Abstract

Context

Obesity is a major public health problem in North America, particularly in Aboriginal people.

Objective

To determine if a household-based lifestyle intervention is effective at reducing energy intake and increasing physical activity among Aboriginal families after 6 months.

Design, Participants, and Intervention

Randomized, open trial of 57 Aboriginal households recruited between May 2004 and April 2005 from the Six Nations Reserve in Ohsweken, Canada. Aboriginal Health Counsellors made regular home visits to assist families in setting dietary and physical activity goals. Additional interventions included provision of filtered water, a physical activity program for children, and educational events about healthy lifestyles.

Results

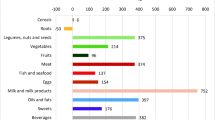

57 households involving 174 individuals were randomized to intervention or usual care. Intervention households decreased consumption of fats, oils and sweets compared to usual care households (-4.9 servings per day vs. -3 servings/day, p=0.006), and this was associated with a reduction in trans fatty acids (-0.2 vs. +0.6 grams/day, p=0.02). Water consumption increased (+0.3 vs. -0.1 servings/day, p<0.04) and soda pop consumption decreased (-0.3 vs. -0.1 servings/day, p=0.02) in intervention households compared to usual care. A trend toward increased knowledge about healthy dietary practices in children, increased leisure-time activity and decreased sedentary behaviours was observed, although these differences were not statistically significant.

Conclusion

A household-based intervention is associated with some positive changes in dietary practices and activity patterns. A larger and longer-term intervention which addresses both individual change and structural barriers in the community is needed.

Résumé

Contexte

L’obésité est un problème de santé publique majeur en Amérique du Nord, particulièrement chez les Autochtones.

Objectif

Déterminer si une intervention de modification du mode de vie centrée sur les ménages parvient à réduire l’apport énergétique et à accroître l’activité physique dans des familles autochtones au bout de six mois.

Méthode, participants et intervention

Essai ouvert aléatoire auprès de 57 ménages autochtones recrutés entre mai 2004 et avril 2005 dans la réserve des Six-Nations à Ohsweken (Ontario), au Canada. Des conseillers en santé autochtone ont fait des visites à domicile périodiques pour aider les familles à se fixer des objectifs de saine alimentation et d’activité physique. D’autres mesures ont aussi été instaurées: on a fourni de l’eau filtrée aux ménages, offert un programme d’activité physique aux enfants et organisé des activités de sensibilisation aux modes de vie sains.

Résultats

Les 57 ménages (174 personnes) ont été répartis aléatoirement en deux groupes, l’un recevant les mesures d’intervention et l’autre, les soins habituels. Les ménages recevant les mesures d’intervention ont diminué leur consommation de matières grasses, d’huile et de sucreries par rapport aux ménages recevant les soins habituels (-4,9 portions/jour contre -3 portions/jour, p=0,006), et cette diminution était associée à une baisse de la consommation d’acides gras trans (-0,2 contre +0,6 g/jour, p=0,02). Par ailleurs, leur consommation d’eau a augmenté (+0,3 contre -0,1 portion/jour, p<0,04), et leur consommation de boissons gazeuses a diminué (-0,3 contre -0,1 portion/jour, p=0,02). Nous avons aussi observé une amélioration des connaissances des enfants sur la saine alimentation, une augmentation de l’activité pendant les temps libres et une diminution des comportements sédentaires, mais ces changements n’étaient pas significatifs.

Conclusion

Une intervention centrée sur les ménages est associée à certains changements positifs dans l’alimentation et l’activité physique. Il faudrait élargir et prolonger l’initiative, en tenant compte à la fois des changements individuels et des obstacles structurels dans la communauté.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mokdad AH, Bowman BA, Ford ES, Vinicor F, Marks JS, Koplan, JP. The continuing epidemics of obesity and diabetes in the United States. JAMA 2001; 12; 286(10):1195–200.

Yach D, Stuckler D, Brownell KD. Epidemiologic and economic consequences of the global epidemics of obesity and diabetes. Nat Med 2006; 12(1):62–66.

Harris SB, Gittelsohn J, Hanley A, Barnie A, Wolever TM, Gao J, et al. The prevalence of NIDDM and associated risk factors in native Canadians. Diabetes Care 1997; 20(2):185–87.

Anand SS, Yusuf S, Jacobs R, Davis AD, Yi Q, Gerstein H, et al. Risk factors, atherosclerosis, and cardiovascular disease among Aboriginal people in Canada: The Study of Health Assessment and Risk Evaluation in Aboriginal Peoples (SHARE-AP). Lancet 2001; 358(9288):1147–53.

Six Nation Community. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.sixnations.ca/Profile.htm (Accessed January 15, 2006).

