Abstract

In moist temperate and tropical environments species that typically become established in closed, shaded habitats tend to have larger seeds than those that regenerate in open, secondary habitats. Despite this common pattern and the frequency with which benefits of small seed size for early successional species (large number, enhanced dispersal potential) have been discussed, little attention has focused on the advantages of large seeds for species that regenerate in closed, late successional associations.

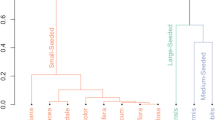

It is generally considered that large seeds enhance seedling survivorship at low light intensities. However, light intensity is only one of several factors that differ between shaded and sunlit habitats. This review examines microclimatic and biotic differences between shaded subcanopy habitats in mature tropical forests and those in sunlit, light gap habitats in which the early stages of tropical forest succession occur. Each factor is examined as a possible selective agent responsible for maintaining seed size differences between two guilds of tropical rainforest trees; the pioneer species that have small seeds and typically become established in large, sunlit gaps in the forest canopy and the persistent, relatively shade-tolerant species that have larger seeds and produce seedlings that survive for variable periods of time in the shade beneath the forest canopy.

Three microclimatic factors that differ in subcanopy and gap habitats are examined; temperature, moisture, and light intensity. It is unlikely that temperature has been an important selective agent in maintaining the differences in seed sizes observed between the pioneer and persistent tree guilds. However, greater desiccation stress in light gaps might prevent successful regeneration of larger seeds in this habitat and thus might impose the smaller mean seed sizes of pioneer species. Reduced light intensities in subcanopy habitats also could favor larger seeds in the persistent guild because large seed reserves might 1) enhance the abilities of seeds to persist until suitable light (or moisture) conditions arise by providing for metabolic requirements of seeds during quiescent periods, 2) provide secondary compounds for defense of persistent seedlings against pathogens and predators during periods of low energy availability, 3) provide energy for construction of large amounts of photosynthetic tissue needed to maintain a positive net energy balance when light conditions are just above the leaf light compensation point of the plant, 4) provide energy for growth into higher light intensity strata, and 5) provide nutrients for replacement of lost or damaged tissues in persistent seedlings.

Differences between soils in light gaps and subcanopy habitats are considered briefly. It is concluded that too little is known for predictions to be made regarding the probable effects of soil differences on the sizes of seeds able to survive in each habitat. Finally, differences between the two habitats in four biotic factors (competition, predation, pathogens, and mycorrhizal availability) are considered. Of these, greater competition for nutrients in the subcanopy habitat, and competition among co-germinating seedlings for light could have been important in favoring large seeds in the guild of persistent species. Pathogens are known to be more effective in shaded habitats, but data on seedling resistance to pathogens do not provide support for a role of seed size in enhancing resistance. Although differences in predation intensity and in mycorrhizal abundance in the two habitats have not been evaluated in the field, potential roles of these two factors in maintaining the seed size differential between these two guilds of forest trees are discussed.

Despite the existence of numerous potential benefits of large seed reserves, seed sizes often must reflect compromises between conflicting selective pressures. Environmental conditions (e.g., moisture availability) can impose upper limits on seed size. Enhanced dispersal potential and greater total propagule numbers from maternal energy reserves are benefits of small seed size that can counterbalance selection for large seed reserves. The interactions between selective forces in molding seed sizes are discussed in a final section.

Zusammenfassung

In feuchten, gemaessigten und tropischen Gebieten neigen die Pflanzenarten, die gewoehnlich geschlossene, schattige Habitate besiedeln, groessere Samen zu bilden als jene Arten, die in offenen, zerstoerten Habitaten wachsen. Obwohl dieses Muster haeufig zu finden ist, und der Vorteil von kleiner Samengroesse fuer frueh nachwachsende Arten diskutiert worden ist (grosse Anzahl, verbesserte Verbreitungsmoeglichkeit), wurde nur wenig darauf geachtet, welchen Vorteil grosse Samen einer Art geben koennen, die sich in einem geschlossenen, spaet nachwachsenden Verband regeneriert.

