Abstract

Background: A large proportion of the Canadian population lives a sedentary lifestyle. Few data are available describing the physical activity behaviours among specific ethnic groups in Canada, so the purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between ethnicity and the level of self-reported physical activity.

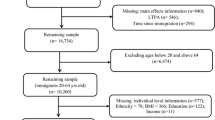

Methods: Pooled data from cycles 1.1 (2000/01) and 2.1 (2003) of the cross-sectional Canadian Community Health Survey (ages 20–64 yrs; N=171,513) were used for this study. Weighted prevalences of self-reported leisure-time moderate (≥1.5 kcal·kg−1·day−1 (kkd)); moderate to high (≥3 kkd) and high physical activity (≥6 kkd) were calculated, and multiple logistic regression models were used to quantify the odds of being physically active across ethnic groups, after adjustment for several covariates (White referent group).

Results: The rank order of prevalence of being moderately physically active by ethnicity was: White (49%), Other (48%), NA Aboriginal (47%), Latin American (40%), East/Southeast Asian (39%), Black (38%), West Asian/Arab (36%), South Asian (34%). Aboriginal men and women had the highest prevalences of being physically active at ≥3 kkd (M=32%, F=22%) while East/Southeast Asian (19%) and East Asian/Arab men (19%), and South Asian women (12%) had the lowest prevalences. After accounting for covariates, Aboriginal men were at elevated odds of being physically active compared to Whites (≥3 kkd, OR=1.6, p<0.05; ≥6 kkd, OR=2.7, p<0.05). Only 7% and 3% of Canadian men and women, respectively, were active at ≥6 kkd.

Conclusion: These results suggest that the prevalence of physically active Canadian adults varies by ethnicity. Strategies to promote physical activity and prevent physical inactivity should consider these findings.

Résumé

Contexte: Une proportion importante de la population canadienne a un mode de vie sédentaire. Il existe peu de données décrivant les comportements en matière d’activité physique de certains groupes ethniques au Canada. Cette étude vise donc à examiner le rapport entre l’origine ethnique et le niveau d’activité physique autodéclaré.

Méthode: Pour cette étude, nous avons utilisé des données regroupées des cycles 1.1 (2000–2001) et 2.1 (2003) de l’Enquête transversale sur la santé dans les collectivités canadiennes (personnes âgées de 20 à 64 ans; N=171 513). Des prévalences pondérées de l’activité physique autodéclarée durant les loisirs (modérée [≥1,5 kcal·kg−1·jour−1 (KKJ)], modérée à élevée [≥3 KKJ] et élevée [≥6 KKJ]) ont été calculées, et des modèles de régression logistique multiple ont servi à quantifier la cote exprimant la probabilité d’être physiquement actif selon le groupe ethnique, après rajustement selon plusieurs covariables (le groupe de référence était de race blanche).

Résultats: L’ordre de classement de la prévalence de l’activité physique modérée selon l’origine ethnique était le suivant: Blancs (49 %), Autres (48 %), Autochtones de l’Amérique du Nord (47 %), Latino-Américains (40 %), Asiatiques de l’Est/du Sud Est (39 %), Noirs (38 %), Asiatiques de l’Ouest/Arabes (36 %), Asiatiques du Sud (34 %). Les hommes et les femmes autochtones avaient la prévalence la plus forte d’être physiquement actifs, à ≥3 KKJ (H=32 %, F=22 %), tandis que les hommes originaires de l’Asie de l’Est/du Sud Est (19 %), de l’Asie de l’Est et des pays arabes (19 %), de même que les femmes de l’Asie du Sud (12 %), avaient la prévalence la plus faible. Une fois prises en compte les covariables, les hommes autochtones obtenaient une cote exprimant la probabilité d’être physiquement actifs élevée comparativement aux Blancs (≥3 KKJ, RC=1,6, p<0,05; ≥6 KKJ, RC=2,7, p<0,05). Seulement 7 % et 3 % des Canadiens et Canadiennes, respectivement, avaient un niveau d’activité supérieur ou égal à 6 KKJ.

Conclusion: Ces résultats montrent que la prévalence de l’activité physique chez les adultes canadiens varie selon l’origine ethnique. Les stratégies visant à promouvoir l’activité physique et à prévenir la sédentarité devraient donc en tenir compte.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

US Department of Health and Human Services. Physical Activity and Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1996.

