Abstract

The main focus of this paper is to establish the community diversity pattern of vegetation in exposed-cliffs in the Mediterranean region and the relative importance of some environmental factors. Consequently, a study of a calcareous mesa in C-N Spain has been carried on, based on constrained ordination — CCA. The spatial scale approach for sampling was the patch on the cliff. The total number of taxa was 117 and the average per patch was 15. It is remarkable that the highest frequency plants are not rock specialists (chasmophytes), but generalist nanophanerophytes and chamaephytes.

A community pattern has been detected and related to the geomorphology and lithology of the cliff-nine communities. However, those patches of the vertical areas are very heterogeneous in number of taxa and size. Nevertheless, the community pools seem constant for each vertical cliff zone. Based on the ordination results and linear models, this variability may be interpreted as different succession stages of a cyclic process. The primary colonization of the bare rock by chasmophytes leads to the accumulation of soil because of the biological activity and the stock-trampling ability of these specialist plants. After that, the patches may be invaded by generalist chamaephytes (Festuco-Poetalia) and later even by several nanophanerophytes (Sideritido-Salvion lavandulifoliae and Berberidion vulgaris). The root activity of these plants in combination with other erosive events can return the system to the beginning.

A second objective included in the paper was related to the capacity of phytosociological approach, widely used in the Mediterranean region, to describe this type of community pattern. The surveyed mountain had previously studied in phytosociological terms. These relevés were compared through an assignation procedure — see text — to our community pattern. Both approaches seem to agree with high correspondence, but there are some differences that must be pointed out. They are related to the fact that spatial/ ecological heterogeneity does not always agree with the idealized phytosociological vegetation models, where only chasmophytic elements are considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- DCA =:

-

detrended correspondence analysis

- CCA =:

-

canonical correspondence analysis

References

AlvesR. J. V. & KolbekJ. 1993. Penumbral rock communities in campo rupestre sites in Brazil. Journal of Vegetation Science 4: 357–366.

BartlettR. M., Matthes.SearsU. & LarsonD. W. 1990. Organization of the Niagara Escarpment cliff community. II. Characterization of the physical environment. Canadian Journal of Botany 68: 1931–1941.

BemmerleinF. A. 1986. Bearbeitung von Lebensformengruppen mit numerischen Methoden. Untersuchungen an der Vegetation von Mauern in NW Spanien. Tuexenia 6: 391–403.

Braun-BlanquetJ. 1964. Pflanzensoziologie. Grundzüge der Vegetationskunde. 3. Aufl. Springer, Wien

BurbanckM. P. & PlattR. B. 1964. Granite outcrop communities of the Piedmont Plateau in Georgia. Ecology 45: 292–306.

BurrowsC. J. 1990. Processes of vegetation change. Unwin Hyman, Boston, Massachusets. USA.

CastroviejoS. et al. (1986–1994). Flora Iberica. Vols. 1–4. C.S.I.C. Madrid.

ChapinIIIF. S., WalkerL. R., FastieC. L. & SharmanL. C. 1994. Mechanism of primary succession following deglaciation at Glacier Bay, Alaska. Ecological Monograghs 64: 149–175.

DaviesP. H. 1951. Cliff vegetation in the eastern Mediterranean. Journal of Ecology 39: 63–72.

delMoralR. & WoodD. M. 1993. Early primary succession on the volcano Mount St. Helens. Journal of Vegetation Science 4: 223–234.

Díaz-González, T. E. 1989. Biogeografía y sintaxonomía de las comunidades rupícolas (ensayo preliminar para una revisión de la clase Asplenietea trichomanis en la península ibérica, Baleares y Canarias). Com. IX Jornadas de Fitosociología. U. Alcalá de Hanares.

DaddM. E., SilvertownJ., McConwayK., PottsJ. & CrawleyM. 1994. Application of the British National Vegetation Classification to the communities of the Park Grass Experiment through time. Folia Geobotanica et Phytotaxonomica. 29: 321–334.

Escudero, A. 1992. Estudio fitoecológico de las comunidades rupícolas y glerícolas del macizo del Moncayo. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid.