Es wird i.a. angenommen, dass bei geringer Lichtintensitaet grosse Samen das Ueberleben eines Saemlings verbessern. Lichtintensitaet ist jedoch nur einer von mehreren Faktoren, in denen sich schattige und sonnige Habitate unterscheiden. Dieser Uebersichtsartikel untersucht mikroklimatische und biotische Unterschiede zwischen schattigen, Habitaten im ausgewachsenen tropischen Urwald und sonnenreichen Habitaten in den fruehen Stadien der Wiederbewaldung. Jeder Faktor wird daraufhin untersucht, ob er eine moegliche Selektionskraft ist, die die Unterschiede in der Samengroesse zwischen den beiden Gruppen von tropischen Regenwaldbaeumen aufrechterhaelt: 1) die Pionier-Arten; sie haben kleine Samen und wachsen charakteristischer weise in grosseren lichten Partien des Waldes; 2) die sich hartnaeckig haltenden (persistenten), relativ viel Schatten tolerierenden Arten; sie haben die groesseren Samen und produzieren Saemlinge, die langere Zeitperioden im Schatten unterhalb der Baumkronen ueberleben.

Es werden die folgenden drei mikroklimatische Faktoren untersucht, die sich in Schattigen und lichtreichen Habitaten unterscheiden: Temperatur, Feuchtigkeit und Lichtintensitaet. Es ist unwahrscheinlich, dass Temperatur eine wichtige selektive Kraft ist, die die Unterschiede in der Samengroesse zwischen den Pionier-Arten und den persistenten Arten alfrechterhaelt. Austrocknungsstress koennte jedoch eine obere Grenze fuer die Groesse von Samen setzen, die in sonnenreichen Habitaten keimen. Somit koennte Austrocknungsstress die kleine Groesse der Samen bei Pionierpflanzen beeinflussen. Geringere Lichtintensitaet in Schattigen Habitaten koennte grosse Samen in der persistenten Baumgruppe favorisieren, da grosse Samenreserven 1) dem Samen ermoeglichen auszuharren, bis bessere Lichtverhaeltnisse (oder Feuchtigkeitsverhaeltnisse) entstehen, indem sie dem ruhenden Saemling die metabolischen Erfordernisse liefern; 2) sekundaeren Inhaltsstotte zur Verteidigung von Saemlingen gegen Pathogene und Pflanzenfresser in Perioden liefern, in denen wenig Energie zur Verfuegung steht; 3) Energie zur Herstellung grosser Mengen von photosynthetischem Gewebe liefern, das fuer ein positives Energiegleichgewicht notwendig ist; 4) Energie liefern, um in die hoeheren, lichtintensiveren Bereiche zu gelangen; 5) Naehrstoffe liefern, um zerstoertes oder verlorengegangenes Gewebe zu ersetzen.

Es werden hier kurz die Unterschiede zwischen den Boeden in lichten und schattigen Habitaten betrachtet. Es ergibt sich, dass zu wenig bekannt ist, um Voraussagen machen zu koennen, ob die verschiedenen Boeden in den unterschiedlichen Habitaten einen Einfluss auf die Groesse und die Ueberlebensfaehigkeit von Samen haben. Zum Schluss werden die Unterschiede zwischen den beiden Habitaten bez. vier biotischer Faktoren (Konkurrenz, Pflanzenfresser Pathogene und Pilzsymbiosen) betrachtet. Von diesen Faktoren koennte die Konkurrenz um Naehrstoffe in schattigen Habitaten und die Konkurrenz um Licht zwischen gleichzeitig keimenden Saemlingen wesentlich sein, dass in der Gruppe der persistenten Arten grosse Samen favorisiert werden. Bekanntlich sind Pathogene wirkungsvoller in schattigen Habitaten. Untersuchungen ueber die Widerstandskraft von Saemlingen gegen Pathogene zeigen aber nicht, dass die Samengroesse den Widerstand gegen Pathogene verbessert. Bis jetzt wurde im Freiland nicht untersucht, ob sich beide Habitate in der Häufigkeit von Pflanzenfressern und dem Vorkommen von Pilzsymbionten unterscheiden. Es werden hier die potentiellen Moeglichkeiten dieser beiden Faktoren zur Erhaltung der Unterschiede in der Samengroesse zwischen den beiden Gruppen von Baeumen diskutiert.

