Summary

1. This study describes the structure and functional significance of numerous song dialects in island populations of Darwin's finches from the Galápagos Archipelago.

2. The following acoustical information was obtained from tape recordings made in the islands:

-

a.

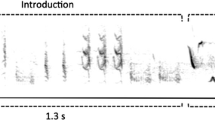

For songs: Frequency bandwidth, relative amplitude distribution according to frequency, and absolute sound pressure levels (dB).

-

b.

For the environment: Attenuation characteristics of a broadband frequency spectrum (“pink” noise) broadcast into various vegetations.

Song data are displayed graphically as frequency/amplitude histograms, and pin noise attenuation as sound transmission isopleths.

3. A comparison of modal amplitudes of song frequency spectra with mean dimensions of the vibratory (internal tympaniform) membrane of the syrinx and mean body weights, indicates that larger bodied species of Darwin's finches sing songs with peak energy at a lower frequency than do smaller bodied species.

4. A scheme is proposed that relates modal amplitude distributions and sound pressure levels of song to body size and relative abundance of species. This four-way comparison, when applied to four sympatric species of Darwin's finches on Isla Genovesa, shows that smaller species, singing songs with higher “pitched” modal amplitudes, tend to have lower sound pressure levels and occur in greater relative abundance (and possibly defend smaller territories) than larger species.

5. Song dialects ofGeospiza conirostris on islas Genovesa and Española are described and a correlation is made between the song bandwidth and the sound transmission peculiarities of their respective environments. The bandwidth is regulated by the sound attenuation characteristics of the vegetation so as to forestall the development of a frequency dependent disparity in sound pressure levels between highest and lowest song components that might be damaging to the integrity (information content) of the signal, long before it has travelled an effective communicating distance through the environment.

6. The Wolf Island environment is acoustically unique among those studied thus far in the Galápagos Archipelago because of the unusually high sound attenuation associated with the very dense vegetation. The latter causes a minimal disparity in rates of sound attenuation over unusually broad frequency spectra encompassed by the songs. The relatively high availability of foods has fostered a high population density of finches whose individual territories, when adjusted to differences in body size with conspecifics elsewhere, are, presumably, comparatively small and rendered acoustically compatable with the breeding ecology of the finches.

7. An ecoclinal shift in the song galaxy ofCamarhynchus parvulus on the south side of Isla Santa Cruz is correlated with altitudinal differences in vegetation affecting sound transmission. The narrowband song most commonly heard in the humid highlands forest is less susceptable to frequency dependent disparity in sound transmission rates than would be the case with the wideband song of the lowlands, were it sung in the discordant highlands environment. There would appear to be little if any differential advantage of wideband song over narrowband song where they occur together in the lowlands environment of Isla Santa Cruz.

8. Several cases of parallel development of song structure by sympatric species of Darwin's finches may be due to selection favoring similar vocal responses to acoustically similar “sound niches”.

Zusammenfassung

1. Die Arbeit beschreibt die Struktur und funktionelle Bedeutung zahlreicher Gesangsdialekte der Inselpopulationen bei Darwinfinken auf den Galapagos Inseln.

2. Folgende akustische Information wurde durch Tonbandaufnahmen im Freiland ermittelt:

-

a)

Bandbreite der Frequenz, der Frequenz entsprechende Schallintensität, absoluter Schalldruckpegel (dB) der Gesänge.

-

b)

Dämpfungscharakteristik des in verschiedenen Vegetationen gesendeten Breitbandspektrums eines Tongenerators.

Die Gesangsdaten sind graphisch als Frequenz/Schallintensität-Histogramme dargestellt und die Signal-Dämpfung als Isoplethen der Schallübertragung.

3. Ein Vergleich der Schallintensität der Gesangsfrequenzspektra mit Durchschnittsgrößen der Membrana tympaniformis interna in der Syrinx und mit durchschnittlichen Körpergewichten zeigt, daß größere Arten Gesänge besitzen mit der Höchstenergie in niederer Frequenz als kleinere Arten.

