Abstract

Informational lobbying — the use by interest groups of their (alleged) expertise or private information on matters of importance for policymakers in an attempt to persuade them to implement particular policies — is often regarded as an important means of influence. This paper analyzes this phenomenon in a game setting. On the one hand, the interest group is assumed to have private information which is relevant to the policymaker, whilst, on the other hand, the policymaker is assumed to be fully aware of the strategic incentives of the interest group to (mis)report or conceal its private information.

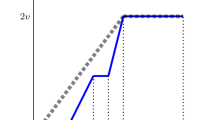

It is shown that in a setting of partially conflicting interests a rationale for informational lobbying can only exist if messages bear a cost to the interest group and if the group's preferences carry information in the ‘right direction’. Furthermore, it is shown that it is not the content of the message as such, but rather the characteristics of the interest group that induces potential changes in the policymaker's behavior. In addition, the model reveals some interesting results on the relation between, on the one hand, the occurrence and impact of lobbying and, on the other hand, the cost of lobbying, the stake which an interest group has in persuading the policymaker, the similarity between the policymaker's and the group's preferences, and the initial beliefs of the policymaker. Moreover, we relate the results to some empirical findings on lobbying.

qu]Much of the pressure placed upon government and its agencies takes the form of freely provided “objective” studies showing the important outcomes to be expected from the enactment of particular policies (Bartlett, 1973: 133, his quotation marks).

qu]The analysis here is vague. What is needed is an equilibrium model in which lobbying activities have influence. Incomplete information ought to be the key to building such a model that would explain why lobbying occurs (information, collusion with decision makers, and so on) and whether lobbying expenses are socially wasteful. (Tirole, 1989: Ch. 1.3, p. 77, Rentseeking behavior).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Appels, A. (1985). Political economy and enterprise subsidies. Tilburg: Tilburg University Press.

Aranson, P. and Hinich, M. (1979). Some aspects of the political economy of campaign laws. Public Choice 34: 435–461.

Aumann, R. and Kurz, M. (1977). Power and taxes. Econometrica 45: 1137–1161.

Austin-Smith, D. (1987). Interest groups, campaign contributions, and probabilistic voting. Public Choice 54: 123–139.

Bartlett, R. (1973). Economic foundations of politic power. New York: The Free Press.

Bauer, R., De Sola Pool, I. and Dexter, A. (1963, 2nd ed. 1972). American business & public policy: The politics of foreign trade. Chicago: Aldine Atherton Inc.

Becker, G. (1983). A theory of competition among pressure groups for political influence. Quarterly Journal of Economics 98: 371–400.

Berry, J. (1977). Lobbying for the people. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Berry, J. (1984). The interest group society. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

Calvert, R. (1985). The value of biased information: A rational choice model of political advice. Journal of Politics 47: 530–535.

Cho, I. and Sobel, J. (1990). Strategic stability and uniqueness in signaling games. Journal of Economic Theory 50: 381–413.

Crawford, V. and Sobel, J. (1982). Strategic information transmission. Econometrica 50: 1431–1451.

Farrell, J. (1988). Communication, coordination and Nash equilibrium. Economics Letters 27: 209–214.

Farrell, J. and Gibbons, R. (1985). Cheap talk with two audiences. American Economic Review 79: 1214–1223.

Gross, B. (1972). Political process, (header: persuasion). In The International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences. Vol. 12. London: Collier-Macmillan.

Grossman, S. and Hart, O. (1983). An analysis of the principal-agent problem. Econometrica 51: 7–45.

Kambhu, J. (1988). Unilateral disclosure of information by a regulated firm. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 10: 57–82.

Kirchner, E. and Schwaiger, K. (1981). The role of interest groups in the European Community. Hampshire: Glower.

Milgrom, P. (1981). Good news and bad news: Representation theorems and applications. Bell Journal of Economics 12: 380–391.

Mitchell, W.C. (1990). Interest groups: Economic perspectives and contributions. Journal of Theoretical Politics 2: 85–108.

Mueller, D. and Murrell, P. (1986). Interest groups and the size of government. Public Choice 48: 125–145.

Ornstein, N. and Elder, S. (1978). Interest groups, lobbying and policymaking. Washington: Congressional Quarterly Press.

Potters, J. (1990). Fixed cost messages. Mimeo. University of Amsterdam.

Potters, J. and Van Winden, F. (1990). Modelling political pressure as transmission of information. European Journal of Political Economy 6: 61–88.

Schlozman, K. and Tierney, J. (1986). Organized interests and American democracy. New York: Harper & Row.

Schneider, F. and Naumann, J. (1982). Interest groups in democracies — How influential are they?: An empirical examination for Switzerland. Public Choice 42: 281–303.

Sobel, J. (1985). A theory of credibility. Review of Economic Studies 52: 557–573.

Stekelenburg, J. (1988). Ook ‘non-profit’ zoekt profijt. (Also ‘non-profit’ seeks profit). In (no Ed.), Het gebeurt in Den Haag. Een open boekje over lobby (It happens in the Hague. An open book about lobbying). The Hague: SDU.

Tedeshi, J., Schlenker, B. and Bonoma, T. (1973). Conflict, power and games. Chicago: Aldine.

Tirole, J. (1989). The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Tullock, G. (1980). Efficient rent-seeking. In J. Buchanan, R. Tollison, and G. Tullock (Eds.), Towards a theory of the rent-seeking society. College Station: Texas A&M University Press.

Van der Putten, J. (1980). Haagse Machten(The Hague's Powers). The Hague: Staatsuitgevery.

Zeigler, H. and Baer, M. (1969). Lobbying: Interaction and influence in American State Legislatures. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We are grateful for comments made by participants of the workshop ‘Economic Models of Political Behavior’ of the European Consortium of Political Research (Bochum, 2–7 April 1990), the European Public Choice Society Meeting (Meersburg, 18–21 April 1990), the World Congress of the Econometric Society (Barcelona, 22–28 August, 1990), and the Congress of the European Economic Association (Lisbon, 31 August – 2 September 1990). In particular we acknowledge the helpful and stimulating comments by Eric Drissen, John Hudson, Karl Dieter Opp, Arthur Schram, and Franz Wirl.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Potters, J., van Winden, F. Lobbying and asymmetric information. Public Choice 74, 269–292 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00149180

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00149180