Abstract

The Job Demands-Resources Framework (JDR) has established job- and personal resources as essential elements motivating people to perform. Whilst the purpose of job resources in this motivational process is well established, the role of personal resources is still quite ambiguous. Within the JDR framework, personal resources could (a) directly affect performance, (b) indirectly affect the relationship between a job resource and a performance outcome and (c) moderate the job resource-performance relationship. Grit has recently emerged as a promising personal resource as it could potentially act as a direct antecedent-, mediator and moderator within the motivational process of the JDR. To further the debate on the role of personal resources, this paper explores the function of grit (as a personal resource) within the person-environment fit (job resource) and task performance relationship. Specifically, the aim is to determine if grit directly or indirectly affects the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. Finally, it aims to investigate whether grit moderates this relationship. Data were collected from 310 working adults through electronic surveys, and the relationships were explored through structural equation modelling. When controlling for age and gender, the results showed a positive association between person-environment fit, grit and task performance. Further, grit was also found to indirectly affect the relationship between the person-environment fit and task performance. However, no moderating effect could be established. This signifies the importance of grit as a psychological process, rather than a buffering element that may explain how person-environment fit affects performance outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Growing global economic uncertainty and volatility have placed more pressure on organizations to enhance business growth to ensure long-term financial stability (Kok & Van Den Heuvel, 2019). Business growth is dependent upon several factors but is primarily influenced by the proficiency of employees to perform the most essential, core or substantive tasks central to their jobs on time and to specification (i.e. employees’ task performance: Koopmans et al., 2012). Employees are therefore encouraged to increase the efficiency of these work-related tasks to meet ever-stretching organizational growth goals and financial targets (Mishra et al., 2021). This in-role, task-related performance is thus an essential operational metric that organizations attempt to quantify, measure, predict and actively manage (Koopmans et al., 2012). Therefore, it is not surprising that a great deal of research has emerged that attempts to explain the factors that hinder and facilitate in-role task performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

Popular work psychological models such as the Demand-Control model (Karasek, 1979) and the Job Demands-Resources Framework (JDR: Demerouti et al., 2001) have thus emerged as dominant explanatory frameworks which attribute task performance as a function of employees’ work environments or “job characteristics” (i.e. job demands/job resources). According to the JDR framework, task performance is an outcome of a balance between the negative- (job demands) and positive- (job resources) aspects of one’s work environment (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). From this perspective job demands refer to the physical-, social-, or organizational aspects of a job that require enduring effort and are associated with lasting physical/psychological costs (e.g. work-load or work-pressure: Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). In contrast, job resources refer to those physical, social, or organizational aspects of the job that are important to (a) facilitate organizational goals, (b) reduce demands, strain, and the physical/psychological costs of work and (c) stimulate personal growth and development (e.g. person-environment fit: Schaufeli, 2017). These job characteristics affect individual and organizational performance through both a health impairment- and a motivational process (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017).

According to Bakker and Demerouti (2017), the health impairment process involves high job demands and insufficient resources that gradually drain individuals’ mental energies, leading to poor health/wellbeing and performance outcomes over time. High job demands would inevitably lead to increased stress and strain, negatively affecting employees’ mental health and the efficiency of completing work-related tasks (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). In contrast, the motivational process is activated in the presence of an abundance of available job resources, leading to greater engagement, organizational commitment, and task performance (Schaufeli & Taris, 2014). Employees are, therefore, motivated to perform because they possess the necessary resources required to derive more fulfilment from work (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). In addition to the direct effects of job resources on performance within the motivational process, it also acts as a buffer against the harmful effect job demands have on strain and stress (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017). The motivational process thus serves a dual purpose by explaining the factors facilitating the positive- and those buffering against the negative effects that hinder performance (Teuber et al., 2021). Therefore, the motivational process is an important route to consider when organizations want to promote or facilitate task performance.

There is still, however, an ongoing debate and contention as to the underlying explanatory mechanisms describing how or why job resources translate into performance and the factors that buffer/strengthens this relationship (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Bakker & De Vries, 2021; Mazzetti et al., 2021; Schaufeli & Taris, 2014; Teuber et al., 2021). Various attempts have been made to explain such from a work-characteristics perspective. However, Xanthopoulou et al. (2007) argued that personal resources might play an essential role in this debate. Personal resources are defined as the states (e.g. hope and optimism), traits (e.g. grit and personality), behaviours (e.g. deliberate practice), and mental abilities (e.g. resilience) people activate to increase the control they have over their environment and to improve the perceived fit between the person and the job (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Where job resources refer to a job’s contextual or environmental factors, personal resources are more concerned with the individual characteristics influencing work or explaining how work environments impact or lead to organizational outcomes (Schaufeli, 2017). Bakker and Demerouti (2017) also argued that there is a direct, reciprocal relationship between job- and personal resources, where the availability of the former might influence the experience of the latter (and vice versa). Personal resources could therefore play a similar role as job resources within the motivational process of the JDR. Personal resources could potentially fulfil three roles by (a) directly affecting task performance, (b) acting as a means to explain how job resources translate into task performance or (c) magnifying the effect job resources have on task performance (Bakker & Demerouti, 2017; Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). In other words, personal resources “may function either as moderators or as mediators in the relationship between environmental factors and organizational outcomes or may even determine the way people comprehend the environment, formulate it and react to it” (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007, p. 124).

Previous research has generally supported the three potential roles of personal resources within the motivational process of the JDR. For example, Kodden and Hupkes (2019) found that personal resources (self-efficacy, resilience and optimism) directly related to coaching performance (but did not mediate the relationship between job resources and performance). Similarly, psychological capital as a personal resource (hope, optimism, resilience and self-efficacy) was a strong predictor of various forms of self-report- and actual performance metrics across different studies, samples, contexts (Luthans et al., 2007) and times (Peterson et al., 2011). As a mediator, Xanthopoulou et al. (2007) found that personal resources affected the perception of job resources and mediated the relationship between job resources and performance outcomes. However, they could not confirm the originally hypothesized moderating effect of various personal resources on the relationship between job characteristics and important organizational metrics. Similarly, grit (as a personal resource) was also found to mediate the relationship between person-environment fit and performance within a sample of working adults (Vogelsang, 2018). Further, certain personality characteristics like self-directedness (as a trait level personal resource) were also found to mediate the relationship between job resources (i.e. responsibility) and performance (c.f. Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). As a moderator , Van Yperen and Snijders (2000) found that general self-efficacy (as a personal resource) moderated the relationship between demands and mental health. Similarly, Jumat et al. (2020) also found that grit moderated the relationship between resources and mental health outcomes. However, other studies could not establish the moderating effect of personal resources between job characteristics and performance outcomes (Xanthopoulou et al., 2007). Personal resources seem to play an important part in the motivation process, but their role within the JDR model is still empirically unclear and ill-defined (Schaufeli et al., 2017; Teuber et al., 2021).

Taken together, job- and personal resources are deemed essential elements required for motivating people to increase their task performance at work. The role personal resources play within the motivational process of the JDR is still ambiguous and may be dependent on several factors ranging from the type of job/personal resources measured, to the context of the sample population. To further explore the motivational process of the JDR model, the potential (differential) functions of personal resources within the JDR’s motivational process should be tested. To test the three potential roles of personal resources within the motivational process, we posit that two well-established predictors of task performance could act as potential antecedents: Person-Environment Fit as a job- (i.e. the match between personal characteristics and the requirements of the work environment: Schaufeli, 2017) and Grit as a personal resource (i.e. showing long-term interest in and a high level of perseverance in pursuing important goals: Teuber et al., 2021).

