Abstract

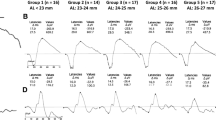

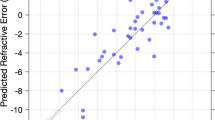

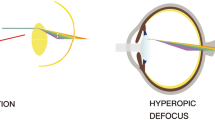

The very common ocular clinical ocular condition in children juvenile onset myopia results from axial elongation of the eye. In humans, some studies have found an association of myopia with greater levels of nearpoint activity and with differences in accommodation and convergence function. This paper reviews a variety of laboratory and clinical studies which are consistent with the hypothesis that retinal image defocus is biochemically transformed into an axial elongation expressed through increased posterior segment growth, and thus myopia. This paper also reviews theories of emmetropization, and classifies them as correlational, feedback, and combination. Evidence is presented to suggest that a combination theory, which combines both correlation of the ocular dioptric components and some feedback mechanism for growth of the eye, is the most correct. Current laboratory research suggests that quality and/or focus (defocus) of retinal imagery is involved in this feedback mechanism and that experimentally induced myopia might be enhanced, reduced or eliminated by pharmaceutical application. Direction of defocus may affect the rate of posterior segment growth, and thus the rate of ocular axial elongation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sperduto RD, Seigel D, Roberts J, Rowland M. Prevalence of myopia in the United States. Arch Ophthalmol 1983; 101: 405–7.

Grosvenor T. A review and suggested classification system for myopia on the basis of agerelated prevalence and age of onset. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 545–54.

Hirsch MJ. The changes in refraction between, the ages of 5 and 14-theoretical and practical considerations. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1952; 29: 445–59.

Young FA, Beattie RJ, Newby FJ, Swindal MT. The Pullman study-a visual survey of Pullman school children. Part II. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1954; 31: 192–203.

Langer MA. Changes in ocular refraction from ages 5–16. MS thesis. Indiana Univ, 1966.

Goss DA. Childhood myopia.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991: 81–103.

Roberts WL, Banford RD. Evaluation of bifocal correction technique in juvenile myopia. Optom Weekly 1967: 58(38): 25–8, 31; 58(39): 21–20: 58(40): 23–8: 58(41): 27–34: 58(34): 19–24, 26.

Baldwin WR, West D, Jolley J, Reid W. Effects of contact lenses on refractive corneal and axial length changes in young myopes. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1969; 46: 903–11.

Goss DA, Cox VD. Trends in the change of clinical refractive error in myopia progression. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 56: 608–13.

Grosvenor T, Perrigin DM, Perrigin J, Maslovitz B. Houston myopia control study: a randomized clinical trial. Part II. Final report by the patient care team. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 482–98.

Goss DA. Variables related to the rate of childhood myopia progression. Optom Vis Sci 1990; 67: 631–6.

Perrigin J, Perrigin D, Quintero S, Grosvenor T. Silicone-acrylate contact lenses for myopia control: 3-year results. Optom Vis Sci 1990; 67: 764–9.

Mäntyjärvi MI. Changes of refraction in school children. Arch Ophthalmol 1985; 103: 790–2.

Goss DA. Linearity of refractive change with age in childhood myopia progression. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 775–80.

Septon RD. Myopia among optometry students. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1984; 61: 745–51.

Working Group on Myopia Prevalence and Progression, National Research Council Committee on Vision. Myopia: Prevalence and Progression. Washington: National Academy Press, 1989.

Goss DA, Winkler RL. Progression of myopia in youth: age of cessation: Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1983; 60: 651–8.

Goss DA, Erickson P, Cox VD. Prevalence and pattern of adult myopia progression in a general optometric practice population. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 62: 470–7.

Goss DA, Erickson P. Meridional corneal components of myopia progression in young adults and children. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 475–81.

Baldwin WR, Adams AJ, Flattau P. Young-adult myopia.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Application. Boston: Butterworth-Heinernann, 1991: 104–20.

Zadnik K. Mutti DO. Refractive error changes in law students. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 558–61.

Erickson P. Optical components contributing to refractive anomalies.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991: 199–218.

Goss DA, Erickson P. Effects of changes in anterior chamber depth on refractive error of the human eye. Clin Vis Sci 1990; 5: 197–201.

