Abstract

This paper presents an analysis of the distribution of earthquake magnitudes for the period 1990–1998 in a broad area surrounding the epicenter of the 1995 Kobe earthquake. The frequency–magnitude distribution analysis is performed in a nonextensive statistical physics context. The nonextensive parameter q M , which is related to the frequency-magnitude distribution, reflects the existence of long-range correlations and is used as an index of the physical state of the studied area. Examination of the possible variations of q M values is performed during the period 1990–1998. A significant increase of q M occurs some months before the strong earthquake on April 9, 1994 indicating the start of a preparation phase prior to the Kobe earthquake. It should be noted that this increase coincides with the occurrence of six seismic events. Each of these events had a magnitude M = 4.1. The evolution of seismicity along with the increase of q M indicate the system’s transition away from equilibrium and its preparation for energy release. It seems that the variations of q M values reflect rather well the physical evolution towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

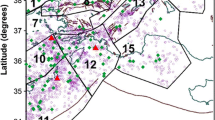

The Kobe (Hyogo-ken Nanbu) earthquake (M = 7.2) occurred on January 17, 1995 (5:46 a.m. Japan local time) in the southwestern part of Japan (Fig. 1a). This earthquake substantially damaged the city of Kobe and its surrounding areas claiming more than 6,000 lives (Kikuchi and Kanamori 1996).

In the present study we examine possible variations of the thermostatistical parameter q M related to the 1995 Kobe earthquake. This parameter, which is derived from the fragment-asperity model (Sotolongo-Costa and Posadas 2004), is related to the frequency-magnitude distribution and can be used as an index of the stability of a seismic area. The aforementioned model comes from first principles and describes the earthquake generation mechanism in a nonextensive statistical physics (NESP) framework (Tsallis 1988, 2009).

NESP was proposed by Tsallis (1988) and refers to the nonadditive entropy which is a generalization of Boltzmann–Gibbs (BG) statistical physics.

According to nonextensive formalism (Tsallis 2009 and references therein), entropy is given by \(S_{q} = k_{B} (1 - \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{W} {p_{i}^{q} } )/(q - 1)\), where k B is Boltzmann’s constant, p i is a set of probabilities and W is the total number of microscopic configurations. The nonadditive entropy Sq is proposed (Tsallis 2009) based on simple physical principles and multifractal concepts. The entropic index q introduces a bias in probabilities. Given that 0 < p i < 1, we have p q i > p i if q < 1, and p q i < p i if q > 1. Therefore, q < 1 enhances the rare events that have probabilities close to zero, whereas q > 1 enhances the frequent events having probabilities close to unity. Following (Tsallis 2009 and references therein) the proposed entropic form is based on p q i . In addition, the entropic form must be invariant under permutation. The simplest expression consistent with the latter statement is \(S_{q} = F(\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{W} {p_{i}^{q} } )\), where F(x) is a continuous function. Moreover, the simplest form of F(x) is the linear one. That leads to \(S_{q} = C_{1} + C_{2} \sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{w} {p_{i}^{q} }\). As any entropic expression Sq must be a measure of disorder. Thus, C 1 + C 2 = 0 (Tsallis 2009) and \(S_{q} = C_{1} (1-\sum\nolimits_{i = 1}^{W} {p_{i}^{q} } )\). In the limit q → 1 Sq approaches the Boltzmann–Gibbs entropy. The simplest way for this approach is when C 1 = k B /(q − 1). The index q has been interpreted as the degree of nonadditivity and is inherent in systems where many non-independent, long-range interacting subsystems, memory effects and (multi) fractality are present (Lyra and Tsallis 1998; Tsallis 2001; Vallianatos et al. 2011; Vallianatos 2012).

For any two probabilistically independent systems A and B Tsallis entropy satisfies \(\frac{{S_{\text{q}} (A + B)}}{k} = \frac{{S_{\text{q}} (A)}}{k} + \frac{{S_{\text{q}} (B)}}{k} + \left( {1 - q} \right)\frac{{S_{\text{q}} (A)}}{k}\frac{{S_{\text{q}} (B)}}{k}\). The last term on the right hand side of this equation brings the origin of nonadditivity.

