Abstract

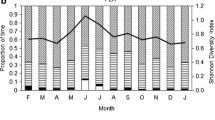

Lesser bushbabies (Galago senegalensis moholi)were studied by radiotracking over a 2-year period (August 1975 to August 1977)at a thornveld study site in the Northern Transvaal, South Africa. It was confirmed that the diet consisted exclusively of plant exudates (gums) and arthropods;available fruits were never eaten. The gums were taken from the trunks and branches of Acaciatrees, particularly from Acacia karroo(the major source), from A. tortilis,and to a small extent from A. nilotica.Chemical analysis shows that gums consist predominantly of carbohydrates and water, with small quantities of fiber, protein, and minerals (notably calcium, magnesium, and potassium). Thus, the gums probably present first and foremost a source of carbohydrate in the diet of the lesser bushbaby, though it seems likely that special mechanisms must exist for digestion of the polymerized pentose and hexose sugars. The calcium content of the gums (approx. 1% by weight) is probably significant in offsetting the low calcium content of the arthropod prey, and their high calcium:phosphorus ratio may well counterbalance the low calcium:phosphorus ratio of the arthropods. The gums are apparently produced largely in response to insect activity. Larvae of beetles (families Cerambycidae,Buprestidae, and Elateridae) and of moths (family Coccidae) bore channels beneath the tree surface, and gum is liberated through apertures made during invasion of the host Acacia.Fly larvae (family Odiniidae) may also develop in the gumfilled cavities. Gum exuding onto the surface is collected by the bushbabies on regular nightly visits, and firm evidence was obtained, in the form of characteristic marks on trap baseboards and certain gum sites, that the toothscraper in the lower jaw is used to scoop away gum from tree surfaces. Foraging for, and feeding upon, gum increased during the winter months, which may be particularly harsh in certain years. In the especially cold winter covered by the study, insect availability was minimal and the lesser bushbabies fed mainly on gum, with some of them reducing their total activity period during the night. Gums are available throughout the year and detailed records indicated no clearcut seasonal pattern of gum production. They are therefore an important yearround food resource for the lesser bushbabies. Feeding on gums has been reported for a wide range of primate species in recent years (especially for various species of the families Cheirogaleidae, Lorisidae, and Callitrichidae), and these plant exudates must now be regarded as an important dietary category within the order Primates.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Acocks, J. P. H. (1975). Veld types of South Africa.Mem. Bot. Surv. S. Afr. 40: 1–28.

Anderson, D. M. W. (1978). Chemotaxonomic aspects of the chemistry ofAcacia gum exudates.Kew Bull. 32(3): 529–536.

Anderson, D. M. W., and Bell, P. C. (1974). The composition and properties of gum exudates from subspecies ofAcacia tortilis.Phytochemistry 13: 1875–1877.

Anderson, D. M. W., and Dea, I. C. M.(1969). Recent advances in the chemistry ofAcacia gums.J. Soc. Cosmet. Chem. 3: 1–16.

Anderson, D. M. W., and Pinto, G. (1980). Variations in the composition and properties of the gum exuded byAcacia karroo Hayne in different African localities.Bot. J. Lin. Soc. (in press).

Anderson, D. M. W., Hendrie, A., and Munro, A. C. (1972). The amino acid and amino sugar composition of some plant gums.Phytochemistry 11: 733–736.

Bearder, S. K. (1968).Territorial and Intergroup Behaviour of the Lesser Bushbaby, Galago senegalensis moholi (A. Smith), in Semi-natural conditions and in the Field, unpublished MSc. dissertation, University of the Witwatersrand.

Bearder, S. K. (1974).Aspects of the Ecology and Behaviour of the Thick-Tailed Bushbaby,Galago crassicaudatus, Ph.D. thesis, University of the Witwatersrand.

Bearder, S. K., and Martin, R. D. (1980). The social organization of a nocturnal primate revealed by radio tracking. In Amlaner, C. J., Jr., and Macdonald, D. W. (eds.),A Handbook on Biotelemetry and Radio Tracking, Pergamon Press, London and New York, pp. 633–648.

Booth, A. N., and Hendrickson, A. P. (1963). Physiologic effects of three microbial polysaccharides on rats.Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 5: 478–484.

Buettner-Janusch, J., and Andrew, R. J. (1962). The use of incisors by primates in grooming.Am. J. Phys. Anthropol. 20: 127–129.