Person-environment fit and task Performance: A job resource perspective

Employees invest considerable time and energy in seeking a job that matches their qualifications, needs, goals and values. At the same time, organizations invest substantial effort and financial resources into selecting applicants who fit the job- and the organizational environment (van Vianen, 2018). The match between characteristics or attributes of individuals and their work environment attributes is, therefore, an important job resource (Schaufeli, 2017) and is commonly referred to as person-environment fit (Kristof-Brown and Guay, 2011). Person-environment fit is loosely defined as the congruence or similarity between the individual’s personal characteristics and the expectations from the organizational environment in which he/she functions (Edwards & Shipp, 2007). Although various conceptualizations of person-environment fit exist within the literature, Cable and DeRue’s (2002) approach is the most prolifically used. Cable and DeRue (2002) argued that person-environment fit is a function of (a) a fit between an employee’s values and the organization’s culture (Person-Organization Fit), (b) congruency between an individual’s needs and the rewards received for their service (Need-Supply Fit), and (c) a match between the requirements of the job and the skill set of the individual (Demand-Ability Fit). This alignment between the characteristics of the person (i.e. personality, work preferences, signature strengths, professional capabilities, values etc.) and the requirements from their environment (i.e. task demands, organizational culture, job attributes etc.) accounts for significant interindividual differences in task performance (Armitage & Amar, 2021; Lauver & Kristof-Brown, 2001).

A high level of alignment or ‘fit’ between the person and the organizational environment would make people feel more connected and committed to the organization, enhancing their performance in work tasks (Armitage & Amar, 2021). This congruence may also positively affect an individual’s decision to join or stay with a given organization and whether or not extra-role behaviours will be expressed at work (Zwider et al., 2015). When a lack of fit occurs, individuals are more likely to leave the organization and may decrease their in-role performance (O’Reilly et al., 1991). When the organization fulfils the needs of the individual, and the individual fulfils the need of the organization, it promotes optimal conditions for employees to gain more job knowledge and skills, which in turn aids them in performing better in their roles (Greguras & Diefendorff, 2009; Hunter, 1983). Employees who experience that their needs, values and expectations are aligned with those of the organization, will perceive a positive work environment that is conducive to performance (Redelinghuys et al., 2019).

The Person-Environment Fit-Performance relationship is thus well established in the literature. Previous research have reported a positive direct relationship between person-environment fit and various forms of performance (Hoffman & Woehr, 2006; Van Zyl et al., 2022) which were partially mediated by various work-related attitudes or behaviours (Arthur et al., 2006). Dawis (2005) postulated that the performance benefits of an excellent person-environment fit occur because the rewards received within (or because of) the role corresponds to the values the individual seeks to match through their tasks. A good fit thus leads to more implicit and explicit rewards from the organization, which in turn incentivizes further performance (Kristof-Brown et al., 2005). Therefore, person-environment fit is an important job resource to consider in designing work and should be central to an organizations’ recruitment, selection, and talent management strategy (Redelinghuys et al., 2019).

However, the theory of work adjustment postulates that there can never be a perfect fit between the individual's characteristics and the work environment's requirements (Dawis, 2005). This may be due to either individual- (e.g. someone choosing the wrong career) or organizational factors (e.g. employers selecting the wrong candidate). Person-environment fit may change over time as skills and abilities develop, leading to feelings that one has outgrown a role or because priorities change due to non-work commitments (Chi et al., 2020). Similarly, the nature of the work-role or the types of rewards received may change over time and thus no longer meet the needs of the individual (Dawis, 2005). Individuals will, therefore, inevitably adjust either their physical work environment or their abilities/values/characteristics to compensate- or correct for this lack of fit as a means to return to their previous levels of performance (Chi et al., 2020). Dawis (2005) argued that the flexibility of the individual or the organization would ultimately impact the extent to which employees are willing and able to tolerate a poor person-environment fit. The level of flexibility will vary between individuals but is largely influenced by internal factors or ‘personal resources’ such as personality traits, resilience, strengths-use, self-efficacy, environmental mastery, hope and optimism (Dawis, 2005; Van Zyl et al., 2020a, b). Therefore, activating these personal resources is a means to compensate for the perceived lack of fit, which negatively impacts their performance (Ayoko & Ashkanasy, 2019). This leads to the question of whether other personal resources (such as grit) could buffer against the negative or enhance the positive impact (a poor) person-environment has on employee performance.

Additionally, when the lack of congruence between the person and the work environment is greater than one’s flexibility, it leads to either active adjustment behaviours (i.e. trying to change work environments physically), reactive adjustment behaviours (i.e. changing personal characteristics or to better suite the environment) or leads to increased levels of perseverance (i.e. extent to which individuals will try to adjust or push through negative situations before giving up: Davis, 2005). Perseverance is of particular importance, as it is a personal characteristic which is directly affected by person-environment fit. Ayoko and Ashkanasy (2019) argued that perseverance is not just an outcome of poor fit (i.e. to close the expectations gap), but can also be caused by good fit (i.e. to keep receiving rewards). When there is a good person-environment fit, individuals would view organizational goals as their own and are therefore more willing to push through difficult situations to achieve such. This, in turn, helps increase their performance and the rewards they receive (Dawis, 2005). Given that perseverance is considered a trait-like personal characteristic within the JDR framework (and that it is a core component of grit), we postulate whether a direct relationship between person-environment fit and personal resources exists.

Because environmental factors seem to affect aspects of trait-like personal resources, we further explore the theoretical reasoning behind such. Drawing from the demand-control model, Wu (2016) found that work environments/experiences are driving factors for changes in personality over time. Given that work plays such a central part in the human condition and identity formation, work experiences inevitably shape individuals’ values, social roles and daily activities (Van Zyl et al., 2010). Over time, a perceived lack of fit with the organizational environment will shape how individuals think, feel and function which gradually changes aspects of one’s personality (Frese, 1982; Li et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2015). This change in personality is the result of individuals’ attempts to change their ways of thinking/feeling/behaving as a means to close the gap between their characteristics and the demands of the environment (Li et al., 2014; Savickas, 1997, 2005; Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2015). This notation is further supported by Gary’s biopsychological theory of personality (1981; 1990), which states that this because the two systems governing personality change through behaviour and emotion (the behavioural inhibition system and the behavioural activation system) are sensitive to the punishments or rewards received by the organization for a perceived fit or misfit. When individuals close the gap between their individual characteristics and the requirements of the environment, they are rewarded with praise or incentives indicating that no further change is necessary (Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2015). If the gap remains, the associated punishment would force further corrective action and lead to significant changes in personality traits over time (Li et al., 2014; Savickas, 1997, 2005; Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2015). In both scenarios, when the needs and values of the organization are closely aligned to those of the individual, employees start to feel that organizational goals are “their” goals (Wang & Wu, 2021). This means that people are more likely to show a deeper interest in work-related activities and thus more likely to persevere at work and perform (Wang & Wu, 2021; Wu, 2016). According to Bolger and Zuckerman (1995), it is possible that job characteristics (such as person-environment fit) may lead to changes in trait-like personal resources or stable characteristics, impacting performance over time. This leads to the question whether person-environment fit as a job resource could lead to changes in trait-like personal resources (such as grit) and if these changes in turn explain performance.