Stenstrom S. Investigation of the variation and correlation of the optical elements of human eyes-Part V. Woolf D, translator. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1948; 25: 438–49.

Stenstrom S. Investigation of the variation and the correlation of the optical elements of human eyes - Part III. Woolf D, translator. Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1948; 25: 340–50.

Ohno S. An analytical study on correlation of refractivity to ocular axial length in adolescents viewed by means of roentgen-vision. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn 1956; 60: 460–81.

van Alphen GWHM. On emmetropia and ametropia. Ophthalmologica 1961: 142(supplementum): 1–92.

Araki M. Studies on refractive components of human eye by means of ultrasonic echogram. Report III: The correlation of among refractive components. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn 1962; 66: 128–47.

Sorsby A, Benjamin B, Sheridan M. Refraction and its Components During the Growth of the Eye from the Age of Three. Medical Research Council Special Report Series No. 301. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1961.

Sorsby A, Leary GA. A Longitudinal Study of Refraction and its Components During Growth. Medical Research Council Special Report Series No. 309. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1970.

Sorsby A. Biology of the eye as an optical system.In: Safir A, ed. Refraction and Clinical Optics. Hagerstown Md: Harper and Row, 1980: 133–49.

Tokoro T, Kabe S. Relation between changes in the ocular refraction and refractive components and development of the myopia. Acta Soc Ophthalmol Jpn 1964; 68: 1240–53.

Tokoro T, Suzuki K. Changes in ocular refractive components and development of myopia during seven years. Jpn J Ophthalmol 1969; 13: 27–34.

Goss DA, Cox VD, Herrin-Lawson GA, Nielsen ED, Dolton WA. Refractive error, axial length, and height as a function of age in young myopes. Optom Vis Sci 1990; 67: 332–8.

Fledelius HC. Changes in refraction and eye size during adolescence-with special reference to the influence of low birth weight.In: Fledelius HC, Alsbirk PH, Goldschmidt E, eds. Third International Conference on Myopia. The Hague: Junk. Doc Ophthalmol Proc Series 1981; 28: 63–9.

Fledelius HC. Ophthalmic changes from age of 10 to 18 years. A longitudinal study of sequels to low birth weight. III. Ultrasound oculometry and keratometry of anterior eye segment. Acta Ophthalmologica 1982; 60: 393–402.

Raviola E, Wiesel TN. Effect of dark-rearing on experimental myopia in monkeys. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1978; 17: 485–8.

Wiesel TN, Raviola E. Increase in axial length of the macaque monkey eye after corneal opacification. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1979: 18: 1232–6.

McKanna JA, Casagrande VA. Zonular displasia in myopia.In: Sato T, Yamaji R, eds.. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Myopia. Yokohama-shi, Japan: Sato Eye Clinic, 1981: 21–32.

Wallman J, Adams JI, Trachtman JN. The eyes of young chickens grow toward emmetropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981; 20: 557–61.

Goss DA, Criswell MH. Myopia development in experimental animals - A literature review: Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1981; 58: 859–69.

Criswell MH, Goss DA. Myopia development in nonhuman primates - A literature review. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1983; 60: 250–68.

Yinon U. Myopia induction in animals following alteration of the visual input during development: A review. Curr Eye Res 1984; 3: 677–90.

Raviola E, Wiesel TN. An animal model of myopia. New Eng J Med 1985; 312: 1609–15.

Smith EL III, Harwerth RS, Crawford MLJ, von Noorden GK. Observations on the effects of form deprivation on the refractive status of the monkey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1987; 28: 1236–45.

Wallman J, Gottlieb MD, Rajaram V, Fugate-Wentzek LA. Local retinal regions control local eye growth and myopia. Science 1987; 23: 73–7.

Wallman J, Adams JI. Developmental aspects of experimental myopia in chicks: Susceptibility recovery and relation to emmetropization. Vision Res 1987; 27: 1139–63.

Seltner RL, Sivak JG. Experimentally induced myopia in chicks. Can J Optom 1988; 50: 190–3.

Holden AL, Hodos W, Hayes BP, Fitzke FW. Myopia: induced, normal and clinical. Eye 1988; 2: S242–56.

Sivak JG, Barrie DL, Callender MG, Doughty MJ, Seltner RL, West JA. Optical causes of experimental myopia.In: Bock GR, Widdows K, eds. Myopia and the Control of Eye Growth. Ciba Foundation Symposium 155. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, 1990: 160–72.

