Abstract

In this study, we evaluated the premium rent of refurbished apartment houses in Greater Tokyo. We found that as a residential building’s age increased, the premium rent decreased. Male tenants in the age group of 20–30 years showed the highest willingness to pay (WTP). In addition, a high degree of residential satisfaction and the sense of expense toward rent had negative effects on the WTP toward premium rent.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

1.1 Background to the Research

The Basic Plan for Housing, formulated in March 2016, indicates a new direction for housing based on the recognition that there have been delays in conversion of the market, from being primarily a market for newly constructed housing to a market that applies to existing homes. One recorded indicator of specific outcomes is the expansion of the scale of the Refurbishment Market from 7 trillion yen (2013) to 12 trillion yen (2025). There are expectations that the market flow for existing homes will be promoted through refurbishment.

Nevertheless, looking at the refurbishment ratio in recent years, although the figures are limited to owner-occupied residences, the refurbishment ratio (annual average) for apartments has stayed at a low level of 4.5%. Looking at apartments within rented houses, one reason for the lack of progress in refurbishment work is the lack of expectations for increased rent or occupancy rates following such work (Komatsu and Chau 2015). Grasping the impact of refurbishment work on rent is vital to estimate the profitability of investment in such work and for appropriate decision-making.

1.2 Purpose of the Research

This research aims to consider the degree of impact that refurbishment work for rental apartments in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area has on rent, based on a quality assessment of such work and taking the degree of change as a rental premium.

Note that the rental premium in this research is defined to be the amount of increase in rent that is thought to be the maximum payment that a lessee would consider acceptable to pay following refurbishment work on the same dwelling.

1.3 Previous Research

Much of the previous research concerning refurbishment has been on the state of such refurbishment (Cho and Takada 2015; Takagi et al. 2002).

However, there is a limited amount of research discussing the impact that refurbishment work has on housing prices. One reason is the lack of information arranged in a way that relates price information on housing to the repair history information. Research that discusses the impact that refurbishment work has on housing prices includes, for example, Iwata and Yamaga (2008) and Harano et al. (2012), but these both look at refurbishment work on owner-occupied dwellings.

There has been insufficient research to date concerning the impact on rent from the perspective of a lessee who is the beneficiary of refurbishment work on rented houses.

2 Research Method

2.1 Analytical Method

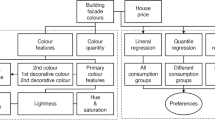

First is to construct a model for a quality assessment of refurbishment work by rental residents. Specifically, an evaluation using the state of functional sufficiency as a rental apartment and the satisfaction levels of such residents is adopted. This is aimed at rigorously accentuating in advance the contribution of the refurbishment work which increases the utility of residents and at giving an interpretation to the monetary evaluation referred to below. Next, to clarify the resident attributes and dwelling attributes that have an impact on such evaluation, multinomial probit models are estimated. Such models are estimated with 18 types of refurbishment work. Furthermore, to estimate the rental premium for the dwelling after such refurbishment work based on these factors, the tobit model with the target objective variable of the rate of the willingness to pay to the rent level is estimated as the Bayes model. Finally, a simulation of the rental premium after the refurbishment work using such model was conducted, grasping the differences in willingness to pay with the categories according to gender and age of lessee.

The data used in the above analysis was collected via a questionnaire survey of lessees of residences in rental condominiums and apartments in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area, which is compiled as stated preference data concerning refurbishment work (see Table 14.1).

2.2 Data Used

A questionnaire survey was conducted with lessees aged in their 20s to 50s at the time of survey dwelling in rental condominiums and apartments in the Tokyo Special Wards, Yokohama City, Saitama City, and Chiba City with 4500 valid responses received (see Table 14.1). As stated preference data, the information was respectively compiled for preference for refurbishment, amount willing to pay, residents’ attributes, and building/dwelling attributes.

The basic statistics are as follows (see Table 14.2).

