on the possible implications in practical applications of theoretical models beyond the classical Fourier law: they could allow a continuous control of the temperature and avoid any possible rise of it. Owing to this, further comments about Eqs. (1), as well as about the limit of application of the two-temperature model introduced in the present paper, are needed.

4.1 Comments on the origin of Eqs. (1)

As we previously observed, Eqs. (1) do not follow from a rigorous microscopic derivation, although their physical admissibility has been proved by exploiting the second law in Sect. 2. Indeed, without going very deep in the physical details, but still remaining on a general level, we note that on microscopic ground both electrons, and phonons may be viewed as a free particle gas in a box [3]. Both of them can be described through the Boltzmann transport equation. In that equation, the equilibrium distribution function \(f_0\) is given by the Bose–Einstein distribution function (BEdf) in the case of phonons, whereas in the case of electrons \(f_0\) is expressed by the Fermi–Dirac distribution function (FDdf), i.e.,

where \(\hbar =h/\left( 2\pi \right) \) with h as the Planck constant, \(\omega \) is the angular frequency, \(k_B\) is the Boltzmann constant, \(\varepsilon _i\) is the energy of the single-particle state and \(\mu \) is the chemical potential. As it can be easily seen, the BEdf changes the plus one in the denominator of the FDdf into minus one. It is possible to find several situations, as, for example, whenever \(\varepsilon _i-\mu \gg k_{B}T\), in which one can ignore the \(\pm 1\) in the denominator, in order that both distributions reduce to the Boltzmann distribution function [3]. In these cases, on intuitively ground, the solution of the Boltzmann equation both for phonons, and for electrons would lead to equations which display the same mathematical behavior. Therefore, the mathematical structure of Eqs. (1a)–(1c) (holding for the electrons) is similar to that of Eqs. (1d)–(1f) (holding for the phonons).

4.2 Comments on the flux of heat flux

In the theoretical model introduced by Eqs. (1) an important role is played by the flux of the heat flux \(Q_{ij}\), which is indeed decoupled therein in its electron contribution \(Q_{ij}^e\) and in its phonon contribution \(Q_{ij}^p\), according to Eq. (5). Theoretical considerations about \(Q_{ij}^e\) and \(Q_{ij}^p\) can be found in Ref. [23] (see therein Sect. 5), for example. The physical concept of \(Q_{ij}\), indeed, might be not very clear at a first view, but it is simple to understand from a microscopic perspective. The heat flux \(q_i\) is the convective energy flux, proportional to the integral of \(\hbar \omega k_{i}\) over the \(\kappa \)-distribution function, with \(k_{i}\) as the wave vector, indicating the direction of the speed. In an analogous way, the flux of heat flux \(Q_{ij}\) is related to the integral of the tensor \(\hbar \omega k_{i}k_{j}\). In the kinetic theory of gases, the corresponding microscopic operators for \(q_i\) and \(Q_{ij}\) would be, respectively, \(\dfrac{mc^2c_i}{2}\) and \(\dfrac{mc^2c_ic_j}{2}\), m being the mass of the particle and \(c_i\) the peculiar velocity of the particle with respect to the barycentric speed of the gas [4].

4.3 Comments on the relaxation times

From the theoretical point of view, in the proposed two-temperature model the crucial role also played by the four relaxation times \(\tau _{1e}\), \(\tau _{2e}\), \(\tau _{1p}\) and \(\tau _{2p}\) is very clear: they guarantee, in fact, the hyperbolic behavior of Sys. (1).

In practical applications, the modeling of the relaxation times still represents an open and very compelling problem [4, 29, 33, 34]. In principle, they should depend on the whole set of state–space variables [27], as well as the other material functions (i.e., the thermal conductivities and the mean free paths); in Ref. [4] (see, therein, Chap. 6), for example, generic nonlinear expressions for the thermal conductivity and for the relaxation time as functions of the temperature and of the heat flux have been derived from the maximum entropy formalism for harmonic chains, electromagnetic radiation, as well as in the case of classical and relativistic ideal gases. If those material-function dependences were taken into account, a very general nonlinear analysis would have been achieved. In this paper, however, we assumed constant values for all material functions in order to only emphasize the effects of the genuinely nonlinear terms \(\dfrac{2q_j^eq_{i,_{j}}^e}{c_{\mathrm{v}}^e\theta ^e}\) and \(\dfrac{2q_j^pq_{i,_{j}}^p}{c_{\mathrm{v}}^p\theta ^p}\) (contained in Eqs. (1b) and (1e), respectively) since nonlinear terms accounting for products of the temperature gradient (or the heat flux) should be also taken into consideration, owing to the possibility that in nanosystems small temperature differences could lead to high values of temperature gradient. These “genuinely” nonlinear terms may be important in all situations wherein the different thermophysical quantities only display vanishingly small changes with the temperature, i.e., when the material functions can be practically assumed constant.