Charles-Dominique, P. (1976). Les gommes dans le regime alimentaire deCoua cristata a Madagascar.L’Oiseau Rev. Franc. Ornithol. 46: 174–178.

Charles-Dominique, P. (1977).Ecology and Behaviour of Nocturnal Primates, Duckworth, London.

Charles-Dominique, P., and Bearder, S. K. (1979). Field studies of lorisid behaviour: The Iorisids of Gabon; the galagines of South Africa. In Doyle, G. A., and Martin, R. D. (eds.),The Study of Prosimian Behavior, Academic Press, New York, pp. 567–629.

Coimbra-Filho, A. F., and Mittermeier, R. A. (1976). Exudate-eating and tree-gouging in marmosets.Nature 262(5569): 630.

Coimbra-Filho, A. F., and Mittermeier, R. A. (1977). Tree-gouging, exudate-eating and the short-tusked condition inCallithrix andCebuella. In Kleiman, D. G. (ed.),The Biology and Conservation of the Callitrichidae, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 105–115.

Glicksman, M. (1969).Gum Technology in the Food Industry, Academic Press, New York and London.

Gray, P. (1961).The Encyclopedia of the Biological Sciences, Chapman & Hall, London.

Hershkovitz, P. (1977).Living New World Monkeys (Platyrrhini) with an Introduction to Primates, Vol. 1, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Hladik, C. M. (1979). Diet and ecology of prosimians. In Doyle, G. A., and Martin, R. D. (eds.),The Study of Prosimian Behavior, Academic Press, New York.

Hove, E. L., and Herndon, F. J. (1957). Growth of rabbits on purified diets.J. Nutr. 63: 193–199.

Howes, F. N. (1949).Vegetable Gums and Resins, Chronica Botanical, Waltham, Mass.

Izawa, K. (1975). Foods and feeding behaviors of monkeys in the upper Amazon basin.Primates 16: 295–316.

Kinzey, W. G., Rosenberger, A. L., and Ramirez, M. (1975). Vertical clinging and leaping in a neotropical anthropoid.Nature 255(5506): 327–328.

Martin, E. A. (1976).A Dictionary of Life Sciences, Macmillan, London.

Martin, R. D. (1972). Adaptive radiation and behaviour of the Malagasy lemurs.Phil. Trans. R. Soc. London 264: 295–352.

Martin, R. D. (1979). Phylogenetic aspects of prosimian behaviour. In Doyle, G. A., and Martin, R. D. (eds.),The Study of Prosimian Behavior, Academic Press, New York.

Martin, R. D., Rivers, J. R. W., and Cowgill, U. M. (1976). Culturing mealworms as food for animals in captivity.Int. Zool. Yb. 16:63–70.

Monke, J. V. (1941). Non-availability of gum acacia as a glycogenic foodstuff in the rat.Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 46: 178–179.

Mueller-Dombois, D., and Ellenberg, H. (1974).Aims and Methods of Vegetation Ecology, Wiley, New York.

Petter, J. J. (1978). Ecological and physiological adaptations of five sympatric nocturnal lemurs to seasonal variations in food production. In Chivers, D. J., and Herbert, (eds.),Recent Advances in Primatology, Vol. I, Academic Press, London, pp. 211–223.

Petter, J. J., Schilling, A., and Pariente, G. (1971). Observations eco-ethologiques sur deux Lemuriens malgaches nocturnes:Phaner furcifer et Microcebus coquereli.Terre Vie 25(3): 287–327.

Ramirez, M. F., Freese, C. H., and Revilla, C. J. (1977). Feeding ecology of the pygmy marmoset,Cebuella pygmaea, in northeastern Peru. In Kleiman, D. G. (ed.),The Biology and Conservation of the Callitrichidae, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., pp. 91–104.

Sauer, E. G. F., and Sauer, E. M. (1963). The South West African bushbaby of theGalago senegalensis group.J. S. W. Afr. Sei. Soc. Windhoek 16: 5–36.

Szalay, F. S., and Seligsohn, D. (1977). Why did the strepsirhine tooth comb evolve?Folia Primatol. 27: 75–82.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bearder, S.K., Martin, R.D. Acacia gum and its use by bushbabies,Galago senegalensis (Primates: Lorisidae). Int J Primatol 1, 103–128 (1980). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02735592

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02735592