3 Categories Based on the Quality Assessment of the Refurbishment Work by the Lessee

3.1 Setting Types of Relevant Refurbishment Work

In this study, the refurbishment work is separated into three categories: indoor work, equipment work, and external work looking at the following total 18 works by type (see Table 14.3).

4 Setting the Quality Assessment of Refurbishment Work

The level of satisfaction (utility) of resident needs to increase to generate a rental premium because it is taken as a conversion of change in utility unit to currency unit.

So a quality assessment of the refurbishment work was conducted focusing on the relationship between the details of the refurbishment work and the degree of satisfaction of residents. For example, Kano et al. (1984) propose categories using the state of physical sufficiency and the degree of user satisfaction as quality factors for the product.

In this research, reference is given to the categories of Kano et al. (1984), using the state of functional sufficiency of the building and the degree of residents’ (lessees’) satisfaction to assess the quality of the refurbishment work with the evaluationFootnote 1 of the refurbishment work by the lessee based on the following seven categories (see Table 14.4).

5 Attribute Analysis of Lessees Pertaining to the Quality Assessment of the Refurbishment Work

5.1 Investigating the Model

We will analyze the factors that affect the lessees’ evaluation of a total of 18 types of refurbishment work based on seven categories of evaluation categorized in the preceding paragraph. The multinomial probit model is used when conducting such analysis. This was because an investigation by the multinomial logit model was done beforehand, but the null hypothesis was dismissed as the result of the inspection concerning independence of irrelevant alternatives (IIA).

The objective variables (Rji) are the seven categories of evaluation for each of the 18 types of refurbishment work, namely, “evaluation as attractive,” “unified evaluation,” “evaluation as obvious,” “indifferent evaluation,” “evaluation as already sufficient,” “reverse evaluation,” and “evaluation of resignation.” The independent variables (Xi) include the residents’ attributes and the dwelling attributes. This is formularized as follows. Note the estimated number of parameters totals 1728. In addition, Bayesian estimates are used to estimate each parameter.

Multinomial probit model uses the “evaluation as attractive” as a base and makes 18 estimates for each type of refurbishment work.

Note that Rji = α + βjXi + ui

5.2 Model Estimation Results

5.2.1 Overall Evaluation Features of the Refurbishment Work Viewed by Gender and by Age

Based on the results of the Bayesian estimates from the multinomial probit model (see Table 14.5), we first grasp the points of difference in the evaluation of the refurbishment work focusing on the gender and age of residents (see Table 14.6).

Note that only age and the intersection between age and gender from the parameters estimated by the Bayesian estimate are listed in Table 14.5.

Focusing on the selection probability (odds ratio) for each type of evaluation in relation to the selection probability of the “evaluation as attractive,” 1 was taken to be the basis and split into below a multiple of 1.0 and above a multiple of 1.0, with the number of evaluations aggregated, respectively.

Looking at females, it is observed that the number of evaluations with a multiple of 1 and above (a tendency for this evaluation to be selected) for the selection probability ratio for each type of evaluation relative to the selection probability of “evaluation as attractive” was the majority for each age group (see Table 14.6). This indicates that the refurbishment work is not necessarily recognized as an evaluation as attractive that increases the level of satisfaction. Specifically, for the “evaluation as obvious” and the “evaluation of resignation,” the number of cases where the selection probability of such evaluation relative to the “evaluation as attractive” is a multiple of 1 and above exceeded 20% for all age groups. That is, since females have strong tendency to recognize the implementation of refurbishment work as something too obvious to be done, it is difficult for them to forecast that rent will increase following such work. On the other hand, of the evaluation of the refurbishment work by all residents including males, focusing on evaluations with a multiple of 1.0 and above for the selection probability relative to “evaluation as attractive” more than 10% in each age group provides an “evaluation as already sufficient,” which is a high ratio compared to females. That is, there is a relatively large number of residents compared to females who are satisfied with the current dwelling and do not see the need for refurbishment work at the present point in time.