Grit and task performance: A personal resource perspective

In line with the conservation of resources theory (Hobfoll, 1989), grit can be seen as a personal resource describing a personal characteristic, condition or energy that supports the attainment of work and life goals. Apart from matching the inherent requirements of a job, employees need to show long-term passion for and dedication to their work-related tasks to ensure sustainable performance (Duckworth et al., 2007). In essence, employees should show “grit”. To have grit means staying focused and dedicated to achieving long-term goals, despite obstacles and adversity (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). Grit is an intrapersonal, non-cognitive psychological construct and signature strength that, according to Duckworth et al. (2007), comprises two components: (a) consistency of interest in long-term goals and (b) perseverance of effort exerted in achieving these goals. From Duckworth et al.’s (2007) perspective, consistency of interest enables motivated engagement in- or the predisposition for continuously re-engaging with a particular class of tasks, events, or ideas over time (Hidi & Renninger, 2006). Consistency in interest fuels the development of self-efficacy or a sense of mastery in the tasks one performs (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009). On the other hand, perseverance focuses on continued activity despite setbacks, failures, or proverbial roadblocks (Duckworth et al., 2007). Gritty individuals do not often change their goals or interests and will work tirelessly to achieve such, even when faced with significant setbacks (Credé, 2018).

Grit has shown to be an essential element required to induce various positive individual- and organizational performance-related outcomes. For example, gritty students perform better in both high school and university courses, show higher academic throughput rates and are more committed to their educational goals (Duckworth and Quinn, 2009; Vinson et al., 2022). Crede (2018) reported that gritty individuals are more committed to their relationships, achieve greater career successes, show more scholastic achievement, are more committed to work and are more likely to complete personal/professional goals. Gritty employees show less counterproductive work behaviours (Creschi et al., 2016), are more engaged at work (Azari Noughabi et al., 2022) and report higher levels of psychological wellbeing (Salles et al., 2014). Further, those who report higher levels of grit are more likely to meet sales targets, may be more innovative and perform better at work-related tasks (Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014; Van Zyl et al., 2022).

As such, gritty individuals tend to be high achievers in their domains of interest, even outperforming their intellectually gifted peers (Credé, 2018). Employees with higher grit levels are more likely to perform because they are better prepared to use their strengths to complete tasks, are less influenced by setbacks, and invest sustained energy in achieving their goals (Duckworth, 2016). Unlike other trail-like personal resources such as self-control, conscientiousness and self-regulation that have been associated with task performance, grit does not merely aid in resisting short-term temptations/distractions but rather aids individuals to persist in their efforts or endure challenges over the longer term (Jachimowicz et al., 2018; Kim & Lee, 2015). Further, from the perspective of the JDR framework, grit also aids employees in managing work pressure more effectively (Van Zyl et al., 2020a, b). Gritty employees are able to offset the negative impact of their high job demands, and a lack of job-related resources, on their performance at work (Van Zyl et al, 2020a, b). When confronted with high demands and low resources, Probst et al. (2021) propose that employees with higher grit levels are more likely to explore a mutually beneficial exchange relationship with their employer to manage these demands more actively. Grit can therefore aid employees in persisting through or enduring their highly volatile, uncertain or demanding work environments (Credé, 2018; Kim & Lee, 2015) and is an essential antecedent of performance (Van Zyl et al., 2020a, b, 2022).>

The role of grit in the person-environment fit – performance relationship

Taken together, the literature supports the notion that grit could potentially play multiple roles in explaining the person-environment fit and task performance relationship. First, person-environment fit and grit are seen as direct antecedents of task-related performance. If a substantial match or “fit” occurs between the individual’s characteristics (personality, strengths, needs and abilities) and the environment in which he/she functions, he/she is likely to perform better in work-related tasks (Van Zyl et al., 2010). In other words, if individuals’ work-related preferences/strengths are matched to the job’s requirements (person-environment fit), the possibility for performance increases (Richter et al., 2021; Van Zyl et al., 2020a, b). Further, when employees show high levels of interest in work-related tasks and demonstrate perseverance in the execution of such (grit), they are more likely to perform well in work-related tasks (Credé, 2018). Therefore, grit is also directly associated with task performance.

-

Hypothesis 1: Grit and person-environment fit are directly and positively related to task performance.

Second, grit could also potentially act as a mediating mechanism that explains how person-environment translates into task performance. If individuals perceive themselves to be a good ‘fit’ for the organization, they intrinsically attribute work-related goals as ‘personal goals’ and could therefore show enduring passion and perseverance in achieving them (Wu, 2016; Wu et al., 2015). This, in turn, would lead to higher levels of performance in work-related tasks (Vogelsang, 2018). Given the importance of work in the lives of individuals, work environments also play an important role in identity development and personality formation (Wu, 2016). As such, task performance is a function of grit, and that grit is a function of the fit between the individual and the nature of the task. Similarly, performance is also related to person-environment fit (Hoffman & Woehr, 2006). There is thus theoretical support (as discussed in the previous sections) and some empirical evidence to suggest that grit may act as a potential mediator between person-environment fit and task performance.

These assumptions are supported by the Person-Environment Fit Theory (Edwards et al., 1998) and the theory of work adjustment (Dawis, 2005). These theories postulate that person-environment fit acts as an indicator of an inherent alignment in what people are passionate about, what they are competent at, what they enjoy doing (i.e. consistency of interest) and the nature of their work. This interest does not just stem out of curiosity, but rather through the deep congruence of values between themselves, their passions and their environment (person-environment fit), the impression that they can contribute to something they value (demands-ability fit) and receive benefits in case they perform well (needs-supply fit) (Van der Vaart et al., 2021). This deep congruence between personal interests, -values and the nature of the work environment ensure a deeper, personal connection to organization goals, whereby individuals are more likely to invest effort in achieving such despite being faced with difficulties or challenges (i.e. perseverance) (Armitage & Amar, 2021; Edwards et al., 1998). Both components of grit seem, at least theoretically, to be key outcomes of a good person-environment “fit”.

-

Hypothesis 2: Grit indirectly affects the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance.

Finally, grit could also be classified as a potential moderating factor that explains how different person-environment fit levels can explain performance. Individuals whose personal characteristics, needs, and abilities match these job requirements and have a deep-seated interest and desire to perform these job-related tasks are more likely to perform better than their peers who report lower levels of grit (Duckworth et al., 2007). This person-environment fit-performance relationship is thus strengthened when the core requirements or nature of the work/goal/interest align with an individual’s signature strengths, work preferences, or personality (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Vleugels & De Cooman, 2016). The negative impact of a poor person-environment fit on performance can therefore be offset by activating one’s personal resources as a means to facilitate more flexibility (as noted in the previous section). We, therefore, postulate that high levels of grit may offset the negative impact that a poor person-environment fit has on performance and strengthen the relationship if a good fit is reported.

-

Hypothesis 3: Grit moderates the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance.

The current study

As such, grit seems to be an interesting mechanism for exploring the role of personal resources in the motivational process of the JDR model. Conceptually, grit could act as a direct antecedent-, mediator and moderator within the person-environment fit and task performance relationship. Therefore, this paper aims to explore the function of grit (as a personal resource) within the person-environment fit (job resource) and task performance relationship. Specifically, the aim is to determine if grit directly or indirectly affects the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. Finally, it aims to investigate whether grit moderates this relationship.

This study extends the existing literature on the role of trait-like personal resources in the motivational process of the JDR model. It highlights the theoretical ambiguity around the function of trait-like personal resources like grit within the person-environment fit and task performance relationship. Further, it provides empirical support for the theoretical assumptions that person-environment fit could lead to changes in trait-like characteristics and their relationship to performance. The study thus highlights the importance of creating a positive environment that “fits” the individual’s needs, demands, strengths and capabilities as a means to create high-performing, gritty employees.

