Abstract

Objectives

To investigate, using a nationally representative sample of preschool-aged children, the relationship among poverty history, child health, and risk of an abnormal developmental screening score.

Methods

Data were derived from the 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey and 1991 Longitudinal Follow-up. Family income in the child’s prenatal year and at 2 years old defined a poverty history for each child. Multivariate logistic regression was used to estimate the effects of poverty history on risk of an abnormal screening score or delays in large-motor, personal-social, or language subscales.

Results

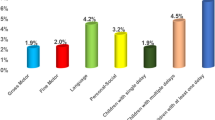

Poor and near-poor children were 1.6 to 2.0 times as likely as nonpoor children to be classified as abnormal, even when maternal and household characteristics and the child’s health history were taken into account. Preterm birth, chronic illness, dearth of reading materials in the home, and maternal depression were also associated with elevated risks of abnormal scores.

Conclusions

Poverty is the largest single predictor of an abnormal developmental screening score. The implications of inadequate medical care among poor children for the interpretation of individual screening scores and for amelioration of problems are also discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J.Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Publications; 1997.

US Department of Health and Human Services.Trends in the Well-being of America’s Children and Youth: 1996. Washington, DC: Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation; 1996.

Coiro MJ, Zill N, Bloom B. Health of our nation’s children: United States 1988.Vital and Health Statistics. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 1994. Series 10, Number 191.

Wise PL, Meyers A. Poverty and child health.Pediatr Clin North Am. 1988;35:1169–1186.

Sherman A.Wasting America’s Future: The Children’s Defense Fund Report on the Costs of Child Poverty. Boston: Beacon Press; 1994.

Frankenburg WK, Dodds J, Archer P, et al.Denver II Screening Manual. Denver, Colo: Denver Developmental Materials, Inc; 1990.

Ireton H, Thwing E.Early Childhood Development Inventory. Minneapolis, Minn: Behavior Science Systems; 1988.

Dworkin PH. Developmental screening: (still) expecting the impossible?Pediatrics. 1992;89:1221–1225.

Korenman S, Miller JE. Effects of long-term poverty on physical health of children in the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth. In: Duncan DG, Brooks-Gunn J, eds.Consequences of Growing Up Poor. New York: Russell Sage Publications; 1997.

Peterson JL, Moore KA.Motor and Social Development in Infancy: Some Results From a National Survey. Washington, DC: Child Trends, Inc.; 1987. Report no. 87-03.

Board on Children and Families, National Research Council, Institute of Medicine.Integrating Federal Statistics on Children: Report of a Workshop. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995.

Sanderson M, Placek PJ, Keppel KG. The 1988 National Maternal and Infant Health Survey: design, content and data availability.Birth. 1991;18:26–32.

US Department of Health and Human Services, National Center for Health Statistics.National Maternal and Infant Health Survey, 1988: Longitudinal Follow-up, 1991. Ann Arbor, Mich: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research; 1995.

National Center for Health Statistics.National Health Interview Survey 1981 Child Health Supplement. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 1984.

Baker PB, Keck CK, Mott FL, Quinlan SV.NLSY Handbook, Revised Edition: A Guide to the 1986–1990 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth Child Data. Columbus, Ohio: Center for Human Resource Research; 1993.

Gilbride KE. Developmental testing.Pediatr Rev.. 1995;16:338–345.

Frankenburg WK.Revised Denver Prescreening Developmental Questionnaire. Denver, Colo: Denver Developmental Materials, Inc; 1986.

National Research Council.Measuring Poverty: A New Approach. Citro CF, Michael RT, eds. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995.

United States Committee on Ways and Means.Background Material and Data on Programs Within the Jurisdiction of the Committee on Ways and Means. 109th Congress. Washington, DC: US GPO; 1996.

Radloff LS, Locke BZ. The Community Mental Health Assessment Survey and the CESD Scale. In: Weissman MM, Myers JK, Ross CE, eds.Community Surveys of Psychiatric Disorders. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1986, pp. 177–189.

Wissow LS, Gittelsohn AM, Szklo M, Starfield B, Mussman M. Poverty, race and hospitalization for childhood asthma.Am J Public Health. 1988;78:777–782.

Shah BV, Barnwell BG, Bieler GS.SUDAAN User’s Manual, Release 7.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 1996.

Ashworth K, Hill M, Walker R. Patterns of childhood poverty: new challenges for policy.J Policy Analysis Manage. 1994;13:658–80.

Miller JE.Poverty History, Race and Health at Birth Among US Children. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University; November 1997. Institute for Health, Health Care Policy and Aging Research Working Paper.

Miller JE, Korenman S. Poverty and children’s nutritional status in the United States.Am J Epidemiol. 1994;140:233–243.

Miller JE. Poverty patterns and cognitive development in the NLSY. Paper presented at: 1996 Meetings of the Population Association of America; New Orleans, May 9–11, 1996.

Bradley RH, Caldwell BM. The relation of infants’ home environments to achievement test performance in first grade: a follow-up study.Child Dev. 1984;55:803–880.

Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK, Liaw FR. The learning, physical and emotional environment of the home in the context of poverty: the Infant Health and Development Program.Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17:251–276.

Miller JE, Davis D. Poverty history, marital history and quality of children’s home environments.J Marriage Fam. 1997;59:996–1007.

Garrett P, Ng’andu N, Ferron J. Poverty experiences of young children and the quality of their home environments.Child Dev. 1994;65:331–345.

Korenman S, Miller JE, Sjaastad JE. Long-term poverty and child development in the United States: results from the NLSY.Child Youth Serv Rev. 1995;17:127–151.

Plotnick RD. Child poverty can be reduced.Future of Children: Children and Poverty. 1997;7(2):72–87.

Devaney B, Ellwood MR, Love JM. Programs that mitigate the effects of poverty on children.Future of Children: Children and Poverty. 1997;7(2):88–112.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Miller, J.E. Developmental screening scores among preschoolaged children: The roles of poverty and child health. J Urban Health 75, 135–152 (1998). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02344935

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02344935