Norton TT. Experimental myopia in three shrews.In: Bock GR, Widdows K, eds. Myopia and the Control of the Eye Growth. Ciba Foundation Symposium 155. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, 1990: 178–94.

Hodos W, Holden AL, Fitzke FW, Hayes BP, Low JC. Normal and induced myopia in birds: models for human vision.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991: 235–45.

Troilo D, Judge SJ. Ocular development and visual deprivation myopia in the common marmoset (Callithrix jacchus). Vis Res 1993; 33: 131–24.

Robb RM. Refractive errors associated with hemangiomas of the eyelids and orbit in infancy. Am J Ophthalmol 1977; 83: 52–8.

O'Leary DJ, Millodot M. Eyelid closure causes myopia in humans. Experentia 1979; 35: 1478–9.

Hoyt CS, Stone RD, Fromer C, Billson FA. Monocular axial myopia associated with neonatal eyelid closure in human infants. Am J Ophthalmol 1981; 91: 197–200.

Rabin J, van Sluyters RC, Malach R. Emmetropization: A vision-dependent phenomenon. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981; 20: 561–4.

Fledelius HC. Myopia of prematurity-changes during adolescence - A longitudinal study including ultrasound oculometry.In: Thijssen JM, Verbeek AM, eds. Ultrasonography in Ophthalmology - Proceedings of the 8th SIDUO Congress. The Hague: Junk. Doc Ophthalmol Proc Series 1981; 29: 217–23.

Goss DA. Refractive status and premature birth. Optom Monthly 1985; 76: 109–11.

Nathan J, Kiely PM, Crewther SG, Crewther DP. Disease-associated visual image degradation and spherical refractive errors in children. Am. J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 62: 680–8.

Miller-Meeks MJ, Bennett SR, Keech RV, Blodi CF. Myopia induced by vitreous hemorrhage. Am J Ophthalmol 1990; 109: 199–203.

Gee SS, Tabbara KF. Increase in ocular axial length in patients with corneal opacification. Ophthalmol 1988; 95: 1276–8.

Rasooly R, BenEzra D. Congenital and traumatic; cataract-the effect on ocular axial length. Arch Ophthalmol 1988; 106: 1066–8.

Smith EL III, Maguire GW, Watson JT. Axial lengths and refractive errors in kittens reared with an optically induced anisometropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1980; 19: 1250–5.

Ni J, Smith EL III. Effects of chronic optical defocus on the kitten's refractive status. Vision Res 1989; 29: 929–38.

Schaeffel F, Glasser A, Howland HC. Accommodation, refractive error, and eye growth in chickens. Vis Res 1988; 28: 639–57.

Schaeffel F, Troilo D, Wallman J, Howland HC. Developing eyes that lack accommodation grow to compensate for imposed defocus. Vis Neurosci 1990; 4: 177–83.

Schaeffel F, Howland HC. Properties of the feedback loops controlling eye growth and refractive state in the chicken. Vis Res 1991; 31: 717–34.

Irving EL, Callender MG, Sivak JG. Inducing myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism in chicks. Optom Vis Sci 1991; 68: 364–8.

Irving EL, Sivak JG, Callender MG. Refractive plasticity of the developing chick eye. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1992; 12: 448–56.

Troilo DB. The Visual Control of Eye Growth in Chicks. Ph.D. Dissertation. City University of New York, 1989.

Troilo D. Experimental studies of emmetropization in the chick.In: Bock GR, Widdows K, eds. Myopia and the Control of Eye Growth. Ciba Foundation Symposium 155. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, 1991: 89–102.

Troilo D, Wallman J. The regulation of eye growth and refractive state: an experimental study of emmetropization. Vis Res 1991; 31: 1237–50.

Smith EL III, Harwerth RS, Crawford MLJ. Spatial contrast sensitivity defects in monkeys produced by optically induced anisometropia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1985; 26: 330–42.

Smith EL III, Harwerth RS, Duncan GS, Crawford MLJ. A comparison of the spectral sensitivities of monkeys with anisometropic and stimulus deprivation amblyopia. Behav Brain Res 1986; 22: 13–24.