5.2.2 Evaluation Features of Each Type of Refurbishment Work Viewed by Gender and by Age

A large proportion of females in each age group select the “evaluation as obvious” for the evaluation of aesthetics-related work, i.e., “replacement of wooden fittings,” and equipment-related work, i.e., “switching to a Western toilet (with washlet),” “switching to a large bathtub (reheating),” and “installation of an interphone with television monitor” (see Table 14.5). Therefore, it is thought that it would be difficult to forecast an increase in rent due to such work, and these are thought to be work that should be considered in at least maintaining the current rent level. In addition, a large proportion of females in their 40s and 50s select the “indifferent evaluation” for the evaluation of external work that “improve the design due to exterior painting” or “improve the design due to roof painting,” so it is difficult to anticipate an increase in rent due to such work.

On the other hand, a higher proportion of females in each group selected “evaluation as attractive” over “evaluation as obvious” for their evaluation in relation to “work that change the floor plan of the residence” and “work that change Japanese-style rooms.”

Therefore, it can be expected that such work could contribute somewhat to lifting rent.

As in the above, the implementation of refurbishment work does not necessarily increase the level of satisfaction of residents, and it is important to be aware that not doing such work could lead to dissatisfaction and calls for the current rent to be lowered.

6 Awareness Analysis Concerning the Rental Premium Following Refurbishment Work

6.1 Investigating of the Model

Since willingness to pay, WTP, is observed with 0 yen as threshold value, we will use the tobit model. The target objective variable is considered to be the rental premiumFootnote 2, which is the proportion relative to the willingness to pay: WTP rent level taking account of the ease of comparison. In addition, such model is estimated to be the Bayes modelFootnote 3. The merit is that it can generate as a latent variable those variables that otherwise are taken together to be 0 yen without being observed since they take negative values.

Note that, for the 18 types of refurbishment work, 5 levels of dummy variables are aggregated by category (see Table 14.3).

The payment function for the rental premium on the dwelling following refurbishment work is formularized as follows. The independent variables are the resident’s attributes, property attributes, and the dummy variable for the refurbishment work based on the results of the polynomial logistic regression analysis mentioned in 4 above, and we also included the number of locations requiring refurbishment. In addition, the cognitive evaluation of the current dwelling is thought to have an impact on the willingness-to-pay amount, so the level of satisfaction with the dwelling and sense of expensiveness toward the rent are respectively used as variables related to the cognitive evaluation of the residents dwelling. The general expression is as follows.

We assume that τ = 1/σ2 and that prior distributions of β and τ have normal distribution and gamma distribution, respectively, as follows, with reference to Terui (2010) and Furutani (2008).

The conditional posterior distribution is as follows when Yi is given.

Note here that definitions are made as follows.

Y* shows a truncated normal distribution as set out below, and we apply Gibbs sampling to it.

6.2 Model Estimation Results

The MCMC (Markov chain Monte Carlo) method is a method for simulating the Markov chain with ergodic theory (Table 14.7).

Therefore, it is necessary to confirm a steady state that is not dependent on the initial value. In this research, a convergence test based on Gelman-Rubin statistics was done, and such statistics were 1.00 for all variables confirming them to be 1.05 or below. Therefore, it can be judged to be converging.

Looking at the 95% confidence interval of parameters, each parameter also has a stable sign condition at such level. In this regard, a significant result different from zero can be said to be obtained.

6.3 Measurement of the Rental Premium Through Simulation Using the Model

The rental premium by gender and age of residents is estimatedFootnote 4 using the model estimated above. In addition, in terms of the time for undertaking the refurbishment work, this was done by combining with a comparison of the rental premiums at points 20 years and 40 years since construction.

Note that three types of relevant refurbishment work were set with the intent of grasping the change in the rental premium due to an increase in the number of places where work is done.

-

1.

Comparison of the rental premium following indoor aesthetic work, equipment work and external work

There is no recognition of a rental premium for any group of residents by gender or age group in relation to dwellings that were refurbished at the point 20 years or 40 years since construction (see Table 14.8).

