Abstract

Purpose

Low-grade glioma (LGG) patients may face health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) impairments, due to the tumour, treatment and associated side-effects and prospects of progression. We systematically identified quantitative studies assessing HRQoL in adult LGG patients, for: aspects of HRQoL impacted; comparisons with non-cancer controls (NCC) and other groups; temporal trends; and factors associated with HRQoL.

Methods

MEDLINE, CINAHL, Embase, PubMed, and PsycINFO were systematically searched from inception to 14th September 2021. Following independent screening of titles and abstracts and full-texts, population and study characteristics, and HRQoL findings were abstracted from eligible papers, and quality appraised. Narrative synthesis was conducted.

Results

Twenty-nine papers reporting 22 studies (cross-sectional, n = 13; longitudinal, n = 9) were identified. Papers were largely good quality, though many excluded patients with cognitive and communication impairments. Comparators included high-grade gliomas (HGG) (n = 7); NCCs (n = 6) and other patient groups (n = 3). Nineteen factors, primarily treatment (n = 8), were examined for association with HRQoL. There was substantial heterogeneity in HRQoL instruments used, factors and aspects of HRQoL assessed and measurement timepoints. HRQoL, primarily cognitive functioning and fatigue, in adult LGG patients is poor, and worse than in NCCs, though better than in HGG patients. Over time, HRQoL remained low, but stable. Epilepsy/seizure burden was most consistently associated with worse HRQoL.

Conclusion

LGG patients experience wide-ranging HRQoL impairments. HRQoL in those with cognitive and communication impairments requires further investigation. These findings may help clinicians recognise current supportive care needs and inform types and timings of support needed, as well as inform future interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Plain English Summary

Low-grade gliomas are brain tumours most commonly diagnosed in working-aged adults. Brain tumour patients can experience numerous symptoms, such as communication impairment and mobility issues, which can impact their quality of life. Patients with low-grade gliomas have a longer life expectancy than patients with other, high-grade brain tumours, though they are rarely cured. Therefore, it is important to understand how their quality of life is impacted in the extended periods living with a low-grade glioma. We looked at which aspects of health-related quality of life were impacted; how health-related quality of life compared with other patient populations; whether health-related quality of life changed over time; and whether any factors (e.g. age) influenced health-related quality of life. We found that low-grade glioma patients experience wide-ranging health-related quality of life impairments, particularly fatigue and cognitive impairment, that remains poor, but does not change much over time. Though better than in high-grade gliomas, health-related quality of life was worse than in people without cancer and was influenced by several factors, most frequently seizures. This means low-grade glioma patients may live for long periods with poor health-related quality of life. Our findings may help clinicians recognise what these patients’ supportive care needs are, and what support is needed.

Introduction

Worldwide, in 2020, there were approximately 300,000 new brain and central nervous system tumours diagnosed [1]. Gliomas – which may be high- or low-grade—are the most common malignant tumour of the brain [2]. Low-grade gliomas (LGG) account for approximately 15% of all gliomas, with an incidence rate of around 1/100,000; they are mostly diagnosed in adults in their 30 s and 40 s [3]. Depending on the subtype, life expectancy of LGG patients is limited to about 5–15 years [3, 4]. However, LGGs are rarely cured, and typically recur or progress to a high-grade glioma (HGG) [5]. Thus, LGG patients may live for extended periods with a ‘terminal’ condition.

Health-related quality-of-life (HRQoL) is a multidimensional construct that comprises the ability to perform everyday activities, as well as patient satisfaction with levels of functioning and disease control [6]. Brain tumour patients can experience an array of symptoms, often occurring in clusters and deteriorating as the disease progresses [7]. These include general cancer-related symptoms (e.g. fatigue, pain), and tumour-specific symptoms (e.g. cognitive limitations, seizures, speech, language, and communication impairments, personality changes and mobility issues) [8,9,10]. These symptoms can contribute to changes in social roles, daily functioning, and loss of independence, which adversely impact physical and psychosocial HRQoL [10, 11].

Studies suggest there are numerous factors (e.g. age, tumour location, and time since diagnosis), that could influence brain tumour patients’ HRQoL [12]. Gaining a comprehensive understanding, from across the literature of how these factors are associated with HRQoL and how HRQoL changes over time, may help to ascertain in whom, what, and when, support is necessary and identify target areas for future interventions.

It is, however, difficult to distinguish the extent these problems are experienced by LGG patients. One issue is sample heterogeneity; studies often group patients with LGGs, HGGs, and other primary brain tumours [13,14,15]. This limits our understanding of the HRQoL impact of living long-term with a tumour that is still likely to progress. Further, much of the evidence comes from treatment trials. Trial populations are often highly selected and have a lower risk profile than ‘real-world’ patient populations [16]. Treatment modalities (e.g. surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy) have been associated with HRQoL in LGG patients [17,18,19]. Thus, HRQoL impairments may be due to the tumour or its treatment. Consequently, there is a need to better understand the ‘real world’ impact of an LGG on HRQoL, outwith the trial context.

We, therefore, conducted a systematic review to examine how HRQoL is impacted in adults with an LGG, by establishing: (1) which aspects of HRQoL are impacted; (2) how HRQoL compares with other populations; (3) temporal trends in HRQoL; and (4) factors associated with HRQoL. Our secondary aims were to assess quality of, and identify gaps or limitations in, the available evidence.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with the Prospective Register for Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (CRD42021231368) and conducted and reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [20].

Definition

For the purposes of this review, we defined HRQoL as “the subjective perceptions of the positive and negative aspects of cancer patients’ symptoms, including physical, emotional, social, and cognitive functions and, importantly, disease symptoms and side effects of treatment.”[21] Hereafter, ‘global HRQoL’ indicates total scores, while ‘specific (aspects of) HRQoL’ indicates functioning and symptoms.

Eligibility criteria

A paper was eligible if: (1) it was a primary, peer-reviewed research article, available in English; (2) participants were adults (≥ 18-years old), diagnosed with an LGG; (3) data were from an observational study conducted in a ‘real-world’ setting (i.e. in routine practice, outwith the clinical trial context); (4) an instrument was used to quantitatively assess HRQoL, with evidence of content validity or other psychometric properties. Papers which focused on a single issue (e.g. psychological wellbeing) were eligible if the issue was framed, in the paper, as an aspect of HRQoL.

A paper was excluded if: (1) the sample was heterogenous (e.g. included HGGs) and LGGs were not a distinct group; (2) the HRQoL findings were not reported; (3) participants were adult survivors of childhood diagnoses (< 18-years); or (4) data were from a trial directly investigating specific treatments (e.g. impact of radiotherapy).

