Abstract

Background

Patient satisfaction measures have important implications for physicians. Patient bias against non-White physicians may impact physician satisfaction ratings, but this has not been widely studied.

Objective

To assess differences in patient satisfaction by physician race/ethnicity.

Design

A cross-sectional observational study.

Participants

Patients seeking care on a large nationwide direct to consumer telemedicine platform between July 2016 and July 2018 and their physicians.

Main Measures

Patient satisfaction was ascertained immediately following the encounter on scales of 1 to 5 stars and scored two ways: (1) top-box satisfaction (5 stars versus fewer) and (2) dissatisfaction (2 or fewer stars versus 3 or more). To approximate the information patients would use to make assumptions about physician race/ethnicity, four reviewers classified physicians into categories based on physician name and photo. These included White American, Black American, South Asian, Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and East Asian. Mixed effects logistic regression was used to assess differences in patient top-box satisfaction and patient dissatisfaction by physician race/ethnicity, controlling for patient characteristics, prescription receipt, physician specialty, and whether the physician trained in the USA versus internationally.

Key Results

The sample included 119,016 encounters with 390 physicians. Sixty percent were White American, 14% South Asian, 7% Black American, 7% Hispanic, 6% Middle Eastern, and 6% East Asian. Encounters with South Asian physicians (aOR 0.70; 95% CI 0.54–0.91) and East Asian physicians (aOR 0.72; 95% CI 0.53–0.99) were significantly less likely than those with White American physicians to result in top-box satisfaction. Compared to encounters with White American physicians, those with Black American physicians (aOR 1.72; 95% CI 1.12–2.64), South Asian physicians (aOR 1.77; 95% CI 1.23–2.56), and East Asian physicians (aOR 2.10; 95% CI 1.38–3.20) were more likely to result in patient dissatisfaction.

Conclusions

In our study, patients reported lower satisfaction with some groups of non-White American physicians, which may have implications for their compensation, professional reputation, and job satisfaction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Patient satisfaction measures have important implications for physicians. Public reporting of patient satisfaction may impact physician reputation or patient volume.1 An increasing number of physicians are compensated based on patient experience measures, including patient satisfaction.2 Poor responses on patient satisfaction surveys have also been found to negatively impact physician job satisfaction.3

Bias in healthcare occurs when patients or physicians use irrelevant personal characteristics, such as race/ethnicity, as the basis for assumptions, treatment recommendations, or appraisals of care. Physician bias against non-White patients has been widely documented,4,5,6 while patient bias against non-White physicians has been reported,7,8,9,10,11,12 but not well-studied. Bias may manifest via measures of patient satisfaction with physicians. A study in a large health system found patients reported lower satisfaction with international medical graduates 13 and another found older White patients expressed less satisfaction with foreign-trained physicians, compared with US-trained ones.14 Yet, two other studies found no difference in patient satisfaction ratings by physician race/ethnicity.15, 16 Overall, the literature addressing this issue is thin. Given the potential negative impact of poor patient satisfaction scores on physicians, a better understanding of the extent to which physician race/ethnicity may impact their satisfaction ratings is needed.

Direct to consumer (DTC) telemedicine is a rapidly expanding setting,17 wherein patients use electronic applications to connect with licensed physicians 24 h a day to address low-acuity health concerns. Unlike in primary care, where patients may select in advance a physician of a particular race/ethnicity based on their preferences,18 patients in DTC telemedicine are paired with physicians based on appropriateness and availability, although in some cases, patients may decide to wait longer for a different physician, assuming one is available. This is similar to the situation in urgent care or the emergency department, where patients have little say over which physicians care for them. As the threat of selection bias is lower than in outpatient care, DTC telemedicine is an ideal setting to explore variation in patient satisfaction by physician race/ethnicity.

The objective of this study was to assess differences in patient satisfaction by patient-perceived physician race/ethnicity in a large national DTC telemedicine platform.

METHODS

This study uses data from a large nationwide DTC telemedicine platform, details of which have been described previously.19 Encounters were conducted with board-certified physicians between July 2016 and July 2018. An encounter was defined as a completed telemedicine visit between a physician and a patient that concluded with the patient providing a satisfaction rating for the physician. There were no exclusions based on patient or encounter characteristics. To ensure the stability of estimates at the physician level, only physicians with at least 20 encounters were included.

This study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board.