Caballero B, Clay T, Davis SM, Ethelbah B, Rock BH, Lohman T, et al. and Pathways Study Research Group. Pathways: A school-based, Randomized controlled trial for the prevention of obesity in American Indian schoolchildren. Am J Clin Nutr 2003; 78(5):1030–38.

Jeffery, RW. Public health strategies for obesity treatment and prevention. Am J Health Behav 2001; 25(3):252–59.

Carleton RA, Lasater TA, Assaf AR, Feldman HA, McKinlay S, and the Pawtucket Heart Health Program Writing Group. The Pawtucket Heart Health Program: Community changes in cardiovascular risk factors and projected disease risk. Am J Public Health 1995; 85(6):777–85.

French SA, Story M, Jeffery, RW. Environmental influences on eating and physical activity. Annu Rev Public Health 2001; 20:309–35.

Shaw K, O’Rourke P, Del Mar C, Kenardy J. Psychological interventions for overweight or obesity. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; 18(2):CD003818.

SHARE-AP ACTION Study. https://doi.org/www.phri.ca/SHARE-APACTION.

Elder JP, Ayala GX, Harris S. Theories and intervention approaches to health-behavior change in primary care. Am J Prev Med 1999; 17(4):275–84.

Maddux JE, Rogers, RW. Protection motivation and self-efficacy. A revised theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Exp Soc Psychol 1983; 19:469–79.

Parcel, GS. Social learning theory and health education. Health Educ 1981; 12(3):14–18.

Perry CL, Baranowski T, Parcel G. How individuals, environments, and health behavior interact: Social learning theory. In: Glantz K, Lewis FM, Rimer B (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1990; 161–86.

Canada Food Guide to Healthy Eating. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/nutrition/pube/foodguid/index.html (Accessed January 15, 2004).

Canada Healthy Active Living–Consult Canada’s Physical Activity Guide to Healthy Active Living to help build physical activity into your daily life. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hppb/paguide/ (Accessed January 15, 2004).

Weber JL, Lytle L, Gittelsohn J, Cunningham-Sabo L, Heller K, Anliker JA, et al. Validity of self-reported dietary intake at school meals by American Indian children: The Pathways Study. J Am Diet Assoc 2004; 104(5):746–52.

ESHA Website. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.esha.com/ Nutrition Analysis Software and databases (Accessed January 15, 2006).

International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Available online at: https://doi.org/www.ipaq.ki.se/ (Accessed January 15, 2006).

Going SB, Levin S, Harrell J, Stewart D, Kushi L, Cornell CE, et al. Physical activity assessment in American Indian schoolchildren in the Pathways Study. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69(Suppl):788S–795S.

Stevens J, Cornell CE, Story M, French SA, Levin S, Becenti A, et al. Development of a questionnaire to assess knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors in American Indian children. Am J Clin Nutr 1999; 69(4 Suppl):773S–781S. Pathways KAB.

Hsieh, FY. Sample size formulae for intervention studies with the cluster as unit of randomization. Stat Med 1988; 8:1195–201.

Rychetnik L, Frommer M, Hawe P, Shiell A. Criteria for evaluating evidence on public health interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health 2002; 56(2):119–27.

Nader PR, Sallis JF, Patterson TL, Abramson IS, Rupp JW, Senn KL, et al. A family approach to cardiovascular risk reduction: Results from the San Diego Family Health Project. Health Educ Q 1989; 16(2):229–44.

Frank LD, Andresen MA, Schmid, TL. Obesity relationships with community design, Physical activity, and time spent in cars. Am J Prev Med 2004; 27(2):87–96.

Anand SS, Razak F, Davis AD, Jacobs R, Vuksan V, Teo K, et al. Social disadvantage and cardiovascular disease: Development of an index and analysis of age, Sex, and ethnicity effects. Int J Epidemiol 2006; 35(5):1239–45. Epub 2006

Glanz K, Hoelscher D. Increasing fruit and vegetable intake by changing environments, Policy and pricing: Restaurant-based research, Strategies, and recommendations. Prev Med 2004; 39(Suppl 2):S88–S93.

Paradis G, Levesque L, Macaulay AC, Cargo M, McComber A, Kirby R, et al. Impact of a diabetes prevention program on body size, Physical activity, and diet among Kanien’keha:ka (Mohawk) children 6 to 11 years old: 8-year results from the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. Pediatrics 2005; 115(2):333–39.

Hebert JR, Ebbeling CB, Matthews CE, Hurley TG, Ma Y, Druker S, Clemow L. Systematic errors in middle-aged women’s estimates of energy intake: Comparing three self-report measures to total energy expenditure from doubly labeled water. Ann Epidemiol 2002; 12(8):577–86.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Additional information

Funding: Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Grant number: MCT 64076.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Anand, S.S., Davis, A.D., Ahmed, R. et al. A Family-based Intervention to Promote Healthy Lifestyles in an Aboriginal Community in Canada. Can J Public Health 98, 447–452 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405436

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03405436