Summary

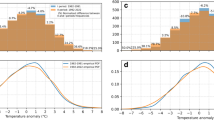

During the International Geophysical Year, 1958, and extending into 1959, the atmospheric electric field, current, and conductivity were recorded at Thule, Greenland (78°N). During the International Year of the Quiet Sun, 1964, records of the atmospheric electric field were obtained at the Amundsen-Scott Station at the South Pole (90°S). The diurnal variation averaged over the year of the normalized current at Thule and the normalized field at the South Pole show a surprisingly good agreement. These two curves combined into one represent the world time variation of the air-earth current (or field) in the Polar regions. Compared with the oceanic diurnal field variation obtained at the Carnegie ship cruises, the Polar curve shows a very similar shape but a much reduced amplitude. The maximum and minimum in the Polar regions are 1.07 and 0.92. The corresponding values on the oceans are 1.20 and 0.85. The difference is greater than the measuring error or statistical scatter and has to be accepted as real. No conclusive explanation of the deviation of the two curves can be offered.

The diurnal variation of the Polar data averaged over a season displays very smooth and similar curves during Northern autumn and winter. The spring and summer curves show a much more detailed structure with several maxima and minima. It is somewhat unexpected that the summer curve with a variety of fine structure is the flattest curve of all seasons. The minimum never drops below 0.95, and the maximum does not exceed 1.06. If the data are broken down into hourly means averaged over one month and split into an Arctic and Antarctic part, the similarity between corresponding curves of the same month vanishes for the months of January to July. This may partly be due to the fact that the number of fair-weather days of the individual month is too small to obtain a representative statistical average. Usually averaging over seven or more days is necessary for the oceanic pattern to emerge. However, there is a strong possibility that another agent besides the worldwide thunderstorm activity modulates the global circuit. The seasonal differences, and especially the difference between Arctic and Antarctic pattern, point to such a conclusion.

Zusammenfassung

Während des internationalen geophysikalischen Jahres (IGY) 1958 und bis in das Jahr 1959 hinein wurden Registrierungen des luftelektrischen Feldes, des Vertikalstromes und der Leitfähigkeit durchgeführt in Thule, Grönland (78°N). Während des internationalen Jahres der Ruhigen Sonne (IQSY) 1964 wurde das luftelektrische Feld an der Amundsen-Scott Station am Südpol (90°S) registriert. Die normalisierte Tagesvariation des Stromes, gemittelt über das Jahr 1958, in Thule, und die normalisierte Tagesvariation des Feldes am Südpol, gemittelt über das Jahr 1964, zeigen eine überraschend gute übereinstimmung. Diese zwei Tagesgänge sind zu einem gemittelten Tagesgang zusammengefasst, der den weltzeitlichen Tagesgang des Stromes oder des Feldes in den polaren Regionen repräsentiert. Im Vergleich zu dem Tagesgang des Feldes auf den Ozeanen, wie er während der Carnegie-Fahrten bestimmt wurde, zeigt der Tagesgang in polaren Gebieten einen sehr ähnlichen Verlauf, hat aber eine viel kleinere Amplitude. Die Werte für das Tagesmaximum und Minimum in polaren Gebieten sind 1.07 und 0.92. Die entsprechenden Werte auf dem Ozean sind 1.20 und 0.85. Der Unterschied ist so gross, dass er nicht durch Messungenauigkeit oder statistische Streuung hätte hervorgerufen werden können. Er muss deshalb als real akzeptiert werden. Eine Erklärung für diesen Unterschied konnte nicht gefunden werden.

Der Tagesgang in polaren Gebieten gemittelt über die verschiedenen Jahreszeiten zeigt für die nördlichen Herbst und Wintermonate sehr glatte und ähnliche Kurven. Die Frühlings- und Sommer-kurven haben eine mehr detaillierte Struktur mit mehreren Maxima und Minima. Es ist etwas überraschend, dass die Sommerkurve mit einer grossen Variation in der Feinstruktur die flacheste Kurve von allen Jahreszeiten ist. Die Minima sind niemals kleiner als 0.95 und die Maxima überschreiten nicht den Wert 1.06. Wenn die Daten weiter unterteilt werden in Tagesgänge gemittelt über Monate, dann verschwindet die Ähnlickeit zwischen arktischen und antarktischen Gängen desselben Monates für die Monate Januar bis Juli. Das mag teilweise darauf zurückzuführen sein, dass die Anzahl der Schönwettertage für die einzelnen Monate zu klein ist, um statistisch repräsentativ zu sein. Eine Mittelung über mindestens 7 Tage ist notwendig, damit der weltweite Tagesgang zum Vorschein kommt. Es ist aber auch sehr gut möglich, dass andere Einflüsse als die weltweite Gewittertätigkeit den Tagesgang modulieren. Unterschiede im Tagesgang der Jahreszeiten und auch des vollen Jahres legen eine solche Erklärung nahe.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

W. E. Cobb,The atmospheric electric climate at Mauna Loa, Hawaii. Presented at AMS-AGU Meeting, Washington, D.C. (1967). (In print).

R. E. Holzer,Studies of the universal aspect of atmospheric electricity. Contract No. AF 19(122)-254 (Final Report 1955).

H. Israël,Atmosphärische Elektrizität, Teil I:Grundlagen, Ionen, Leitfähigkeit (1957);Atmosphärische Elektrizität, Teil II:Felder, Ladungen, Ströme (1961). Akademische Verlagsgesellschaft Geest U. Portig KG. Leipzig.

H. Israël,Atmospheric Electicity, Volume I:Fundamentals, Ions, Conductivity. Israel Program for Scientific Translations, Jerusalem (1970).

H. W. Kasemir,Zur Strömungstheorie des luftelektrischen Feldes I. Arch. Meteor., Geophys., Biokl (A)3 (1950), 84–97.

H. W. Kasemir,Der Austauschgenerator. Arch. Meteor., Geophys., Biokl. (A)9 (1956), 357–370.

J. J. Krieg,Measurement of electric field, air-earth current, and conductivity. USASRDL Tech. Report 2085 (1959).

S. J. Mauchly,Studies in atmospheric electricity based on observations made on the Carnegie, 1915–1921. Res. Rep. Terr. Magn. Carnegie Institution V, 383–424 (1926).

R. Reiter,Felder, Ströme und Aerosole in der unteren Troposphäre. (Steinkopff Verlag, Darmstadt, 1964).

H. Schering,Registrierungen des spezifischen Leitvermögens der atmosphärischen Luft. Göttinger Nachrichten, 201–218 (1908).

F. J. H. Whipple andF. J. Scrase,Point discharge in the electric field of the earth. Geophysical MemoirsVII, No. 68, (1936), 3–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kasemir, H.W. Atmospheric electric measurements in the Arctic and Antarctic. PAGEOPH 100, 70–80 (1972). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00880228

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00880228