Physician Race/Ethnicity

While self-reported race/ethnicity is the gold standard for studies aiming to understand the lived experiences of participants,20 our objective was different. We aimed to assess differences in patient satisfaction by patient-perceived physician race/ethnicity. Our rationale for this was that patient perceptions are what drive potential biases, irrespective of how a physician may self-identify racially or ethnically. To construct what the patient perceived, we used two key pieces of information telemedicine patients would typically use to inform their assumptions: the physician’s name and their appearance, as this is a video-based telemedicine service. The telemedicine platform provided the first and last name of each encounter physician. Four independent reviewers of diverse ages and racial/ethnic backgrounds (K.M., R.R., K.K., and J.R.), blinded to each other’s assessments, assigned each physicians’ perceived race/ethnicity based on their name and publicly available photo. For example, an apparently White physician named “John Smith” was assigned an ethnicity of White American, while a physician named “Mina Ling” was assigned an ethnicity of Asian. Physicians for whom agreement on race/ethnicity was less than three-fourths among reviewers were excluded.

For analysis, perceived race/ethnicity was categorized as White American, Black American, South Asian (e.g., Indian, Pakistani), Middle Eastern, Hispanic, and East Asian (e.g., Chinese, Korean). We selected these categories based on the reviewer consensus that these are probably distinct and meaningful categories to patients. While we identified other races/ethnicities (e.g., African), there were too few physicians in each category for meaningful analysis.

Medical Training

To account for differences in patient satisfaction which may have arisen as the result of differences in language and/or culture, we determined whether physicians attended a US or non-US medical school through an internet search of public records. We did this only for South Asian, Middle Eastern, East Asian, and Hispanic physicians. We assigned White American and Black American physicians to US medical schools. Although some may have trained at foreign institutions, we assumed they would not speak with accents and would be familiar with American culture, which was the purpose of this measure. We dichotomized this as US medical school versus international.

Patient Satisfaction

This was assessed immediately following the encounter by the telemedicine system. Patients were asked to rate their satisfaction with their telemedicine physician on scales of 1 to 5 stars with 5 stars being most satisfied. We treated this measure in two ways. First, we were interested in understanding differences by physician race/ethnicity in the proportion of patients reporting top-box satisfaction. For this, we dichotomized the rating as 5 stars versus fewer than 5 stars, which is consistent with our prior treatment of this measure,19, 21 as well as with Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) “top-box” scoring.22 Second, we were interested in the converse: what proportion of patients were dissatisfied with physicians. For this, we dichotomized the scale at 2 stars or fewer versus 3 stars and above, the former of which we considered dissatisfaction. Generally, patient responses to satisfaction measures are not normally distributed and cluster at higher ratings.23 Because ratings below 3 stars are rarer, we believe they represent patients who were particularly dissatisfied.

Control Variables

Patient characteristics included age, gender, and geographic region, based on those defined by the US Census. We also controlled for physician gender, specialty, and geographic region. We have previously found that prescription receipt is highly associated with patient satisfaction with telemedicine.19, 24 Patients appear to conflate receiving a prescription with receipt of high-quality care. Thus, in order to control what patients may perceive as differences in care quality, we also controlled for whether or not they received a prescription.

Statistical Analysis

We generated descriptive statistics for the sample and assessed the proportion of visits resulting in top-box satisfaction or dissatisfaction by physician race/ethnicity. Using mixed effects logistic regression, accounting for clustering by physician, we assessed differences in the odds of the telemedicine physician being rated top-box versus not, by physician race/ethnicity and whether they trained at a US or international medical school. Similarly, we assessed differences in the odds of the encounter physician being rated 2 or fewer stars (dissatisfaction), by physician race/ethnicity and medical school training location. Models adjusted for physician and patient geographic region; patient age and gender; physician gender and specialty; and whether the encounter concluded with a prescription. All analyses were conducted in Stata 14.

RESULTS

Initially, 440 physicians met the inclusion criteria. Overall, three-fourths agreement or more between reviewers on racial/ethnic categorization was met for 92% of physicians. In the 8% of cases where it was not, some physicians had names that were incongruent with their photo, such as is the case with some Filipino physicians who may have Spanish sounding surnames but East Asian appearances. In other cases, physicians had hyphenated last names that were not easily allocated into one racial/ethnic category (e.g., “Gonzalez-Tung.”) There were 16 physicians for whom there was over three-fourths agreement that were nonetheless excluded due to belonging to classifiable but narrow categories of ethnicities such as Greek, Eastern European, or African. There were too few physicians in each of these groups to form their own categories for analysis.

