Abstract

Background

Transition to clerkship courses bridge the curricular gap between preclinical and clinical medical education. However, despite the use of simulation-based teaching techniques in other aspects of medical training, these techniques have not been adequately described in transition courses. We describe the development, structure and evaluation of a simulation-based transition to clerkship course.

Approach

Beginning in 2012, our institution embarked upon an extensive curricular transformation geared toward competency-based education. As part of this effort, a group of 12 educators designed, developed and implemented a simulation-based transition course. The course curriculum involved seven goals, centered around the 13 Association of American Medical Colleges Core Entrustable Professional Activities for entering residency. Instructional techniques included high-fidelity simulation, and small and large group didactics. Student competency was determined through a simulation-based inpatient-outpatient objective structured clinical examination, with real-time feedback and remediation. The effectiveness of the course was assessed through a mixed methods approach involving pre- and post-course surveys and a focus group.

Evaluation

Of 166 students, 152 (91.6%) completed both pre- and post-course surveys, and nine students participated in the focus group. Students reported significant improvements in 21 out of 22 course objectives. Qualitative analysis revealed three key themes: learning environment, faculty engagement and collegiality. The main challenge to executing the course was procuring adequate faculty, material and facility resources.

Reflection

This simulation-based, resource-heavy transition course achieved its educational objectives and provided a safe, supportive learning environment for practicing and refining clinical skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

After calls for reform in the early 20th century, the Flexner Report standardized undergraduate medical education in the United States [1]. Based on Flexner’s 2 × 2 “Hopkins” model, the first two ‘preclinical’ years are spent primarily in the classroom, while the second two ‘clinical’ years are focused on clinic- and hospital-based rotations, or clerkships. This front-loaded didactic model came at the expense of meaningful interaction with patients prior to clerkships. Consequently, the lack of clinical experience early in training has made the transition period to the clinical environment stressful for learners and clerkship directors [2, 3]. To alleviate this stress and to better prepare students for the clinical realm, many medical schools have implemented a transition to clerkship course [4,5,6].

Traditional transition to clerkship courses focus largely on workplace-based skills, such as oral presentations, hospital and clinic logistics, student roles and responsibilities, and more recently, use of the electronic medical record [4, 5]. In a large 2010 study of US and Canadian medical schools, 88% of schools reported having a transition course [4]. However, only 35% of these courses issued a course grade (including pass/fail), and only 41% included evaluations of student performance. Didactic sessions were present in 98% of courses, hands-on practice in 74%, and clinical immersion in only 21%. While this study did not define the type of ‘hands-on’ training, simulation-based teaching techniques were likely used in many of the courses. The authors concluded that transition to clerkship courses should incorporate real clinical settings, emphasize hands-on practice of clinical skills, and formalize evaluations.

Transition to residency and graduate medical education courses have leveraged high- and low-fidelity simulation extensively over the past 20 years [7,8,9]. However, comparable literature is lacking for the use of simulation in transition courses. Since medical students are often excluded from many aspects of primary patient management (e.g. procedures), simulation provides a modality to develop important clinical skills without risk to patients. Additionally, given patient safety concerns—particularly involving vulnerable populations—some have gone as far as mandating simulation-based education as an ethical imperative [10]. Regardless, multiple studies involving many different types of learners have shown compelling benefits from simulation-based education and, hence, incorporation of simulation-based education into transition courses seems justified [9, 11]. Additionally, simulation provides the opportunity for deliberate practice, which has been described as an essential element for the development of expertise [12]. This concept was displayed in a recent article by Ryan et al., where student performance on clinical rotations significantly improved following implementation of a transition course involving a significant simulation component [13].

Accordingly, during a comprehensive curriculum transformation of undergraduate medical education at our institution, we incorporated high-fidelity simulation into a new transition to clerkship course. This new course serves as a ‘gateway’ between preclinical and clinical phases of training, preparing students for their expanded roles on clinical rotations. The purpose of this report is to describe the development, structure and evaluation of this course.

Approach

Beginning in 2012, our institution embarked upon an extensive transformation of the undergraduate medical curriculum [14]. The curriculum was divided into two phases: foundational (first 18 months) and clinical experiences (19–48 months). Although weekly clinical skills labs and preceptorships were incorporated during the foundational stage, curriculum developers perceived a need for a transition course to bridge the curricular gap between the foundational and clinical phases of training, as well as to provide learners with a psychological demarcation of their transition to full-time, immersive clinical training. Curriculum developers used the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Core Entrustable Professional Activities (EPAs)[15, 16] framework, as well as evidence from transition courses, simulation-based education [4, 5, 9], and the expertise literature [12], in designing the course.