Search strategy

On 10th December 2020, we searched five electronic databases from inception: MEDLINE, Embase, PsycINFO, CINAHL, and PubMed. The search strategy concerned two key concepts: LGG and HRQoL. Assisted by a Senior Library Assistant, a combination of Medical Subject Headings and keywords were formulated, informed by the literature (Supplementary Table S1). LGG was searched using general terms and specific tumours, in line with the 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system [22]. The 2021 WHO classification update [23] succeeded initial database searches, though our search strategy still encompassed LGGs, as they are now classified. HRQoL was searched using general terms and terms for HRQoL instruments that were previously reported to have been used in brain tumour patients [24] (although studies did not have to have used these instruments to be eligible). The search strategy was adapted accordingly for each database (Supplementary Table S2).

Reference lists and forward citations of eligible papers and relevant reviews were hand-searched to identify additional papers not retrieved through the database searches. The search was updated on 14th September 2021.

Paper selection

Once duplicates were removed, B.R and I.B independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by full texts of papers considered potentially eligible by either reviewer. The process was blinded until both reviewers completed each stage of screening. Discrepancies at paper selection were resolved through discussion with co-authors (L.D and L.S).

Data extraction and quality appraisal

Data extraction was conducted and cross-checked (shared between B.R and I.B), using a structured form. The following data were extracted: general: name of first author, year published, country; study population: eligible population, sample size, participant characteristics, namely, age, sex, ethnicity, socio-economic status (SES), Karnofsky performance status (KPS), tumour type and location, genetic markers, treatment, time since diagnosis/treatment; study design: design, comparator/control populations, HRQoL measurement timepoints, HRQoL instrument(s) used and specific aspects of HRQoL assessed, clinical and epidemiological factors examined for association with HRQoL; findings: global HRQoL, specific HRQoL, HRQoL in comparators/controls, HRQoL over time (e.g. mean scores), and factors associated with HRQoL (e.g. correlation coefficients).

If more than one paper reported the same sample, then characteristics and findings were pooled as one study. Corresponding authors were contacted to request relevant missing information. No reply within three weeks meant data extraction decisions were informed by the available published material. Discrepancies at data extraction were resolved through discussion between co-authors (B.R and I.B).

Included papers were quality appraised and cross-checked (shared between B.R and I.B), using the 12-item critical appraisal checklist, established by Dunne et al. [25] in a previous systematic review on quality-of-life in cancer survivors. Items included ‘main features of population/design described’ and ‘measures relevant, validated, and described adequately’. Each item was scored 0 (no), 1 (partial) or 2 (yes). Potential scores ranged from 0–24, with 0–8 indicating ‘low quality’, 9–16 ‘acceptable quality’, and 17–24 ‘good quality’.

Data synthesis and analysis

Eligible studies were included in a narrative synthesis [26]. This was structured around the study population, design, quality appraisal, and HRQoL assessment, namely: global and specific HRQoL, population comparisons, temporal trends, and associated factors. Aspects of HRQoL which are included in the relevant instrument(s), but which were not reported by authors, were abstracted as ‘not reported’.

To interpret HRQoL, we used previously reported reference values; these were available for EORTC QLQ-C30 [27], EQ-5D [28], and FACT-G [29]. Otherwise, judgements were based on interpretations of the original authors; here, to ensure consistency, a value interpreted as ‘poor’ in one study, was considered ‘poor’ across all other studies which used the same instrument (there were no instances of different interpretations for values by authors of the papers). To synthesise the interpreted values for specific aspects of HRQoL, studies were grouped when different studies/instruments reported a dimension with the same (e.g. fatigue) or similar label (e.g. emotional wellbeing/functioning). In the synthesis, papers were “weighted” equally irrespective of the quality appraisal results.

Results

Search results

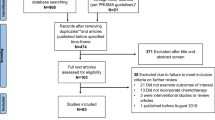

Database searches identified 3295 papers, with 2037 remaining following deduplication. Full texts of 132 papers were assessed for eligibility, with 26 papers deemed eligible. Hand searches identified three additional papers. Twenty-nine papers reporting on 22 studies were included [12, 30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57] (Fig. 1).

Study population

Studies were conducted across 13 countries: three each in the Netherlands [12, 30,31,32, 44, 48] and USA [33, 36, 37, 39], two each in China [42, 54,55,56], Italy [35, 45], India [34, 46], Japan [47, 53], and Norway [38, 41], and one each in Australia [52], Finland [50, 51], Germany [49], South Korea [43], Sweden [40], and Turkey [57] (Table 1; Supplementary Table S3). Sample size ranged from 15 to 260. Mean age was typically late 30 s and 40 s. Sex ranged from 24 to 73% female. Only Affronti et al. [33] reported ethnicity, for a predominantly white (93%) sample. Eleven studies reported SES [12, 35, 36, 39, 42, 44, 45, 48, 49, 54, 57] assessed through education, employment, or insurance status. Nine studies reported KPS [12, 33, 38, 41, 47,48,49, 54, 57]; scores ranged 60–100, but were mostly ≥ 80.

Tumour details included: grade (n = 5 studies) [31, 43, 52, 54, 57]; type (n = 12) [31, 33, 36, 40,41,42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 52, 53], predominantly astrocytoma, oligodendroglioma, and oligoastrocytoma; laterality (n = 13) [31, 33, 35, 36, 38, 39, 42, 44, 45, 49, 52, 54, 57]; and location (n = 12) [31, 33, 35, 36, 39, 42, 44, 45, 47,48,49, 57], largely frontal lobe. Four studies reported genetic markers [33, 42, 45, 53]. Sixteen studies reported treatment [12, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40,41,42, 44, 45, 47, 48, 50, 52, 54, 57], including chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and extent of surgical resection. Time since diagnosis/treatment at which HRQoL was assessed ranged from point of diagnosis to 20-years since treatment. Heterogeneity was common within studies; e.g. participants in Correa et al. [36] ranged from six- to 118-months (9.83 years) since treatment.

Study design

Thirteen studies were cross-sectional [34, 35, 39,40,41,42,43,44, 46,47,48,49, 53] and nine longitudinal [31, 33, 37, 38, 45, 51, 52, 54, 57], assessing HRQoL at several (albeit varied) timepoints (Table 2). Thirteen studies included a comparator and/or control group, comprising: HGG patients (n = 7) [34, 38, 39, 43, 45, 46, 53], non-cancer controls (NCC) (n = 6) [12, 35, 44, 48, 49, 52], or benign brain tumour [34], suspected LGG [48], or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)/chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) patients [12].

