Abstract

Fruits and vegetables are vital for healthy diets, but intake remains low for a majority of the global population. This chapter reviews academic literature on food system issues, as well as opportunities for research and action, as an input into the 2021 UN Food Systems Summit in the context of the International Year of Fruits and Vegetables.

The chapter summarises evidence underpinning food system actions to make fruits and vegetables more available, accessible and desirable through push (production and supply), pull (demand and activism) and policy (legislation and governance) mechanisms, with action options at the macro (global and national), meso (institutional, city and community) and micro (household and individual) levels. It also suggests the need to recognise and address power disparities across food systems, and trade-offs among diet, livelihood and environmental food system outcomes.

We conclude that there is still a need to better understand the different ways that food systems can make fruits and vegetables available, affordable, accessible and desirable across places and over time, but also that we know enough to accelerate action in support of fruit- and vegetable-rich food systems that can drive healthy diets for all.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Why Fruits and Vegetables? Why Now?

Fruits and vegetables are vital for healthy diets, and there is broad consensus that a diverse diet containing a range of plant foods (and their associated nutrients, phytonutrients and fibre) is needed for health and wellbeing (FAO 2020). Studies have suggested intake ranges of 300–600 g per day (200–600 g of vegetables and 100–300 g of fruits) to meet different combinations of health and environmental goals (Willett et al. 2019; Loken et al. 2020; Afshin et al. 2019). The World Health Organisation (WHO) recommends that adults eat at least 400 g of fruits and vegetables per day (World Health Organisation 2003), with national food-based dietary guidelines translating these into recommendations to eat multiple portions of a variety of fruits and vegetables each day for health (Herforth et al. 2019).

Despite this clear message, intake of fruits and vegetables remains low for a majority of the global population (Afshin et al. 2019; Kalmpourtzidou et al. 2020). Low fruit and vegetable consumption is among the five main risk factors for poor health, with over 2 million deaths and 65 million Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) attributable to low intake of fruits, and 1.5 million deaths and 34 million DALYs attributable to low intake of vegetables globally each year, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Afshin et al. 2019). Low consumption is a global problem, affecting high- and low-income countries: only 7% of countries in Africa, 7% in the Americas, and 11% in Europe reach 240 g/day of vegetables on average (Kalmpourtzidou et al. 2020), and only 20% of individuals in low- and middle-income countries reach the recommendation of five servings of fruits and vegetables a day (Frank et al. 2019). The mean global intake of vegetables is estimated to be around 190 g/day, and of fruits, 81 g/day. Studies generally agree that parts of Africa and the Pacific Islands have the lowest fruit and vegetable consumption, and East Asia has the highest vegetable (but not fruit) consumption (Afshin et al. 2019; Kalmpourtzidou et al. 2020; Micha et al. 2015).

Changes in fruit and vegetable consumption are happening against a backdrop of the ‘nutrition transition’ from traditional foods to processed and ultra-processed foods that are high in energy, fat, sugar and salt, but poor in other essential nutrients (Popkin et al. 2020). This transition also brings opportunities to diversify into healthy diets containing more fresh fruits and vegetables, although, for some populations, there is less opportunity than for others (Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition 2016). The available literature does not suggest systematic differences in fruit and vegetable consumption between men and women in many contexts (Frank et al. 2019; Micha et al. 2015), but it does highlight differences in consumption between rural and urban areas (Hall et al. 2009; Ruel et al. 2004; Mayen et al. 2014), and among populations with different levels of education and national income (Frank et al. 2019). These differences illustrate that there is an equity issue across populations in accessing fruits and vegetables (Harris et al. 2021a).