NESP formalism has been applied in many nonlinear dynamical systems (Tsallis 2009) and seems an appropriate framework for the study of complex phenomena including various types of natural hazards such as earthquakes, forest fires and landslides (Vallianatos 2009). Recently, its applicability in seismicity from local (Michas et al. 2013; Vallianatos et al. 2012, 2013) to regional (Abe and Suzuki 2003, 2005; Telesca 2010a; Papadakis et al. 2013) and global scale (Vallianatos and Sammonds 2013) reveals its usefulness in the investigation of phenomena exhibiting nonlinearity, fractality and long-range interactions (Vallianatos and Telesca 2012; Vallianatos et al. 2012).

In general long-range correlations originate from two processes: the process’ memory (temporal correlations) and the process increments' “infinite” variance (heavy tails in the distribution). In this study we solely focus on the latter origin by employing NESP formalism.

Recent studies (Sarlis et al. 2010) based on natural time analysis (Varotsos et al. 2001, 2002), from which we deduce the maximum information from a given time series (Abe et al. 2005) and which identifies the critical time before the mainshock occurrence (Sarlis et al. 2008), reveal that a combination of nonextensivity with natural time analysis leads to results that satisfactorily describe the seismicity of Japan (Varotsos et al. 2011). In this study we focus on the variations of the nonextensive parameter prior to the Kobe earthquake.

Analysis of the magnitude distribution is performed for the period 1990–1998 in a broad area surrounding the epicenter of the 1995 Kobe earthquake. The temporal variations of q M values reveal a significant increase of the nonextensive parameter months before the Kobe earthquake. Moreover, the evolution of seismicity is consistent with the observed variations of the nonextensive parameter leading us to recover the main characteristics of the Kobe earthquake dynamics.

2 Data

The dataset used in this study concerns shallow earthquakes (focal depth, h ≤ 60 km) and is based on the earthquake catalog provided by the Japan University Network Earthquake Catalog (https://wwweic.eri.u-tokyo.ac.jp/CATALOG/junec/monthly.html––last accessed October 2013). It covers the period between 03:32:56.09 January 3, 1990 and 20:51:56.24 December 31, 1998 in the region spanning 34.35°N–35.60°N latitude and 134.00°E–136.00°E longitude (Fig. 1b). This corresponds to a total of 5,811 seismic events with threshold magnitude equal to m 0 = 2. The study area is chosen to be a large area surrounding the epicenter and the northeast trending earthquake clusters that define the physical evolution of seismicity related to the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Furthermore, the cluster method introduced by Reasenberg (1985) is used in this study for declustering of the earthquake catalog. This method identifies the aftershocks by linking earthquakes to clusters according to spatial and temporal interaction zones (VanStiphout et al. 2012). The spatial extent of the interaction zone is chosen according to stress distribution near the mainshock area. The temporal extent of the interaction zone is based on Omori’s law. Decluster analysis is performed using the ZMAP program (Wiemer 2001).

Several parameters are used for the declustering procedure. These parameters are chosen based on the results of the applied method and the effect of varying their values. The errors of the epicenter location and depth were taken to be equal to 1.5 and 2, respectively. The minimum value of the look-ahead time for building clusters, when the first event is not clustered (τmin), and the maximum value of the look-ahead time for building clusters (τmax) have been set equal to 0.5 day and 15 days, respectively. The probability of detecting the next clustered event (P 1) and the factor for the interaction radius of dependent events (R fact) have been set equal to 0.95 % and 10, respectively.

Figure 2 shows the time distribution of seismicity of the declustered catalog for the period 1990–1998. We observe the absence of earthquakes with magnitude M ≥ 4 between 1991 and 1993 and the occurrence of many significant events as we move towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake.

3 The Fragment-Asperity Model for Earthquakes: A Nonextensive Approach of the Frequency–Magnitude Distribution of Earthquakes

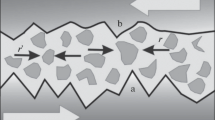

The fragment-asperity model for earthquakes was developed by Sotolongo-Costa and Posadas (2004) and describes the earthquake generation mechanism in an NESP context.

This model leads to the earthquake triggering mechanism considering the interaction between two rough surfaces (fault planes) and the fragments filling the space between them. Stress accumulates until a fragment is displaced or an asperity is broken resulting in fault plane slip and the release of energy. The aforementioned authors introduced an energy distribution function (EDF) that shows the influence of the size distribution of fragments on the energy distribution of earthquakes, including the Gutenberg-Richter law as a particular case. Furthermore, Silva et al. (2006) revised the fragment-asperity model and calculated an EDF that allows us to determine the relative number of earthquakes as a function of magnitude.