EscuderoA., GavilánR. & PajarónS. 1994. Saxicolous communities in the Sierra del Moncayo (Spain). A classificatory approach. Coenoses 9(1): 15–24.

EscuderoA. & HerreroA. 1995. Algunas comunidades saxícolas del Moncayo. Lazaroa 15: 193–204.

EscuderoA. & PajarónS. 1994. Numerical syntaxonomy of the Asplenietalia petrarchae in the Iberian Peninsula. Journal of Vegetation Science 5(1): 205–214.

EscuderoA. & PajarónS. 1995. La vegetación rupícola del Moncayo silíceo. Una aproximación basada en ordenaciones. Lazaroa 16: 103–130.

EscuderoA. & RegatoP. 1992. Ordenación de la vegetación de las torcas de la Serranía de Cuenca y sus relaciones con algunos factores del medio. Orsis 7: 41–55.

FarrelT.M. 1991. Models and mechanisms of succession: an example from a rocky intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 61: 95–113.

Gómez-CampoC. 1987. Libro Rojo de las especies vegetales amenazadas de España Peninsular e Islas Baleares. ICONA, Madrid.

GoodallD. W. 1966. Deviant index — a new tool for numerical taxonomy. Nature 210: 216.

GuitiánJ. & SánchezJ. M. 1992. Flowering phenology and fruit set of Petrocoptis grandiflora (Caryophyllaceae). International Journal of Plant Science 153: 409–412.

HakesW. 1994. On the predictive power of numerical and Braun-Blanquet classification: an example from beechwoods. Journal of Vegetation Science 5: 133–160.

HerreraM. 1988. Biología y ecología de Viola cazorlensis I. Variabilidad de caracteres florales. Anales Jardín Botánico de Madrid 45(1): 233–246.

HeywoodV. H. 1953. El concepto de asociación en las comunidades rupícolas. Anales Instituto Botánico Cavanilles 11(2): 463–481.

HillM. O. 1989. Computerized matching of relevés and association tables, with an application to the British National Vegetacion Classification. Vegetatio 83: 187–194.

HillM. O. & GauchH. G. 1980. Detrended Correspondence Analysis: an improved ordination technique. Vegetatio 42: 47–58.

HillM. O., BunceR. G. H. & ShawM. W. 1975. Indicator species analysis, a divisive polythetic method of classification and its application to a survey of native pinewoods in Scotland. Journal of Ecology 63: 597–613.

HruškaK. 1987. Syntaxonomic study of the Italian wall vegetation. Vegetatio 73: 13–20.

IriondoJ. M., González-BenitoE. & MartínC. 1994. Estudios demográficos y fenológicos en el endemismo madrileñoErodium paularense Fdez.-Glez. & Izco (Geraniaceae). Studia Oecologica 10/11: 185–191.

JacksonG. & SheldonJ. 1949. The vegetation of magnesian limestone cliffs at Markland Grips near Sheffield. Journal of Ecology 37: 38–50.

JohnE. A. & DaleM. R. T. 1990. Environmental correlates of species distributions in a saxicolous lichen community. Journal of Vegetation Science 1: 385–392.

KazmierczakE., van derMaarelE. & NoestV. 1995. Plant communities in kettle-holes in central Poland: chance ocurrence of species? Journal of Vegetation Science 6: 863–874.

LarsonD. W., SpringS. H., Matthes-SearsU. & BartlettR. M. 1989. Organization of Niagara Escarpment cliff community. Canadian Journal of Botany 67: 2731–2742.

Matthes-SearsU. & LarsonD. W. 1995. Rootong characteristics of trees in rock: a study of Thuja occidentalis on cliff faces. International Journal of Plant Science 156: 679–686.

MeierH. & Braun-BlanquetJ. 1934. Prodrome des groupements végétaux. 2. (Classe des Asplenietales rupestres-Groupements rupicoles). Marie-Lavit. Montpellier.

MontserratP. 1975. Comunidades relícticas geomorfológicas. Anales Instituto Botánico Cavanilles 32(2): 397–404.

MontserratP. 1980. Continentalidades climáticas pirenaicas. Publicaciones del Centro Pirenaico de Biología Experimental 12: 63–83.