Hodos W, Erichsen JT. Lower-field myopia in birds: an adaptation that keeps the ground in focus. Vis Res 1990; 30: 653–7.

Sivak JG. Optical adaptations of the vertebrate eye.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991: 219–34.

McBrien NA, Moghaddam HO, Reeder AP, Moules S. Structural and biochemcial changes in the sclera of experimentally myopic eyes. Biochem Soc Trans 1991; 19: 861–5.

Gottlieb MD, Himanshu BJ, Nickla DL. Scleral changes in chicks with form-deprivation myopia. Curr Eye Res 1990; 9: 1157–65.

Christensen AM, Wallman J. Evidence that increased scleral growth underlies visual deprivation myopia in chicks. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1991; 32: 2143–50.

Rada JA, Throft RA, Hassell JR. Increased aggrecan (cartilage proteoglycan) production in the sclera of myopic chicks. Develop Biol 1991; 147: 303–12.

Funata M, Tokoro T. Scleral change in experimentally myopic monkeys. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 1990; 228: 174–9.

Curtin BJ, Teng CC. Scleral changes in pathological myopia. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol 1957; 62: 777–90.

McKusick VA. Mendelian Inheritance in Man 8th ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Press, 1988.

Goss DA, Hampton MJ, Wickham MG. Selected review on genetic factors in myopia. J Am Optom Assoc 1988; 59: 875–84.

Shapiro MB, France TD. The ocular features of Down's syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol 1985; 99: 659–63.

Woodhouse JM, Meades JS, Leat SJ, Saunders KJ. Reduced accommodation in children with Down syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993; 34: 2382–7.

Munoz EA, Ponce ME, Ramos R, Bernal G, Jimenez JM. Refractive errors in inherited retinal diseases in Hispanic population. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33: 1074.

Brecha N. Retinal neurotransmitters: histochemical and biochemical studies.In: Emson PC, ed. Chemical Neuroanatomy. New York: Raven Press, 1983: 85–129.

Dowling JE. The Retina-An Approachable Part of the Brain. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1987: 133–63.

Daw NW, Brunken WJ, Parkinson D. The function of synaptic transmitters in the retina. Ann Rev Neurosci 1989; 12: 205–25.

Vessey GA, Brennan NA, Barrington M, Kalloniatis M, Squires MA, Naplper GA, Vingrys AJ. Retinal morphological changes and altered eye growth induced by low dose kainic acid. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33: 711.

Redburn DA. Co-transmitter roles of melatonin and glutamate in the outer plexiform layer of mammalian retina.In: Redburn DA, Pasantes-Morales H, eds. Extracellular and Intracellular Messengers in the Vertebrate Retina. New York: Liss, 1989: 191–205.

Kleine TO. Biosynthesis of proteoglycans: an approach to locate it in different membrane systems.In: Hall DA, Jackson DS, eds. International Review of Connective Tissue Research., Vol 9. New York: Academic Press, 1981: 27–98.

Qiao X, Yang X-L, Noebels JL, Wu SM. Modulatory roles of endogenous zinc at photoreceptor output synapses in the vertebrate retina. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1992; 33: 1409.

Smith EL, Fox DA, Duncan GC. Refractive-error changes in kitten eyes produced by chronic; ON-channel blockade. Vision Res 1991; 31: 833–44.

Iuvone PM, Tigges M, Stone RA, Lambert S, Laties AM. Effects of apomorphine, a dopamine: receptor agonist, on ocular refraction and axial elongation in a primate model of myopia. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1991; 32: 1674–7.

Stone RA, Lin T, Laties AM, Iuvone PM. Retinal dopamine and form-deprivation myopia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1989; 86: 704–6.

Oishi T, Lauber JK. Chicks blinded with formoguanamine do not develop lid suture myopia. Curr Eye Res 1988; 7: 69–73.

Dvorak DR, Morgan IG. Intravitreal kainic acid permanently eliminates off pathways from chick retina. Neurosci Lett 1983; 36: 249–53.

Ingham CA, Morgan IG. Dose-dependent effects of intravitreal kainic acid on specific cell types in chicken retina. Neurosci 1983; 9: 165–81.

Wildsoet CF, Pettigrew JD. Kainic acid-induced eye enlargement in chickens: differential effects on anterior and posterior segments. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1988; 29: 311–9.