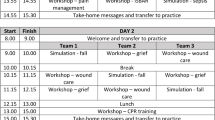

The first transition to clerkship course was held in 2016, and has evolved since then with iterative improvements adopted from learner and teacher feedback. Specifically, we have incorporated more senior medical student teachers into teaching sessions and reduced the number of times the course is offered from twice to once a year, thus saving considerable resources. Two weeks in duration, the course has seven goals, each with associated objectives and educational and assessment strategies (Tab. 1). Instruction for each goal involves a combination of pre-work (e.g. videos, readings, reflections), and large and small group sessions, including high-fidelity simulation. Students are taught the content during the first week, and are assessed during the second week with a comprehensive inpatient-outpatient objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) (Tab. 1 and Supplemental Tab. 1). The course is graded as pass/fail.

The OSCE involves both adult and pediatric cases that progress between inpatient and outpatient settings (Supplemental Tab. 1 and Supplemental Fig. 1). Whereas in the first week of the course skills associated with each goal are taught individually, in the OSCE these skills are integrated into a continuous case. Students begin the OSCE in either the outpatient or inpatient setting, and then proceed to the other setting upon scenario completion, following the same simulated patient (Supplemental Fig. 1). Standardized rubrics are used to assess performance in both the inpatient (Supplemental Fig. 2) and outpatient (Supplemental Figs. 3 and 4) scenarios. Students are graded by faculty and standardized patients. Students who do not achieve a passing score for any of the components of the OSCE using the standardized rubrics are remediated in real-time. Remediation is done by a faculty member or the course director. Students must display adequate knowledge, skills or attitudes in the particular element(s) they failed. At the end of the inpatient portion of the OSCE, students are debriefed in small groups by an instructor and key learning points are emphasized.

In 2019, students taking the course completed a pre- and post-course survey to assess comfort level with the objectives of the course. The post-course survey also solicited open feedback about the course in a free-text format. Because data were ordinal and many measures exhibited pre- and post-changes in skew, pre- and post-course quantitative results were calculated using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests using SPSS (IBM, version 25). Qualitative analysis was performed by two senior authors using directed qualitative content analysis [17]. Themes were developed independently, then combined and collated. Exemplar comments were chosen to emphasize each theme. Nine months after the completion of the course, a 1-hour focus group was conducted by two senior authors to validate themes from the qualitative analysis.

Our Institutional Review Board deemed the study exempt from review.

Evaluation

Of 166 medical students enrolled in transition to clerkship in 2019, 152 completed both pre- and post-course surveys for a response rate of 91.6%. Nine students (5 males, 4 females) participated in the post-course focus group, and two sets of field notes were taken independently by two senior authors, collated and used for validation and clarification of qualitative themes. Post-course means were significantly higher than pre-course means for 21 out of 22 objectives, reflecting improved confidence in skills taught during the course (Supplemental Tab. 2).

Qualitative content analysis revealed three main themes: learning environment, faculty engagement and collegiality (Tab. 2). Within the learning environment theme, 4 sub-themes were identified: hands-on/active learning, pertinent skills for clinical practice, pertinent skills for the clinical environment, and course/session structure.

Reflection

Curricular reform, directed toward competency-based educational outcomes, is a current priority of many medical schools, including ours [14]. The utilization of simulation-based teaching techniques in this course, including the use of a multi-structured OSCE, was helpful in teaching and assessing competency in key areas of clinical practice, and providing real-time feedback and remediation. The course was well received by learners, who demonstrated increased confidence levels in most objectives, and remarked positively on the use of simulation techniques in teaching content. Students also reported positively on the supportive role of faculty and the ability to connect with peers through small group sessions.

The use of a high-stakes, multi-structured OSCE was unique to our course, and helped address the concern raised by O’Brien et al. in terms of the lack of student evaluations in 41% of transition courses [4]. In line with the aims of the AAMC Core EPA project [16], the OSCE ensured that students could display a certain threshold of competence in key aspects of clinical care prior to entering the clinical environment, thus aiding in a successful transition. Students who did not reach passing thresholds on the OSCE were provided immediate feedback and remediation in a nonjudgmental environment with the opportunity to repeat testing until competence had been demonstrated. As confirmed by feedback during the focus group, the pass/fail grading structure, with real time remediation, helped decrease anxiety among students, and enhanced learning in a ‘safe’ environment. Furthermore, the use of evidence-based evaluation tools was helpful in standardizing formative and summative evaluations of student performance, particularly in regards to oral presentations [18].