Methods

Research design

A cross-sectional, online survey-based research design was employed to investigate the relationship between person-environment fit, grit and task performance. This design allows for data to be drawn from a single timestamp to evaluate the extent of the relationships given the current contextual conditions (Van Zyl, 2013).

Participants

A convenience sampling strategy was employed to draw 310 respondents to participate in this research. Table 1 provides a descriptive overview of the demographic characteristics of the participants. The majority of the participants were single (45%) German-speaking (62.7%), German (64.0%) females (69.1%) between the ages of 21 and 30 years (43.1%). Most of which held at least a high school diploma (28.9%) and worked between 0 and 5 years (76.8%) in their current position.

Measures

Several self-report instruments were used to assess the focal factors and control variables in the study:

Focal Factors

The Person-Environment Fit Scale (PEFS) developed by Cable and DeRue (2002) was used to measure person-environment fit and its three underlying constructs: Person-Organization Fit, Need-Supply Fit and Demand-Ability Fit. The instrument consisted out of 9 items rated on a seven-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (‘Strongly Disagree’) to 7 (‘Strongly Agree’). Person-organization fit was measured by three items (e.g. ‘The things that I value in life are very similar to the things that my organization values.’) as was Need-Supply fit (‘The attributes that I look for in a job are fulfilled very well by my present job.’) and Demand-Ability Fit (‘My personal abilities and education provide a good match with the demands that my job places on me.’). Acceptable levels of internal consistency of the instrument have been reported with Cronbach Alphas ranging from 0.91 (Person-Organization Fit) and 0.93 (Need-Supply Fit) to 0.89 (Demand–Supply Fit) (Cable & DeRue, 2002).

The Grit-O Scale developed by Duckworth et al. (2007) was used to measure grit. The 12-item questionnaire measuring the two components, consistency of interest (6 items: e.g. ‘My interests change from year to year’) and perseverance (6 items: e.g. ‘I have overcome setbacks to conquer an important challenge’), was rated on a five-point Likert-scale ranging from 1 (‘Not like me at all’) to 5 (‘Very much like me’). The Grit-O scale has shown acceptable levels of internal consistency with Cronbach Alphas of 0.84 on both scales (Duckworth et al., 2007).

The Task Performance Sub-scale of the Individual Work Performance Scale developed by Koopmans et al. (2012) was employed to measure task performance. Task performance was measured by seven items on a six-point Likert-Scale ranging from 1 (‘Never’) to 6 (‘Always’). An example of an item is: ‘I kept in mind the results that I had to achieve in my work’. Magada and Govender (2017) found acceptable levels of internal consistency for the instrument with a Cronbach Alpha level of 0.86.

Control Variables

A biographical questionnaire was used to gather biographic information about the participants relating to their gender, age, home language, nationality, marital status, level of education and years of employment in their current role. Self-reported biological gender and age categories were used as control variables.

Statistical analysis

Data were processed by using JASP v. 0.14.1 (JASP, 2021), SPSS v. 27 (IBM, 2021) and Mplus v 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, 2021). A step-wise sequential analytical strategy, through Structural Equation Modelling (SEM), was used to test the hypotheses of the study. Missing data was managed through the full maximum likelihood estimation method (FIML), the default approach in Mplus.

First, common method bias was tested by estimating both Harman’s (1976) single factor test and the common latent factor approach (Podsakoff et al., 2003; Tehseen et al., 2017). For Harman’s single factor test, all observed indicators were entered into an unrotated exploratory factor analysis. Here, it was specified that a single component, via principal component analyses, should be extracted from the data. The extracted variance should not exceed 50% (Fuller et al., 2016). Thereafter, a confirmatory factor analytical approach was employed to determine if a single latent factor could be extracted from the data. All observed indicators or specified to load onto a unidimensional first-order factor within the SEM framework. This unidimensional model should not produce an adequate level of data-model fit, and the unstandardized variance should be low (Tehseen et al., 2017). Finally, Podsakoff and colleagues’ (2003) common latent factor approach was employed. Within an a priori measurement model, an additional single latent factor was estimated where all observed indicators were estimated to load onto such directly. The variance of the common latent factor was constrained to 1, and the factor loadings were constrained to be equal. This model is then compared, based on χ2, to a model where there is no common latent factor specified. These models should be statistically equivalent. Common method bias is not a concern if all these conditions are met.

Second, descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis), Pearson correlations, and McDonald’s Omega / Cronbach Alphas were calculated to test for multivariate normality, determine the relationships between the factors, and estimate the reliability of the various instruments. Data were considered normally distributed if the Skewness and Kurtosis did not exceed the + 2 / -2 range (Kim, 2013). Further, statistical significance for the Pearson correlation coefficients was set at 95% (p ≤ 0.05), whereas the practical significance or ‘effect sizes’ was set at 0.30 (medium effect) and 0.50 (large effect) (Ferguson, 2009). The reliability of the instruments was estimated through both Cronbach Alpha (> 0.70; Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994) and McDonald’s Omega (> 0.70; Wang & Wang, 2020) to interpret scale reliability.

Third, a competing measurement modelling strategy with the maximum likelihood estimation (ML) method in SEM was employed to determine the best-fitting model for the data. A series of theoretically informed competing measurement models were then estimated and sequentially compared based on: (a) traditional data-model fit criteria (c.f. Table 2; Van Zyl and Ten Klooster, 2022), and (b) measurement quality (McNeishet al., 2018). Measurement quality was assessed through inspecting the various parameter estimates of the models (standardized factor loadings λ > 0.40; item uniqueness > 0.1 but < 0.9; no multiple cross-loadings) (Van Zyl and Ten Klooster, 2022). Models needed to show both acceptable levels of data-model fit and measurement quality to be retained for further analysis.Footnote 1

Fourth, structural models were then estimated based on the best-fitting measurement model (Muthén & Muthén, 2021). These structural models were used to estimate the direct, linear relationship between latent factors. Here model-fit and measurement quality were also inspected, but the significance of the direct relationships between the factors (p < 0.05) and the variance explained in endogenous factors were of direct concern.

Fifth, to estimate the indirect effect of grit on the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance, a path model with the bias-corrected bootstrapping (BCB; Preacher et al., 2010) was used. A 50 000 BCB was set to impute the indirect effect estimate and the confidence range at the 95% confidence interval limit. To establish mediation, the standardized indirect effect estimate should be significant (p < 0.05), and the confidence interval range should not include zero (Wong & Wong, 2020).

Finally, a moderation model with the direct effect of person-environment fit on task performance being moderated by grit was estimated using Hayes’s (2020) PROCESS v.4 macro in SPSS v. 27 (IBM, 2021). Factor scores for the best fitting measurement model were saved and used for the moderation estimation, and therefore, neither grit nor person-environment fit was centred (DiStefano et al., 2009; Ng & Chan, 2020). A step-wise hierarchical regression approach was adopted whereby the factor scores of person-environment fit (independent variable) were entered in the first step, followed by the factor scores of grit (moderator) and age/gender as covariates in the second step. In the final step, an interaction term based on the product of person-environment fit x grit was entered to test for possible moderation. There is evidence of moderation when the interaction term is significantly related to the dependent variable (p < 0.05) and if the confidence interval range does not include zero (Hayes, 2020).