Iuvone PM, Tigges M, Fernandes A, Tigges J. Dopamine synthesis and metabolism in rhesus monkey retina: Development, aging and the effects of monocular visual deprivation. Visual Neurosci 1989; 2: 465–71.

Li XX, Schaeffel F. Kohler K, Zrenner E. Dose-dependent effects of 6-hydroxy dopamine on deprivation myopia, electroretinograms, and dopaminergic amacrine cells in chickens. Visual Neurosci 1992; 9: 483–92.

Laties AM, Stone RA. Some visual and neurochemical correlates of refractive development. Vis Neurosci 1991; 7: 125–8.

McBrien NA, Moghaddam HO, Reeder AP. Atropine reduces experimental myopia and eye enlargement via a nonaccommodative mechanism. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993; 34: 205–15.

Crewther DP, Crewther SG, Cleland BG. Is the retina sensitive to the effects of prolonged blur? Exp Brain Res 1985; 58: 427–34.

Crewther DP, Crewther SG. Pharmacological modification of eye growth in normally reared and visually deprived chicks. Curr Eye Res 1990; 9: 733–40.

Lampl M, Veldhuis JD, Johnson ML. Saltation and stasis: a model of human growth. Science 1992; 258: 801–3.

Noden DM. An analysis of the migratory behavior of avian cephalic neural crest cells. Dev Biol 1975; 42: 106–30.

Noden DM. Periocular mesenchyme: neural crest and mesodermal interactions.In: Jacobiec FA, ed. Ocular Anatomy, Embryology and Teratology. Philadelphia: Harper and Row, 1982: 97–119.

Gospodarowicz D, Giguere L. Growth factors, effect on corneal tissue.In: McDevitt DS, ed. Cell Biology of the Eye. New York: Academic Press, 1982: 98–142.

Gospodarowicz D. Fibroblast growth factor.In: Guroff G, ed. Growth and Maturation Factors, Vol 3. New York: Wyly Press, 1985: 1–36.

Thoenen H, Edgar D. Neurotrophic factors. Science 1986; 229: 238–42.

Stone RA, Laties AM, Raviola E, Wiesel TN. Increase in retinal vasoactive intestinal polypeptide after eyelid fusion in primates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988; 85: 257–60.

Waldbillig RJ, Arnold DR, Fletcher RT, Chader GJ. Insulin and IGF-1 binding in chick sclera. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1990; 31: 1015–22.

Folkman J, Merler E, Abernath C, Williams G, Isolation of a tumor factor responsible for angiogenesis. J Exp Med 1971; 133: 275–81.

Maddock RJ, Millodot M, Leat S, Johnson CA. Accommodation response and refractive error. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1981; 20: 387–91.

Smith G. The accommodative resting states, instrument accommodation and their measurement. Optica Acta 1983; 30: 347–59.

Bullimore MA, Boyd T, Mather HE, Gilmartin B. Near retinosco and refractive error. Clin Exp Optom 1988; 71: 114–8.

McBrien NA, Millodot M. The effects of refractive error on the accommodative response gradient. Ophthal Physiol Opt 1986; 6: 145–9.

Rosenfield M, Gilmartin B. Synkinesis of accommodation and vergence in late-onset myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1987; 64: 929–37.

Rosner J, Rosner J. Relation between clinically measured tonic accommodation and refractive status in 6- to 14-year-old children. Optom Vis Sci 1989; 66: 436–9.

Zhai HF, Guang ZS. Observation of accommodation in juvenile myopia. Eye Science (China) 1988; 4: 228–31.

Goss DA. Attempts to reduce the rate of increase of myopia in young people - a critical literature review. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1982; 59: 828–41.

Young FA, Leary GA, Grosvenor T, Maslovitz B, Perrigin DM, Perrigin J, Quintero S. Houston myopia control study: a randomized clinical trial. Part I. Background and design of the study. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1985; 62: 605–13.

Curtin BJ. The Myopias: Basic Science and Clinical Management. Philadelphia: Harper & Row, 1985: 219–21.

Goss DA, Eskridge JB. Myopia.In: Amos JF, ed. Diagnosis and Management in Vision Care. Boston: Butterworths, 1987: 121–71.

Grosvenor TP. Primary Care Optometry, 2nd ed. New York: Professional Press, 1989: 81–3.