Obwohl eine Anzahl von moeglichen Vorteilen fuer eine grosse Samengroesse existiert, spiegelt die Groesse des Samens einen Kompromiss zwischen gegensaetzlich wirkenden Selektionskraeften wider. So koennen Bedingungen der Umgebung (z.B. Verfuegbarkeit von Wasser) die obere Grenze der Samengroesse bestimmen. Die Selektion fuer verbesserte Verbreitungsmoeglichkeit und die Selektion fuer eine groessere Anzahl von Nachkommen bevorzugen dagegen eine kleine Samengroesse. Sie koennen somit der Selektion fuer grosse Samengroesse entgegenwirken. Abschliessend wird diskutiert in welcher Art und Weise sich die verschiedenen Selektionskraefte bei der Bildung der Samengroesse gegenseitig beeinflussen.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature Cited

Ashton, P. S. 1978. Crown characteristics of tropical trees. Pages 591–615in P. B. Tom-linson & M. H. Zimmerman (eds.), Tropical trees as living systems. Cambridge Uni-versity Press, New York.

Augspurger, C. K. 1983a. Seed dispersal by the tropical treePlatypodium elegans, and the escape of its seedlings from fungal pathogens. J. Ecol.71: 759–771.

—. 1983b. Offspring recruitment around tropical trees: Changes in cohort distance with time. Oikos40: 189–196.

—. 1984. Seedling survival of tropical tree species: Interactions of dispersal distance, light-gaps, and pathogens. Ecology65: 1705–1712.

— &C. K. Kelly. 1984. Pathogen mortality of tropical tree seedlings: Experimental studies of the effects of dispersal distance, seedling density, and light conditions. Oeco-logia61: 211–217.

Baker, H. G. 1972. Seed weight in relation to environmental conditions in California. Ecology53: 997–1010.

Barnard, R. C. 1956. Recruitment, survival and growth of timber tree seedlings in natural tropical rainforest. Malayan Forest.19: 156–161.

Baylis, G. T. S. 1959. Effect of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza on the growth ofGriselinia littoralis (Cornaceae). New Phytol.58: 274–280.

—. 1967. Experiments on the ecological significance of phycomycetous mycorrhizas. New Phytol.66: 231–243.

—. 1971. Endogenous mycorrhizae synthesized inLeptospermum (Myrtaceae). New Zealand J. Bot.9: 293–296.

—. 1975. The magnolioid mycorrhiza and myctotrophy in root systems derived from it. Pages 373–389in F. E. Sanders, B. Mosse & P. B. Tinker (eds.), Endomycorrhizas. Academic Press, London.

Bazzaz, F. A. &S. T. A. Pickett. 1980. Physiological ecology of tropical succession: A comparative review. Ann. Rev. Ecol. Syst.11: 287–310.

Becker, P. &M. Wong. 1985. Seed dispersal, seed prédation and juvenile mortality ofAglaia sp. (Meliaceae) in a lowland dipterocarp rainforest. Biotropica17: 230–237.

Beard, J. S. 1946.Mora forests of Trinidad, British West Indies. J. Ecol.33: 173–192.

Bell, T. I.W. 1972. Manejo de los bosques deMora en Trinidad con especial referenda a la reserva forestal de Matura. Bol. Inst. Forest. Latino Amer. Invest.41–42: 3–46.

Bewley, J. K. &M. Black. 1978. Physiology and biochemistry of seeds in relation to germination, 1. Springer-Verlag, New York.

——. 1982. Physiology and biochemistry of seeds in relation to germination, 2. Springer-Verlag, New York.

Bieleski, R. L. 1959. Factors affecting growth and distribution of kauri (Agathis australis Salisb.) I. Effect of light on establishment of kauri and ofPhyllocladus trichomanoides D. Don, II. Effect of light intensity on seedling growth, III. Effects of temperature and soil conditions. Austral. J. Bot.7: 252–294.

Bjorkmann, O. &M. M. Ludlow. 1972. Characterization of the light climate on the floor of a Queensland rainforest. Carnegie Inst. Wash. Year Book71: 85–94.

Black, J. N. 1956. The influence of seed size and depth of sowing on pre-emergence and early vegetative growth of subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum L.). Austral. J. Agric. Res.7: 98–109.

—. 1957. The early vegetative growth of three strains of subterranean clover in relation to size of seed. Austral. J. Agric. Res.8: 1–14.

—. 1958. Competition between plants of different initial seed size in swards of sub-terranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum L.) with particular reference to leaf area and the light microclimate. Austral. J. Agric. Res.9: 299–318.

