Abstract

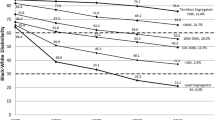

Data from fair housing audits conducted in Cincinnati (1983–85) and Memphis (1985–87) are analyzed to discern whether and how racial steering occurs. The six real estate firms analyzed here engaged in some sort of steering during at least one-half of the audited transactions, on average. This steering did not limit the number of alternative areas shown to black auditors, nor their geographic concentration. Rarely were black auditors not shown dwellings in predominantly white areas, especially if they requested such. But of all the homes they saw, black auditors were shown significantly smaller fractions in predominantly white areas, and significantly larger fractions in mixed and predominantly black areas. These racial patterns persisted regardless of the geographic definition of area chosen: census block, census tract, school district, or community. In addition, blocks adjacent to the homes shown black auditors had higher percentages of black residents, on average, than those shown to white auditors. White auditors rarely were shown houses in racially mixed areas unless they requested them. Even then, after the requested home was shown the bulk of subsequent showings were located in predominantly white areas. This pattern of showings was buttressed by numerous favorable comments by agents about such predominantly white areas and school districts . . . comments that were rarely given to black auditors. The evidence was fully consistent with only one hypothesis about why real estate agents steer. They steer so as to perpetuate two segregated housing markets buffered by a zone of racially transitional neighborhoods, thereby maximizing housing turnover and agents’ commissions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Cleveland Area Board of REALTORS, “Monthly Newsletter” (May, 1983).

This federal prohibition has recently been reaffirmed in the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988; see: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (1988) “Implementation of the Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988.” Federal Register 54, no. 13 (Jan. 23), pp. 3232-3317.

Rose Helper,Racial Policies and Practices of Real Estate Brokers (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1969); Diana Pearce, “Gatekeepers and Homeseekers: Institutional Patterns in Racial Steering,”Social Problems, Volume 26 (1979), pp. 325-342.

Judith Feins and Rachel Bratt, “Barred in Boston: Racial Discrimination in Housing,”Journal of American Planning Association, Volume 49 (Summer 1983), pp. 344–355.

Some observers have concluded that steering and other illegal real estate practices are no longer an important influence shaping racial settlement patterns in U.S. metropolitan areas: Richard Muth, “The Causes of Housing Segregation,” pp. 3-13 in U.S. Commission on Civil Rights,Issues in Housing Discrimination (Washington, D.C.: US-GPO, 1986); W.A.V. Clark, “Residential Segregation in American Cities: A Review and Interpretation,”Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 5 (1986), pp. 95-127. This conclusion has sparked vigorous controversy; see George Galster, “Residential Segregation in American Cities: A Contrary Review,”Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 7 (1988a), pp. 93-112; W.A.V. Clark, “Understanding Residential Segregation in American Cities: Interpreting The Evidence,”Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 8 (1988), pp. 113-121; George Galster, “Residential Segregation in American Cities: A Further Response,”Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 8 (1989), pp. 181-192; W.A.V. Clark, “Residential Segregation in American Cities: Common Ground and Differences in Interpretation,”Population Research and Policy Review, Volume 8 (1989), pp. 193-197.

GeoTge Galster, “Racial Steering in Housing Markets: A Review of the Audit Evidence,”Review of Black Political Economy, Volume 18, No. 3 (1990), pp. 105–129.

For further discussions of audit methodology, see Ron Wienk, Clifford Reid, John Simonson and Fred Eggers,Measuring Racial Discrimination in American Housing Markets (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development/Policy Development and Research, 1979); John Yinger,Statistics For Fair Housing Audits (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development/Policy Development and Research, 1985); John Yinger, “Measuring Discrimination with Fair Housing Audits,”American Economic Review, Volume 76 (1986), pp. 881-893.

Gail Finkbeiner and Karla Irvine,Cincinnati Northern Suburban Housing Market Practices Survey (Cincinnati: Housing Opportunities Made Equal, Inc., 1984).

Yinger (1985).

For an alternative conceptual scheme for analyzing steering, see Harriett Newburger,The Nature and Extent of Racial Steering Practices in U.S. Housing Markets (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development Working Paper, December, 1981).