Table 14.8 Estimation results for rental premium following refurbishment work views by residents’ gender and age Considering the results of the multinomial logit model in Table 14.6 (see Tables 14.5 and 14.6), such result is estimated to be due to the tendency of females in their 30s and older in particular to consider “evaluation as obvious” while refurbishment work evaluated with an “evaluation as attractive” or “unified evaluation” is not observed evaluation as obvious. It appears that the number of places where refurbishment work is done needs to be increased for residents to recognize a rental premium.

-

2.

Comparison of rental premiums following indoor aesthetic work, indoor sound insulation work, equipment work, and external work

By adding indoor sound insulation to (1) above, males in their 20s recognized a rental premium, albeit limited (see Table 14.8).

A rental premium for dwellings that were refurbished 20 years after construction was recognized at the highest level for males in their 20s, estimated at 3.9%. The level was below 1.0% for age groups of 30s and above, which is a result that lacks economic value in terms of the rent increase rate. On the other hand, females in all age groups die not recognize a rental premium.

A rental premium for dwellings that were refurbished 40 years after construction was also recognized by males in their 20s, at 2.7%. This was 1.2% points below the level for 20 years after construction, suggesting the tendency for a rental premium decline with the number of years since construction (see Table 14.8). In addition, males in their 30s, like females, do not approve of a rental premium.

As in the above, the comparison of (1) above and (3) below indicates an increase in the number of places where refurbishment is requested has a positive impact on the rental premium (see Table 14.7). On this point, Cho and Takada (2015) note that large scale refurbishment is an important trigger when deciding to purchase and observed that the greater the increase in the number of places of refurbishment work the greater the increase in the residents’ utility. It is said that this is consistent with previous research.

-

3.

Comparison of the rental premium following indoor aesthetic work, indoor sound insulation work, indoor spatial work, equipment work, and external work

By adding indoor spatial work to (2) above, a rise in the rental premium is forecast. Males in their 20s indicated the highest rental premium for dwellings that undergo refurbishment 20 years after construction, estimated at 7.3%. (See Table 14.8). The value indicated by males in their 30s to 50s is only about 50% of those in their 20s. On the other hand, females estimate low values overall in comparison to the rental premiums of males in the same age group. Specifically, females in their 20s and 50s have a relatively high rental premium of 2.6% and 2.5% respectively. In addition, females in their 30s and 40% are estimated to both have levels below 2%.

For dwellings that were refurbished 40 years since constructions, as was similar thus far, a decline of about 1.2% points in the rental premium for all groups by gender and by age (see Table 14.8).

For males in their 20s, who recognized the highest rental premium, this is estimated to be 6.1%. In this regard, females in their 20s stopped at 1.4%. However, the lowest rental premium was recognized by females in their 30s and 40s with a rental premium below 1.0%, which is a result that lacks economic viability. For males in their 30s to 50s, the rental premium is estimated at 2.0% to 3.0%.

Therefore, this confirms that the number of years since construction has a negative impact on the rental premium for a dwelling.

Lastly, we add a study of the appropriateness of the estimation value of the rental premium.

For example, Harano et al. (2012) compare the transaction price for condominiums following large-scale refurbishment with the transaction price for those that have not been refurbished, pointing that they were 12.84% higher. Although the research target was not the rent, this is thought to have generated an appropriate result in estimation within the scope of such result.

7 Conclusion

An increase in rent following refurbishment is no doubt one requirement to indicate the economic rationality of undertaking refurbishment. Therefore, the measurement of rental premium that conforms to the refurbishment work is thought to be useful in the decision-making for undertaking such work.

Apart from residents’ gender and age having an impact on rental premium, the results also indicate that the exclusive floor area of the dwelling and the number of years since construction have an impact. In addition, it is important to note that rental residents’ level of satisfaction with the dwelling and sense of whether the current rent is expensive have a negative impact on the rental premium.