Ultimately, 390 (89%) of eligible physicians were classified into racial/ethnic categories by the study team, and among them, they conducted 119,016 encounters during the study period (Table 1). The majority (60%; n = 233) were classified by the study team as White American, 14% (n = 56) were South Asian, 7% (n = 27) were Black American, 7% (n = 27) were Hispanic, 6% (n = 24) were Middle Eastern, and 6% (n = 23) were East Asian. Most (87%; n = 338) physicians trained at a US medical school; 53% (n = 206) were female and 52% (n = 204) were family medicine physicians.

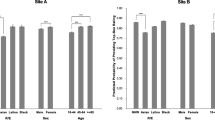

Overall, 73% of encounters had a patient satisfaction rating, ranging from 71% for encounters with East Asian physicians to 77% for encounters with Middle Eastern physicians (p < 0.001). The proportion of visits resulting in a top-box rating was 90% (n = 76,346) for visits with White American physicians, 89% (n = 7002) for Black American physicians, 88% (n = 4829) for Hispanic physicians, 87% (n = 4793) for Middle Eastern physicians, 82% (n = 7665) for South Asian physicians and 81% (n = 4427) for East Asian physicians. Eighty-nine percent of encounters (n = 96,579) with physicians who trained at a US medical school resulted in a top-box rating compared with 84% (n = 8483) of those with non-US-trained physicians. The proportion of encounters resulting in a dissatisfied rating was 2% (n = 1675) for White American physicians; 3% (n = 230) for Black American, Hispanic (n = 171), and Middle Eastern (n = 149) physicians, respectively; 5% (n = 495) for South Asian physicians; and 6% (n = 316) for East Asian physicians. The proportion of encounters resulting in a dissatisfied rating was 2% (n = 2667) for US-trained physicians compared with 4% (n = 369) for internationally trained physicians.

In the adjusted mixed effects logistic regression model of odds of a patient reporting top-box satisfaction (Table 2), encounters with South Asian physicians (aOR 0.70; 95% CI 0.54–0.91) and East Asian physicians (aOR 0.72; 95% CI 0.53–0.99) were significantly less likely to result in a top-box score than encounters with White American physicians. There was no statistically significant difference in the odds of a top-box score by US- versus internationally trained physicians.

Table 3 presents the adjusted mixed effects model estimating the odds of a patient reporting dissatisfaction with their physician. Compared with encounters with White American physicians, encounters with Black American physicians (aOR 1.72; 95% CI 1.12–2.64), South Asian physicians (aOR 1.77; 95% CI 1.22–2.56), and East Asian physicians (aOR 2.10; 95% CI 1.38–3.20) were significantly more likely to receive a dissatisfied rating. There was no difference in the odds of being dissatisfied with an encounter with Middle Eastern or Hispanic physicians, compared with an encounter with a White American physician, nor was there a statistically significant difference by medical school training location.

DISCUSSION

In our study in a large nationwide DTC telemedicine platform, patient satisfaction with physicians was high overall, yet we found significant differences in ratings by patient-perceived physician race/ethnicity. Encounters with South Asian and East Asian physicians were less likely to result in a top-box rating compared with encounters with White American physicians. Patients also expressed more dissatisfaction with Black American, South Asian, and East Asian physicians compared with White American physicians. This effect was persistent despite adjusting for whether the patient received a prescription, which has been shown to be the strongest predictor of satisfaction with telemedicine care.19 Our findings indicate that in DTC telemedicine, patients express somewhat less top-box satisfaction but considerably more dissatisfaction with some groups of non-White American physicians. This may have implications for these physicians’ compensation, reputation, and professional well-being.