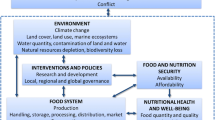

We now have good conceptual models for how food systems work to provide diets (HLPE 2017). These help us to describe the structural and social constraints to fruit and vegetable consumption and research how these play out in different contexts and for different populations. Below, we summarise what we know (and what we need to know) about how to address the issues above through a set of push (production and supply), pull (demand and activism) and policy (legislation and governance) actions. We conclude that there is still a need to better understand the different ways that food systems can make fruits and vegetables available, accessible, affordable and desirable for all people, across places and over time, so as to meet global recommendations, but also that we know enough to accelerate action in support of healthy diets. The year 2021 is the UN International Year of Fruits and Vegetables, embedded in the middle of the Decade of Action on Nutrition. Now is the time to prioritise understanding and addressing these issues to enable fruit- and vegetable-rich food systems that can drive healthy diets for all.

2 Policy Factors: Political Power

The Green Revolution in the latter part of the twentieth century transformed agriculture’s ability to produce sufficient calories to feed the world, but the focus on grain crops through funding, research, extension and technology development limited the supply of nutrient-dense fruits and vegetables, both through losses of wild sources with the promotion of monocultures and through policy and structural impediments that crowded out non-staple crops (Pingali 2012). Today, the combined international public research budget for maize, wheat, rice, and starchy tubers is 30 times greater than for vegetables, for instance (Herforth 2020), and these incentives skew many of the technology and infrastructure drivers of food systems. This has fed into national food policies, which are normally focused on the production or import of staple crops (as a source of cheap calories), rather than diet quality through diversity of fresh foods (as a source of other essential nutrients) (McDermott and De Brauw 2020). Following suit, food system data have focused largely on globally-tradable commodities, leading to a dearth of trustworthy and disaggregated data with which to track the production, price, trade or consumption of the diversity of fruits and vegetables (Masters et al. 2018), and global data are biased towards economically-relevant crops, often missing traditional fruits and vegetables and those produced non-commercially (Thar et al. 2020). Research on food systems and diets often treats fruits and vegetables as a single food group, rather than looking at diversity within fruit and vegetable species, or the amounts or variety consumed within the food group (Harris et al. 2021b), further limiting our knowledge on the specifics of issues or actions.

At the same time, large structural changes outside of the food system, such as the globalisation of supply chains and societies, and changing demographics and urbanisation have shaped food regimes to prioritise foods that are non-perishable and globally tradable (Magnan 2012; Lang and Heasman 2015), the very opposite of most fruits and vegetables, whose perishability requires shorter food chains from farm to fork. Modern trade rules improve regulation on the safety of imported fruits and vegetables and may protect domestic production or improve supply of highly-traded commodities, but they also limit the ability of governments to protect the public health policy space and the institutional purchase of fresh foods (Thow et al. 2015) and tend to prioritise staple foods over fruits and vegetables, while out-sourcing the environmental impacts of production to poor countries (FAO 2020). In many contexts, the concentration of inputs, distribution and retail of foods – including fruits and vegetables – in the hands of a few large companies, has shifted food system choices away from the livelihood interests of producers, the health interests of consumers, and the environmental interests of all (Howard 2016).

These broad and sweeping changes have not been without interruption: the COVID-19 pandemic and previous economic shocks and natural disasters have disrupted many aspects of food systems and diets over time (Savary et al. 2020; Block et al. 2004; Darnton-Hill and Cogill 2010). Such disruptions particularly affect fruits and vegetables because of their specific labour, storage and transport requirements (Harris 2020), with at least temporary impacts of different shocks having been documented on the livelihoods of fruit and vegetable producers and on fruit and vegetable prices and consumption (Block et al. 2004; Darnton-Hill and Cogill 2010; Harris et al. 2020; Hirvonen et al. 2020). These shocks have affected the diets and livelihoods of marginalised populations in ways different from those with economic or social power, further exacerbating inequity (Carducci et al. 2021; Kansiime et al. 2021; Goldin and Muggah 2020).