4.4 Comments on the electron–phonon coupling

A more important limit in possible applications of Eqs. (1) is strictly related to the electron–phonon coupling. We note, in fact, that in the proposed two-temperature model the two different species of heat carriers (i.e., the electrons and the phonons) have been completely decoupled; indeed, the interactions between electrons and quantized lattice vibrations in a solid represent one of the most fundamental realms of study in condensed matter physics. It is well known that the electron–phonon interactions in graphene, for example, play an important role in understanding anomalies of photoemission spectra observed in graphite and graphene, the nonlinear high-energy electron transport in carbon nanotubes, as well as phonon structures in graphite and carbon nanotubes [35, 36]; therefore, the absence of an electron–phonon coupling in Eqs. (1) clearly sets a limit in the application of the two-temperature model proposed in this paper.

Although the electron–phonon interactions can be introduced in several ways in the model equations [13, 19, 34, 37], it has to be noted that their accounting might not lead to an easy task from the practical point of view. In Eqs. (1) (which have to be meant, therefore, only as a first attempt towards a more refined theoretical model), we neglect the electron–phonon interactions in order to reduce to a simpler level the analysis of nonlocal and nonlinear effects, the role of which in the propagation of heat waves is clearly pointed out in this approximation.

References

Wang, G.-X., Prasad, V.: Microscale heat and mass transfer and non-equilibrium phase change in rapid solidification. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 292, 142–148 (2000)

Chowdhury, I.H., Xu, X.: Heat transfer in femtosecond laser processing of metal. Numer. Heat Transf. Part A 44, 219–232 (2003)

Chen, G.: Nanoscale Energy Transport and Conversion–A Parallel Treatment of Electrons, Molecules, Phonons, and Photons. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2005)

Jou, D., Casas-Vázquez, J., Lebon, G.: Extended Irreversible Thermodynamics, 4th edn. Springer, Berlin (2010)

Fryer, M.J., Struchtrup, H.: Moment model and boundary conditions for energy transport in the phonon gas. Cont. Mech. Thermodyn. 26, 593–618 (2014)

Lee, S., Broido, D., Esfarjani, K., Chen, G.: Hydrodynamic phonon transport in suspended graphene. Nat. Commun. 6, 6290 (2015)

Sellitto, A., Carlomagno, I., Jou, D.: Two-dimensional phonon hydrodynamics in narrow strips. Proc. R. Soc. A 471, 20150376 (2015)

Dong, Y.: Dynamical Analysis of Non-Fourier Heat Conduction and Its Application in Nanosystems. Springer, New York (2016)

Tang, D.-S., Hua, Y.-C., Nie, B.-D., Cao, B.-Y.: Phonon wave propagation in ballistic-diffusive regime. J. Appl. Phys. 119, 124301 (2016)

Vázquez, F., Ván, P., Kovács, R.: Ballistic-diffusive model for heat transport in superlattices and the minimum effective heat conductivity. Entropy 22, 167 (2020)

Roukes, M.L., Freeman, M.R., Germain, R.S., Richardson, R.C., Ketchen, M.B.: Hot electrons and energy transport in metals at millikelvin temperatures. Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 422–425 (1985)

Sergeev, A.V.: Electronic Kapitza conductance due to inelastic electron-boundary scattering. Phys. Rev. B 58, R10199–R10202 (1998)

Majumdar, A., Reddy, P.: Role of electron-phonon coupling in thermal conductance of metal-nonmetal interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 84, 4768–4770 (2004)

Sobolev, S.L.: Nonlocal two-temperature model: application to heat transport in metals irradiated by ultrashort laser pulses. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 94, 138–144 (2016)

Sellitto, , A., Cimmelli, V. A., Jou, D.: Mesoscopic Theories of Heat Transport in Nanosystems. In: SEMA-SIMAI Springer Series, vol. 6. Springer International Publishing (2016)

Kovács, R., Ván, P.: Generalized heat conduction in heat pulse experiments. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 83, 613–620 (2015)

