Abstract

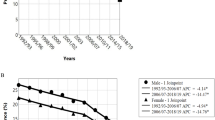

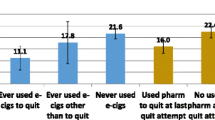

Objective: To determine which smokers report cigarette fading, how much they fade, when fading leads to quitting, and, if not, whether it can be maintained. Methods: Subjects were 1,682 adult smokers interviewed by telephone in 1990 and 1992 as part of the California Tobacco Survey. Data from three timepoints in the same subjects were compared. At Time 1 (one year before the baseline survey), all respondents were daily smokers who recalled their average daily cigarette consumption retrospectively at baseline. At Time 2 (baseline survey), all respondents were current smokers who provided concurrent data on their average daily cigarette consumption. At Time 3 (follow-up), smoking status and current cigarette consumption among nonabstinent respondents were assessed. Results: Nearly 18% of smokers reduced consumption between Times 1 and 2. The mean reduction was 13 cigarettes per day. Only moderate to heavy smokers who reduced consumption to below 15 cigarettes per day were more likely to be in cessation at Time 3 (24.9% versus 5.8%, respectively). The cessation rate for moderate to heavy smokers that became light smokers by baseline was similar to that for smokers who were already light smokers 1 year before baseline. Continuing smokers who reduced consumption between Times 1 and 2 maintained a mean reduction of 11.4 cigarettes per day. Conclusions: Cigarette fading increases cessation among moderate to heavy smokers who become light smokers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

McMorrow MJ, Foxx RM: Nicotine's role in smoking: An analysis of nicotine regulation.Psychological Bulletin. 1983,93:302–327.

Frederiksen LW, Martin JE, Webster JS: Assessment of smoking behavior.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979,12:653–664.

Sutton SR, Russell MAH, Iyer R, Feyerabend C, Salooyee Y: Relationship between cigarette yields, puffing patterns, and smoke intake. Evidence for tar compensation.British Medical Journal. 1982,285:600–603.

Ebert RV, McNabb E, McCusker K, Snow S: Amount of nicotine and carbon monoxide inhaled by smokers of low-tar, low-nicotine cigarettes.Journal of the American Medical Association. 1983,250:2840–2842.

Bridges RB, Combs JG, Humble JW, et al: Puffing topography as a determinant of smoke exposure.Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1990,37:29–39.

Djordjevic MV, Fan J, Ferguson S, Hoffman D: Self-regulation of smoking intensity. Smoke yields of the low-nicotine, low-‘tar’ cigarettes.Carcinogenesis. 1995,16:2015–2021.

Gori GB, Lynch CJ: Analytical cigarette yields as predictors of smoke bioavailability.Regulatory Toxicology and Pharmacology. 1985,5:314.

Benowitz NL, Jacob P: Daily intake of nicotine during cigarette smoking.Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1984,35:499–504.

Kolonen S, Tuomisto J, Puustinen P, Airaksinen MM: Effects of smoking abstinence and chain-smoking on puffing topography and diurnal nicotine exposure.Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1992,42:327–332.

U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare:Smoking and Health. A Report of the Surgeon Genera, 1979, DHEW Publication No. (PHS) 79-50066. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1979.

Frost C, Fullerton FM, Stephen AM, et al.: The tar reduction study: Randomized trial of the effect of cigarette tar yield reduction on compensatory smoking.Thorax. 1995,50:1038–1043.

Zacny JP, Stitzer ML: Cigarette brand-switching: Effects on smoke exposure and smoking behavior.Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1988,246:619–627.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services:The Health Consequences of Smoking: Nicotine Addiction. A Report of the Surgeon General, 1988 DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 88-8406. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1988.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services:Reducing the Health Consequences of Smoking: 25 Years of Progress. A Report of the Surgeon General, 1989, DHHS Publication No. (CDC) 89-8411. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1989.

McWhorter WP, Boyd GM, Mattson ME: Predictors of quitting smoking: The NHANES I follow-up experience.Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1990,43:1399–1405.

Freund KM, D Agostino RB, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB, Stokes J: Predictors of smoking cessation: The Framingham Study.American Journal of Epidemiology. 1992,135:957–964.

Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ: Prospective predictors of quit attempts and smoking cessation in young adults.Health Psychology. 1996,15:261–268.

Marlatt GA, Curry S, Gordon JR: A longitudinal analysis of unaided smoking cessation.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1988,56:715–720.

Cohen S, Lichtenstein E, Prochaska JO, et al: Debunking myths about self-quitting: Evidence from ten prospective studies of persons who attempt to quit by themselves.American Psychologist. 1989,44:1355–1365.

Farkas AJ, Pierce JP, Zhu S-H, et al: Addiction versus stages of change models in predicting smoking cessation.Addiction. 1996,91:1271–1280.

Levinson BL, Shapiro D, Schwartz GE, Tursky B: Smoking elimination by gradual reduction.Behavior Therapy. 1978,2:477–487.

Flaxman J: Quitting smoking now or later: Gradual, abrupt, immediate, and delayed quitting.Behavior Therapy. 1978,9:260–270.

Foxx RM, Brown RA: Nicotine fading and self-monitoring for cigarette abstinence or controlled smoking.Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1979,12:111–125.

Foxx RM, Brown RA, Katz I: Nicotine fading and self-monitoring for cigarette abstinence or controlled smoking: A two and one-half year follow-up.Behavior Therapist. 1981,4:21–23.