MotaJ., GómezF. & ValleF. 1991. Rupicolous vegetation of the Betic ranges (south Spain). Vegetatio 94: 101–113.

MucinaL. & van derMaarelE. 1989. Twenty years of numerical syntaxonomy. Vegetatio 12: 116.

NavarroG. 1990. Contribución al conocimiento de la flora del Moncayo. Opuscula Botanica Pharmaciae Complutensis 5: 5–64.

NavarroL., GuitiánJ. & GuitiánP. 1993. Reproductive biology of Petrocoptis grandiflora Rothm, (Caryiophyllaceae), a species endemic to Northwest Iberian Peninsula. Flora 188: 253–261.

ØklandR.H. 1990. Vegetation ecology: theory, methods and applications with reference to Fennoscandia. Sommerfeltia, Suppl. 1: 9–233.

OksanenJ. & HuttunenP. 1989. Finding a common ordination for several data sets by individual differences scaling. Vegetatio 83: 137–145.

OksanenJ. & TonteriT. 1995. Rate of compositional turnover along gradients and total gradient lenght. Journal of Vegetation Science 6: 815–824.

OostingO. T. & AndersonL. E. 1937. The vegetation of a barefaced cliff in western North Carolina. Ecology 18: 280–292.

OrlóciL. 1978. Multivariate analysis in vegetation research. 2nd ed. Junk. The Hague.

Pellicer, F. 1984. Geomorfología de las cadenas Ibéricas entre el Jalón y el Moncayo. Cuad. Est. Borjanos 11/12. Zaragoza.

PickettS. T. A. & WhiteP. S. (eds) 1985. The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics. Academic Press, London.

Rivas-MartínezS. 1960. Roca, clima y comunidades rupícolas. Sinopsis de las alianzas hispanas de Asplenietea rupestris. Anales Real Academia de Farmacia 26: 153–168.

ShureD. J. & RagsdaleH. L. 1977. Patterns of primary succession on granite outcrop surfaces. Ecology 58: 993–1006.

Snogerup, S. 1971. Evolutionary and plant geographical aspects of chasmophytic communities. In: Davis, P.H., Harper, P.C. & Hedge, I.C. (eds). Plant life of South-West Asia, pp. 157–170. Edinburgh.

StanckW. & OrlóciL. 1973. A comparison of Braun-Blanquet's method with sum-of-squares agglomeration for vegetation classification. Vegetatio 27: 323–345.

ter BraakC. 1987. The analysis of vegetation-environment relationships by canonical correspondence analysis. Vegetatio 69: 69–77.

ter BraakC. 1988. CANOCO — a Fortran program for canonical community ordination by (partial) (detrended) (canonical) correpondence analysis, principal component analysis and redundance analysis (version 2.19). Groep Landbouwwiskunde. Wageningen.

ter BraakC. & PrenticeI. 1988. A theory of gradient analysis. Advances in Ecological Research 18: 271–317.

TilmanD. 1982. Resource competition and community structure. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey, USA.

TonteriT., MikkolaK. & LahtiT. 1990. Compositional gradients in the forest vegetation of Finland. Journal of Vegetation Science. 1: 691–698.

TutinT.G. et al. (1964–1980). Flora Europea. Vols 1–5 Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

WesthoffW. & van derMaarelE. 1978. The Braun Blanquet approach. In: WhittakerR. H. (ed). Classification of Plant Communities. 2nd ed. Junk, The Hague.

WieglebG. 1986. Grenzen und Möglichkeiten der Daten-analyse in der Pflanzenökologie. Tüexenia 6: 365–377.

WildiO. 1989. A new numerical solution to traditional phytosociological tabular classification. Vegetatio 81: 95–106.

WinterringerG. S. & VestalG. 1956. Rock-ledge vegetation in southern Illinois. Ecological Monographs 26: 105–130.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

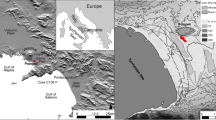

Escudero, A. Community patterns on exposed cliffs in a Mediterranean calcareous mountain. Vegetatio 125, 99–110 (1996). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00045208

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00045208