4. Ein Schema wird vorgeschlagen, welches Modalamplitudenverteilung und Schalldruckpegel der Gesänge mit Körpergröße und relativer Häufigkeit der Arten vergleicht. Dieser vierseitige Vergleich angewendet auf die vier zusammenlebenden Arten der Darwinfinken auf der Insel Genovesa zeigt, daß kleinere Arten, die mit Modalamplituden höherer Frequenz singen, zu niedrigerem Schalldruckpegel und zu höherer Abundanz neigen (möglicherweise auch kleinere Territorien verteidigen) als größere Arten.

5. Gesangsdialekte vonGeospiza conirostris auf den Inseln Genovesa und Española werden beschrieben; das Verhältnis zwischen Bandbreite des Gesanges und Eigenheiten der Schallübertragung ihrer jeweiligen Umgebung ist dargestellt. Die Bandbreite wird durch die von der Vegetation verursachte Dämpfungscharakteristik der Schallübertragung reguliert, um von der Frequenz abhängige Ungleichheit des Schalldruckpegels zwischen höchsten und niedrigsten Gesangsteilen zu vermeiden, der den Informationsinhalt des Signals, lange ehe es eine effektive Kommunikationsentfernung erreicht hat, beschädigen könnte.

6. Der Biotop der Insel Wolf ist akustisch einzigartig unter den bisher untersuchten Inseln im Galapagos Archipel; er weist nämlich eine von der sehr dichten Vegetation abhängende ungewöhnlich hohe Schalldämpfung auf. Die Vegetation verursacht eine minimale Ungleichheit der Schalldämpfung über das ungewöhnlich breite Frequenzspektrum der Gesänge. Die relativ reichlich vorhandene Nahrung fördert eine hohe Siedlungsdichte der Finken. Ihre Territorien bezogen auf die Körpergröße verglichen mit Artgenossen auf anderen Inseln sind wahrscheinlich verhältnismäßig klein und akustisch der Brutökologie der Finken angepaßt.

7. Eine ökologische Verschiebung der Gesangscharakteristik vonCamarhynchus parvulus im S der Insel Santa Cruz ist korreliert mit Höhenunterschieden in der Vegetation, die die Schallübertragung beeinflußt. Gesänge mit enger Bandbreite, die man gewöhnlich in den feuchten Höhenwäldern hört, sind weniger empfindlich gegen von Frequenz abhängige Ungleichheiten der Schallübertragung als die Breitbandgesänge des Tieflandes, wenn sie in der nicht passenden Hochlandumgebung gesungen würden. Ein möglicher kleiner Vorteil von Breitbandgesängen gegenüber Schmalbandgesängen spielt scheinbar keine Rolle in der Tieflandumgebung von Santa Cruz, wo beide Typen zusammen vorkommen.

8. Mehrere Fälle paralleler Entwicklung von Gesangstrukturen zusammenlebender Arten der Darwinfinken könnten durch Selektion verursacht worden sein, die ähnliche Stimmreaktionen in akustisch ähnlichen „Gesangsnischen“ begünstigt.

Similar content being viewed by others

Literature

Abbott, I., L. K. Abbott &P. R. Grant (1977): Comparative ecology of Galápagos ground finches (Geospiza Gould): evaluation of the importance of floristic diversity and interspecific competition. Ecol. Monogr. 47: 151–184.

Baptista, L. F. (1975): Song dialects and demes in sedentary populations of the white-crowned sparrow (Zonotrichia leucophrys nuttalli). Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 105: 1–52.

Beebe, W. (1924): Galapagos: world's end. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York.

Ditto (1926): The Arcturus adventure. G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York.

Bergmann, H.-H. (1976): Konstitutionsbedingte Merkmale in Gesängen und Rufen europäischer Grasmücken (Gattung:Sylvia). Z. Tierpsychol. 42: 315–329.

Billeb, S. L. (1968): Song variation in three island populations of Galápagos warbler finch (Certhidea olivacea Gould). M. A. thesis, San Francisco State University.

Brown, W. L. &E. O. Wilson (1956): Character displacement. Syst. Zool. 5: 49–64.

Bowman, R. I. (1961): Morphological differentiation and adaptation in the Galápagos finches. Univ. Calif. Publ. Zool. 58: 1–302.

Ditto (1963): Evolutionary patterns in Darwin's finches. Occas. Papers Calif. Acad. Sci. 44: 107–140.