—. 1959. Seed size in herbage legumes. Herbage Abstr.29: 235–241.

— &G. N. Wilkinson. 1963. The role of time of emergence in determining the growth of individual plants in swards of subterranean clover (Trifolium subterraneum L.). Austral. J. Agric. Res.14: 628–638.

Brokaw, N. V. L. 1985. Gap-phase regeneration in a tropical forest. Ecology66: 682–687.

Brown, W. H. &D. M. Mathews. 1914. Philippine dipterocarp forests. Philipp. J. Sci.9: 413–516.

Burgess, P. F. 1970. An approach towards a silvicultural system for the hill forests of the Malay Peninsula. Malayan Forester33: 126–134.

Chazdon, R. L. &N. Fetcher. 1984. Photosynthetic light environments in a lowland tropical rain forest in Costa Rica. J. Ecol.72: 553–564.

Cheke, A. S., W. Nanakorn &C. Yankoses. 1979. Dormancy and dispersal of seeds of secondary forest species under the canopy of a primary tropical rain forest in northern Thailand. Biotropica11: 88–95.

Coley, P. D. 1983. Herbivory and defensive characteristics of tree species in a lowland tropical forest. Ecol. Monogr.53: 209–233.

Connell, J. H. 1971. On the role of natural enemies in preventing competitive exclusion in some marine animals and in rainforest trees. Pages 298–312in P. J. den Boer & G. Gradwell (eds.), Dynamics of populations. Proc. Adv. Study Inst., Oosterbeek, 1970. Cen. Ag. Publ. and Doc. Wageningen.

Cooper, K. M. 1975. Growth responses to the formation of endotrophic mycorrhizas inSolanum, Leptospermum and New Zealand ferns. Pages 391–407in F. E. Sanders, B. Mosse & P. B. Tinker (eds.), Endomycorrhizas. Academic Press, London.

Denslow, J. S. 1980a. Gap partitioning among tropical rainforest trees. Biotropica (suppl.)12: 47–55.

—. 1980b. Notes on the seedling ecology of large seeded species of Bombacaceae. Biotropica12: 220–222.

— &T. C. Moermond. 1982. The effect of accessibility on rates of fruit removal from tropical shrubs: An experimental study. Oecologia54: 170–176.

Evans, G. C. 1939. Ecological studies on the rain forest of southern Nigeria II. The atmospheric environment conditions. J. Ecol.27: 432–482.

—,T. C. Whitmore &Y. K. Wong. 1960. The distribution of light reaching the ground vegetation in a tropical rain forest. J. Ecol.48: 193–204.

Feeney, P. P. 1975. Biochemical coevolution between plants and their insect herbivores. Pages 3–19in L. E. Gilbert & P. H. Raven (eds.), Coevolution of animals and plants. University of Texas Press, Austin.

Fetcher, N., B. R. Strain &S. F. Oberbauer. 1983. Effects of light regime on the growth, leaf morphology, and water relations of seedlings of two species of tropical trees. Oeco-logia58: 314–319.

Foster, S. A. &C. H. Janson. 1985. The relationship between seed size and establishment conditions in tropical woody plants. Ecology66: 773–780.

Freeland, W. J. &D. H. Janzen. 1974. Strategies in herbivory by mammals: The role of plant secondary compounds. Amer. Naturalist108: 269–289.

Garrard, A. 1955. The germination and longevity of seeds in an equatorial climate. Gard. Bull. Singapore14: 534–535.

Garwood, N. C. 1983. Seed germination in a seasonal tropical forest in Panama: A com-munity study. Ecol. Monogr.53: 159–181.

Gerdemann, J. W. 1965. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza formed on maize and tulip tree byEndogone fasciculata. Mycologia57: 562–575.

Gillespie, J. H. 1977. Natural selection for variances in offspring numbers: A new evo-lutionary principle. Amer. Naturalist110: 1010–1014.

Grime, J. P. 1966. Shade avoidance and tolerance in flowering plants. Pages 281–301in R. Bainbridge, G. C. Evans & O. Rackham (eds.), Light as an ecological factor. Blackwell, Oxford.

—. 1979. Plant strategies and vegetation processes. John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

— &D. W. Jeffrey. 1965. Seedling establishment in vertical gradients of sunlight. J. Ecol.53: 621–642.