Telesca (2011) considered the relationship between magnitude (M) and released relative energy (ε) as:

and, taking into account the threshold magnitude m 0 (Telesca 2012), proposed a modified function that relates the cumulative number of earthquakes with magnitude, given as:

where M is the earthquake magnitude, m 0 is the threshold magnitude and A is proportional to the volumetric energy density.

The fragment-asperity model has been applied to various earthquake catalogs (Silva et al. 2006; Vilar et al. 2007; Telesca 2010a, b, c, 2011, 2012; Michas et al. 2013; Papadakis et al. 2013) including volcano related seismicity (Telesca 2010b; Vallianatos et al. 2013).

In the fragment-asperity model framework the nonextensive parameter q M informs us about the scale of interactions between the fault planes and the fragments (Matcharashvili et al. 2011; Papadakis et al. 2013; Telesca 2010b, c; Valverde-Esparza et al. 2012). Thus, the increase of q M indicates that the physical state of a seismic area moves away from equilibrium.

4 Results

In this study our interest concerns the temporal variations of the thermostatistical parameter q M during the period 1990–1998 in regards to the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Telesca (2010c) investigated the variations of this parameter regarding the seismicity of the L’Aquila area (central Italy) and estimated that the nonextensive parameter q M increases in a time interval starting days before the occurrence of the strong earthquake on April 6, 2009 (M L = 5.8).

Calculation of the nonextensive parameters q M and A is performed using the maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) method as this is proposed by Shalizi (2007) for the q-exponential (Tsallis) distributions and by Telesca (2012) for the earthquake cumulative magnitude distribution. Standard deviation and confidence intervals of the estimated parameters are calculated using the bootstrap method (Zoubir and Boashash 1998) by taking 500 bootstrap samples.

For the detection of possible variations of the nonextensive parameter q M we calculate Eq. (2) in different time windows. Figure 3 shows the q M variations over increasing (cumulative) time windows. The initial time window has a 400-event width increasing per 1 event. The cumulative estimate of the q M parameter reveals that on April 9, 1994 the parameter increases significantly indicating the start of a transition phase towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake. Moreover, the q M parameter peaks (q M = 1.5) during the Kobe earthquake and starts decreasing afterwards having a value equal to q M = 1.46 in 1997.

Furthermore, a more detailed inspection of Fig. 2 reveals the occurrence of an earthquake equal to M = 4.1 on April 9, 1994 followed by five more earthquakes of the same magnitude. Figure 4, which is a magnification of a portion of Fig. 2, shows occurrence of these seismic events between April 9, 1994 and April 13, 1994. We can clearly see (Figs. 3, 4) that there is agreement between the variations of q M values and the evolution of seismicity. Occurrence of many significant events with magnitude M > 4 breaks the seismicity pattern and this causes the increase of q M . Change in the values of the nonextensive parameter and in the seismicity pattern indicates a tendency for the physical state to move away from equilibrium.

Magnification of a portion of Fig. 2, showing six seismic events equal to M = 4.1 between April 9, 1994 and April 13, 1994

Figure 5 shows the variations of q M values over 200-event moving windows (overlapping) having a sliding factor equal to 1. As in the increasing (cumulative) time windows estimation (Fig. 3), the q M parameter increases significantly on April 9, 1994 and peaks (q M = 1.55) as we move towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake. After the strong event the nonextensive parameter starts decreasing rapidly.

Time variations of q M values (black continuous line) over 200-event moving windows (overlapping) having a sliding factor equal to 1 and the associated standard deviation (black dashed lines). On April 9, 1994 the nonextensive parameter increases significantly indicating the start of a transition phase towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake

Figure 6 shows the distribution of the relative cumulative number of earthquakes as a function of magnitude and the associated fitting curve according to Eq. (2) for the period between April 9, 1994 and January 16, 1995 (1 day before the 1995 Kobe earthquake). The nonextensive parameters are estimated equal to q M = 1.55 and A = 11.42, respectively. This high q M value also supports the fact that during this period the studied area is in a preparatory stage progressing to the strong event.

Normalized cumulative magnitude distribution and the fitting curve (black continuous line) according to Eq. (2) for the period between April 9, 1994 and January 16, 1995 (1 day before the 1995 Kobe earthquake). The nonextensive parameters are estimated equal to q M = 1.55 and A = 11.42, respectively. The dashed black lines indicate the 95 % confidence intervals

It should be noticed that Enescu and Ito (2001) studied the evolution of seismic activity and possible precursory changes associated with the 1995 Kobe earthquake and found a significant decrease of the fractal dimension (correlation dimension, D2) in 1994.