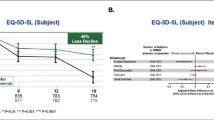

Thirteen different general, cancer-related, brain tumour-specific, or unidimensional HRQoL instruments were used, predominantly: EORTC QLQ-BN20 (n = 8) [12, 34, 41, 46,47,48, 53, 57], EORTC QLQ-C30 (n = 8) [34, 40, 41, 46, 47, 52, 53, 57], SF-36 (n = 6) [12, 42, 44, 45, 48, 49], FACT-Br (n = 3) [33, 36, 54], and EQ-5D (n = 2) [38, 41]. Eleven studies used multiple HRQoL instruments [12, 33,34,35, 39, 41, 46,47,48, 50, 53, 57], often combining general (e.g. SF-36) or cancer-related (e.g. QLQ-C30), with brain tumour-specific (e.g. QLQ-BN20) instruments. The HRQoL instruments used, specific dimensions assessed by each, and their scoring, is detailed in Supplementary Table S4. Fourteen studies assessed global HRQoL [33, 34, 36, 38, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47, 51,52,53,54, 57] with one of the six instruments (e.g. FACT-G) with a possible global HRQoL score. Once grouped, frequently assessed HRQoL dimensions included: physical (n = 19 studies) [12, 33, 34, 36, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 52,53,54, 57], social (n = 18) [12, 33, 34, 36, 40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49, 52,53,54, 57], emotional (n = 13) [33, 34, 36, 39,40,41, 43, 46, 47, 52,53,54, 57], and cognitive functioning (n = 10) [33, 39,40,41, 46, 47, 52, 53, 57], as well as pain (n = 17) [12, 34, 38,39,40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 52, 53, 57], and fatigue (n = 10) [33, 34, 39,40,41, 46, 47, 52, 53, 57].

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal scores ranged from 15 to 21 of a possible 24, with 20 papers considered ‘good quality’ [12, 30,31,32, 35, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47, 49, 53,54,55,56] and nine ‘acceptable quality’ [33, 34, 36, 37, 48, 50,51,52, 57] (Table 2; Supplementary Table S5). Aaronson et al. [12], Boele et al. [31], Drewes et al. [38], and Wang et al. [54] were the highest quality papers, each scoring 21. Primary reasons for lower scores included: failure to clearly document participant eligibility and recruitment (e.g. 11 papers (eight studies) excluded cognitively and/or communication impaired patients without detailing how this was determined) [12, 30,31,32, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 53, 57]; and lack of a control and/or comparator group.

Health-related quality-of-life findings

Health-related quality-of-life

The dimensions measured and how scores are determined across the 11 multidimensional and two unidimensional HRQoL instruments reported in the studies is quite different (Table 2; Supplementary Table S4). HRQoL values were not reported for all potential instrument dimensions in 13 studies [34,35,36, 41,42,43,44,45,46, 48,49,50, 52]; below, the denominator is the number of studies that reported a value for a specific dimension.

Global HRQoL

Thirteen (of 14) studies reported poor global HRQoL in LGG patients (i.e. QLQ-C30 score 61.9–74) [33, 34, 36, 38, 40, 41, 43, 46, 47, 52,53,54, 57] that was significantly worse than in NCCs (n = 1 of one) [52], though significantly better than in HGG patients (n = 4 of five) [34, 38, 43, 46] (Table 3; Supplementary data).

Specific HRQoL – functioning

Seventeen studies reported values for functioning aspects of HRQoL in LGG patients [12, 33, 34, 39,40,41,42, 44,45,46,47,48,49, 52,53,54, 57]. Poor functioning was reported across numerous HRQoL aspects. Cognitive functioning was poor in seven (of 10) studies [33, 34, 39,40,41, 52, 57], and significantly worse than NCCs in one (of one) of these [52]. Poor emotional functioning was reported in five (of 11) studies [33, 34, 40, 52, 54] and was significantly worse than NCCs in one (of one) of these [52]. General health perception was poor in four (of five) studies [12, 42, 48, 49]; four (of four studies with an NCC group) found it was significantly worse in LGG patients than in NCCs [12, 44, 48, 49]. Poor vitality was reported in four (of five) studies [12, 42, 48, 49]; three (of four studies with an NCC group) found it was significantly worse than in NCCs [12, 44, 48], as well as suspected LGGs in one (of one) of these [48].

Compared to NCCs, studies also reported significantly worse physical functioning (n = 4 of five) [12, 44, 49, 52] and emotional role functioning (n = 3 of four) [12, 44, 49] in LGG patients. Compared to HGG patients, of seven studies, only Mahalakshmi et al. [46] found significant differences, namely that LGG patients reported better emotional, physical, and social functioning.

Across studies, functioning aspects with the worst scores were cognitive functioning (n = 6) [39, 41, 46, 47, 52, 57], functional wellbeing (n = 2) [33, 54], general health perception (n = 2) [42, 49], social functioning (n = 2) [34, 53], vitality (n = 2) [12, 48], role functioning [40], and SF-36 mental [44] and physical [45] component scores. Still, ‘worst scores’ is a function (in part) of instrument used and what study authors choose to report, as cognitive functioning was either not assessed or reported in seven of the 11 studies that reported another aspect as having the worst score.

Specific HRQoL – symptoms

Fourteen studies reported values for HRQoL symptoms [12, 33, 34, 39,40,41,42, 46,47,48,49,50, 53, 57]. Considerable symptom burden was evident, most notably high levels of fatigue (reported in n = 8 of nine studies) [33, 34, 40, 41, 46, 47, 53, 57]. Other symptoms with substantial burden included: communication deficits (n = 7 of eight) [12, 34, 41, 46,47,48, 53]; future uncertainty (n = 6 of eight) [12, 41, 46,47,48, 53]; suffering from headaches (n = 5 of seven) [31, 34, 47, 48, 57]; financial difficulties (n = 5 of five) [40, 46, 47, 53, 57]; drowsiness (n = 4 of seven) [31, 47, 53, 57]; insomnia (n = 4 of five) [34, 39, 40, 57]; pain (n = 4 of 12) [34, 39, 40, 42]; and motor dysfunction (n = 3 of eight) [34, 41, 46]. The two studies that compared pain in LGG patients with NCCs were inconsistent [12, 44]. One study found motor dysfunction was significantly worse in LGG patients than those with suspected LGGs [48].