Jun, Y.Y., Tian, X.-G., Xiong, Q.-L.: Nonlocal thermoelasticity based on nonlocal heat conduction and nonlocal elasticity. Eur. J. Mech. A Solid 60, 238–253 (2016)

Vázquez, F., Figueroa, A., Rodríguez-Vargas, I.: Nonlocal and memory effects in nanoscaled thermoelectric layers. J. Appl. Phys. 121, 014311 (2017)

Jou, D., Sellitto, A., Cimmelli, V.A.: Phonon temperature and electron temperature in thermoelectric coupling. J. Non-Equilib. Thermodyn. 38, 335–361 (2013)

Jou, D., Sellitto, A., Cimmelli, V.A.: Multi-temperature mixture of phonons and electrons and nonlocal thermoelectric transport in thin layers. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 71, 459–468 (2014)

Luzzi, R., Vasconcellos, A.R., Galvao-Ramos, J.: Predictive Statistical Mechanics: A Nonequilibrium Ensemble Formalism (Fundamental Theories of Physics). Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht (2002)

Lebon, G., Jou, D., Casas-Vázquez, J.: Understanding Non-equilibrium Thermodynamics. Springer, Berlin (2008)

Sellitto, A.: Crossed nonlocal effects and breakdown of the Onsager symmetry relation in a thermodynamic description of thermoelectricity. Physica D 243, 53–61 (2014)

Ruggeri, T., Sugiyama, M.: Rational Extended Thermodynamics beyond the Monatomic Gas. Springer International Publishing, Switzerland (2015)

Jou, D.: Relationships between rational extended thermodynamics and extended irreversible thermodynamics. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 378, 20190172 (2020)

Liu, I.-S.: Method of Lagrange multipliers for exploitation of entropy principle. Arch. Rational Mech. Anal. 46, 131–138 (1972)

Sellitto, A., Tibullo, V., Dong, Y.: Nonlinear heat-transport equation beyond fourier law: application to heat-wave propagation in isotropic thin layers. Continuum Mech. Thermodyn. 29, 411–428 (2017)

Straughan, B.: Heat Waves. Springer, Berlin (2011)

Ciarletta, M., Sellitto, A., Tibullo, V.: Heat-pulse propagation in functionally graded thin layers. Int. J. Engng. Sci. 119, 78–92 (2017)

Dubi, Y., Sivan, Y.: Hot electrons in metallic nanostructure-non-thermal carriers or heating? Light Sci. Appl. 8, 89 (2019)

Ruggeri, T., Lou, J.: Heat conduction in multi-temperature mixtures of fluids: the role of the average temperature. Phys. Lett. A 373, 3052–3055 (2009)

Ruggeri, T.: Multi-temperature mixture of fluids. Theoret. Appl. Mech. 36, 207–238 (2009)

Coco, M., Romano, V.: Assessment of the Constant Phonon Relaxation Time Approximation in Electron-Phonon Coupling in Graphene. J. Comput. Theor. Transp. 47, 246–266 (2018)

Mascali, G., Romano, V.: A hierarchy of macroscopic models for phonon transport in graphene. Physica A 548, 124489 (2020)

Yan, J., Zhang, Y., Kim, P., Pinczuk, A.: Electric field effect tuning of electron-phonon coupling in graphene. Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 166802 (2007)

Coco, M., Romano, V.: Simulation of electron-phonon coupling and heating dynamics in suspended monolayer graphene including all the phonon branches. J. Heat Trans. T. ASME 140, 092404 (2018)

Mascali, G., Romano, V.: Charge transport in graphene including thermal effects. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 77, 593–613 (2017)

Acknowledgements

All authors acknowledge the Italian National Group of Mathematical Physics (GNFM-INdAM), which supported the present research by means of the Progetto Giovani 2018/Heat-pulse propagation in FGMs and also funded the Progetto Giovani 2019/On a thermodynamically consistent reformulation of the Becker and Döring model for two-phase materials. A.S. also acknowledges the University of Salerno for the financial support under grants no. 300395FRB18SELLI and no. 300395FRB19SELLI.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Salerno within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sellitto, A., Carlomagno, I. & Di Domenico, M. Nonlocal and nonlinear effects in hyperbolic heat transfer in a two-temperature model. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 72, 7 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00033-020-01435-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00033-020-01435-0

Keywords

- Electron and phonon temperature

- Thermal wave propagation

- Acceleration wave

- Nonlocal and nonlinear effects