Bruce MJ, Katzmarzyk PT. Canadian population trends in leisure-time physical activity levels, 1981–1998. Can J Appl Physiol 2002;27:681–90.

Craig CL, Russell SJ, Cameron C, Bauman A. Twenty-year trends in physical activity among Canadian adults. Can J Public Health 2004;95(1):59–63.

Statistics Canada. Health Indicators. 2002. Ottawa, ON, Catalogue No. 82-221-XIE.

Katzmarzyk PT, Janssen I. The economic costs associated with physical inactivity and obesity in Canada: An update. Can J Appl Physiol 2004;29:90–115.

Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers. Annual Meeting of the Federal and Provincial/Territorial Ministers of Sport, Recreation and Fitness - Feb. 21–22, 2003. Bathhurst, New Brunswick. Available online at: http://www.scics.gc.ca/cinfo03/830778004_e.html (Accessed January 20, 2005).

Bryan S, Walsh P. Physical activity and obesity in Canadian women. BMC Women’s Health 2004;4:S1–S6.

Craig CL, Brownson RC, Cragg SE, Dunn AL. Exploring the effect of the environment on physical activity. A study examining walking to work. Am J Prev Med 2002;23:36–43.

Béland Y. Canadian Community Health Survey-Methodological overview. Health Rep 2002;13:9–14.

Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: An update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:S498–S516.

Health Canada. Canadian guidelines for body weight classification. 2003. Ottawa, ON. Available online at: http://www.healthcanada.ca/nutrition (Accessed January 20, 2005).

Pérez CE. Health status and health behaviour among immigrants. Health Rep 2002;13:89–45.

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey,(CCHS) Cycle 1.1. Derived Variable (DV) Specifications. 2002. Available online at: http://www.statcan.ca/english/D1./Data/ftp/cchs/cchs.htm (Accessed January 20, 2005).

Rao JNK, Wu CFJ, Yue K. Some recent work on resampling methods for complex surveys. Survey Methodol 1992;18:209–17.

Rust K, Rao JNK. Variance estimation for complex surveys using replication techniques. Stat Methods Med Res 1996;5:281–310.

Yeo D, Mantel H, Liu TP. Bootstrap variance estimation for the National Population Health Survey. American Statistical Association: Proceedings of the Survey Research Methods Section Conference, 1999.

Crespo CJ, Smit E, Andersen RE, Carter-Pokras O. Race/ethnicity, social class and their relation to physical inactivity during leisure time: Results from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. Am J Prev Med 2000;18:46–53.

Ham SA, Yore MM, Fulton JE, Kohl III HW. Prevalence of no leisure-time physical activity-35 states and the District of Columbia, 1988–2002. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53:82–86.

Tremblay MS, Pérez CE, Ardern CI, Bryan SN, Katzmarzyk PT. Obesity, overweight and ethnicity. Health Reps 2005;16(4):23–34.

Fischbacher CM, Hunt S, Alexander L. How physically active are South Asians in the United Kingdom? A literature review. J Public Health (Oxf) 2004;26:250–58.

Warnecke RB, Johnson TP, Chávez N, Sudman S, O’Rourke DP, Lacey L, Horm J. Improving question wording in surveys of culturally diverse populations. Ann Epidemiol 1997;7:334–42.

Tortolero SR, Mâsse LC, Fulton JE, Torres I. Assessing physical activity among minority women: Focus group results. Women’s Health Issues 1999;9:135–42.

Sallis JF, Saelens BE. Assessment of physical activity by self-report: Status, limitations and future directions. Res Quart Exerc Sport 2000;59:314–27.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of leisure-time and occupational physical activity among employed adults - United States, 1990. MMWR 2004;49:420–24.

Comstock RD, Castillo EM, Lindsay SP. Fouryear review of the use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic and public health research. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:611–19.

Hahn RA, Truman BI, Barker ND. Identifying ancestry: The reliability of ancesteral identification in the United States by self, proxy, interviewer, and funeral director. Epidemiol 1996;7:75–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bryan, S.N., Tremblay, M.S., Pérez, C.E. et al. Physical Activity and Ethnicity. Can J Public Health 97, 271–276 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405602

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405602