Again, compared to HGG patients, significant differences were primarily reported by Mahalakshmi et al. [46]; LGG patients had lower levels of communication deficit, distress from hair loss, fatigue, nausea/vomiting, pain, seizures, and suffering from headaches, though greater financial difficulties.

Across studies, symptoms with the worst scores were fatigue (n = 6) [33, 34, 40, 41, 47, 57], sleep disturbances (n = 2) [39, 50], drowsiness [53], financial difficulties [46], future uncertainty [12], and seizures [48]. This may be influenced by instrument used, as fatigue (n = 10) was the second most assessed symptom.

Health-related quality-of-life over time

Longitudinal studies varied in the timepoints at which they measured HRQoL. Four of nine longitudinal studies (which considered different aspects of HRQoL) suggested HRQoL remains low, but stable, over time, specifically over six-months [38], one-year [37], and up to 10-[52] and 12-years since diagnosis or treatment [31] (Table 3).

Global HRQoL changes

In Wang et al. [54] and Yavas et al. [57], global HRQoL improvements were reported over one- and three-years since treatment, respectively. For Yavas et al. [57], the median improvement was consistent with the EORTC QLQ-C30 definition of a minimally important difference (i.e. 4–6 points) for global HRQoL improvement in glioma patients [58].

Specific HRQoL changes

For Wang et al., emotional and functional wellbeing, and FACT-Br brain tumour subscale scores significantly improved at one-year, compared to one-month since treatment [54]. In Yavas et al., future uncertainty, communication deficit, suffering from headaches, drowsiness, and distress from hair loss significantly improved from initial assessment (end of radiotherapy) to three-years since treatment [57]. For Boele et al., with longer term follow-up, SF-36 physical functioning and physical component scores worsened between a mean of 5.6 and 12 years since diagnosis [31].

Factors associated with health-related quality-of-life

Eighteen papers reporting 15 studies [12, 30, 33,34,35, 38, 40,41,42, 44, 45, 47, 49, 52, 54,55,56,57] examined 19 different factors for association with HRQoL, most often: age (n = 8 studies) [12, 34, 35, 40, 45, 47, 49, 54], treatment (n = 8) [12, 34, 35, 38, 45, 47, 54, 57], and tumour location (n = 7) [12, 34, 35, 41, 45, 49, 54]. Significant associations were observed by at least one study for 17 factors (i.e. all except genetic markers and marital status) (Table 4). For eight factors—age, cognitive function, education, sex, SES, time since diagnosis/treatment, treatment, and tumour location—reported associations were not always statistically significant; the remaining nine factors – coping, depression, duration of symptoms, epilepsy/seizure burden, history of recurrence, KPS, post-traumatic growth, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and tumour type—were significantly associated with HRQoL in all studies in which they were reported.

There were 10 positively associated factors, with the most supporting evidence for KPS (n = 3 of three). Higher KPS was positively associated with global (n = 2) [34, 47] and specific HRQoL (e.g. less fatigue) (n = 2) [47, 49]. There were 12 negatively associated factors, with the most supporting evidence for epilepsy/seizure burden (n = 5 of five). Greater burden was negatively associated with global [54] and specific HRQoL (e.g. worse social functioning) (n = 4) [12, 35, 44, 49].

Five factors, namely, age, cognitive function, time since diagnosis/treatment, treatment, and tumour location were positively and negatively associated with HRQoL. For example, older age was positively [47] and negatively [12] associated with specific symptoms (e.g. diarrhoea and visual disorder, respectively).

Discussion

Summary of main findings

This systematic review aimed to identify quantitative evidence assessing HRQoL in adult LGG patients, to establish which aspects of HRQoL were impacted; how HRQoL compared with other populations; temporal trends; and factors associated with HRQoL. The 29 papers identified relating to 22 studies were largely good quality. Thirteen studies included comparator and/or control groups, and 19 factors were examined. Overall, the evidence-base suggests global HRQoL in LGG patients is poor, with considerable functioning impairments and symptom burden, most notably, cognitive functioning and fatigue, respectively. Over time, HRQoL remained low, but stable, and was better than in HGG patients, but substantially worse than in NCCs. Seventeen factors, most frequently epilepsy/seizure burden, were positively (n = 10 factors) or negatively (n = 12) associated with HRQoL.

Health-related quality-of-life

Thirteen different HRQoL instruments were used. Given the variation across instruments and heterogeneity in patient samples and times at which HRQoL was assessed, we decided not to conduct a meta-analysis. We support Fountain et al.’s call, made in 2016, for a standardised set of validated HRQoL measures for future LGG studies [59]. However, since 2016, 11 studies in this review used 11 different instruments. Hence, this issue is ongoing and needs to be addressed.

Despite better HRQoL than in HGG patients, poor HRQoL in LGG patients was consistently reported, and was emphasised when compared to NCCs. Notable functioning impairments were observed for cognitive, emotional, physical role, and social functioning, general health perception, mental health, and vitality. Symptom burden was high for communication deficit, fatigue, future uncertainty, pain, and suffering from headaches. Cognitive functioning and fatigue were consistently the functioning aspect and symptom with the most impairment and burden, respectively.

Comparisons within LGG subtypes were not investigated in the eligible studies. Survival rates vary by subtype; 1–10 year survival is markedly higher in oligodendrogliomas (93.9 to 64%), than diffuse astrocytomas (72.2 to 37.6%) [3]. It is possible quality of survival also varies. Future research should compare HRQoL across LGG subtypes to distinguish whether impairments or symptoms are accentuated in particular tumour types. The EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values for brain tumours are worse than other cancers (i.e. breast and colorectal) [27]. However, research comparing HRQoL in LGG patients to other (non-brain) cancer populations is scarce. Such comparisons would be of value to help determine whether more tumour-specific, or targeted, supportive care services are required.

There was substantial heterogeneity in time since diagnosis/treatment at which HRQoL was assessed, from point of diagnosis to 20-years since treatment. In general, studies which included patients closer to diagnosis reported greater impacts on HRQoL, as sufficient time may not have elapsed to adjust. For example, in Jiang et al. [42], which included patients approximately 3-months post-diagnosis, SF-36 scores were considerably lower than in other studies. Assessing HRQoL in early stages post-diagnosis may also be problematic. Ruge et al. [49] abandoned the BN20 because LGG patients did not want to be prospectively confronted with questions about treatment effects and tumour progression.