2.1 Opportunities for Research and Action

Each of these big-picture policy and political drivers has created food system ‘lock-ins’ (Leach et al. 2020), which have tended to steer away from pathways prioritising fruits and vegetables, and away from agronomic and food system paradigms – such as agroecology, a right to food, or food as a commons rather than a commodity (Rosset and Altieri 2017; Vivero-Pol et al. 2018; Patnaik and Oenema 2015) – that might promote a return to more diverse production systems. Policy decisions can start with evidence: we need to know more about how different production and distribution systems, based in different social and political traditions, drive the availability and accessibility of fruits and vegetables in food systems, and how they weather shocks to provide healthy diets sustainably and equitably. However, ultimately, while data and evidence can reveal nuance in the issues and their solutions, food policy decisions are political (and, ideally, ethical) in reality, depending on the priorities and tolerances of the actors involved in making those decisions (Harris 2019). Bringing together people with a stake in food systems to debate and decide policy, explicitly recognising disparities in power among them in contributing to outcome and decisions, is likely to lead to the most context-specific and equitable policy in practice when done well (Chaudhury et al. 2013; Barzola et al. 2019; Blay-Palmer et al. 2018).

A starting point for addressing the lack of fruits and vegetables in food system policy is ‘reverse thinking’, putting the dietary outcomes we want from food systems upfront in responsive food policy-making and legislation, and working towards incentivising systems that create these (McDermott and De Brauw 2020). A difficulty in achieving this vision is that different actor coalitions frame food system issues and priorities differently according to their interests and beliefs, so that there is no single narrative to work towards (Harris 2019; Béné et al. 2019), and coherent diet and food system policy will require policy sectors to work together in non-traditional ways (Thow et al. 2018). There is, therefore, a need to better understand how public and private decision-makers make food system choices and how other food system actors influence these, as well as the implications for fruits and vegetables across food systems.

Public investment in agriculture is shown to impact the growth of production through the private sector, but different types of investment produce different results for different foods in different contexts (Mogues et al. 2012), so we need to know more about how specific investments, such as in breeding, production subsidies, and extension support, play out in food environments for different fruits and vegetables. Acknowledging the imbalance of power among food system actors, illustrated by disparities between budgets of processed food producers (Baker et al. 2020) and public investment in healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables (Herforth 2020), is necessary in order to make transparent and health-positive policy, regulation and investment. Public policy shaping food environments – such as mandating vegetables in institutional meals (schools, workplaces, hospitals), setting incentives for healthy retail, and regulating food system actors (Knai et al. 2006; Micha et al. 2018; Vandevijvere et al. 2019) – is seen to improve intakes in some contexts. Similarly, land rights are a key issue for sustainable food access and production (Sunderland and Vasquez 2020), and we need to know more about how these issues affect fruits and vegetables. For all of these analyses, better data and contextual knowledge on diverse fruits and vegetables in different systems is needed, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, to inform businesses, policy-makers, practitioners, workers and activists in making decisions within food systems.

3 Push Factors: Production and Post-Harvest Power

By the data we have, global fruit and vegetable production is insufficient to meet the WHO dietary recommendations, and has been since global records began: in 1965, sufficient fruits and vegetables (≥400 g/day) were available for 17% of the global population, increasing to 55% in 2015 (Mason-D’Croz et al. 2019). Supply varies widely between contexts: in Africa, only 13% of countries have an adequate aggregate vegetable supply, while in Asia, 61% do (Kalmpourtzidou et al. 2020). This is despite the fact that fruits and vegetables are valuable: the annual farmgate value of global fruit and vegetable production is nearly $1 trillion and exceeds the farmgate value of all food grains combined (US$ 837 billion) (Schreinemachers et al. 2018). Most fruits and vegetables (about 92%) are not internationally traded, but the international trade in fruits and vegetables was still valued at US$ 138 billion in 2018.