Grubb, P. J. &T. C. Whitmore. 1966. A comparison of montane and lowland rainforest in Ecuador. II. The climate and its effects on the distribution and physiognomy of the forests. J. Ecol.543: 303–333.

Guevara, S. &A. Gomez-Pompa. 1972. Seeds from surface soils in a tropical region of Veracruz. J. Arnold Arb.53: 312–335.

Hall, J. B. &M. D. Swaine. 1980. Seed stocks in Ghanaian forest soils. Biotropica12: 256–263.

-. 1981. Distribution and ecology of vascular plants in a tropical rainforest. Geo-botany 1. Dr. W. Junk, The Hague.

Hamilton, W. D. 1964a. The genetical evolution of social behaviour I. J. Theor. Biol.7: 1–16.

—. 1964b. The genetical evolution of social behaviour II. J. Theor. Biol.7: 17–52.

— &R. M. May. 1977. Dispersal in stable habitats. Nature269: 578–581.

Harper, J. L. 1977. Population biology of plants. Academic Press, London.

— &R. A. Benton. 1966. The behaviour of seeds in soil, part 2. The germination of seeds on the surface of a water supplying substrate. J. Ecol.54: 151–166.

— &J. N. Clatworthy. 1963. The comparative biology of closely related species. VI. Analysis of the growth ofTrifolium repens andT. fragiferum in pure and mixed pop-ulations. J. Exp. Bot.14: 172–190.

—,P. H. Lovell &K. G. Moore. 1970. The shapes and sizes of seeds. Annual Rev. Ecol. Syst.1: 327–356.

— &M. Obeid. 1967. Influence of seed size and depth of sowing on the establishment and growth of varieties of fiber and oil seed flax. Crop. Sci.7: 527–532.

Harrington, J. F. 1972. Seed storage and longevity. Pages 145–246in T. T. Kozlowski (ed.), Seed biology. Academic Press, New York.

Hartshorn, G. S. 1978. Treefalls and tropical forest dynamics. Pages 617–638in P. B. Tomlinson & M. H. Zimmermann (eds.), Tropical trees as living systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

—. 1980. Neotropical forest dynamics. Biotropica12(suppl.): 23–30.

Havel, J. J. 1965. Plantation establishment of Klinki pine (Araucaria hunsteinii) in New Guinea. Empire Forest. Rev.44: 172–187.

Hermann, R. K. &W. W. Chilcote. 1965. Effect of seedbeds on germination and survival of Douglas-fir. Res. Pap. (Forest. Mgmt. Res.) Oregon Forest. Res. Lab.4: 1–28.

Higgens, M. L. 1979. Intensity of seed predation onBrosimum utile by mealy parrots. Biotropica11: 80.

Hladik, C. M. &A. Hladik. 1967. Observations sur le rôle des primates dans la disse-mination des végétaux de la forét gavonaise. Biol. Gabon.3: 43–58.

Hopkins, M. S. &A. W. Graham. 1983. The species composition of soil seed banks beneath lowland tropical rainforests in North Queensland, Australia. Biotropica15: 90–99.

Horn, H. S. 1971. The adaptive geometry of trees. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

Howe, H. F. &W. M. Richter. 1982. Effects of seed size on seedling size inVirola surinamensis; a within and between tree analysis. Oecologia53: 347–351.

—,E. W. Schupp &L. C. Westley. 1985. Early consequences of seed dispersal for a neotropical tree (Virola surinamensis). Ecology66: 781–791.

— &J. Smallwood. 1982. Ecology of seed dispersal. Annual Rev. Ecol. Syst.13: 201–228.

— &G. A. Vande Kerckhove. 1980. Nutmeg dispersal by tropical birds. Science210: 925–927.

——. 1981. Removal of wild nutmeg (Virola surinamensis) crops by birds. Ecology62: 1093–1106.

Jackson, J. F. 1981. Seed size as a correlate of temporal and spatial patterns of seed fall in a Neotropical forest. Biotropica13: 121–130.

Janos, D. P. 1975a. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and plant growth in a Costa Rican lowland rainforest. Ph.D. Dissertation. The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. 172 pp.

—. 1975b. Effects of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae on lowland tropical rainforest trees. Pages 437–446in F. E. Sanders, B. Mosse & P. B. Tinker (eds.), Endomycorrhizas. Academic Press, London.

