Summary

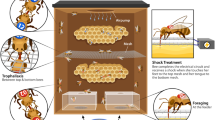

A honey bee colony operates as a tightly integrated unit of behavioral action. One manifestation of this in the context of foraging is a colony's ability to adjust its selectivity among nectar sources in relation to its nutritional status. When a colony's food situation is good, it exploits only highly profitable patches of flowers, but when its situation is poor, a colony's foragers will exploit both highly profitable and less profitable flower patches. The nectar foragers in a colony acquire information about their colony's nutritional status by noting the difficulty of finding food storer bees to receive their nectar, rather than by evaluating directly the variables determining their colony's food situation: rate of nectar intake and amount of empty storage comb. (The food storer bees in a colony are the bees that collect nectar from returning foragers and store it in the honey combs. They are the age group (generally 12–18 day old bees) that is older than the nurse bees but younger than the foragers. Food storers make up approximately 20% of a colony members.) The mathematical theory for the behavior of queues indicates that the waiting time experienced by nectar foragers before unloading to food storers (queue length) is a reliable and sensitive indicator of a colony's nutritional status. Queue length is automatically determined by the ratio of two rates which are directly related to a colony's nutritional condition: the rate of arrival of loaded nectar foragers at the hive (arrival rate) and the rate of arrival of empty food storers at the nectar delivery area (service rate). These two rates are a function of the colony's nectar intake rate and its empty comb area, respectively. Although waiting time conveys crucial information about the colony's nutritional status, it has not been molded by natural selection to serve this purpose. Unlike “signals”, which are evolved specifically to convey information, this “cue” conveys information as an automatic by-product. Such cues may prove more important than signals in colony integration.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Allen MD (1963) Drone production in honey-bee colonies (Apis mellifera L.). Nature 199:789–790

Allen MD (1965) The effect of a plentiful supply of drone comb on colonies of honeybees. J Apic Res 4:109–119

Boch R (1956) Die Tänze der Bienen bei nahen und fernen Trachtquellen. Z Vergl Physiol 38:136–167

Brian MV (1983) Social insects. Ecology and behavioural biology. Chapman and Hall, London New York

Dadant CC (1975) Beekeeping equipment. In: The hive and the honey bee. Dadant and Sons, Hamilton, pp 303–328

Free JB (1967) The production of drone comb by honeybee colonies. J Apic Res 6:29–36

Free JB, Williams IH (1975) Factors determining the rearing and rejection of drones by the honeybee colony. Anim Behav 23:650–675

Frisch K von (1967) The dance language and orientation of bees. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Gould JL, Henerey M, MacLeod MC (1970) Communication of direction by the honey bee. Science 169:544–554

Gould JL, Gould CG (1988) The honey bee. Freeman, New York

Hangartner W (1969) Structure and variability of the individual odor trail in Solenopsis geminata Fabr. (Hymenoptera, Formicidae). Z Vergl Physiol 62:111–120

Heinrich B (1981) The mechanisms and energetics of honeybee swarm temperature regulation. J Exp Biol 91:25–55

Hölldobler B (1971) Recruitment behavior in Camponotus socius (Hym. Formicidae). Z Vergl Physiol 75:123–142

Hölldobler B (1977) Communication in social Hymenoptera. In: Sebeok TA (ed) How animals communicate. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, pp 418–471

Jeanne RL (1986) The organization of work in Polybia occidentalis: costs and benefits of specialization in a social wasp. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 19:333–341

Kronenberg F, Heller HC (1982) Colonial thermoregulation in honey bees (Apis mellifera). J Comp Physiol 148:65–76

Law AM, Kelton WD (1982) Simulation modeling and analysis. McGraw-Hill, New York

Lewis BD, Gower DM (1980) Biology of communication. Wiley & Sons, New York

Lindauer M (1948) Über die Einwirkung von Duft- und Geschmacksstoffen sowie anderer Faktoren auf die Tänze der Bienen. Z Vergl Physiol 31:348–412

Lindauer M (1952) Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Arbeitsteilung im Bienenstaat. Z Vergl Physiol 34:299–345