Health-related quality-of-life over time

There was considerable heterogeneity in timepoints assessed across longitudinal studies, with follow-up from one-month to 12-years since diagnosis. Post-treatment, HRQoL typically remained stable over time. However, largely poor baseline scores mean this is not an encouraging finding; rather it suggests LGG patients experience sustained HRQoL impairments over extended periods. Observed improvements to global and specific HRQoL were largely in comparison to one-month post-treatment and probably reflect dissipation of the more acute side-effects of adjuvant therapies [45]. Time for adjustment to the diagnosis is also important, and likely influences the temporal trends; acceptance has been associated with reduced general, and cancer-related, distress [60].

The longitudinal evidence is limited by failure to account for tumour progression or recurrence. Investigators tend not to make any accommodation in their results for the fact that some people have dropped out. Drewes et al. [38] gave deceased patients at follow-up a score of zero, which drove down their mean scores. In general, within these studies, observed temporal trends may, therefore, be biased by the dropout of those whose tumours have progressed and who might plausibly have worse HRQoL. This means more clarity is needed on how long HRQoL impairments are sustained, if, and when, they alleviate, and which aspects remain impaired over time.

Factors associated with health-related quality-of-life

Eight factors were positively associated, while four factors were negatively associated, with global HRQoL. Five factors were positively associated, while 12 factors were negatively associated with specific aspects of HRQoL. Epilepsy/seizure burden was most consistently associated with worse HRQoL suggesting further seizure management, as a clinical priority, may ameliorate the impact of an LGG on patient HRQoL.

Eight factors had inconsistent findings, most notably, age, sex, treatment, and tumour location. Nonetheless, acknowledging these factors is important when considering what support may be needed. For example, PTSD was associated with worse global HRQoL [56], and worse functioning on all eight SF-36 dimensions [42]. Consequently, LGG patients with PTSD may benefit from enhanced supportive care.

Critical appraisal of evidence

Twenty of the 29 papers were judged good quality. However, an important limitation is that the available evidence for HRQoL in adult LGG patients may not represent the full LGG population. Eleven studies explicitly excluded patients with communication and/or cognitive impairments. Only Drewes et al. [38] facilitated their inclusion, but this was through proxy ratings, which may not be reliable [61]. Eight studies failed to detail how impairments were determined [12, 38, 40, 42, 44, 46, 53, 57]. Gabel et al. [39] used the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination [62], and Wang et al. [54] used the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) [63] to assess communication and cognitive impairments, respectively. Though indicative of impairment, this should not determine someone’s capacity to participate. Wang et al. [54] excluded patients with at least mild cognitive impairment (≤ 24), yet lower MMSE scores are significantly associated with worse HRQoL in brain tumour patients [64]. Therefore, the average HRQoL of LGG patients was likely overestimated.

Consistent with Brownsett et al. [65], we highlight the prevalence of poor cognitive functioning and high levels of communication deficit in adult LGG patients. However, explicit exclusion of patients with these impairments in over half of studies, means these impacts may be underestimated. For those that did not exclude such patients, if/how participation was facilitated was often unclear. Miscomprehension of a question due to such impairments could impact the reliability of results. Future research should do more to facilitate greater inclusivity. To achieve this, researchers might engage in supportive conversation training; ensure accessible formatting of study documentation; validate accessible (e.g. pictorial) rating scales (see the assessment for living with aphasia [66]); or involve/consult specialist professionals, such as speech and language therapists.

The WHO classification of tumours of the central nervous system was majorly restructured in 2016 [22], and 2021 [23]. Included studies were published 2001 to 2021, so what authors considered to be an LGG is potentially heterogeneous. Seven studies did not report tumour type [34, 35, 38, 39, 46, 48, 50], while three studies only reported tumour grade [43, 54, 57]. This may have implications for whether HRQoL findings accurately reflect LGG patients, as presently classified. Details of anti-cancer treatment(s), ethnicity and SES for study samples were also incompletely reported, which limits understanding of whether HRQoL vary by these factors. A minimum “core set” of socio-demographic, tumour, and treatment-related characteristics to be consistently reported by future study authors would be valuable.

Strengths and limitations

Our review benefitted from extensive searches, including several databases and hand searching of reference lists and citations. Our focus on HRQoL beyond the clinical trial context allowed us to examine the ‘real world’ experience of LGG patients, when they are not undergoing the close monitoring that may happen within a trial.

A challenge was the lack of validated cut-off values for what is considered low, high, or clinically significant for numerous HRQoL instruments. Consequently, although we attempted to be consistent across studies, interpretation of reported values was difficult for some studies.

Brain tumour patients are likely to underestimate cognitive, emotional, psychological, and social changes [67]. This highlights an issue with subjective measurement of HRQoL using patient-reported outcome measures in LGG patients, namely that, because of the tumour, patients may lack insight and not self-report issues. This could mean functioning and symptoms have been over and underestimated, respectively, in the available studies.

Future research

The international classification of functioning, disability, and health (ICF) has been used to consider 44 categories of activities and participation (e.g. walking or doing housework) that may be limited in primary brain tumour patients [68]. Future research could be conducted to understand whether, and if so, which HRQoL impairments, personal (e.g. age), clinical (e.g. tumour location), and environmental (e.g. location) factors are associated with these categories in LGG patients. This could help to further highlight specific support needs of this population overall, and subgroups within it. To do this, a useful first step would be to code the HRQoL instrument items to the ICF.

To date, one qualitative study has explored HRQoL in LGG patients [69], and this focussed largely on coping strategies used. Further qualitative research would be of value to provide a more holistic insight into patients’ experiences of HRQoL impacts, functional impairments, and symptoms, and how different impacts might be interconnected. Patients could reflect on when HRQoL aspects were particularly impacted, at what point these improved or deteriorated, and valuable (in)formal support.

Conclusion

Influenced by several factors, most frequently, epilepsy/seizure burden, adult LGG patients have poor global HRQoL and experience an array of functioning impairments and symptom burden, most notably cognitive functioning and fatigue, respectively. These remain poor, but stable over time, and are markedly worse than in NCCs. Further consideration of LGG patients with speech, language, communication, and cognitive impairments is required, including steps to improve researchers’ confidence in ensuring their inclusion. These findings may help clinicians recognise current supportive care needs and inform types and timings of support needed, as well as inform future interventions.

References

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., & Bray, F. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020 GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(3), 209–249.

Miller, K. D., Ostrom, Q. T., Kruchko, C., Patil, N., Tihan, T., Cioffi, G., Fuchs, H. E., Waite, K. A., Jemal, A., & Siegel, R. L. (2021). Brain and other central nervous system tumor statistics, 2021. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 71(5), 381–406.