—. 1977. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae affect the growth ofBactris gasipaes. Principes21: 12–18.

—. 1980. Mycorrhizae influence tropical succession. Biotropica12 (suppl.): 56–64.

Janse, J. M. 1896. Les endophytes radicaux de quelques plantes Javanaises. Ann. Jard. Bot. Buitenzorg14: 53–212.

Janson, C. H. 1983. Adaptation of fruit morphology to dispersal agents in a neotropical forest. Science219: 187–189.

Janzen, D. H. 1969. Seed-eaters versus seed size, number, toxicity and dispersal. Evolution23: 1–27.

—. 1970. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. Amer. Nat-uralist104: 501–528.

—. 1971. Seed predation by animals. Annual Rev. Ecol. Syst.2: 465–483.

—. 1974. Tropical blackwater rivers, animals, and mast fruiting by the Dipterocar-paceae. Biotropica6: 69–103.

—. 1978. The ecology and evolutionary biology of seed chemistry as relates to seed predation. Pages 163–206in J. B. Harborne (ed.), Biochemical aspects of plant and animal coevolution. Academic Press, New York.

—. 1982a. Fruit traits, and seed consumption by rodents, ofCrescentia alata (Big-noniaceae) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Amer. J. Bot.69: 1258–1268.

— 1982b. Removal of seeds from horse dung by tropical rodents: Influence of habitat and amount of dung. Ecology63: 1887–1900.

—. 1982c. Seeds in tapir dung in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica. Brenesia19/ 20: 129–135.

—. 1982d. Seed removal from fallen guanacaste fruits (Enterolobium cyclocarpum) by spiny pocket mice (Liomys salvini). Brenesia19/20: 425–429.

— 1983. Food webs: Who eats what, why, how, and with what effects in a tropical forest? Pages 167–182in F. B. Golley (ed.), Tropical rain forest ecosystems. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

Johnston, A. 1949. Vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhiza in Sea island cotton and other tropical plants. Trop. Agric. (Trinidad)26: 118–121.

Jordano, P. 1983. Fig seed predation and dispersal by birds. Biotropica15: 38–41.

Kaufman, J. H. 1962. Ecology and social behavior of the coatiNasau nasau on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool.60: 95–222.

Keay, R. W. J. 1960. Seeds in forest soil. Nigerian Forest. Inf. Bull.4: 1–4.

Keever, C. 1973. Distribution of major forest species in south-eastern Pennsylvania. Ecol. Monogr.43: 303–327.

Kiew, R. 1982. Germination and seedling survival in kemenyan,Stryax benzoin. Malayan Forest.45: 69–80.

Kiltie, R. A. 1981. Distribution of palm fruits on a rain forest floor: Why white-lipped peccaries forage near objects. Biotropica13: 141–145.

Kira, T. 1978. Community architecture and organic matter dynamics in tropical lowland rainforests of Southeast Asia with special reference to Pasoh forest, West Malaysia. Pages 561–590in P. B. Tomlinson & M. H. Zimmermann (eds.), Tropical trees as living systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kleinschmidt, G. D. &J. W. Gerdeman. 1972. Stunting of citrus seedlings in fumigated nursery soils related to the absence of endophytes. Phytopathology62: 1447–1453.

Koebernik, J. 1971. Germination of palm seed. Principes15: 134–137.

Koroleff, A. 1954. Leaf litter as a killer. J. Forest.52: 178–182.

Kozlowski, T. T. 1971. Growth and development of trees. Vol. I. Academic Press, New York.

Kramer, F. 1933. De Natuurlijke verjonging in het Goenoeng-Gedehcomplex. Tectonia26: 156–185.

Lawson, G. W., K. O. Armstrong-Mensah &J. B. Hall. 1970. A catena in tropical moist semi-deciduous forest near Kade, Ghana. J. Ecol.58: 371–398.

Lebron, M. L. 1979. An autecological study ofPalicouria riparia Bentham as related to rain forest disturbance in Puerto Rico. Oecologia42: 31–46.

Levin, D. A. 1971. Plant phenolics: An ecological perspective. Amer. Naturalist105: 157–182.

Liew, T. C. 1973. Occurrence of seeds in virgin forest top soil with special reference to secondary species in Sabah. Malayan Forest.36: 185–193.