Fruit and vegetable production needs to increase, particularly in regions with low consumption, together with accompanying measures to prevent losses, to provide enough for healthy diets (Mason-D’Croz et al. 2019). Scaling production is not straightforward, as fruits and vegetables have specific attributes – in terms of seasonal and agro-climatic differences, labour and input needs, knowledge and expertise, and storage and distribution – that mean there are particular trade-offs to consider. While we can, in theory, produce healthy diets within planetary boundaries (Willett et al. 2019), achieving national food-based dietary guidelines has been found to be incompatible with climate and environmental targets in a majority of the 85 countries studied (Springmann et al. 2020), and producing more fruits and vegetables may require more land, water and chemical inputs than producing staple foods in some contexts (Aleksandrowicz et al. 2016), with one-third of all greenhouse gas emissions being produced by the food system (Crippa et al. 2021). Various studies show widespread misuse of agricultural chemicals, particularly on high-value vegetables, creating hazards for farm workers, consumers and the environment (Schreinemachers et al. 2020a). Foodborne diseases caused by biological contamination of food are also an important threat to public health, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, and fruits and vegetables are among the riskiest foods for biological hazards (Grace 2015).

Seed or planting stock is a key input in fruit and vegetable production, although it is a contested area: some see the introduction of (often proprietary) improved varieties of fruits and vegetables as necessary to transform the fruit and vegetable sector to one with increased volumes of regularly available quality products (Schreinemachers et al. 2018; Dawson et al. 2019; Schreinemachers et al. 2021; Lillesø et al. 2018). Others stress the importance of local or cultural seed-saving and exchange of planting material for conserving farmers’ independence, agricultural diversity and food sovereignty (Howard 2016; Phillips 2016), and debates about the primacy of breeders’ rights or farmers’ rights are ongoing (Gupta and Negi 2019; Salazar et al. 2007; Dias 2011). Beyond inputs, labour requirements in fruit and vegetable production are considerably higher than in cereal production, with labour costs making up more than 50% of production costs, depending on the food grown, related to more skilled and intensive field operations (Weinberger and Lumpkin 2007; Herrero et al. 2017). This is a positive for food system worker incomes, but extension services are often geared towards staple crops, with little support for fruit and vegetable producers, limiting formal training opportunities (Pingali 2015). Beyond the farm, post-farmgate midstream employment in developing regions constitutes roughly 20% of rural employment (Dolislager et al. 2020; Reardon et al. 2014). It is assumed that many smallholders also engage in midstream fruit and vegetable chain operations, such as trade and processing, but fruit and vegetable value chains have not been a focus of this work, so more knowledge is needed in this area.

Of food produced for human consumption, around one-third by volume or one-quarter by calories is either lost (before retail) or wasted (after purchase) (HLPE 2014). Highly perishable fruits and vegetables have the highest rates of loss and waste, usually within the range of 40–50% (Global Panel 2018; FAO 2019). Local production is therefore central, and in many contexts, ultra-local home-based fruit and vegetable production and wild plant gathering are important strategies (Schreinemachers et al. 2015; Bharucha and Pretty 2010), as are ‘under-utilised’ species and many traditional fruits and vegetables that are often left out of data, policy and extension (Raihana et al. 2015; Hunter et al. 2019). Fruits and vegetables are particularly seasonal, which can be an advantage in diverse systems where different foods become available at different times, or a challenge where there are gluts and shortages that lead to price changes over the course of the year (Gilbert et al. 2017; McMullin et al. 2019).

3.1 Opportunities for Research and Action

Clearly, greater availability of a variety of fruits and vegetables is needed for everyone to meet recommendations. This can be achieved through increased production, although there are trade-offs between environmental sustainability and providing for diets: sustainable intensification using a wide range of approaches according to the social, political and agro-ecological contexts to improve yields or protect against climate changes without environmental degradation has been suggested (Schreinemachers et al. 2018; Godfray and Garnett 2014), although further understanding of the implications of different approaches to fruit and vegetable production is needed. Organic agriculture meets goals for a range of environmental factors, including reduced chemical contamination of diets, but it has weaknesses in terms of lower productivity and reduced yield stability (Knapp and van der Heijden 2018), and the subsidisation of chemical inputs makes it appear less profitable. Supporting the availability of planting material through formal (breeding and seed companies) and informal (seed-saving and sharing networks) channels is important (Schreinemachers et al. 2018).