Bauchet, L. (2017). Epidemiology of diffuse low grade gliomas. In Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults (pp. 13–53). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-55466-2_2

Dixit, K., & Raizer, J. (2017). Newer Strategies for the Management of Low-Grade Gliomas. Oncology (Williston Park, N.Y.), 31(9), 680–682, 684–685. https://www.scholars.northwestern.edu/en/publications/newer-strategies-for-the-management-of-low-grade-gliomas

Claus, E. B., Walsh, K. M., Wiencke, J. K., Molinaro, A. M., Wiemels, J. L., Schildkraut, J. M., Bondy, M. L., Berger, M., Jenkins, R., & Wrensch, M. (2015). Survival and low-grade glioma: The emergence of genetic information. Neurosurgical Focus, 38(1), E6. https://doi.org/10.3171/2014.10.FOCUS12367

Post, M. (2014). Definitions of quality of life: What has happened and how to move on. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation, 20(3), 167–180. https://doi.org/10.1310/SCI2003-167

Khan, F., & Amatya, B. (2013). Factors associated with long-term functional outcomes, psychological sequelae and quality of life in persons after primary brain tumour. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 111(3), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-012-1024-z

Boele, F. W., Klein, M., Reijneveld, J. C., Verdonck-de Leeuw, I. M., & Heimans, J. J. (2014). Symptom management and quality of life in glioma patients. In CNS oncology Future Medicine Ltd London, UK. https://doi.org/10.2217/cns.13.65

Liu, R., Page, M., Solheim, K., Fox, S., & Chang, S. M. (2009). Quality of life in adults with brain tumors: Current knowledge and future directions. Neuro-Oncology, 11(3), 330–339. https://doi.org/10.1215/15228517-2008-093

Losing myself the reality of life with a brain tumour Contents. (n.d.)

Huang, M. E., Wartella, J., Kreutzer, J., Broaddus, W., & Lyckholm, L. (2001). Functional outcomes and quality of life in patients with brain tumours: A review of the literature. Brain Injury, 15(10), 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699050010013653

Aaronson, N. K., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Heimans, J. J., Postma, T. J., Gundy, C. M., Beute, G. N., Slotman, B. J., & Klein, M. (2011). Compromised health-related quality of life in patients with low-grade glioma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 29(33), 4430–4435. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.35.5750

Cheng, J. X., Liu, B., & lin, Zhang, X., Lin, W., Zhang, Y. qiang, Liu, W. ping, Zhang, J. N., Lin, H., Wang, R., & Yin, H. (2010). Health-related quality of life in glioma patients in China. BMC Cancer, 10(1), 305. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2407-10-305

Giovagnoli, A. R., Meneses, R. F., Silvani, A., Milanesi, I., Fariselli, L., Salmaggi, A., & Boiardi, A. (2014). Quality of life and brain tumors: What beyond the clinical burden? Journal of Neurology, 261(5), 894–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00415-014-7273-3

Farace, E., & Sheehan, J. (2014). QL-09 * Trajectory of quality of life at end of life in malignant glioma: Support for the terminal drop theory. Neuro-Oncology, 16(suppl 5), v180–v180. https://doi.org/10.1093/neuonc/nou269.9

Kennedy-Martin, T., Curtis, S., Faries, D., Robinson, S., & Johnston, J. (2015). (2015) A literature review on the representativeness of randomized controlled trial samples and implications for the external validity of trial results. Trials, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13063-015-1023-4

Jakola, A. S., Unsgård, G., Myrmel, K. S., Kloster, R., Torp, S. H., Sagberg, L. M., Lindal, S., & Solheim, O. (2014). Surgical strategies in low-grade gliomas and implications for long-term quality of life. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 21(8), 1304–1309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2013.11.027

Kiebert, G. M., Curran, D., Aaronson, N. K., Bolla, M., Menten, J., Rutten, E. H. J. M., Nordman, E., Silvestre, M. E., Pierart, M., & Karim, A. B. M. F. (1998). Quality of life after radiation therapy of cerebral low-grade gliomas of the adult: Results of a randomised phase III trial on dose response (EORTC trial 22844). European Journal of Cancer, 34(12), 1902–1909. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-8049(98)00268-8

Taphoorn, M. J. B., Van Den Bent, M. J., Mauer, M. E. L., Coens, C., Delattre, J. Y., Brandes, A. A., Sillevis Smitt, P. A. E., Bernsen, H. J. J. A., Frénay, M., Tijssen, C. C., Lacombe, D., Allgeier, A., & Bottomley, A. (2007). Health-related quality of life in patients treated for anaplastic oligodendroglioma with adjuvant chemotherapy: Results of a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer randomized clinical trial. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25(36), 5723–5730. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2007.12.7514

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., & Brennan, S. E. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, 23.

Bottomley, A. (2002). The cancer patient and quality of life; The cancer patient and quality of life. The Oncologist, 7, 120–125. https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.7-2-120

Louis, D. N., Perry, A., Reifenberger, G., von Deimling, A., Figarella-Branger, D., Cavenee, W. K., Ohgaki, H., Wiestler, O. D., Kleihues, P., & Ellison, D. W. (2016). The 2016 world health organization classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. In Acta Neuropathologica, 131(6), 803–820. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1

Louis, D. N., Perry, A., Wesseling, P., Brat, D. J., Cree, I. A., Figarella-Branger, D., Hawkins, C., Ng, H. K., Pfister, S. M., Reifenberger, G., Soffietti, R., von Deimling, A., & Ellison, D. W. (2021). The 2021 WHO classification of tumors of the central nervous system: A summary. Neuro-Oncology, 23(8), 1231–1251. https://doi.org/10.1093/NEUONC/NOAB106

Taphoorn, M. J. B. (2013). Quality of life in low-grade gliomas. Cham: In Diffuse Low-Grade Gliomas in Adults Springer.

Dunne, S., Mooney, O., Coffey, L., Sharp, L., Desmond, D., Timon, C., O’Sullivan, E., & Gallagher, P. (2017). Psychological variables associated with quality of life following primary treatment for head and neck cancer: A systematic review of the literature from 2004 to 2015. Psycho-Oncology, 26(2), 149–160. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4109

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1, b92.