— &F. O. Wong. 1973. Density, recruitment, mortality and growth of dipterocarp seedlings in virgin and logged over forest in Sabah. Malayan Forest.36: 3–15.

Longman, K. A. &J. Jenik. 1974. Tropical forest and its environment. Longman, London.

Lopez, Q. M. M. &C. Vazquez-Yanes. 1976. Estudio sobre germination de semillas en condiciones naturales controlades. Pages 250–262in A. Gomez-Pompa, S. del Amo R., C. Vazquez-Yanes & A. Butanda C. (eds.), Regeneration de selvas. Inst. Investi-gaciones sobre Recursos Bioticos, Cia. Editorial Continental, S.A. Mexico.

Marrero, J. 1943. A seed storage study of some tropical hardwoods. Caribb. For.4: 99–106.

Maury-Lechon, G., A. M. Hassan &D. R. Bravo. 1981. Seed storage ofShorea parviflora andDipterocarpus humeratus. Malayan Forest.44: 267–280.

Mayer, A. M. &A. Poljakoff-Mayber. 1982. The germination of seeds. Pergamon Press, New York.

McKey, D. 1975. The ecology of coevolved seed dispersal systems. Pages 159–191in L. E. Gilbert & P. H. Raven (eds.), Coevolution of animals and plants. University of Texas Press, Austin.

—. 1978. Soils, vegetation and seed eating by black colobus monkeys. Pages 423–437in G. G. Montgomery (ed.), The ecology of arboreal folivores. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

Meijer, W. 1970. Regeneration of tropical lowland forest in Sabah, Malaysia, forty years after logging. Malayan Forest.33: 204–229.

Michod, R. E. &W. D. Hamilton. 1980. Coefficients of relatedness in sociobiology. Nature288: 694–697.

Morris, D. 1962. The behavior of green acouchi (Myoprocta pratti) with special reference to scatter hoarding. Proc. Zool. Soc. Lond.139: 701–732.

Mosse, B. 1973. Advances in the study of vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizae. Annual Rev. Phytopathol.11: 171–196.

Ng, F. S. P. 1973. Germination of fresh seeds of Malaysian trees L. Malayan Forest.36: 54–65.

—. 1975. The fruits, seeds and seedlings of Malayan trees II. Malayan Forest.38: 33–99.

—. 1978. Strategies of establishment in Malayan forest trees. Pages 129–162in P.B. Tomlinson & M. H. Zimmermann (eds.), Tropical trees as living systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

—. 1980. Germination ecology of Malaysian woody plants. Malayan Forest.43: 406–437.

Nienstadt, H. &J. S. Olson. 1961. Effects of photoperiod and source on seedling growth of Eastern Hemlock. Forest. Sci.7: 81–96.

Odum, H. T., G. Drewry &J. R. Kline. 1970. Climate at El Verde, 1963–1966. Pages B 347–418in H. T. Odum & R. F. Pigeon (eds.), A tropical rain forest. U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Orians, G. H. &D. H. Janzen. 1974. Why are embryos so tasty? Amer. Naturalist108: 581–592.

Poore, M. E. D. 1968. Studies in Malaysian rainforests. I. The forest on Triassic sediments in Jengka Forest Reserve. J. Ecol.56: 143–196.

Putz, F. E. 1983. Treefall pits and mounds, buried seeds, and the importance of soil disturbance to pioneer trees on Barro Colorado Island, Panama. Ecology64: 1069–1074.

—,P. D. Coley, K. Lu, A. Montalvo &A. Aiello. 1983. Uprooting and snapping of trees: Structural determinants and ecological consequences. Canad. J. Forest. Res.13: 1011–1020.

Queller, D. C. 1983. Kin selection and conflict in seed maturation. J. Theor. Biol.100: 153–172.

Redhead, J. F. 1968. Mycorrhizal associations in some Nigerian forest trees. Trans. Brit. Mycol. Soc.51: 485–492.

Rhoades, K. F. &R. G. Cates. 1976. Toward a general theory of plant antiherbivore chemistry. Pages 168–213in J. W. Wallace & R. L. Mansell (eds.), Biochemical inter-actions between plants and insects. Plenum, New York.

Richards, P. W. 1952. The tropical rainforest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Rockwood, L. L. 1984. Seed weight as a function of life form, elevation and life zone in neotropical forests. Biotropica17: 32–39.