The economic value of fruits and vegetables is a strong incentive for their production, but much of this value is captured by large global firms rather than smallholders, despite over 80% of fruit and vegetables being grown on smallholder family farms (<20 ha) in LMICs (Herrero et al. 2017). The smallholder nature of many fruit and vegetable producers and traders provides challenges and opportunities for vegetable supply (Reardon and Timmer 2014), and the complexity of systems of traders and the heterogeneity of smallholders and their support needs (particularly peri-urban vegetable producers or women, who may not be engaged in formal extension systems (FAO 2021; Fischer et al. 2017)) means that agricultural policy very often does not adequately support the twin goals of healthy food production and livelihood development (Gassner et al. 2019). Aggregation or contract farming is commonly used to reduce transaction costs and risk, and to sell to modern channels such as supermarkets, where demand for fruits and vegetables is growing (Reardon et al. 2012; Holtland 2017), although the impacts of commercialisation on the diets of commercial farmers themselves are mixed (Carletto et al. 2017). Farmer extension needs to be strengthened (Schreinemachers et al. 2018), and we need more documented understanding of how informal sectors and formal small and medium enterprises involved in fruit and vegetable processing, distribution and retail can deliver more on desired food system outcomes. These need further research to understand how they play out in fruit and vegetable systems.

Better availability can also be achieved by addressing food loss and waste: in low-income countries, through addressing on-farm pests and diseases, pre-maturity harvesting due to climate shocks or seasonal gluts, and inappropriate post-harvest handling, transport and storage, and in middle-/high-income countries, by addressing quality grading standards set by retailers (Global Panel 2018). Packaging of perishable fruits and vegetables can limit losses (Wohner et al. 2019), but also contributes to environmental pollution and greenhouse gas emissions (Crippa et al. 2021; Yates et al. 2021). More understanding is needed of the production, processing and distribution options and trade-offs, and of food loss and waste, specifically for fruits and vegetables in different contexts.

The physical availability of food varies, depending on functioning supply chains, whether short or long. Food deserts and swamps associated with poorer diets occur where there is a lack of available fresh foods for local purchase, and exist particularly in poorer urban areas (Ghosh-Dastidar et al. 2014). Physical access is a key driver of purchase (and, by extension, consumption), with a lack of fresh food outlets making consumption of fresh produce harder (Beaulac et al. 2009), and, conversely, living close to vegetable vendors making vegetable purchase more likely (Ambikapathi et al. 2021), suggesting that local access options are important in shaping diets.

4 Pull Factors: People Power

While availability of, and physical access to, sufficient fruits and vegetables is an important prerequisite, there are other factors at the socio-economic and personal levels that also impact their role in diets. Reviews of research suggest that, in low-income countries, similar determinants play a role in food choices as in high-income countries, at the individual level (income, employment, education level, food knowledge, lifestyle, time), in the social environment (family and peer influence, cultural factors), and in the physical environment (food expenditure, lifestyle) (Gissing et al. 2017).

Food prices interact with incomes to determine whether households can afford the components of a healthy diet, and fruits and vegetables, along with animal-source foods, are the most expensive element of a healthy diet, comprising, by many metrics (Maillot et al. 2007; Headey and Alderman 2019), around 40% of the cost of a healthy diet (Herforth et al. 2020), although these costs tend to vary with the season (Gilbert et al. 2017). Fruits and vegetables are unaffordable for many, with 3 billion people unable to afford diverse, healthy diets (Herforth et al. 2020). Fruits and vegetables appear more affordable when comparing prices per micronutrient, according to which they are likely to be a relatively low-cost source of varied vitamins, minerals, and phytonutrients (Drewnowski 2013), but this is not how most families choose their food.