5 Conclusions

Using NESP the analysis of seismicity is performed in a broad region surrounding the 1995 Kobe earthquake for the period 1990–1998. In the framework of the fragment-asperity model the nonextensive parameter q M informs us about the physical state of the studied area.

This parameter reflects the scale of the interaction between fault planes and the fragments filling the space between them. Thus, as q M increases the physical state moves from equilibrium in a statistical physics sense.

For the examination of possible distinct variations of the nonextensive parameter q M we use different time windows (cumulative and moving windows). We detect a significant increase of the nonextensive parameter on April 9, 1994 which coincides with the occurrence of six seismic events equal to M = 4.1. The occurrence of these events breaks the magnitude pattern and along with the observed q M variations indicates a transition phase towards the 1995 Kobe earthquake.

It seems that the examination of q M variations in time is a useful index of the physical state of a seismic area and it becomes clear that using NESP, we can recover the main characteristics of the dynamic evolution of seismicity. The observed thermostatistical variations allows us to distinguish different dynamical regimes and to decode the physical processes towards a strong event. We conclude that for various study cases and for different tectonic regimes the analysis of the nonextensive parameter q M behavior in time is of crucial importance.

References

Abe, S., and Suzuki, N. (2003), Law for the distance between successive earthquakes, J. Geophys. Res. 108, 2113.

Abe, S., and Suzuki, N. (2005), Scale-free statistics of time interval between successive earthquakes, Physica A 350, 588–596.

Abe, S., Sarlis, N.V., Skordas, E.S., Tanaka, H.K., and Varotsos, P.A. (2005), Origin of the usefulness of the natural-time representation of complex time series, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 170601.

Enescu, B., and Ito, K. (2001), Some premonitory phenomena of the 1995 Hyogo-Ken Nanbu (Kobe) earthquake: seismicity, b-value and fractal dimension, Tectonophysics 338, 297–314.

Kikuchi, M., and Kanamori, H. (1996), Rupture process of the Kobe, Japan, earthquake of Jan. 17, 1995, determined from teleseismic body waves, J. Phys. Earth 44, 429–436.

Lyra, M.L., and Tsallis, C. (1998), Nonextensivity and multifractality in low-dimensional dissipative systems, Phys. Rev. Lett. 80, 53–56.

Matcharashvili, T., Chelidze, T., Javakhishvili, Z., Jorjiashvili, N., and Paleo, U.F. (2011), Non-extensive statistical analysis of seismicity in the area of Javakheti, Georgia, Comput. Geosci. 37, 1627–1632.

Michas, G., Vallianatos, F., and Sammonds, P. (2013), Non-extensivity and long-range correlations in the earthquake activity at the West Corinth rift (Greece), Nonlinear Proc. Geophys. 20, 713–724.

Papadakis, G., Vallianatos, F., and Sammonds, P. (2013), Evidence of nonextensive statistical physics behavior of the Hellenic subduction zone seismicity, Tectonophysics 608, 1037–1048.

Reasenberg, P. (1985), Second-order moment of central California seismicity, 1969–82, J. Geophys. Res. 90, 5479–5495.

Sarlis, N.V., Skordas, E.S., and Varotsos, P.A. (2010), Nonextensivity and natural time: The case of seismicity, Phys. Rev. E 82, 021110.

Sarlis, N.V., Skordas, E.S., Lazaridou, M.S., and Varotsos, P.A. (2008), Investigation of seismicity after the initiation of a seismic electric signal activity until the main shock, Proc. Jpn. Acad., Ser. B 84, 331–343.

Shalizi, C. R. (2007), Maximum likelihood estimation for q-exponential (Tsallis) distribution, arXiv:math/0701854v2 [math.ST] 1 February 2007, http://arxiv.org/pdf/math/0701854v2.pdf (last accessed January 2014).

Silva, R., Franca, G.S., Vilar, C.S., and Alcaniz, J.S. (2006), Nonextensive models for earthquakes, Phys. Rev. E 73, 026102.

Sotolongo-Costa, O., and Posadas A. (2004), Fragment-asperity interaction model for earthquakes, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 048501.

Telesca, L. (2010a), Analysis of Italian seismicity by using a nonextensive approach, Tectonophysics 494, 155–162.

Telesca, L. (2010b), Nonextensive analysis of seismic sequences, Physica A 389, 1911–1914.

Telesca, L. (2010c), A non-extensive approach in investigating the seismicity of L’ Aquila area (central Italy), struck by the 6 April 2009 earthquake (M L = 5.8), Terra Nova 22, 87–93.