Lindauer M (1954) Temperaturregulierung und Wasserhaushalt im Bienenstaat. Z Vergl Physiol 36:391–432

Lindauer M (1961) Communication among social bees. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Lloyd JE (1983) Bioluminescence and communication in insects. Ann Rev Entomol 28:131–160

Markl H (1985) Manipulation, modulation, information, cognition: some of the riddles of communication. In: Hölldobler B, Lindauer M (eds) Experimental behavioral ecology and sociobiology. Sinauer, Sunderland, pp 163–194

Martin H, Lindauer M (1966) Sinnesphysiologische Leistungen beim Wabenbau der Honigbiene. Z Vergl Physiol 53:372–404

Michener CD (1974) The social behavior of the bees. A comparative study. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Milum VG (1955) Honey bee communication. Am Bee J 95:97–104

Morse PM (1958) Queues, inventories, and maintenance. Wiley-& Sons, New York

Omholt SW (1987) Thermoregulation in the winter cluster of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. J Theor Biol 128:219–231

Otte D (1974) Effects and functions in the evolution of signaling systems. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 5:385–417

Rinderer TE (1981) Volatiles from empty comb increase hoarding by the honey bee. Anim Behav 29:1275–1276

Rinderer TE (1982) Regulated nectar harvesting by the honeybee. J Apic Res 21:74–87

Rinderer TE (1983) Regulation of honey bee hoarding efficiency. Apidol 14:87–92

Schneider SS, Stamps JA, Gary NE (1986a) The vibration dance of the honey bee. I. Communication regulating foraging on two time scales. Anim Behav 34:377–385

Schneider SS, Stamps JA, Gary NE (1986b) The vibration dance of the honey bee. II. The effects of foraging success on daily patterns of vibration activity. Anim Behav 34:386–391

Schoener TW (1971) Theory of feeding strategies. Ann Rev Ecol Syst 2:369–404

Seeley TD (1982) Adaptive significance of the age polyethism schedule in honeybee colonies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 11:287–293

Seeley TD (1985) Honeybee ecology. A study of adaptation in social life. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Seeley TD (1986) Social foraging by honeybees: how colonies allocate foragers among patches of flowers. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 19:343–354

Seeley TD (1987) The effectiveness of information collection about food sources by honey bee colonies. Anim Behav 35:1572–1575

Seeley TD, Levien RA (1987) Social foraging by honeybees: how a colony tracks rich sources of nectar. In: Menzel R, Mercer A (eds) Neurobiology and behavior of honeybees. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg New York, pp 38–53

Singh J (1972) Great ideas of operations research. Dover, New York

Sokal RR, Rohlf FJ (1981) Biometry. Freeman, New York

Sorensen AA, Busch TM, Vinson SB (1985) Control of food influx by temporal subcastes in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 17:191–198

Traniello JFA (1977) Recruitment behavior, orientation, and the organization of foraging in the carpenter ant Camponotus pennsylvanicus DeGeer (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 2:61–79

Tschinkel WR (1988) Social control of egg-laying rate in queens of the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Physiol Entomol 13:327–350

Visscher PK, Seeley TD (1982) Foraging strategy of honeybee colonies in a temperate deciduous forest. Ecology 63:1790–1801

Williams GC (1966) Adaptation and natural selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Williams GC (1985) A defense of reductionism in evolutionary biology. Oxford Surv Evol Biol 2:1–27

Wilson EO (1962) Chemical communication among workers of the fire ant Solenopsis saevissima (Fr. Smith). 1. The organization of mass-foraging. Anim Behav 10:134–147

Wilson EO (1971) The insect societies. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Wilson EO (1985) The sociogenesis of insect colonies. Science 228:1489–1495

Wilson EO, Hölldobler B (1988) Dense heterarchies and mass communication as the basis of organization in ant colonies. Tr Ecol Evol 3:65–68

Winston ML (1987) The biology of the honey bee. Harvard University Press, Cambridge

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seeley, T.D. Social foraging in honey bees: how nectar foragers assess their colony's nutritional status. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 24, 181–199 (1989). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292101

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00292101