Results

Common Method Bias

A series of increasingly restrictive statistical approaches were implemented to assess the presence of CMB. First, Harman’s single factor test was estimated through an unrotated exploratory factor analysis. The results showed that a single factor could be extracted from the data and that the shared common variance (27.36%) was below 50% (Fuller et al., 2016). Second, the single latent factor approach suggested by Podsakoff et al. (2003) was used. All measured or ‘observed’ indicators were specified to load onto a single latent factor. The results showed that a single factor fitted the data poorly (χ2(310) = 2313.89; df = 350; CFI = 0.50; TLI = 0.46; RMSEA = 0.13 [0.129—0.140] p < 0.01; SRMR = 0.14). Further, the unstandardized variance of this single-factor model was 7.2%. Finally, the common latent factor approach was estimated. The result showed that the variance explained by the common latent factor is low (< 50%) and that no significant difference in χ2 is apparent (p > 0.05). Therefore, common method bias may not be an issue in the current model, and we can proceed to the next step.

Descriptive statistics, reliabilities and correlations

Table 3 provides an overview of the descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, skewness, kurtosis), reliability estimates, and the Pearson correlation coefficients of person-organization fit, grit, and task performance. The results showed that the data was relatively normally distributed (Skewness and Kurtosis ranging between + 2 and -2) and that all instruments showed to be reliable at both the lower- (Cronbach Alpha > 0.70) and upper bound limits (McDonald’s ω > 0.70). Further, on scale level, person-environment fit correlated statistically significantly with both grit (r = 0.30; p < 0.05; medium effect) and task performance (r = 0.31; p < 0.05; medium effect). Similarly, grit correlated statistically significantly with task performance (r = 0.45; p < 0.05). With the exclusion of the non-significant relationship between consistency of effort and demand-ability fit, all other factors correlated significantly and positively.

Comparing competing measurement models

A competing measurement model was employed to determine the best fitting model for the data. Various theoretically informed factorial models were estimated and systematically compared to determine the best fitting model. Observed indicators (items) were treated as indicators for first-order latent variables. All items were estimated to load directly onto their a priori factorial models, and no items were removed. To control for age and gender, these factors were permitted to freely covary with all latent factors in each estimated measurement model. As such, the following four confirmatory factor analytical models were estimated and compared (c.f. Appendix A for a graphical representation):

-

Model 0: First-order factorial (or ‘unidimensional’) models were specified for person-environment fit, grit and task performance.

-

Model 1: A second-order factorial model for both person-environment fit, comprised of three first-order factors (person-organization fit, need-supply fit, and demand-ability fit), and grit, comprised of two first-order factors (consistency of interest and perseverance of effort) were estimated. A single, first-order factor for task performance was estimated. In the second iteration of this model, the residual variance for Item 1 (‘I managed to plan my work so that it was done on time’) and Item 2 (‘My planning was optimal’) of the Task Performance scale were correlated to improve fit.

-

Model 2: A second-order factorial model for person-environment fit, comprised of three first-order factors (person-organization fit, need-supply fit, and demand-ability fit) was estimated. Both grit and task performance were estimated as unidimensional first-order factors.

-

Model 3: A three first-order factor model for person-environment fit was fitted to the data, where three items loaded on person-organization fit, three items on need-supply fit and three items on demand-ability fit. Further, a second-order factorial model for grit was estimated, where grit was the function of two first-order factors (consistency of interest and perseverance of effort). Task performance was specified as a unidimensional first-order factor.

-

Model 4: A three first-order factor model for person-environment fit was fitted to the data, where three items loaded on person-organization fit, three items on need-supply fit and three items on demand-ability fit. Further, a two first-order factorial model for grit was estimated where six items loaded on the consistency of interest and six items on the perseverance of effort. Task performance was specified as a unidimensional first-order factor.

-

Model 5: A three first-order factor model for person-environment fit was fitted to the data, where three items loaded on person-organization fit, three items on need-supply fit and three items on demand-ability fit. Further, a second-order factorial model for grit was estimated, where grit was the function of two first-order factors (consistency of interest and perseverance of effort). Task performance was specified as a unidimensional first-order factor.

The goodness-of-fit indices for all four models are summarised in Table 4. When controlling for age and gender, the results showed that the original hypothesized model, where Person-Environment Fit (comprised of person-organization fit, demand-ability fit and need supply fit) and Grit (comprised of consistency of interest and perseverance of effort) are estimated as second-order factorial models and Task Performance as a single first-order factor, fitted the data the best (Model 1: χ2(310) = 761.57; df = 392; CFI = 0.91; TLI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.06 [0.049—0.061] p > 0.05; SRMR = 0.07). Model 1 also showed a comparatively better fit than all other estimated models with lower χ2, RMSEA, SRMR, AIC and BIC values and higher CFI and TLI estimates. Further, looking at measurement quality, Model 1 was the only model where all indicators of measurement quality were met (λ > 0.40; item uniqueness > 0.1 but < 0.9). Therefore, Model 1 was retained for further analysis..

Estimating competing structural models

Two structural path models were estimated based on the best fitting measurement model. Structural Model 1 was specified as a “process model” where person-environment fit was positioned as the input (exogenous) factor, grit the process factor (mediator), and task performance the outcome (endogenous) factor. Structural Model 2 was specified as an “antecedents” model where both grit (future moderator) and person-environment fit were positioned as endogenous factors that directly related to task performance (endogenous factor). In both structural models, we controlled for age and gender. The model fit statistics for both models are summarised in Table 5.

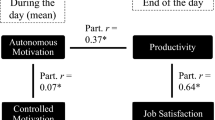

The first structural model (c.f. Figure 1) fitted the data adequately (Model 1: χ2 (391, N =310) = 752.30; TLI = 0.91; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.06 [0.049-0.060] p > 0.05; SRMR = 0.07; AIC = 24,676.72; BIC = 25,065.66; aBIC = 24,735.81). The results showed that person-environment fit was positively associated with Grit (β = 0.39; S.E = 0.07; p < 0.05) and explained 27% of its variance. Similarly, Grit was positively associated with Task performance (β = 0.71; S.E = 0.12; p < 0.05) and explained 49% of its variance.

When looking at the control variables, age was significantly associated with Person-Environment Fit (Cov = 0.33; S.E. = 0.07; p < 0.05), where Gender wasn’t (Cov = -0.03; S.E. = 0.02; p > 0.05). Further, Age (β = 0.23; S.E = 0.07; p < 0.05) and Gender (β = 0.13; S.E = 0.07; p < 0.05) as significantly related to Grit. However, neither Age (β = -0.10; S.E = 0.08; p > 0.05) nor Gender (β = -0.08; S.E = 0.06; p > 0.05) was associated with Task Performance. Structural Model 1 was therefore retained for indirect effects estimation.

The second structural model (c.f. Figure 2) only partially fitted the data (Model 2: χ2 (390, N =310) = 766.61; TLI = 0.91; CFI = 0.90; RMSEA = 0.06 [0.050-0.062] p > 0.05; SRMR = 0.10; AIC = 24,693.04; BIC = 25,085.72; aBIC = 24,752.70). In this model, two additional error terms on the Task Performance scale (Item 5 with Item 4 and Item 7 with 6) were permitted to covary in order to enhance the overall model fit. Despite these modifications, SRMR still did not meet the suggested threshold (SRMR < 0.08). However, SRMR is sensitive to small samples (Van Zyl and Ten Klooster, 2022) and given that all other criteria are met, a case can be made to retain the model for further analysis.