Given the nature of high-fidelity simulation, our course requires significant faculty, material and facility resources. For example, the 2019 course utilized 66 different facilitators, 5 high-fidelity simulation rooms for 6–8 h per day over 8 days, and 12 standardized patients, each with a simulation examination room, for 8 h per day over 4 days. Since this course was designed within the construct of our school’s curriculum transformation, we have been fortunate to receive considerable support from our educational administration in meeting these needs. However, recruitment of faculty for the many teaching components remains a challenge. To address this challenge, we have begun using senior medical students to teach some elements, including scrubbing/gowning/gloving, and giving oral presentations. In the future, we plan to implement a specific ‘teaching elective’ for senior medical students, which will allow them a more formal role in teaching and modifying the course to suit the needs of learners. In institutions with resource limitations, many of the sessions could be conducted with lower fidelity technology and/or incorporate more peer-to-peer teaching and team-based learning approaches.

Our study had several important limitations. First, since the study was conducted within a single medical school, the results may not be generalizable to other settings. Second, quantitative outcomes were based on self-assessment of student comfort level with individual tasks and, therefore, may be less reliable than objective measures of competence. Third, outcomes were recorded for one academic year and, therefore, sampling bias may affect results. Sampling over multiple years would also help determine the efficacy of iterative changes made to the course. Finally, beyond the focus group, follow-up data were not obtained to examine whether the course facilitated students’ performance in their clinical rotations. Future research into clinical performance outcomes from transition to clerkship courses is needed.

References

Cooke M, Irby DM, Sullivan W, Ludmerer KM. American medical education 100 years after the Flexner report. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1339–44.

Godefrooij MB, Diemers AD, Scherpbier AJ. Students’ perceptions about the transition to the clinical phase of a medical curriculum with preclinical patient contacts; a focus group study. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10:28.

Windish DM, Paulman PM, Goroll AH, Bass EB. Do clerkship directors think medical students are prepared for the clerkship years? Acad Med. 2004;79:56–61.

O’Brien BC, Poncelet AN. Transition to clerkship courses: preparing students to enter the workplace. Acad Med. 2010;85:1862–9.

Poncelet AN, O’Brien BC. Preparing medical students for clerkships: a descriptive analysis of transition courses. Acad Med. 2008;83:444–51.

O’Brien B, Cooke M, Irby DM. Perceptions and attributions of third-year student struggles in clerkships: Do students and clerkship directors agree? Acad Med. 2007;82:970–8.

Teo AR, Harleman E, O’Sullivan PS, Maa J. The key role of a transition course in preparing medical students for internship. Acad Med. 2011;86:860–5.

Bradley P. The history of simulation in medical education and possible future directions. Med Educ. 2006;40:254–62.

Maran NJ, Glavin RJ. Low- to high-fidelity simulation—a continuum of medical education? Med Educ. 2003;37(Suppl 1):22–8.

Ziv A, Wolpe PR, Small SD, Glick S. Simulation-based medical education: an ethical imperative. Acad Med. 2003;78:783–8.

Lammers RL. Simulation: the new teaching tool. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:505–7.

Ericsson KA. Deliberate practice and acquisition of expert performance: a general overview. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:988–94.

Ryan MS, Feldman M, Bodamer C, Browning J, Brock E, Grossman C. Closing the gap between preclinical and clinical training: impact of a transition-to-clerkship course on medical students’ clerkship performance. Acad Med. 2019; https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002934.

Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S):S42–S8.

Englander R, Aschenbrener CA, Call SA, et al. Core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. 2014. https://www.mededportal.org/icollaborative/resource/887. Accessed 21 June 2019.

Englander R, Flynn T, Call S, et al. Toward defining the foundation of the MD degree: core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. Acad Med. 2016;91:1352–8.

Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–88.

King MA, Phillipi CA, Buchanan PM, Lewin LO. Developing validity evidence for the written pediatric history and physical exam evaluation rubric. Acad Pediatr. 2017;17:68–73.

Acknowledgements

In addition to the many educators, coordinators and simulation staff who teach in the Transition to Clinical Experiences course each year, the authors wish to thank several of the initial developers and supporters of the course, including: Drs. Judy Bowen, Marian Fireman, Jeff Kraakevik, Bart Moulton, Meg O’Reilly, Jennifer Rossi, and Ms. Janet Wheeler.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

J.P. Austin, M. Baskerville, T. Bumsted, L. Haedinger, S. Nonas, E. Pohoata, M. Rogers, M. Spickerman, P. Thuillier and S.H. Mitchell declare that they have no competing interests.

Caption Electronic Supplementary Material

40037_2020_590_MOESM6_ESM.docx

Supplemental Table 2: Means (and Standard Deviations) for Student Scores on the Self-Assessment Survey of Transition to Clerkship Objectives: Pre-versus Post-Course

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Austin, J.P., Baskerville, M., Bumsted, T. et al. Development and evaluation of a simulation-based transition to clerkship course. Perspect Med Educ 9, 379–384 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00590-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-020-00590-4