Ditto (1980): The evolution of song in Darwin's finches. InBowman, R. I. &A. E. Leviton (Eds.): Patterns of evolution in Galápagos organism. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Pac. Div., San Francisco.

Chapman, F. M. (1940): The post-glacial history ofZonotrichia capensis. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 77: 381–438.

Chappuis, C. (1971): Un example de l'influence du milieu sur les emission vocales des oiseaux: l'evolution des chants en foret equatoriale. Terre et Vie 25: 183–202.

Cody, M. L. (1969): Convergent characteristics in sympatric species: a possible relation to interspecific competition and aggression. Condor 71: 222–239.

Ditto (1973): Character displacement. Ann. Rev. Syst. Ecol. 4: 189–201.

Ditto (1974): Competition and the structure of bird communities. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton.

Ditto &J. H. Brown (1970): Character convergence in Mexican finches. Evolution 24: 304–310.

Curio, E. &P. Kramer (1965):Geospiza conirostris auf Abingdon und Wenman entdeckt. J. Orn. 106: 355–357.

Cutler, B. D. (1970): Anatomical studies on the syrinx of Darwin's finches. M. A. thesis, San Francisco State University.

Dooling, R. J., J. A. Mulligan &J. D. Miller (1971): Auditory sensitivity and song spectrum on the common canary (Serinus canarius). J. Acoust. Soc. Amer. 50: 700–709.

Gifford, W. E. (1919): Field notes on the land birds of the Galápagos Islands and of Cocos Island, Costa Rica. Proc. Calif. Acad. Sci. 2: 189–258.

Grant, P. R. (1966): The coexistence of two wren species of the genusThryothorus. Wilson Bull. 78: 266–278.

Greenewalt, C. H. (1968): Bird song: acoustics and physiology. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D. C.

Grimes, L. G. (1974): Dialects and geographical variation in the song of the splendid sunbirdNectarinia coccinigaster. Ibis 116: 314–329.

Gulledge, J. L. (1970): An analysis of song in the mockingbird generaNesomimus andMimus. M. A. thesis, San Francisco State University.

Harris, M. A. &R. R. Lemon (1972): Songs of song sparrows (Melospiza melodia); individual variation and dialects. Can. J. Zool. 50: 301–309.

Heuwinkel, H. (1978): Der Gesang des Teichrohrsängers (Acrocephalus scirpaceus) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung der Schalldruckpegel (“Lautstärke”-) Verhältnisse. J. Orn. 119: 450–461.

Hope, S. (1976): Determinants of form in vocalizations of the Steller's jay. M. A. thesis, San Francisco State University.

Ingård, U. (1953): A review of the influence of meteorological conditions on sound propagation. J. Acoust. Soc. Amer. 25: 405–411.

Jilka, A. &B. Leisler (1974): Die Einpassung dreier Rohrsängerarten (Acrocephalus schoenobaenus, A. scirpaceus, A. arundinaceus) in ihre Lebensräume in bezug auf das Frequenzspektrum ihrer Reviergesänge. J. Orn. 115: 192–212.

Jo, N. (1979): Karyotypic analysis of Darwin's finches. InBowman, R. I. &A. E. Leviton (Eds.): Patterns of evolution in Galápagos organisms. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Pac. Div., San Francisco.

King, J. R. (1972): Variation in the song of the rufous-collared sparrow,Zonotrichia capensis, in northwestern Argentina. Z. Tierpsychol. 25: 155–169.

Konishi, M. (1970 a): Comparative neurophysiological studies of hearing and vocalizations in songbirds. Z. vergl. Physiol. 66: 257–272.

Ditto (1970 b): Evolution of design features in the coding of species-specificity. Amer. Zool. 10: 67–72.

Ditto (1973): Locatable and nonlocatable acoustic signals for barn owls. Amer. Nat. 107: 775–785.

Lack, D. (1945): The Galápagos finches (Geospizinae): a study in variation. Occas. Papers Calif. Acad. Sci. 21: 1–152.

Ditto &H. N. Southern (1949): Birds of Tenerife. Ibis 91: 607–626.

Lanyon, W. E. (1967): Revision and probable evolution of theMyiarchus flycatchers of the West Indies. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 136: 329–370.