The results showed that both person-environment fit (β = 0.17; S.E = 0.08; p < 0.05) and Grit (β = 0.71; S.E = 0.09; p < 0.05) were directly and positively associates with task performance and explained 54% of its variance. When considering the control variables, only age significantly covaried with Person-Environment Fit (Cov = 0.26; S.E. = 0.06; p < 0.05) and Grit (Cov = 0.06; S.E. = 0.02; p < 0.05). Gender was not statistically significantly related to either person-environment fit nor grit. Further, neither age (β = -0.13; S.E = 0.08; p > 0.05), nor gender (β = -0.08; S.E = 0.07; p > 0.05) affected task performance. Structural Model 2 was therefore retained for moderation estimation.

Bullet Hypothesis 1 can therefore be accepted.

Indirect effect estimation: grit as a mediator

Structural Model 1 was used to determine whether grit indirectly affects the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. While controlling for age and gender, the results indicate that a significant indirect effect exists between person-environment fit, and task performance via grit at the 95% CI range (lower = 0.15 to upper = 0.63). As the indirect effect estimate was significant (0.28; SE: 0.13; p < 0.01) and the bias-corrected CI range did not include zero, it could be said that grit indirectly affects the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance.

Therefore, Hypothesis 2 can be accepted.

Interaction effect estimation: grit as a moderator

Structural Model 2 was used to determine whether grit could moderate the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. The hierarchical regression procedure of Hayes (2021) was employed with the factor scores of the best fitting measurement model.

The results, summarised in Table 6 and presented in Fig. 3, indicate that variables accounted for a significant amount of variance in task performance (F(5, 302) = 79.56; p < 0.05; R2 = 56.84%). However, when the interaction term (person-environment fit x grit) was added to the model, the results showed that such did not account for any additional statistically significant variance in the task performance (F(1, 302) = 3.13; β = -0.31; S.E = 0.18; p = 0.08; t = -1.77; ΔR2 = 0.05%). Further, the CI range of the interaction term includes zero (LCI = -0.66; UCI = 0.04). Taken together, the results show that grit does not significantly affect the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance.

Therefore, Hypothesis 3 was not accepted.

Discussion

The Job Demands-Resources Framework (JDR) has established job- and personal resources as essential elements motivating people to perform. Whilst the purpose of job resources in this motivational process is well established, the role of personal resources is still quite ambiguous. As such, this paper aimed to explore the function of grit (as a personal resource) within the person-environment fit (as a job resource) and task performance relationship. Primarily, it aimed to determine if grit was a direct antecedent of task performance or if it mediated or moderated the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. When controlling for age and gender, the results showed positive direct associations between person-environment fit, grit and task performance within the current sample. Further, grit was found to indirectly affect the relationship between the person-environment fit and task performance. However, the results also show that grit does not moderate the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. This signifies the importance of grit as a psychological process rather than a buffering element which may explain how person-environment fit leads to performance outcomes.

Direct relationships between person-environment fit, grit and task performance

Whilst controlling for age and gender, our first finding that person-environment fit and grit are directly and positively related to task performance corroborates previous research (Vogelsang, 2018). Two competing structural models were constructed and compared to explore the direct relationships between the factors: a process model (where person-environment fit was regressed on grit and grit on task performance) and an antecedent model (where person-environment fit and grit were directly related to task performance). Although both models fitted the data, the result showed more support for the process model.

The process model supports the notion that when an individual’s needs, abilities, values, and capabilities match or ‘fit’ the requirements/demands of work, employees are more likely to show sustained effort and perseverance in achieving their long-term goals (i.e. show more grit). Further, gritty individuals are also more likely to perform better in executing their work-related tasks. When there is a good person-environment fit, individuals can more readily live out their strengths at work, which helps increase performance (Dawis, 2005). This is in line with previous research (c.f. Vogelsang, 2018), the theory of work adjudgment (Dawis, 2005) and the theory of Psychological Strengths (Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Vogelsang (2018) also found that person-environment fit directly relates to grit, which in turn explained variance in task performance.

Additionally, our results also support propositions within the theory of work adjustment by showing that environmental factors are associated with personal characteristics. The direct relationship between person-environment fit and grit could also be explained through the perseverance component of the adjustment principle. When individuals perceive a lack of fit between their characteristics and their environments, it activates their ability to try and adjust work or push through difficult situations without giving up (Dawis, 2005). The conceptual overlap between perseverance as an adjustment function and perseverance within the grit conceptualization may explain why person-environment fit is associated with grit. From the psychological strengths perspective, Peterson and Seligman (2004) argued that when there is a match between the characteristics of the individual and their environment, they are more likely and able to use their strengths at work. When one’s strengths are lived out in work, it fosters a deeper interest in work-related goals/tasks and shows more perseverance in achieving long-term individual and organizational goals. This, in turn, yields more positive individual- and performance outcomes.

Similarly, the antecedents model also showed direct positive relationships between person-environment fit, grit and performance. Here, the relationship between the job- and personal resources was not specified, but rather positioned as directly affecting task performance. In this model, grit had a stronger association with task performance than person-environment fit. This was in line with previous research. In a meta-analysis, Kristof-Brown et al. (2005) found that the person-organization- and need-supply fit components were slight to moderately related to objective and subjective performance measures. This is in contrast to other findings such as those of Greguras and Diefendorff (2009), Lauver and Kristof-Brown (2001) and Redelinghuys et al. (2019), who reported moderate to strong relationships between person-environment fit and various forms of performance. Within the current context, the congruence between the characteristics of the individual and the demands of the environment, therefore, seems to play a lesser role in explaining task performance.

Given that work is fundamentally goal-directed and that performance is measured against the successful completion of work-related tasks (Armitage & Amar, 2021), it is not surprising that grit was positively associated with task performance in this study. Our findings show that when individuals report a capacity to sustain long-term effort and interest in their goal pursuits, they may also report higher performance levels in completing their work-related tasks. In line with Duckworth’s (2016) grit theory, performance is more than just a function of employees’ cognitive abilities and competencies, but rather the outcome of the passion showed in- and enduring effort expressed when pursuing (work-related) goals. Our findings, substantiated by Eskreis-Winkler et al. (2014), indicate that gritty employees may work more diligently to achieve their work-related tasks as they may be better equipped to utilize their capabilities and skills at work. These employees may also be less affected by failures/setbacks and less likely to be distracted by only pursuing short-term goals (c.f. Credé et al., 2017; Eskreis-Winkler et al., 2014; Von Culin, et al., 2014). Taken together, the antecedent model showed that grit played a more significant role in facilitating performance than person-environment fit.

Grit as a personal resource: The mediating mechanism

The study supported the mediating role that grit could play in the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. This implies that when individuals perceive a fit between themselves and their work environment, they are more likely to show sustained effort and perseverance in achieving their long-term goals, which may affect work-related performance. Given that individuals spend more than a third of their lives at work or engaged in work-related activities, Van Zyl et al. (2010) argued that work becomes central to the identity of individuals. This implies that if there is a congruence between the individual and his/her (work) environment (person-environment fit), work goals could be seen as personal goals- and vice versa (Armitage & Amar, 2021). Employees might then feel that they not only contribute to something they value but also something larger than themselves. Therefore, they may work hard and diligently and persist in achieving these goals. Thus, when gritty individuals fit in with their environment, they may show long-term interest in the organization’s goals and be more motivated to push through obstacles and setbacks to achieve these, resulting in higher levels of performance (Suzuki et al., 2015). As such, our results support the notion that grit can be considered an essential explanatory mechanism explaining how perceptions of person-environment fit may translate into task performance at work.

