Summary

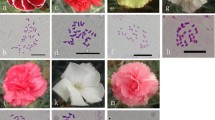

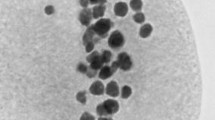

Ruellia tweediana and R. tuberosa are large flowered chasmogamous diploids (n=17) with normal meiosis and fertility. F 1 hybrids, successful in only one direction (R. tweediana x R. tuberosa), are vegetatively vigorous and possess 17 often heteromorphic bivalents with high degree of segregational irregularities. It is exclusively cleistogamous and completely pollen and seed sterile. Like F 1, the artificial amphidiploid (n=34) is also cleistogamous but shows preferential chromosome pairing with complete restoration of fertility. The parental chromosomes are sufficiently differentiated and cleistogamy is either genie or due to gene-cytoplasm interaction but sterility is entirely chromosomal. All floral parts excepting calyx are highly deformed. Such a deformity is associated with sterility in the F 1 but with fertility in the amphidiploid. This is perhaps the first case of origin by hybridization of a true breeding and fully fertile cleistogamous taxon from two chasmogamous species. It also shows the extent and nature of change in breeding system brought about by hybridization and/or polyploidy.

The chromosome numbers in the six, out of 16, obligate cleistogamous taxa (Table 4) show that they are high polyploids. Perhaps their origin has been in the same manner as in the present case.

Zusammenfassung

Ruellia tweediana und R. tuberosa sind großblütige, chasmogame Diploide (n=17) mit normaler Meiosis und Fertilität. Die F 1-Hybriden, die nur in einer Richtung gelingen (R. tweediana x R. tuberosa), sind vegetativ kräftig und besitzen häufig 17 heteromorphe Bivalente mit einem hohen Anteil an Spaltungsunregelmäßigkeiten. Die Hybride ist ausschließlich kleistogam und vollkommen pollen- und samensteril. Wie die F 1 ist auch die künstlich hergestellte Amphidiploide (n=34) kleistogam und zeigt eine präferentielle Chromosomenpaarung mit völliger Wiederherstellung der Fertilität. Die elterlichen Chromosomen sind genügend differenziert. Die Kleistogamie ist entweder genisch bedingt oder auf eine Gen-Cytoplasma-Interaktion zurückzuführen, die Sterilität ist ausschließlich durch die Chromosomen verursacht. Alle Teile der Blüte mit Ausnahme der Calyx sind stark deformiert. Bei der F 1 ist diese Deformation mit Sterilität verbunden, die amphidiploide Form ist jedoch fertil. Das ist vielleicht der erste Fall eines aus der Kreuzung zweier chasmogamer Spezies hervorgegangenen reinerbigen und voll fertilen kleistogamen Taxons. Es läßt sich auch der Umfang und die Art der durch Hybridisierung und durch Polyploidie verursachten Änderung des Zuchtsystems erkennen. Die Chromosomenzahl bei 6 von 16 obligaten kleistogamen Taxa (Tab. 4) zeigt, daß sie hochpolyploid sind. Vielleicht sind sie auf eine gleiche Weise wie im vorliegenden Falle entstanden.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Ascherson, P.: Über die Bestäubung bei Juncus bufonius. Bot. Zeitung 29, 551–554 (1871).

Baker, H. G.: Reproductive methods as factors in speciation in flowering plants. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 24, 177–191 (1959).

Burck, W.: Die Mutation als Ursache der Kleistogamie. Rec. Trav. Bot. Neerl. 2, 37–164 (1906).

Cave, M. S., et al.: Index to Plant chromosome Numbers. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1955–64.

Chase, A.: Notes on cleistogamy of grasses. Bot. Gaz. 45, 135–136 (1908).

Darlington, C. D. and A. P. Wylie: Chromosome Atlas of Flowering plants. London 1955.

Grant, V.: The influence of breeding habit on the outcome of natural hybridization in plants. Am. Naturalist 90, 319–322 (1956).

Gustafsson, Å.: Apomixis in higher plants II. The causal aspect of apomixis. Lunds Univ. Arsskr., 44 (2), 183–370 (1947).

Long, R. W.: Biosystematic investigations in South Florida populations of Ruellia (Acanthaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 51, 842–852 (1964).

Long, R. W.: Artificial interspecific hybridization in Ruellia (Acanthaceae). Amer. J. Bot. 53, 917–927 (1966).

Long, R. W., and L. J. Uttal: Some observations on flowering in Ruellia (Acanthaceae). Rhodora 64, 200–206 (1962).

McLean, R., and W. R. Ivimey-Cook: Text book of theoretical botany 2: 1351–1358. London: Longmans, Green and Co. 1956.

Mather, K., and A. Vines: Species crosses in Antirrhinum. II. Cleistogamy in the derivatives of A. majus x A. glutinosum, Heredity 5, 196–214 (1951).

Ornduff, R.: Index to plant chromosome numbers for 1965. Regnum Vegetabile Utrecht Vol. 50 and 55 (1967 and 1968).

Stebbins, G. L. Variation and evolution in plants. New York 1950.

Stebbins, G. L.: Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants. Amer. Naturalist 91, 331–354 (1957).

Uphof, J. C.: Cleistogamic flowers. Bot. Rev. 4, 21–49 (1938).

Uttal, L. J.: Observations on Ruellia purshiana in Virginia. Castanea 30, 228–230 (1965).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Khoshoo, T.N., Mehra, R.C. & Bose, K. Hybridity, polyploidy and change in breeding system in a Ruellia hybrid. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 39, 133–140 (1969). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00366490

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00366490