While very few studies have explored this topic, two prior studies looking at differences in patient ratings by physician race/ethnicity used HCAHPS data. One found foreign medical graduates were less likely than US-trained physicians to receive top patient experience scores,13 while the other found no difference in ratings by physician race/ethnicity.15 Studies using HCAHPS data are limited in a number of ways. First, patients are asked about all physicians involved in their care, but scores are attached to their discharging physician. Patient experiences with their illnesses, particularly in the inpatient setting, can affect how they feel about their care;25 surveys are sent to patients weeks after discharge, so their memory of their interactions may be affected by recall bias. In contrast, DTC telemedicine surveys are administered immediately following the encounter. Moreover, HCAHPS tends to have a low response rate, and response rate bias tends to skew patient satisfaction ratings artificially high.26 In DTC telemedicine, patients see a single physician per encounter and they rate their satisfaction with that physician immediately, thereby increasing validity and response rate. Most patients seeking care via DTC telemedicine do so for low-acuity conditions (e.g., respiratory tract infections), likely resulting in less confounding by illness severity compared with HCAHPS.19 Finally, because we controlled for treatment outcome, e.g., prescription receipt, we can be further assured that the main difference between the telemedicine visits in our study was physician race/ethnicity and that this at least partially influenced patient satisfaction ratings.

Satisfaction is a highly skewed metric with most people reporting not only being highly satisfied but optimally satisfied (in our case, top-box). It is for this reason Uber decommissions drivers with less than a 4.6 rating.27 Thus, even small differences in the proportion of patients not rating physicians as top-box can meaningfully pull down a physician’s overall rating. Most patients are satisfied with healthcare unless there is some event that causes them to feel dissatisfaction.28 While some work has examined variation in patient complaints by physician age29 or gender,30 to our knowledge, ours is the first to assess differences in patient dissatisfaction by physician race/ethnicity. An analysis of dissatisfying events at an academic medical center found that problems with communication, perceived physician ineptitude, and disrespect were associated with patient dissatisfaction.31 Some patients may perceive problems with communication when being treated by non-White American physicians, or cultural differences may result in a patient feeling disrespected by physicians who are different from them. Whether these feelings are the result of systematic variation in physician behavior by race/ethnicity or culture is unknown. Yet, patient ratings of the quality of their care are largely driven by perception and are generally poorly correlated with the technical features of care.32, 33

In outpatient care, patients who have preferences for physician race/ethnicity can select physicians that fulfill these preferences. It is therefore difficult to assess potential patient bias against non-White physicians if the patients with the strongest racial/ethnic preferences already have them fulfilled. Studies conducted in outpatient care may result in weaker observed correlations between physician characteristics and patient satisfaction than might truly exist. In DTC telemedicine, patients have a very limited choice of physicians and are instead matched with physicians based on the appropriateness (e.g., if the patient is a child, then a pediatrician is needed) and availability. Our study results are therefore most generalizable to healthcare settings in which patients have little choice regarding physician characteristics, such as urgent or emergency care.

Physician-directed racism in healthcare has only recently begun receiving the attention it warrants. A recent qualitative study found non-White physicians were confronted with racial bias from patients ranging from explicit racist statements to subtler, yet meaningful, micro-aggressions.11 Whether physicians in our study were aware that their dissatisfied patients were dissatisfied is unknown, yet one could assume that encounters concluding with a 1 star rating probably were not good experiences for the physician either. Our study provides some evidence that certain groups of non-White American physicians may be exposed to negative patient encounters at a higher rate than others, leaving them susceptible to higher rates of burnout11, 34, 35 and other negative work-related outcomes.

Individuals form unconscious impressions of others immediately based on traits and assumptions. According to the stereotype content model, two of the strongest and most immediate of these impressions are a person’s perceived warmth and competence,36 and these perceptions are driven by stereotypes. In North America, Asians are perceived to be competent but not warm, Whites are perceived to be warmer but slightly less competent, and Middle Eastern individuals are perceived to be less competent and less warm.37 Emotions informed by these perceptions can result in discriminatory behavior—intentional or unintentional.38 This model has been used to understand patient perceptions of their physicians in traditional healthcare settings,39, 40 finding that perceptions of warmth and competence influence patient satisfaction with care.41, 42 Yet, in DTC telemedicine, where patients have no prior relationship with physicians, encounters are short, and communication is constrained to a virtual platform; patient perceptions related to warmth and competence based on racial/ethnic stereotypes may play an outsized role. As online care continues to grow, understanding how stereotype-informed perceptions of physician quality in this setting is needed.

This study had some limitations. We were unable to account for important factors that may have influenced patients’ assessment of their physicians’ race/ethnicity, like accent. While we attempted to do so by controlling for whether a physician trained at a US versus an international medical school, some of the physicians in our sample who trained in the USA may have been more recent immigrants to the USA and may have had accents. Additionally, some American physicians may have trained internationally. We lacked race/ethnicity information about the patients, which is important because race concordance between patients and physicians is associated with patient satisfaction.43 While we had a large number of encounters, our total number of non-White American physicians was relatively small, which limited our ability to do subgroup analyses. Patient expectations are associated with satisfaction,44 but given that telemedicine care is a fairly new setting, less is known about patient preferences for online care. Our findings may therefore not be generalizable to other settings.