Scott, N. W., Fayers, P., Aaronson, N. K., Bottomley, A., de Graeff, A., Groenvold, M., Gundy, C., Koller, M., Petersen, M. A., & Sprangers, M. A. G. (2008). EORTC QLQ-C30 reference values manual

Janssen, B., & Szende, A. (2014). Population norms for the EQ-5D. Self-Reported Population Health: An International Perspective Based on EQ-5D, 19–30

Holzner, B., Kemmler, G., Cella, D., de Paoli, C., Meraner, V., Kopp, M., Greil, R., Fleischhacker, W. W., & Sperner-Unterweger, B. (2004). Normative data for functional assessment of cancer therapy general scale and its use for the interpretation of quality of life scores in cancer survivors. Acta Oncologica, 43(2), 153–160.

Boele, F. W., Zant, M., Heine, E. C. E., Aaronson, N. K., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Reijneveld, J. C., Postma, T. J., Heimans, J. J., & Klein, M. (2014). The association between cognitive functioning and health-related quality of life in low-grade glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology Practice, 1(2), 40–46. https://doi.org/10.1093/nop/npu007

Boele, F. W., Douw, L., Reijneveld, J. C., Robben, R., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Aaronson, N. K., Heimans, J. J., & Klein, M. (2015). Health-related quality of life in stable. Long-Term Survivors of Low-Grade Glioma. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2014.56.9079

Ediebah, D. E., Reijneveld, J. C., & Martin, •, Taphoorn, J. B., Coens, • Corneel, Zikos, E., Aaronson, N. K., Heimans, J. J., Bottomley, • Andrew, & Klein, • Martin. (2016). Impact of neurocognitive deficits on patient-proxy agreement regarding health-related quality of life in low-grade glioma patients on behalf of the EORTC. Quality of Life Department and Patient Reported Outcome and Behavioral Evidence (PROBE). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1426-z

Affronti, M. L., Randazzo, D., Lipp, E. S., Peters, K. B., Herndon, S. C., Woodring, S., Healy, P., Cone, C. K., Herndon, J. E., & Schneider, S. M. (2018). Pilot study to describe the trajectory of symptoms and adaptive strategies of adults living with low-grade glioma. Seminars in Oncology Nursing, 34(5), 472–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soncn.2018.10.006

Budrukkar, A., Jalali, R., Dutta, D., Sarin, R., Devlekar, R., Parab, S., & Kakde, A. (2009). Prospective assessment of quality of life in adult patients with primary brain tumors in routine neurooncology practice. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 95(3), 413–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-009-9939-8

Campanella, F., Palese, A., Del Missier, F., Moreale, R., Ius, T., Shallice, T., Fabbro, F., & Skrap, M. (2017). Long-term cognitive functioning and psychological well-being in surgically treated patients with low-grade glioma. World Neurosurgery, 103, 799-808.e9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.WNEU.2017.04.006

Correa, D. D., DeAngelis, L. M., Shi, W., Thaler, H. T., Lin, M., & Abrey, L. E. (2007). Cognitive functions in low-grade gliomas: Disease and treatment effects. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 81(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-006-9212-3

Correa, D. D., Shi, W., Thaler, H. T., Cheung, A. M., DeAngelis, L. M., & Abrey, L. E. (2008). Longitudinal cognitive follow-up in low grade gliomas. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 86(3), 321–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-007-9474-4

Drewes, C., Sagberg, L. M., Jakola, A. S., & Solheim, O. (2018). Perioperative and postoperative quality of life in patients with glioma–a longitudinal cohort study. World Neurosurgery, 117, e465–e474. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2018.06.052

Gabel, N., Altshuler, D. B., Brezzell, A., Briceño, E. M., Boileau, N. R., Miklja, Z., Kluin, K., Ferguson, T., McMurray, K., Wang, L., Smith, S. R., Carlozzi, N. E., & Hervey-Jumper, S. L. (2019). Health related quality of life in adult low and high-grade glioma patients using the national institutes of health patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) and Neuro-QOL assessments. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 212. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2019.00212

Gustafsson, M., Edvardsson, T., & Ahlström, G. (2006). The relationship between function, quality of life and coping in patients with low-grade gliomas. Supportive Care in Cancer, 14(12), 1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-006-0080-3

Jakola, A. S., Unsgård, G., Myrmel, K. S., Kloster, R., Torp, S. H., Lindal, S., & Solheim, O. (2012). Low grade gliomas in eloquent locations – implications for surgical strategy, survival and long term quality of life. PLoS ONE, 7(12), e51450. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0051450

Jiang, C., & Wang, J. (2019). Post-traumatic stress disorders in patients with low-grade glioma and its association with survival. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 142(2), 385–392. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-019-03112-3

Kim, S. R., Kim, H. Y., Nho, J. H., Ko, E., Moon, K. S., & Jung, T. Y. (2020). Relationship among symptoms, resilience, post-traumatic growth, and quality of life in patients with glioma. European Journal of Oncology Nursing, 48, 101830. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2020.101830

Klein, M., Engelberts, N. H. J., van der Ploeg, H. M., Kasteleijn-Nolst Trenité, D. G. A., Aaronson, N. K., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Baaijen, H., Vandertop, W. P., Muller, M., Postma, T. J., & Heimans, J. J. (2003). Epilepsy in low-grade gliomas: The impact on cognitive function and quality of life. Annals of Neurology, 54(4), 514–520. https://doi.org/10.1002/ana.10712

Leonetti, A., Puglisi, G., Rossi, M., Viganò, L., Nibali, M. C., Gay, L., Sciortino, T., Howells, H., Fornia, L., Riva, M., Cerri, G., & Bello, L. (2021). Factors influencing mood disorders and health related quality of life in adults with glioma: A longitudinal study. Frontiers in Oncology. https://doi.org/10.3389/FONC.2021.662039

Mahalakshmi, P., & Vanisree, A. (2015). Quality of life measures in glioma patients with different grades: A preliminary study. Indian Journal of Cancer, 52(4), 580. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-509X.178395

Okita, Y., Narita, Y., Miyahara, R., Miyakita, Y., Ohno, M., & Shibui, S. (2015). Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors with Grade II gliomas: The contribution of disease recurrence and Karnofsky Performance Status. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 45(10), 906–913. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyv115

Reijneveld, J. C., Sitskoorn, M. M., Klein, M., Nuyen, J., & Taphoorn, M. J. B. (2001). Cognitive status and quality of life in patients with suspected versus proven low-grade gliomas. Neurology, 56(5), 618–623. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.56.5.618

Ruge, M. I., Ilmberger, J., Tonn, J. C., & Kreth, F. W. (2011). Health-related quality of life and cognitive functioning in adult patients with supratentorial WHO grade II glioma: Status prior to therapy. Journal of Neuro-Oncology, 103(1), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11060-010-0364-9