Ditto (1978): Revision of theMyiarchus flycatchers of South America. Bull. Amer. Mus. Nat. Hist. 161: 427–628.

Lemon, R. E. (1971): Differentiation of song dialects in cardinals. Ibis 113: 373–377.

Ditto (1975): How birds develop song dialects. Condor 77: 385–406.

Marler, P. (1955): Characteristics of some animal calls. Nature 176: 6–8.

Ditto (1960): Bird song and mate selection. InLanyon, W. E. &W. N. Tavolga (Eds.): Animal sounds and Communication. Amer. Inst. Biol. Sci. Publ. 7: 348–367.

Ditto (1970): A comparative approach to vocal learning. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. Monogr. 71: 1–25.

Marler, P. &D. J. Boatman (1951): Observations on the birds of Pico, Azores. Ibis 93: 90–9.

Ditto &M. Tamura (1962): Song “dialects” in three populations of white-crowned sparrows. Condor 64: 367–377.

Marten, K. &P. Marler (1977): Sound transmission and its significance for animal vocalization. I. Temperate habitats. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2: 271–290.

Ditto,D. Quine &P. Marler (1977): Sound transmission and its significance for animal vocalization. II. Tropical forest habitats. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 2: 291–302.

Mayr, E. (1942): Systematics and the origin of species. Columbia Univ. Press, New York.

Mirksy, E. N. (1976): Song divergence in humingbird and junco populations on Guadalupe Island. Condor 78: 230–235.

Morton, E. S. (1975): Ecological sources of selection on avian sounds. Amer. Nat. 109: 17–34.

Nottebohm, F. (1972): The origin of vocal learning. Amer. Nat. 106: 116–140.

Ditto (1975): Continental patterns of song variability inZonotrichia capensis: some possible ecological correlates. Amer. Nat. 109: 605–624.

Orejuela, J. E. &M. L. Morton (1975): Song dialects in several populations of mountain white-crowned sparrows (Zonotrichia leucophrys oriantha) in the Sierra Nevada. Condor 77: 145–153.

Peterson, A. P. G. &E. E. Gross (1972): Handbook of noise measurement, 7th edition. General Radio Company, Concord, Mass.

Polans, N. O. (1980): Enzyme polymorphisms in Galápagos finches. InBowman, R. I. &A. E. Leviton (Eds.): Patterns of evolution in Galápagos organism. Amer. Assoc. Adv. Sci. Pac. Div., San Francisco.

Rothschild, W. &E. Hartert (1899): A review of the ornithology of the Galapagos Islands. With notes on the Webster-Harris expedition. Novit. Zool. 6: 85–205.

Ditto (1902): Further notes on the fauna of the Galapagos Islands. Novit. Zool. 9: 373–418.

Simkin, G. (1973): Z. Zhurn. 52: 1261–1263.

Snodgrass, R. E. &E. Heller (1904): Papers from the Hopkins-Stanford Galapagos expedition, 1898–1899. XVI. Birds. Proc. Wash. Acad. Sci. 5: 231–372.

Thielcke, G. (1965): Gesangsgeographische Variation des Gartenbaumläufers (Certhia brachydactyla) im Hinblick auf das Artbildungs-problem. Z. Tierpsychol. 22: 542–566.

Ditto (1969): Geographic variation in bird vocalizations. InR. A. Hinde (Ed.): Bird vocalizations, 311–339. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

Ward, W. V. (1964): The songs of the apapane. Living Bird 3: 97–117.

Welty, J. C. (1975): The life of birds. 2nd ed. Saunders, Philadelphia.

Witkin, S. R. (1977): The importance of directional sound radiation in avian vocalization. Condor 79: 490–493.

Wilson, G. P. (1968): Instruction book for Galápagos Islands project: acoustical measuring equipment. Wilson, Ihrig & Assoc., Oakland, California.

Wood, A. (1947): Acoustics. Interscience Publishers, Inc., New York.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Contribution No. 231 of the Charles Darwin Research Station, Galapagos.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bowman, R.I. Adaptive morphology of song dialects in Darwin's finches. J Ornithol 120, 353–389 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01642911

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01642911