Telesca, L. (2011), Tsallis-based nonextensive analysis of the southern California seismicity, Entropy 13, 1267–1280.

Telesca, L. (2012), Maximum likelihood estimation of the nonextensive parameters of the earthquake cumulative magnitude distribution, Bull. Seismol. Soc. Am. 102, 886–891.

Tsallis, C. (1988), Possible generalization of Boltzmann–Gibbs Statistics, J. Stat. Phys. 52, 479–487.

Tsallis, C., Nonextensive statistical mechanics and thermodynamics: Historical background and present status, In Nonextensive statistical mechanics and its applications, (eds. Abe. S. and Okamoto. Y.) (Springer, Berlin 2001) pp. 3–98.

Tsallis, C., Introduction to nonextensive statistical mechanics: approaching a complex world (Springer, Berlin 2009).

Vallianatos, F. (2009), A non-extensive approach to risk assessment, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 9, 211–216.

Vallianatos, F. (2012), On the non-extensive nature of the isothermal depolarization relaxation currents in cement mortars, J. Phys. Chem. Solids 73, 550–553.

Vallianatos, F., and Telesca, L. (2012), Statistical mechanics in earth physics and natural hazards, Acta Geophys. 60, 499–501.

Vallianatos, F., and Sammonds, P. (2013), Evidence of non-extensive statistical physics of the lithospheric instability approaching the 2004 Sumatran- Andaman and 2011 Honsu mega-earthquakes, Tectonophysics 590, 52–58.

Vallianatos, F., Triantis D., and Sammonds, P. (2011), Non-extensivity of the isothermal depolarization relaxation currents in uniaxial compressed rocks, Europhys. Lett. 94, 68008.

Vallianatos, F., Michas, G., Papadakis, G., and Sammonds, P. (2012), A non-extensive statistical physics view to the spatiotemporal properties of the June 1995, Aigion earthquake (M6.2) aftershock sequence (West Corinth rift, Greece), Acta Geophys. 60, 758–768.

Vallianatos, F., Michas, G., Papadakis, G., and Tzanis, A. (2013), Evidence of non-extensivity in the seismicity observed during the 2011–2012 unrest at the Santorini volcanic complex, Greece, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 13, 177–185.

Valverde-Esparza, S.M., Ramirez-Rojas, A., Flores-Marquez, E.L., and Telesca, L. (2012), Non-extensivity analysis of seismicity within four subduction regions in Mexico, Acta Geophys. 60, 833–845.

vanStiphout, T., Zhuang, J., and Marsan, D. (2012), Seismicity declustering, Community Online Resource for Statistical Seismicity Analysis, http://dx.doi.org/10.5078/corssa-52382934, Available at http://www.corssa.org (last accessed January 2014).

Varotsos, P.A., Sarlis, N.V., and Skordas, E.S. (2001), Spatio-temporal complexity aspects on the interrelation between Seismic Electric Signals and seismicity, Practica of Athens Academy 76, 294–321.

Varotsos, P.A., Sarlis, N.V., and Skordas, E.S. (2002), Long-range correlations in the electric signals that precede rupture, Phys. Rev. E 66, 011902.

Varotsos, P.A., Sarlis, N.V., and Skordas, E.S., Natural time analysis: The new view of time, Precursory seismic electric signals, earthquakes and other complex time series (Springer–Verlag, Berlin Heidelberg 2011) p. 285.

Vilar, C.S., Franca, G.S., Silva, R., and Alcaniz J.S. (2007), Nonextensivity in geological faults, Physica A 377, 285–290.

Wiemer, S. (2001), A software package to analyse seismicity: ZMAP, Seismol. Res. Lett. 72, 373–382.

Zoubir, A.M., and Boashash, B. (1998), The bootstrap and its applications in signal processing, IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 15, 55–76.

Acknowledgments

G. Papadakis acknowledges the financial support from the Greek State Scholarships Foundation (IKY). This work has been accomplished in the framework of the postgraduate program and co-funded through the action “Program for scholarships provision I.K.Y. through the procedure of personal evaluation for the 2011–2012 academic year” from resources of the educational program “Education and Life Learning” of the European Social Register and NSRF 2007–2013.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Papadakis, G., Vallianatos, F. & Sammonds, P. A Nonextensive Statistical Physics Analysis of the 1995 Kobe, Japan Earthquake. Pure Appl. Geophys. 172, 1923–1931 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-014-0876-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-014-0876-x