Roff, D. A. 1975. Population stability and the evolution of dispersal in a heterogenous environment. Oecologia19: 219–237.

Rosensweig, M. L. &P. W. Sterner. 1970. Population ecology of desert rodent commu-nities: Body size and seed husking as bases for heteromyid coexistences. Ecology51: 217–224.

Roth, L. F. &A. J. Ricker. 1943. Influence of temperature, moisture, and soil reaction on the damping-off of red pine seedlings byPythium andRhizoctonia. J. Agric. Res.67: 273–293.

Salisbury, E. J. 1942. The reproductive capacity of plants. G. Bell and Sons, London.

Salisbury, F. B. &C. Ross. 1969. Plant physiology. Wadsworth, Belmont, California.

Salisbury, S. E. 1974. Seed size and mass in relation to environment. Proc. Royal Soc. Lond.B186: 83–88.

Saski, S. &T. Mori. 1981. Growth responses of dipterocarp seedlings to light. Malayan Forest.44: 319–345.

Schulz, J. P. 1960. Ecological studies on the rainforest in northern Suriname. Verh. Kon. Ned. Akad. Wetensch. Afd. natuurk. Tweede Sect.53: 1–267.

Silvertown, J. W. 1981. Seed size, lifespan, and germination date as coadapted features of plant life history. Amer. Naturalist118: 860–864.

Smith, A. J. 1975. Invasion and ecesis of bird disseminated woody plants in a temperate forest sere. Ecology56: 19–34.

Smythe, N. 1970. Relationships between fruiting seasons and seed dispersal methods in a neotropical forest. Amer. Naturalist104: 25–35.

Stebbins, G. L. 1974. Flowering plants: Evolution above the species level. Arnold, London.

Strathman, R. 1974. The spread of sibling larvae of sedentary marine invertebrates. Amer. Naturalist108: 29–44.

Sydes, C. &J. P. Grime. 1981. Effects of tree leaf litter on herbaceous vegetation in deciduous woodland II. An experimental investigation. J. Ecol.69: 249–262.

Tang, H. T. &C. Tamari. 1973. Seed description and storage tests of some dipterocarps. Malayan Forest.36: 38–53.

Vaartaja, O. 1952. Forest humus quality and light conditions as factors influencing damp-ing-off. Phytopathology42: 501–506.

—. 1962. The relationship of fungi to survival of shaded tree seedlings. Ecology43: 547–549.

Vazquez-Yanes, C. 1976. Estudios sobre la ecofisiologia de la germination en una zona calido-humeda de Mexico. Pages279–387in A. Gomez-Pompa, C. Vazquez-Yanes, S. del Arno Rodriquez & A. Butanda Cervera (eds.), Investigaciones sobre la regeneration de selvas altas en Veracruz, Mexico. Cia. Compania Editorial Continental, Mexico.

Voight, G. K. 1971. Mycorrhizae and nutrient mobilization. Pages 122–131in F. Hacskaylo (ed.), Mycorrhizae. U.S.D.A. Forest Serv. Misc. Publ. 1189. U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, D.C.

Westoby, M. &B. Rice. 1982. Evolution of the seed plants and inclusive fitness of plant tissues. Evolution36: 713–724.

Whitmore, T. C. 1975. Tropical rainforests of the Far East. Clarendon Press, Oxford.

—. 1978. Gaps in the forest canopy. Pages 639–655in P. B. Tomlinson & M. H. Zimmermann (eds.), Tropical trees as living systems. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Whittaker, R. H. 1975. Communities and ecosystems, 2nd ed. Macmillan, New York.

Williams, W. A., J. N. Black &C. M. Donald. 1968. Effect of seed weight on the vegetative growth of competing annual trifoliums. Crop Sci.8: 660–663.

Willson, M. F. &N. Burley. 1983. Mate choice in plants: Tactics, mechanisms, and consequences. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

Yap, S. K. 1981. Collection, germination, and storage of dipterocarp seeds. Malayan Forest.44: 281–230.

Yoda, K. 1974. Three dimensional distribution of light intensity in a tropical rainforest of West Malyasia. Jap. J. Ecol.24: 247–254.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Foster, S.A. On the adaptive value of large seeds for tropical moist forest trees: A review and synthesis. Bot. Rev 52, 260–299 (1986). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860997

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02860997