Beaver C, Brown RA, Lichtenstein E: Effects of monitored nicotine fading and anxiety management training on smoking reduction.Addictive Behaviors. 1981,6:301–305.

Foxx RM, Axelrod E: Nicotine fading, self-monitoring and cigarette to produce cigarette abstinence or controlled smoking.Behavior Therapist. 1983,21:17–27.

Prue DM, Davis CJ, Martin JE, Moss RA: An investigation of a minimal contact brand fading program for smoking treatment.Addictive Behaviors. 1983,8:307–310.

Brown RS, Lichtenstein E, McIntyre KO, Harrington-Kostur J: Effects of nicotine fading and relapse prevention on smoking cessation.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1984,52:307–308.

Lando HA, McGovern PG: Nicotine fading as a nonaversive alternative in a broad spectrum treatment for eliminating smoking.Addictive Behaviors. 1985,10:153–161.

Scott RR, Prue DM, Denier CA, King AC: Worksite smoking intervention with nursing professionals: Long-term outcome and relapse assessment.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1986,54:809–813.

Singh NN, Leung J-P: Smoking cessation through cigarette-fading, self-recording, and contracting: Treatment, maintenance and longterm follow-up.Addictive Behaviors. 1988,13:101–105.

Decker BD, Evans RG: Efficacy of a minimal contact version of a multimodal smoking cessation program.Addictive Behaviors. 1989,14:487–491.

McGovern PG, Lando HA: Reduced nicotine exposure and abstinence outcome in two nicotine fading methods.Addictive Behaviors. 1991,16:11–20.

Cinciripini PM, Lapitsky LG, Wallfish A, et al: An evaluation of a multicomponent treatment program involving scheduled smoking and relapse prevention procedures: Initial findings.Addictive Behaviors. 1994,19:13–22.

Cinciripini PM, Lapitsky L, Seay S, et al: The effects of smoking schedules on cessation outcome: Can we improve on common methods of gradual and abrupt nicotine withdrawal?.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995,63:388–399.

Russell MAH, Sutton SR, Feyerabend C, Saloojee Y: Smoker's response to shortened cigarettes: Dose reduction without dilution of tobacco smoke.Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1980.27:210–218.

Glasgow RE, Klesges RC, Vasey MW: Controlled smoking for chronic smokers: An extension and replication.Addictive Behaviors. 1983,8:143–150.

Sutton SR, Feyerabend C, Cole PV, Russell MAH: Adjustment of smokers to dilution of tobacco smoke by ventilated cigarette holders.Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1978,24:395–405.

Stitzer ML, Brigham J, Felch LJ: Phase-out filter perforation: Effects on human tobacco smoke exposure.Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 1992,41:749–754.

Waksberg J: Sampling methods of random digit dialing.Journal of the American Statistical Association. 1978,73:40–46.

Borland R, Pierce JP, Burns DM, et al: Protection from environmental tobacco smoke in California: The case for a smoke-free work-place.Journal of the American Medical Association. 1992,268(6): 749–752.

Pierce JP, Goodman J, Gilpin EA, Berry C:Technical Report on Analytic Methods and Approaches Used in the Tobacco Use in California, 1990–1991 Report. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 1992.

Pierce JP, Cavin SW, Macky C, et al:Technical Report on Analytic Methods and Approaches Used in the 1992 California Tobacco Survey Analysis. Sacramento, CA: California Department of Health Services, 1994.

Pierce JP, Evans N, Farkas AJ, et al:Tobacco Use in California. An Evaluation of the Tobacco Control Program, 1989–1993. La Jolla, CA: University of California, San Diego, 1994.

Rao JN, Scott AJ: On chi-squared tests for multiway contingency tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data.Archives of Statistics. 1984,12:46–60.

Westat, Inc.:A User's Guide to WesVarPC. Version 2.0. Rockville, MD: Westat, Inc., 1996.

Efron B:The Jackknife, the Bootstrap and Other Resampling Plans. CBMS Regional Conference Series in Applied Mathematics, 38. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics. 1982.

Pierce JP, Hatziandreu E, Flyer P, et al:Report of the 1986 Adult Use of Tobacco Survey. Atlanta, GA: Office of Smoking and Health, Centers for Disease Control, 1987.

Lichtenstein E, Glasgow RE: Smoking cessation: What have we learned over the past decade?Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1992,60:518–527.

Glasgow RE, Mullooly JP, Vogt TM: Biochemical validation of smoking status: Pros, cons, and data from four low-intensity intervention trials.Addictive Behaviors. 1993,18:511–527.

Glasgow RE, Klesges RC, Klesges LM, Vasey MW, Gunnarson DF: Long-term effects of a controlled smoking program: A 2-year follow-up.Behavior Therapy. 1985,16:303–307.

Jarvik ME, Schneider NG: Degree of addiction and effectiveness of nicotine gum therapy for smoking.American Journal of Psychiatry. 1984,141:790–791.

Niaura R, Goldstein MG, Abrams DB: Matching high-and low-dependence smokers to self-help treatment with or without nicotine replacement.Preventive Medicine. 1994,23:70–77.

Zhu S-H, Pierce JP: A new scheduling method for time-limited counseling.Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1995,26:624–625.

Zhu S-H, Stretch V, Balabanis M, et al: Telephone counseling for smoking cessation: Effects of single-session and multiple-session interventions.Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1995.64:202–211.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

About this article

Cite this article

Farkas, A.J. When does cigarette fading increase the likelihood of future cessation?. ann. behav. med. 21, 71–76 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02895036

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02895036