Grit as a personal resource: The (lacking) moderating effect

Finally, the study aimed to explore the potential moderating effect of grit on the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. Our results did not show any evidence for the proposition that higher levels of grit buffer against the negative impact a poor person-environment fit has on task performance. Nor did we find support that grit may strengthen the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. Individuals whose personal characteristics, needs, and abilities match these job requirements and have a deep-seated interest and desire to perform these job-related tasks are no more likely to perform better at work-related tasks than those who report lower levels of grit (Duckworth et al., 2007). The negative impact of a poor person-environment fit on performance can therefore not be offset by activating one’s grit.

Implications, limitations and recommendations

Although the relationship between person-environment fit and performance has enjoyed much scientific attention during the last three decades, its explanatory mechanisms have been studied to a lesser extent (Armitage & Amar, 2021; Gregory et al., 2010). From a JDR perspective, our study explored the three different roles personal resources (such as grit) could play in explaining the relationship between the factors. First, person-environment fit and grit was found to directly relate to task performance. In this antecedents model, grit showed to have the strongest direct relationship with task performance. However, this model showed poor fit and required additional modifications to meet minimum model fit and measurement quality criteria. Second, this study proposed and found support for grit as a mechanism which indirectly affects the person-environment fit and task performance relationship. Finally, and in contrast to our initial expectations, grit was found not to moderate the relationship between the variables. This implies that grit could be seen as an important psychological process that translates person-environment fit into task performance, but not as a mechanism which buffers against the effects poor person-environment fit has on task performance. The findings further the debate on the role and nature of personal resources within the JDR framework.

Further, this study expands the nature and use of grit into organizational contexts; where previous studies have focused mainly on grit within educational- or sports environments (c.f. Datu, 2021). The mediating effect of grit in the current study indicates ways in which grit can be relevant in connection to even the most basic work attitudes. The current project can be seen as the first to measure the link between person-environment fit and grit and between grit and specific workplace performance metrics. Given the exploratory nature of this study, no solid conclusions can be drawn about the exact role and function grit plays within organizational contexts. However, our results do open up the way for more conceptual and empirical research on the importance of grit and personal resources in facilitating performance-related outcomes within organizations.

From a practical perspective, our results highlight the importance of creating a positive organizational climate that facilitates the alignment between the person- and the work requirements. Two directions to improve this alignment are presented. First, during the recruitment process, managers should assess for person-job fit to ensure a direct alignment between the person’s work preferences, abilities, skills, values and personality and the nature of both the function and the organizational culture. Assessing people’s core values and matching them with the job demands and organizational culture during the selection process could avoid dissolution on the employees’ side and prevent the costliness of a wrong appointment for the organization. Second, managers should attempt to match employees’ work-related tasks to their preferences to enhance their performance. Literature on the (re)crafting of work shows that this is not only the responsibility of managers but that employees can be proactive crafters of their work environment (Chen et al., 2022; Tims et al., 2016; Wrzesniewski & Dutton, 2001). The structural changes made to job demands and resources may turn out to have consequences for grit too. This reiterates the need for a collective responsibility to create a positive organizational climate where people experience psychological safety. Grit is a result of a two-way interaction between leaders and employees. Employees will be comfortable sharing a poor fit with their work environment or clarifying expectations to improve their fit with their tasks and the work environment. Healthy relationships between employees and leaders will form the cornerstone of a positive climate that’s conducive to building grit and performance. Experiencing a positive organizational environment will strengthen employees’ willingness to work hard, enable them to cope with challenges and help them manage obstacles in the long term.

The results of the study are also subjected to several limitations. First, all factors are measured with subjective, self-report measures, which may not accurately represent experiences of person-environment fit, grit or task performance. Subjective self-report measures are sensitive to both social desirability and confirmation bias. Future research should attempt to employ more objective measures for the factors such as raw performance scores, supervisor grit ratings or employ more ecological perspectives to assess person-environment fit. Second, only task performance was assessed. Task performance only represents the efficiency with which individuals complete core aspects of their job and doesn’t provide a holistic view of overall performance. Future research should employ more objective task performance measures or more multi-dimensional approaches to performance. Further, the participants' socio-economic status may also have impacted their perceptions of perceived person-environment fit and grit. Those with a higher income level and thus a higher socio-economic status may perceive work more positively as opposed to those receiving a lower salary. Future research should consider these factors and actively control for their potential impact. Finally, the results showed that age and gender may have had an impact on the results of the study. Future research should investigate the specific age and gender effects in the relationship and explore how and why these factors influenced grit and person-environment fit.

We also urge future research to address the current scepticisms raised against grit. This will include better theorizing, measurement, and methodological approaches towards understanding grit (Datu, 2021; Tynan, 2021; Van Zyl & Rothmann, 2022) and determining the various antecedents/outcomes of grit in various contexts. Furthermore, research on interventions to develop grit is needed (Van Der Vaart et al., 2021) and the possible aversive effects such should be explored (Jordan et al., 2019).

Conclusion

This study provides the first empirical inquiry into the differential roles that personal resources such as grit can play in the relationship between person-environment fit and task performance. The results showed that if a match between an individual’s perceived self (strengths, abilities, personality etc.) and the culture, needs and demands of the organization exists, these individuals are more likely to show higher levels of grit (consistency of interest and perseverance) at work which in turn may affect their task-related performance. The results indicate mediating rather than moderating effects of grit, putting grit at the centre of the experiences of working life and its success.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Notes

Age and gender were controlled for in both the measurement- and structural models as well as during the mediation and moderation estimations. Within the measurement models age/gender were permitted to feely covary with all latent factors. For the structural- and mediation models, age/gender was permitted to freely covary with exogenous- and regressed on endogenous factors (Kline, 2010). Finally, age/gender were added as covariates for the moderation estimation (Hayes, 2018).

References

Armitage, L. A., & Amar, J. H. N. (2021). Person-Environment Fit Theory: Application to the design of work environments. In R. Appel-Meulenbroek & D. Vitalija (Eds.), A Handbook of Theories on Designing Alignment Between People and the Office Environment (pp. 14–26). Routledge.

Arthur, W., Jr., Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., & Doverspike, D. (2006). The use of person-organization fit in employment decision making: An assessment of its criterion-related validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(4), 786.

Ayoko, O. B., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (Eds.). (2019). Organizational behaviour and the physical environment. Routledge.

Azari Noughabi, M., Ghonsooly, B., & Jahedizadeh, S. (2022). Modeling the associations between EFL teachers’ immunity, L2 grit, and work engagement. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 1–16

Bakker, A. B., & de Vries, J. D. (2021). Job Demands-Resources theory and self-regulation: New explanations and remedies for job burnout. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 34(1), 1–21.

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2017). Job demands–resources theory: Taking stock and looking forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273.

Bolger, N., & Zuckerman, A. (1995). A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69(5), 890.

Cable, D., & DeRue, D. S. (2002). The Convergent and Discriminant Validity of Subjective Fit Perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87(5), 875–884. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.87.5.875

Chen, S., van der Meij, L., Van Zyl, L. E., & Demerouti, E. (2022). The Life Crafting Scale: Development and Validation of a Multi-Dimensional Meaning-Making Measure. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 795686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.795686

Chi, N. W., Fang, L. C., Shen, C. T., & Fan, H. L. (2020). Detrimental effects of newcomer person-job misfit on actual turnover and performance: The buffering role of multidimensional person-environment fit. Applied Psychology, 69(4), 1361–1395.

Credé, M. (2018). What shall we do about grit? A critical review of what we know and what we don’t know. Educational Researcher, 47(9), 606–611.