Grosvenor TP. Myopia: What can we do about it clinically? Optom Vis Sci 1989; 66: 415–9.

Goss DA. Effect of bifocal lenses on the rate of childhood myopia progression. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1986; 63: 135–41.

Goss DA, Shewey WB. Rates of childhood myopia progression as a function of type of astigmatism. Clin Exp Optom 1990; 73: 159–63.

Goss DA, Grosvenor T. Rates of childhood myopia progression with bifocals as a function of nearpoint phoria: consistency of three studies. Optom Vis Sci 1990; 67: 637–40.

Avetisov ES. Unterlagen zur Entstehungstheorie der Myopie. 1. Mitteilung. Die Rolle der Accommodation in der Entstehung der Myopie. Klin Mbl Augenheilk 1979; 175: 735–40.

Avetisov ES. Unterlagen zur Entstehungstheorie der Myopie. 4. Mitteilung. Entstenhung der Myopie und einige neue Moglichkeiten zu ihrer Prophylaxe und Therapie. Klin Mbl Augenheilk 1986; 176: 911–4.

Birnbaum MH. Management of the low myopia pediatric patient. J Am Optom Assoc 1979; 50: 1281–9.

Birnbaum MH. Clinical management of myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1981; 58: 554–9.

Goss DA. Clinical accommodation and heterophoria findings preceding juvenile onset of myopia. Optom Vis Sci 1991; 68: 110–6.

Baldwin WR. Some relationships between ocular, anthropometric, and refractive variables in myopia. PhD Thesis. Indiana Univ, 1964.

Goldschmidt E. On the etiology of myopia. Acta Ophthalmol 1968; 98 (supplement): 1–72.

Borish IM. Clinical Refraction, 3rd ed. Chicago; Professional Press, 1970: 83–114.

Grosvenor T. Are visual anomalies related to reading ability? J Am Optom Assoc 1977; 48: 510–6.

Angle J, Wissman DA. Age, reading and myopia. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1967; 55: 302–8.

Richler A, Bear JC. Refraction, nearwork, and education- a population study in Newfoundland. Acta Ophthalmol 1980; 58: 468–78.

Bear JC, Richler A, Burke G. Nearwork and familiar resemblances in ocular refraction: a population study in Newfoundland. Clin Genet 1981; 19: 462–72.

Baldwin WR. A review of statistical studies of relations between myopia and ethnic, behavioral, and physiological characteristics. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1981; 58: 516–27.

Curtin BJ. The Myopias: Basic Science and Clinical Management. Philadelphia: Harper & Row, 1985: 61–151.

Grosvenor TP. Primary Care Optometry, 2nd ed. New York: Professional Press, 1989: 51–2.

Bear JC. Epidemiology and genetics of refractive anomalies.In: Grosvenor T, Flom MC, eds. Refractive Anomalies: Research and Clinical Applications. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1991: 57–80.

Pärssinen O, Hemminki E, Klemetti A. Effect of spectacle use and accommodation on myopic progression: final results of a three-year randomized clinical trial among school children. Br J Ophthalmol 1989; 73: 547–51.

Pärssinen O, Lyyra AL. Myopia and myopic progression among school children: a three-year follow-up study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1993: 34: 2794–802.

Ciuffreda KJ, Kenyon RV. Accommodative vergence and accommodation in normals amblyopes, and strabismic.In: Schor CM, Ciuffreda KJ, eds. Vergence Eye Movements: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Boston: Butterworths, 1983: 101–73.

Ward PA. A review of some factors affecting accommodation. Clin Exp Optom 1987; 70: 23–32.

Rouse MW, London R, Allen DC. An evaluation of the monocular estimate method of dynamic retinoscopy. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1982; 59: 234–9.

Cooper J. Accommodative dysfunctions.In: Amos JF, ed. Diagnosis and Management in Vision Care. Boston: Butterworths, 1987: 431–54.

Locke LC, Somers W. A comparison study of dynamic retinoscopy techniques. Optom Vis Sci 1989; 66: 540–4.

Jackson TW, Goss DA. Variation and correlation of clinical tests of accommodative function in a sample of school-age children. J Am Optom Assoc 1991; 62: 857–66.