Our study in DTC telemedicine found patients reported less top-box satisfaction and significantly higher dissatisfaction with some groups of non-White American physicians. Patient satisfaction measures are increasingly tied to physician compensation and poor reviews may result in negative physician well-being. Given we found systematic differences in patient ratings of care by physician race/ethnicity suggests that overreliance on these scores for non-White American physicians is potentially problematic.

References

Yaraghi N, Wang W, Gao G, Agarwal R. How Online Quality Ratings Influence Patients’ Choice of Medical Providers: Controlled Experimental Survey Study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(3):e99. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8986

Japsen B. More Doctor Pay Tied To Patient Satisfaction And Outcomes. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/06/18/more-doctor-pay-tied-to-patient-satisfaction-and-outcomes/#7c5d4823504a. Accessed July 17, 2019.

Zgierska A, Rabago D, Miller MM. Impact of patient satisfaction ratings on physicians and clinical care. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:437-446. doi:https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S59077

Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

Hall WJ, Chapman M V, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12):e60-e76. doi:https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302903

FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-017-0179-8

Reynolds KL, Cowden JD, Brosco JP, Lantos JD. When a Family Requests a White Doctor. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):381-386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2014-2092

Paul-Emile K, Smith AK, Lo B, Fernández A. Dealing with Racist Patients. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(8):708-711. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1514939

Jain SH. The Racist Patient. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(8):632. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-8-201304160-00010

Singh K, Sivasubramaniam P, Ghuman S, Mir HR. The Dilemma of the Racist Patient. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2015;44(12):E477-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26665247. Accessed August 1, 2019.

Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, et al. Physician and Trainee Experiences With Patient Bias. JAMA Intern Med. October 2019. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4122

Hu Y-Y, Ellis RJ, Hewitt DB, et al. Discrimination, Abuse, Harassment, and Burnout in Surgical Residency Training. N Engl J Med. October 2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1903759

Engelhardt KE, Matulewicz RS, DeLancey JO, et al. Physician characteristics associated with patient experience scores: implications for adjusting public reporting of individual physician scores. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(5):412-415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008346

Howard DL, Bunch CD, Mundia WO, et al. Comparing United States versus International Medical School Graduate Physicians Who Serve African- American and White Elderly. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(6):2155-2181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00587.x

Chen JG, Zou B, Shuster J. Relationship Between Patient Satisfaction And Physician Characteristics. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(4):177-184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2374373517714453

Solnick RE, Peyton K, Kraft-Todd G, Safdar B. Effect of Physician Gender and Race on Simulated Patients’ Ratings and Confidence in Their Physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e1920511. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.20511

Barnett ML, Ray KN, Souza J, Mehrotra A. Trends in Telemedicine Use in a Large Commercially Insured Population, 2005-2017. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12354

Traylor AH, Schmittdiel JA, Uratsu CS, Mangione CM, Subramanian U. The predictors of patient-physician race and ethnic concordance: a medical facility fixed-effects approach. Health Serv Res. 2010;45(3):792-805. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01086.x

Martinez KA, Rood M, Jhangiani N, et al. Patterns of Use and Correlates of Patient Satisfaction with a Large Nationwide Direct to Consumer Telemedicine Service. J Gen Intern Med. August 2018. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4621-5

Williams DR. Race/Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status: Measurement and Methodological Issues. Int J Health Serv. 1996;26(3):483-505. doi:https://doi.org/10.2190/U9QT-7B7Y-HQ15-JT14

Martinez KA, Rood M, Jhangiani N, Kou L, Boissy A, Rothberg MB. Association Between Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Tract Infections and Patient Satisfaction in Direct-to-Consumer Telemedicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(11):1558. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4318

Giordano LA, Elliott MN, Goldstein E, Lehrman WG, Spencer PA. Development, implementation, and public reporting of the HCAHPS survey. Med Care Res Rev. 2010;67(1):27-37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558709341065

Dunsch F, Evans DK, Macis M, Wang Q. Bias in patient satisfaction surveys: a threat to measuring healthcare quality. BMJ Glob Health. 2018;3(2):e000694.