Credé, M., Tynan, M. C., & Harms, P. D. (2017). Much ado about grit: A meta-Analytic synthesis of the grit literature. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(3), 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000102

Creschi, A., Sartori, R., Dickert, S., & Constantini, A. (2016). Grit or honesty-humility? New steps into the moderating role of personality between the health impairment process and counterproductive work behaviour. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1799. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01799

Datu, J. A. D. (2021). Beyond Passion and Perseverance: Review and Future Research Initiatives on the Science of Grit. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 545526.

Dawis, R. V. (2005). The Minnesota Theory of Work Adjustment. In S. D. Brown & R. W. Lent (Eds.), Career development and counseling: Putting theory and research to work (pp. 3–23). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Demerouti, E., Bakker, A. B., Nachreiner, F., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2001). The job demands-resources model of burnout. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(3), 499.

DiStefano, C., Zhu, M., & Mindrila, D. (2009). Understanding and using factor scores: Considerations for the applied researcher. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 14(1), 20.

Duckworth, A. (2016). Grit: The power of passion and perseverance. Scribner Publishers.

Duckworth, A. L., Peterson, C., Matthews, M. D., & Kelly, D. R. (2007). Grit: Perseverance and passion for long-term goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(6), 1087–1101. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1087

Duckworth, A. L., & Quinn, P. D. (2009). Development and validation of the Short Grit Scale (Grit-S). Journal of Personality Assessment, 91(2), 166–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223890802634290

Edwards, J. R., Caplan, R. D., & Van Harrison, R. (1998). Person-environment fit theory. Theories of Organizational Stress, 28(1), 67–94.

Edwards, J. R., & Shipp, A. J. (2007). The relationship between person-environment fit and outcomes: An integrative theoretical framework. In C. Ostroff & T. A. Judge (Eds.), Perspectives on organizational fit (pp. 209–258). Jossey-Bass.

Eskreis-Winkler, L., Shulman, E. P., Beal, S. A., & Duckworth, A. L. (2014). The grit effect: Predicting retention in the military, the workplace, school and marriage. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(36), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00036

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: A guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 532–538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808

Frese, M. (1982). Occupational socialization and psychological development: An underemphasized research perspective in industrial psychology. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 55(3), 209–224.

Fuller, C. M., Simmering, M. J., Atinc, G., Atinc, Y., & Babin, B. J. (2016). Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3192–3198.

Gregory, B. T., Albritton, M. D., & Osmonbekov, T. (2010). The mediating role of psychological empowerment on the relationship between P-O fit, job satisfaction, and In-role performance. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 639–647.

Greguras, G. J., & Diefendorff, J. M. (2009). Different fits satisfy different needs: Linking person-environment fit to employee commitment and performance using self-determination theory. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(2), 465–477.

Harman, H. H. (1976). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago press.

Hayes, A. F. (2020). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Publications.

Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127.

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.3.513

Hoffman, B. J., & Woehr, D. J. (2006). A quantitative review of the relationship between person–organization fit and behavioral outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 389–399.

Hunter, J. E. (1983). A causal analysis of cognitive ability, job knowledge, job performance, and supervisory ratings. In F. Landy, S. Zedeck, & J. Cleveland (Eds.), Performance measurement and theory (pp. 257–266). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

IBM. (2021). IBM SPSS statistics for Windows version 26. IBM Corp.

Jachimowicz, J. M., Wihler, A., Bailey, E. R., & Galinsky, A. D. (2018). Why grit requires perseverance and passion to positively predict performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(40), 9980–9985.

JASP. (2021). Jeffery’s Amazing Stats Program (v.0.14.1). Accessed via the World Wide Web: https://jasp-stats.org

Jordan, S. L., Ferris, G. R., Hochwarter, W. A., & Wright, T. A. (2019). Toward a work motivation conceptualization of grit in organizations. Group & Organization Management, 44(2), 320–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601119834093

Jumat, M. R., Chow, P. K., Allen, J. C., Jr., Lai, S. H., Hwang, N. C., Iqbal, J., Mok, M., Rapisarda, A., Velkey, J. M., Engle, D. L., & Compton, S. (2020). Grit protects medical students from burnout: a longitudinal study. BMC Medical Education., 20(1), 266.

Karasek Jr, R. A. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 285–308.

Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54.

Kim, Y. J., & Lee, C. S. (2015). Effects of Grit on the successful aging of the elderly in Korea. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 57(8), 373–378. https://doi.org/10.17485/ijst/2015/v8iS7/70421

Kline, R. B. (2010). Principles and practices of structural equation modelling (3rd ed.). Gilford Press.

Kodden, B., & Hupkes, L. (2019). Organizational environment, personal resources and work engagement as predictors of coaching performance. Journal of Management Policy and Practice, 20(3), 53–71.

Kok, J., & Van Den Heuvel, S. C. (2019). Leading in a VUCA world: Integrating leadership, discernment and spirituality. Springer Nature.

Koopmans, L., Bernaards, C. M., Hildebrandt, V. H., Van Buuren, S., Van der Beek, A. J., & De Vet, H. C. W. (2012). Development of an individual work performance questionnaire. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 62(1), 6–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/17410401311285273

Kristof-Brown, A., & Guay, R. P. (2011). Person-environment fit. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (pp. 1–50). American Psychological Association.

Kristof-Brown, A., Zimmerman, R. D., & Johnson, E. C. (2005). Consequences of individuals’ fit at work: A meta-analysis of person-job, person-organization, person-group, and person-supervisor fit. Personnel Psychology, 58(1), 281–342.

Lauver, K. J., & Kristof-Brown, A. (2001). Distinguishing between employees’ perceptions of person-job and person-organization fit. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 59, 454–470. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1807

Li, J., Fang, M., Wang, W., Sun, G., & Cheng, Z. (2018). The influence of grit on life satisfaction: Self-esteem as a mediator. Psychologica Belgica, 58(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.5334/pb.400

Li, W. D., Fay, D., Frese, M., Harms, P. D., & Gao, X. Y. (2014). Reciprocal relationship between proactive personality and work characteristics: a latent change score approach. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(5), 948.

Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60(3), 541–572.

Magada, T., & Govender, K. K. (2017). Culture, leadership and individual performance: A South African Public Service Organization study. Journal of Economics and Management Theory, 1(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.22496/jemt20161104109

Mazzetti, G., Robledo, E., Vignoli, M., Topa, G., Guglielmi, D., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2021). Work Engagement: A meta-Analysis Using the Job Demands-Resources Model. Psychological Reports, 00332941211051988.

McNeish, D., An, J., & Hancock, G. R. (2018). The thorny relation between measurement quality and fit index cut-offs in latent variable models. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100(1), 43–52.

Mishra, A. K., Vinzé, A. S., Gupta, R. S., & Menon, R. (Eds.). (2021). Advances in innovation, trade and business: evidence from emerging economies. Springer Nature.

Muthén, L. K., and Muthén, B. O. (2021). Mplus (Version 8.4). [Statistical software]. Muthén and Muthén.

Ng, J. C., & Chan, W. (2020). Latent moderation analysis: A factor score approach. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 27(4), 629–648.

Nunnally, J. C., & Bernstein, I. H. (1994). Psychometric theory (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

O’Reilly, C. A., Chatman, J., & Caldwell, D. F. (1991). People and organizational culture: A profile comparison approach to assessing person-organization fit. Academy of Management Journal, 34, 487–516.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Peterson, S. J., Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Walumbwa, F. O., & Zhang, Z. (2011). Psychological capital and employee performance: A latent growth modeling approach. Personnel Psychology, 64(2), 427–450.