We consider here only those audits during whichboth teammates were shown at least one home. Thus, unlike Newburger (1981), the refusal to show minorities any homes is not considered a form of steering.

By contrast, Newburger (1981), uses only the second criterion for assessing whether an audit evidenced steering.

Newburger (1981); Wienk et al. (1979).

“Community” was defined as either suburban municipality of multi-tract “community areas” within the city of Cincinnati.

Yinger (1985, 1986).

By comparison, Newburger (1981) estimated a 20-24 percent incidence of steering nationwide based on 1097 audits conducted in 40 metropolitan areas in 1977 wherein both teammates were shown homes. The estimates are not strictly comparable because of differences in defining incidence, in number of metropolitan areas analyzed, and in the fact that firms were not randomly selected in the present analysis.

A caveat must be mentioned here: 1980 Census data may not be an accurate reflection of the racial composition of areas in 1983–85 in Cincinnati and 1985–87 in Memphis. Many racially mixed areas in 1980 may have become predominantly black by the middle of the decade, for instance.

Pearce (1979); Housing Opportunities Made Equal,Racial Steering by Racial Sales Agents in Metropolitan Richmond (Richmond, VA: HOPE, 1980).

These results are virtually identical to those obtained in the 1978–79 audits in Richmond, VA., Housing Opportunities Made Equal (1980); Pearce (1979).

William Schwab, “The Predictive Value of Three Ecological Models,”Urban Affairs Quarterly, Volume 23 (Dec. 1987), pp. 295–308.

All the showings in tract 215.05 occurred during one audit where no steering occurred, clearly. Even the blocks shown with this tract varied greatly by racial composition.

Helper (1969); Pearce (1979).

Yinger (1986).

The motivation was a finding in the caseU.S. v. Real Estate One, 433 F. Supp. 1140 (E.D. Michigan 1977).

Yinger (1986); George Galster, “The Ecology of Racial Discrimination in Housing,”Urban Affairs Quarterly, Volume 23 (Dec. 1987), pp. 84-107; Harriett Newburger, “Discrimination by a Profit-Maximizing Broker in Response to White Prejudice,”Journal of Urban Economics, Volume 26 (1989), pp. 1-19.

Newburger (1989).

Pearce (1979).

Susan Bertram, Anne Brady and Christine Klepper,An Audit of the Real Estate Sales and Rental Markets of Selected Southern Suburbs (Homewood, IL: South Suburban Housing Center, Audit Report #10, 1987).

Housing Opportunities Made Equal (1980).

Yinger (1986).

Evidence in Yinger (1986) and Newburger (1989) does not allow them to reject this “customer prejudice” hypothesis.

Note that a strategy of introducing thefirst black homeseekers into an erstwhile all-white area may not generate added turnover in and of itself if the percentage of blacks remains below the “tolerance threshold” of whites; see Richard Taub, Garth Taylor and Jan Dunham,Paths of Neighborhood Change (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984: ch. 7) and George Galster, “White Flight From Racially Mixed Neighborhoods,”Urban Studies, Volume 27 (1990), pp. 385-399. Reticence for introducing the first black would be compounded, of course, if “customer prejudice” were also operative. Clearly, the potential discriminator gains most by steering blacks to and whites from areas that already are racially mixed (perhaps as a result of the nondiscriminatory behavior of other agents in the market).

Yinger (1986); Galster (1987); George Galster and Mark Keeney. “Race, Residence, Discrimination, and Economic Opportunity,”Urban Affairs Quarterly, Volume 24 (1988), pp. 87-117.

Dorothy Hall, William Peterman and Judy Dwyer,Measuring Discrimination and Steering in Chicago’s South Suburbs (Chicago: Voorhees Center, University of Illinois-Chicago, Technical Report 1-83, 1983).

George Galster,Federal Fair Housing Policy in the 1980s: The Great Misapprehension (Cambridge, MA: MIT Center for Real Estate Development, Housing Policy Paper #5, 1988b).

Galster (1988b).

About this article

Cite this article

Galster, G. Racial steering by real estate agents: Mechanisms and motives. Rev Black Polit Econ 19, 39–63 (1990). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02899931

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02899931