Foster CB, Martinez KA, Sabella C, Weaver GP, Rothberg MB. Patient Satisfaction and Antibiotic Prescribing for Respiratory Infections by Telemedicine. Pediatrics. 2019;144(3). doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2019-0844

Thiels CA, Hanson KT, Yost KJ, Zielinski MD, Habermann EB, Cima RR. Effect of Hospital Case Mix on the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems Star Scores. Ann Surg. 2016;264(4):666-673. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001847

Mazor KM, Clauser BE, Field T, Yood RA, Gurwitz JH. A demonstration of the impact of response bias on the results of patient satisfaction surveys. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(5):1403-1417. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12479503. Accessed August 28, 2019.

Cook J. Uber’s internal charts show how its driver-rating system actually works. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/leaked-charts-show-how-ubers-driver-rating-system-works-2015-2. Accessed December 21, 2018.

Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(32):1-244. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12925269. Accessed August 1, 2019.

Fathy CA, Pichert JW, Domenico H, Kohanim S, Sternberg P, Cooper WO. Association Between Ophthalmologist Age and Unsolicited Patient Complaints. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2018;136(1):61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2017.5154

Unwin E, Woolf K, Wadlow C, Potts HWW, Dacre J. Sex differences in medico-legal action against doctors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2015;13(1):172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0413-5

Lee A V, Moriarty JP, Borgstrom C, Horwitz LI. What can we learn from patient dissatisfaction? An analysis of dissatisfying events at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):514-520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.861

Hong YA, Liang C, Radcliff TA, Wigfall LT, Street RL. What Do Patients Say About Doctors Online? A Systematic Review of Studies on Patient Online Reviews. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(4):e12521. doi:https://doi.org/10.2196/12521

Chang JT, Hays RD, Shekelle PG, et al. Patients’ Global Ratings of Their Health Care Are Not Associated with the Technical Quality of Their Care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(9):665. doi:https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-9-200605020-00010

Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Eacker A, et al. Race, Ethnicity, and Medical Student Well-being in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(19):2103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.19.2103

Peckham C. Medscape Lifestyle Report 2017: Race and Ethnicity, Bias and Burnout.; 2017. http://www.medscape.com/features/slideshow/lifestyle/2017/overview?src=WNL_physrep_170528_MSCPEDIT_lifestyle2017_spec&uac=205158CR&impID=1354762&faf=1#page=1.

Fiske ST. Warmth and Competence: Stereotype Content Issues for Clinicians and Researchers. Can Psychol. 2012;53(1):14-20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026054

Durante F, Fiske ST, Kervyn N, et al. Nations’ income inequality predicts ambivalence in stereotype content: How societies mind the gap. Br J Soc Psychol. 2013;52(4):726-746. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12005

Cuddy AJC, Fiske ST, Glick P. The BIAS map: Behaviors from intergroup affect and stereotypes. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2007;92(4):631-648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.631

Ashton-James CE, Tybur JM, Grießer V, Costa D. Stereotypes about surgeon warmth and competence: The role of surgeon gender. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0211890. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0211890

Howe LC, Leibowitz KA, Crum AJ. When Your Doctor "Gets It" and "Gets You": The Critical Role of Competence and Warmth in the Patient-Provider Interaction. Front psychiatry. 2019;10:475. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00475

Kenny D t. Determinants of patient satisfaction with the medical consultation. Psychol Health. 1995;10(5):427-437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08870449508401961

Kraft-Todd GT, Reinero DA, Kelley JM, Heberlein AS, Baer L, Riess H. Empathic nonverbal behavior increases ratings of both warmth and competence in a medical context. PLoS One. 2017;12(5):e0177758. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0177758

Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296-306. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12467254. Accessed September 1, 2017.

Sofaer S, Firminger K. Patient perceptions of the quality of health services. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:513-559. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.050503.153958

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

This study was approved by the Cleveland Clinic’s Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Prior Presentation

This was presented as a poster at the Society of General Internal Medicine Annual Meeting 2019 in Washington D.C. and at the AcademyHealth Annual Research Meeting 2019 in Washington D.C.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Martinez, K.A., Keenan, K., Rastogi, R. et al. The Association Between Physician Race/Ethnicity and Patient Satisfaction: an Exploration in Direct to Consumer Telemedicine. J GEN INTERN MED 35, 2600–2606 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06005-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06005-8