In increasing the ratio of investment impact from refurbishment, a well-planned execution would be desired that takes into consideration the floor area of the relevant dwelling and the number of years since construction as well as the gender and age of the occupants that all impact the rental premium.

Future issues for consideration would be to expand the target of refurbishment work to include earthquake resistance and energy-saving performance of the building and to measure their rental premiums.

Notes

- 1.

The questionnaire survey was designed to grasp the relationship between the state of functional sufficiency of the building and the degree of residents’ satisfaction by asking the question “How do you feel when refurbishment and/or renovation work is done?” with four options for the response: “like,” “feels natural,” “don’t feel anything,” and “it was not necessary.” In addition, a separate question asked, “How do you feel when refurbishment and/or renovation work is not done?” with four options for the response: “don’t like,” “can’t be helped,” “don’t feel anything,” and “it was not necessary.”

- 2.

Responses were obtained from the following question in relation to the rent premium. “If work is to be made that ‘you like,’ what maximum level of increase in monthly rent would you be willing to accept due to increased level of satisfaction compared to the current dwelling? Please respond by noting the maximum amount of increase in the rent you would be able to pay the owner. Note, when responding, please fully consider the rent level you are currently paying.”

- 3.

Statistical analysis software used R. Specifically, The MCMCtobit function of the MCM pack was used. The number of repeated calculations was taken to be 10,000 and the operation inspection period (burn-in) 1000. In addition, prior distribution was taken to be non-informative prior distribution.

- 4.

In regard to the estimates of rental premiums, residents’ anticipated annual income is taken to be the average wave by age group based on the National Tax Agency, “Statistical Survey of Actual Status for Salary in the Private Sector 2015,” September 2016. In addition, in regard to exclusive floor area, it was taken to be 45 m2 with reference to the total floor area per single rented house in the Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications, “2013 Housing and Land Survey.” Furthermore, in regard to the degree of expense concerning residents’ level of satisfaction in the dwelling and the current rent, the normal level is anticipated.

References

Cho H, Takada M (2015) Actual conditions of remodeling going with existing housing circulation and features of existing home buyers who assume remodeling. Architect Inst Jpn J Architect 80(712):1381–1390

Furutani T (2008) Bayesian statistics data analysis—R & Win BUGS. Asakura Publishing, Kanagawa, pp 95–99

Harano T, Nakagawa M, Shimizu C, Karawatari H (2012) The effect of asymmetric information in used housing market on renovated house prices. JCER Econ J 66:51–71

Iwata S, Yamaga H (2008) Empirical analysis of resale externality in used house market. Q Housing Land Econ 35:23–28

Kano N, Seraku N, Takahashi H, Tsuji S (1984) Attractive quality and must-be quality. Quality 14(2):39–48

Komatsu H, Chau Y (2015) Research on aging cost factor of apartment house using stated preference data of estate investor. Q Real Estate Res 57(4):52–64

Takagi K, Kashihara S, Yoshimura H, Yokota T, Sakata K, Nishioka E (2002) Remodeling and rebuilding of detached houses in Senri New Town—a study on remodeling methods for long life houses. Architect Inst Jpn J Architect 556:189–195

Terui N (2010) Bayesian statistics analysis using R. Asakura Publishing, Kanagawa, pp 91–95

Acknowledgments

I received valuable opinions from a reviewer which improved this paper. I take this opportunity to express my appreciation. In addition, this research was made possible with the research assistance from Daito Trust Construction Co., Ltd. I am deeply grateful.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Komatsu, H. (2021). Study on Premium Rent of Refurbished Apartments Based on Bayesian Modeling Using Stated Preference Data of the Tenants. In: Asami, Y., Higano, Y., Fukui, H. (eds) Frontiers of Real Estate Science in Japan. New Frontiers in Regional Science: Asian Perspectives, vol 29. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8848-8_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-8848-8_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN: 978-981-15-8847-1

Online ISBN: 978-981-15-8848-8

eBook Packages: Economics and FinanceEconomics and Finance (R0)