Jacobs RJ, Smith G, Chan CDC. Effect of defocus on blur thresholds and on thresholds of perceived change in blur: comparison of source and observer methods. Optom Vis Sci 1989; 66: 545–53.

Cline D, Hofstetter HW, Griffin JR, eds. Dictionary of Visual Science 3rd ed. Radnor, PA: Chilton, 1980: 21.

Duke-Elder S, Abrams D. Ophthalmic Optics and Refraction.In: Duke-Elder S, ed. System of Ophthalmology, V. St. Louis: Mosby, 1970: 247.

Everson RW. Age variation in refractive error distributions. Optom Weekly 1973; 64: 31–4.

Sorsby A, Benjamin B, Davey JB, Sheridan M, Tanner JM. Emmetropia and its Aberrations. Medical Research Council Special Report Series No 293. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1957.

Francois J, Goes F. Ultrasonographic study of 100 emmetropic eyes. Ophthalmologica 1977: 175: 321–7.

Larsen JS. Axial length of the emmetropic eye and its relation to the head size. Acta Ophthalmol 1979; 57: 76–83.

Hofstetter HW. Emmetropization - Biological process or mathematical artifact? Am J Optom Arch Am Acad Optom 1969; 46: 447–50.

Gernet H, Olbrich E. Excess of the human refraction curve and its cause.In: Gitter HA, Keeney, Sarin AH, Meyer LK, eds. Ophthalmic Ultrasound-Proceedings of the Fourth International Congress of Ultrasonography in Ophthalmology. St. Louis: Mosby, 1969: 142–8.

Mark HH. Emmetropization - Physical aspects of a statistical phenomenon. Ann Ophthalmol 1972; 4: 398–401.

van Alphen GWHM. Choroidal stress and emmetropization. Vision Res; 1986; 26: 723–34.

Wickham MG. Growth as a factor in the etiology juvenile-onset myopia.In: Goss DA, Edmondson LL, Bezan DJ, eds. Proceedings of the 1986 NSU Symposium on Theoretical and Clinical Optometry. Tahlequah, OK: Northeastern State University, 1986: 117–37.

Medina A. A model for emmetropization: Predicting the progression of ametropia. Ophthalmologica 1987; 194: 133–9.

Goss DA. Retinal-image mediated ocular growth as a possible etiological factor in juvenile-onset myopia.In: Vision Science Symposium/A Tribute to Gordon G. Heath. Bloomington: Indiana Univ, 1988: 165–83.

Medina A, Fariza E. Emmetropization as a first-order feedback system. Vis Res 1993; 33: 21–6.

Berck RR. An examination of refractive error through computer simulation. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1983; 60: 67–73.

Stenstrom S. Variations and correlations of the optical components of the eye.In: Sorsby A, ed. Modern Trends in Ophthalmology Vol II. New York: Paul B. Hoeber, 1947: 87–102.

Carroll JP. Geometrical optics and the statistical analysis of refractive error. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1980; 57: 367–71.

Hirsch MJ. The refraction of children.In: Hirsch MJ, Wick R, eds. Vision of Children. Philadelphia: Chilton, 1963: 145–72.

Ingram RM, Barr A. Changes in refraction between the ages of 1 and 3 1/2 years. Br J Ophthalmol 1979; 63: 339–42.

Banks MS. Infant refraction and accommodation.In: Sokol S ed. Electrophysiology and Psychophysics: Their Use in Ophthalmic Diagnosis. Intl Ophthalmol Clin 1980; 20; 205–32.

Mohindra I, Held R. Refraction in humans from birth to five years.In: Fledelius HC, Alsbirk PH, Goldschmidt E, eds. Third International Conference on Myopia. Doc Ophthalmol Proc Series, The Hague: Junk, 1981; 28: 19–27.

Brookman KE. Ocular accommodation in human infants. Am J Optom Physiol Opt 1983; 60: 91–9.

Weale RA. A Biography of the Eye-Development, Growth, Age. London: Lewis, 1982: 94–120.

Fong DS. Postnatal ocular growth and its regulation. Intl Ophthalmol Clin 1992; 32: 25–33.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Goss, D.A., Wickham, M.G. Retinal-image mediated ocular growth as a mechanism for juvenile onset myopia and for emmetropization. Doc Ophthalmol 90, 341–375 (1995). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01268122

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01268122