Salo, J., Niemelä, A., Joukamaa, M., & Koivukangas, J. (2002). Effect of brain tumour laterality on patients’ perceived quality of life. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 72(3), 373–377. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.3.373

Mainio, A., Tuunanen, S., Hakko, H., Niemelä, A., Koivukangas, J., & Räsänen, P. (2006). Decreased quality of life and depression as predictors for shorter survival among patients with low-grade gliomas: A follow-up from 1990 to 2003. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 256(8), 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-006-0674-2

Teng, K. X., Price, B., Joshi, S., Alukaidey, L., Shehab, A., Mansour, K., Toor, G. S., Angliss, R., & Drummond, K. (2021). Life after surgical resection of a low-grade glioma: A prospective cross-sectional study evaluating health-related quality of life. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience, 88, 259–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jocn.2021.03.038

Umezaki, S., Shinoda, Y., Mukasa, A., Tanaka, S., Takayanagi, S., Oka, H., Tagawa, H., Haga, N., & Yoshino, M. (2020). Factors associated with health-related quality of life in patients with glioma: Impact of symptoms and implications for rehabilitation. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 50(9), 990–998. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyaa068

Wang, X., Li, J., Chen, J., Fan, S., Chen, W., Liu, F., Chen, D., & Hu, X. (2018). Health-related quality of life and posttraumatic growth in low-grade gliomas in China: A prospective study. World Neurosurgery, 111, e24–e31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wneu.2017.11.122

Li, J., Wang, X., Wang, C., & Sun, L. (2019). The moderating role of depression on the association between posttraumatic growth and health-related quality of life in low-grade glioma patients in China. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 24(6), 643–653. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2018.1557714

Li, J., Sun, L., Wang, X., Sun, C., Heng, S., Hu, X., Chen, W., & Liu, F. (2019). Are Posttraumatic stress symptoms and avoidant coping inhibitory factors? The association between posttraumatic growth and quality of life among low-grade gliomas patients in China. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00330

Yavas, C., Zorlu, F., Ozyigit, G., Gurkaynak, M., Yavas, G., Yuce, D., Cengiz, M., Yildiz, F., & Akyol, F. (2012). Prospective assessment of health-related quality of life in patients with low-grade glioma A single-center experience. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(8), 1859–1868. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-011-1288-4

Dirven, L., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Musoro, J. Z., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Coens, C., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Reijneveld, J. C., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Taphoorn, M. J. B., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Boele, F. W., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Groenvold, M., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., van den Bent, M. J., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Stupp, R., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L., Velikova, G., Groups, on behalf of the E. B. T. G. and Q. of L. (2021). Establishing anchor-based minimally important differences for the EORTC QLQ-C30 in glioma patients. Neuro-Oncology, 23(8), 1327–1336. https://doi.org/10.1093/NEUONC/NOAB037

Fountain, D. M., Allen, D., Joannides, A. J., Nandi, D., Santarius, T., & Chari, A. (2016). Reporting of patient-reported health-related quality of life in adults with diffuse low-grade glioma: A systematic review. Neuro-Oncology, 18(11), 1475–1486. https://doi.org/10.1093/NEUONC/NOW107

Secinti, E., Tometich, D. B., Johns, S. A., & Mosher, C. E. (2019). The relationship between acceptance of cancer and distress: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 71, 27–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPR.2019.05.001

Hilari, K., Owen, S., & Farrelly, S. J. (2007). Proxy and self-report agreement on the stroke and aphasia quality of life scale-39. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 78(10), 1072–1075. https://doi.org/10.1136/JNNP.2006.111476

Goodglass, H., Kaplan, E., & Barresi, B. (2001). The assessment of aphasia and related disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Cockrell, J. R., & Folstein, M. F. (2002). Mini-mental state examination. Principles and Practice of Geriatric Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1002/0470846410.ch27(ii)

Taphoorn, M. J. B., Claassens, L., Aaronson, N. K., Coens, C., Mauer, M., Osoba, D., Stupp, R., Mirimanoff, R. O., van den Bent, M. J., & Bottomley, A. (2010). An international validation study of the EORTC brain cancer module (EORTC QLQ-BN20) for assessing health-related quality of life and symptoms in brain cancer patients. European Journal of Cancer, 46(6), 1033–1040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2010.01.012

Brownsett, S. L. E., Ramajoo, K., Copland, D., McMahon, K. L., Robinson, G., Drummond, K., Jeffree, R. L., Olson, S., Ong, B., & Zubicaray, G. D. (2019). Language deficits following dominant hemisphere tumour resection are significantly underestimated by syndrome-based aphasia assessments. Aphasiology, 33(10), 1163–1181. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2019.1614760

Simmons-Mackie, N., Kagan, A., Charles Victor, J., Carling-Rowland, A., Mok, A., Hoch, J. S., Huijbregts, M., & Streiner, D. L. (2014). The assessment for living with aphasia: Reliability and construct validity. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 16(1), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.3109/17549507.2013.831484

Andrewes, H. E., Drummond, K. J., Rosenthal, M., Bucknill, A., & Andrewes, D. G. (2013). Awareness of psychological and relationship problems amongst brain tumour patients and its association with carer distress. Psycho-Oncology, 22(10), 2200–2205. https://doi.org/10.1002/PON.3274

Khan, F., & Amatya, B. (2013). Use of the international Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) to describe patient -reported disability in primary brain tumour in an Australian comunity cohort. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 45(5), 434–445. https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-1132

Edvardsson, T., & Ahlström, G. (2005). Illness-related problems and coping among persons with low-grade glioma. Psycho-Oncology, 14(9), 728–737. https://doi.org/10.1002/PON.898

Acknowledgements

We thank Bogdan Metes for his assistance with the search strategy, and Tracy Finch for her contribution to the Ways Ahead project, from which this review is an output (research.ncl.ac.uk/waysahead).

Funding

This review was supported by funding from The Brain Tumour Charity (GN-000435).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Securing the funding: LS, JL, SW, PG, RB, VA-S Conceptualising the review: B.R, I.B, L.D and L.S. Conducting the searches: BR and IB Search screening: B.R and I.B. Data extraction, analysis, and interpretation: B.R and I.B. Drafting the manuscript: B.R. Review, revision, and approval of the final manuscript: BR, IB, LD, JL, RB, PG, SW, VA-S, FM, LS.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rimmer, B., Bolnykh, I., Dutton, L. et al. Health-related quality of life in adults with low-grade gliomas: a systematic review. Qual Life Res 32, 625–651 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03207-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-022-03207-x