Abstract

OBJECTIVE: To determine the effects of physician gender on rates of Pap testing, mammography, and cholesterol testing when identifying and adjusting for demographic, psycho-social, and other patient variables known to influence screening rates.

DESIGN: A prospective design with baseline and six-month follow-up assessments of patients’ screening status.

SETTING: Twelve community-based group family practice medicine offices in North Carolina.

PARTICIPANTS: 1,850 adult patients, aged 18–75 years (six-month response rate, 83%), each of whom identified one of 37 physicians as being his or her regular care provider.

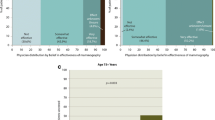

MAIN RESULTS: Where screening was indicated at baseline, the patients of the women physicians were 47% more likely to get a Pap test [odds ratio (OR)=1.47, 95% confidence interval (CI)=1.05, 2.04] and 56% more likely to get a cholesterol test (OR=1.56, 95% CI=1.08, 2.24) during the study period than were the patients of the men physicians. For mammography, the younger patients (aged 35–39 years) of the women physicians were screened at a much higher rate than were the younger patients of the men physicians (OR=2.69, 95% CI=0.98, 7.34); however, at older ages, the patients of the women and the men physicians had similar rates of screening.

CONCLUSIONS: In general, the patients of the women physicians were screened at a higher rate than were the patients of the men physicians, even after adjusting for important patient variables. These findings were not limited to gender-specific screening activities (e.g.. Pap testing), as in some previous studies. However, the patients of the women physicians were aggressively screened for breast cancer at the youngest ages, where there is little evidence of benefit from mammography. Larger studies are needed to determine whether this pattern of effects reflects a broader phenomenon in primary care.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hayward RA, Shapiro MF, Freeman HE. Corey CR. Who gets screened for cervical and breast cancer? Results from a new national survey. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:1177–81.

Centers for Disease Control. Use of mammography-United States, 1990. MMWR. 1990;39:621–9.

Makuc DM. Freid VM. Kleinman JC. National trends in the use of preventive health care by women. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:21–6.

Harlan LC, Bernstein AB. Kessler LG. Cervical cancer screening: who is not screened and why? Am J Public Health. 1991;81:885–90.

Lewis CE. Disease prevention and health promotion practices of primary care practices in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 1986;4(suppl):9–16.

Woolhandler S, Himmelstein DU. Reverse targeting of preventive care due to lack of health insurance. JAMA. 1988;259:2872–4.

The NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium. Screening mammography: a missed clinical opportunity? Results of the NCI Breast Cancer Screening Consortium and National Health Interview Survey studies. JAMA. 1990;264:54–8.

Vogel VG. Graves DS, Vernon SW. Lord JA, Winn RJ, Peters GN. Mammographic screening of women with increased risk of breast cancer. Cancer. 1990;66:1613–20.

Rakowski W, Jube CE, Marcus BH, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Abrams DB. Assessing elements of women’s decisions about mammography. Health Psychol. 1992;11:111–8.

Rakowski W, Fulton JP, Feldman JP. Women’s decision making about mammography: a replication of the relationship between stages of adoption and decisional balance. Health Psychol. 1993;12:209–14.

Kruse J. Phillips CM. Factors influencing women’s decisions to undergo mammography. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:744–8.

Glockner SM, Holden MG, Hilton SVW, Norcross WA. Women’s attitudes towards screening mammography. Am J Prev Med. 1992;8:69–77.

Champion VL. Compliance with guidelines for mammography screening. Cancer Detect Prev. 1992;16:253–8.

Lurie N, Slater J, McGovern P, Ekstrum J, Quam L, Margolis K. Preventive care for women: does the sex of the physician matter? N Engl J Med. 1993;329:478–82.

Osborn EH, Bird JA. McPhee SJ, Rodnick JE, Fordham D. Cancer screening by primary care physicians: can we explain the differences? J Fam Pract. 1991;32:465–71.

Hall JA, Palmer RH, Orav EJ, Hargraves JL, Wright EA, Louis TA. Performance quality, gender, and professional role: a study of physicians and nonphysicians in 16 ambulatory care practices. Med Care. 1990;28:489–501.

Becker MH (ed). The health belief model and personal health behavior. Health Educ Monogr. 1974;2:324–473.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, Attitude, Intention, and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1975.

Weinstein ND. The precaution adoption process. Health Psychol. 1988;7:355–86.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change for smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. In search of how people change: applications to addictive behaviors. Am Psychol. 1992;47:1102–14.

Velicer WF, DiClemente CC. Prochaska JO, Brandenburg N. Decisional balance measure for assessing and predicting smoking status. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1985;48:1279–89.

Burack RC, Liang J. The early detection of cancer In the primary care setting: factors associated with the acceptance and completion of recommended procedures. Prev Med. 1987;16:739–51.

American Cancer Society. Summary of current guidelines for the cancer-related check-up: recommendations. New York: American Cancer Society, 1988.

Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program Expert Panel on Detection. Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults. Arch Intern Med. 1988;148:36–69.

Mandelblatt J. Cervical cancer screening in primary care: issues and recommendations. Prim Care. 1989;16:133–55.

Eddy DM. Screening for cervical cancer. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113:214–26.

Fletcher SW, Black W. Harris R, Rimer BK, Shapiro S. Report of the International Workshop on Screening for Breast Cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:1644–56.

Maheux B. Dufort F, Beland F, Jacques A, Levesque A. Female medical practitioners: more preventive and patient-oriented? Med Care. 1988;28:87–92.

Roter D. Lipkin M. Korsgaard A. Sex differences in patients’ and physicians’ communication during primary care medical visits. Med Care. 1991;29:1083–93.

Fennema K. Meyer DL, Owen N. Sex of physician: patients’ preferences and stereotypes. J Fam Pract. 1990;30:441–6.

Bowman JA, Redman S, Dickinson JA, Gibberd R, Sanson-Fisher RW. The accuracy of Pap smear utilization self-report: a methodological consideration in cervical screening research. Health Serv Res. 1991;26:97–107.

McKenna MT, Speers M, Mallin K, Warnecke R. Agreement between patient self-reports and medical records for Pap smear histories. Am J Prev Med. 1992;8:287–91.

Sawyer JA, Earp J, Fletcher RH, Daye FF, Wynn TM. Accuracy of women’s self-report of their last Pap smear. Am J Public Health. 1989;79:1036–7.

King ES. Rimer BK. Trock B, Balsham A, Engstrom P. How valid are mammography self reports? Am J Public Health. 1990;80:1386–8.

Etzi S, Lane DS, Grimson R. The use of mammography vans by low-income women: the accuracy of self-reports. Am J Public Health. 1994;84:107–9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kreuter, M.W., Strecher, V.J., Harris, R. et al. Are patients of women physicians screened more aggressively?. J Gen Intern Med 10, 119–125 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02599664

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02599664