Beyond a certain income level, affordability is not a driving factor for everyone everywhere: while an increase of fruit and vegetable consumption by income across geographical regions is confirmed in many studies, indicating that a low income is a barrier to fruit and vegetable consumption for some (Frank et al. 2019; Miller et al. 2016), there is only a weak association between incomes and fruit and vegetable consumption, showing that, on average (across 52 countries), 82% of the poorest quintile consume an insufficient amount of fruits and vegetables and 73% of the wealthiest quintile do the same (Hall et al. 2009). As incomes rise, the consumption of meat, dairy and ultra-processed foods rises much faster than that of vegetables; additionally, the purchase of vegetables in some contexts changes little across income groups, and hence vegetable consumption is relatively inelastic to income past a certain level (Ruel et al. 2004), although a greater amount of fruit may be consumed at higher incomes. With little change in the consumption of vegetables across income groups in some contexts (Morris and Haddad 2020), affordability is not the largest driver of consumption for all.

Even if vegetables are available, accessible and affordable, most people still do not consume large enough quantities (Hall et al. 2009), particularly if they are not considered an acceptable or desirable food choice, for instance, due to food safety or contamination concerns, taste preferences, or cultural appropriateness (Aggarwal et al. 2016; Ha et al. 2020; Hammelman and Hayes-Conroy 2014). Low desirability of fruits and vegetables is a particular problem among children and adolescents, with data across 73 countries showing that between 10% and 30% of students do not eat any vegetables at all in one-quarter of these countries (FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO 2019).

4.1 Opportunities for Research and Action

Addressing the affordability of fruits and vegetables is key to creating an environment where all can access a healthy diet, and affordability can come from a combination of lower retail prices (through productivity improvements, reduced post-harvest losses, or increased market efficiency for stable prices) and higher incomes (from inclusive economic growth and social safety nets) (Hirvonen et al. 2019). Cheap food is not necessarily good for healthy diets, fair livelihoods or biodiverse environments, so a focus on raising people up through fair wages is important (Benton et al. 2021). Price subsidies for fruits and vegetables is a policy option that is popular with the public in some contexts (Niebylski et al. 2015), and there is evidence that price incentives to make fruits and vegetables more directly affordable have worked to increase consumption (Swinburn et al. 2019; Olsho et al. 2016). These affordability interventions in contexts where a majority of fruits and vegetables are purchased can be combined with non-purchase interventions such as promoting home and community production or the facilitation of foraging where the context allows (Schreinemachers et al. 2016; Baliki et al. 2019; Powell et al. 2015).

Alongside the ability to afford fruits and vegetables, the challenge is to enhance consumer choice of and preference for these foods. There is clear evidence that focusing on education at all levels is a key component for modifying behavioural changes in general (Alderman and Headey 2017), and nutrition literacy, social norms for healthy eating, and self-efficacy are key components of health-related behavioural change (Eker et al. 2019), although we know less in regard to fruits and vegetables in particular. Nutrition literacy programmes generally target women, who are custodians of household nutrition in many contexts, but there may also be a need for community-targeted messages to change social norms (Van den Bold et al. 2013). Promoting traditional or under-utilised vegetables that are familiar was seen as a key policy option for healthy diets and environmental sustainability among the members of an expert opinion Delphi panel (Pedersen et al. 2020), and the latest generation of food-based dietary guidelines have begun to move in this direction, but these efforts need to better consider cultural acceptability and may require promotional efforts to increase the willingness of consumers to shift their tastes to new or forgotten foods (Davis et al. 2021). Food composition data is lacking for many indigenous species, limiting the opportunity to develop appropriate nutritional messaging and promote wider use (Stadlmayr et al. 2013; Jansen et al. 2020).

Beyond appeals to public health, better understanding is required of consumers’ preferences and behaviours with respect to these foods and what kinds of incentives might promote more consumption in different contexts. Strategic placement of fruit and vegetables in retail outlets is found to have a moderately significant effect on increasing fruit or vegetable servings (Broers et al. 2017), and early exposure to fruits and vegetables through schools may shape future preferences for healthier diets (Schreinemachers et al. 2020b). Marketing is a key factor shaping desirability, but is consistently applied for ‘hedonic’ (processed) rather than ‘healthy’ (nutrient-dense) foods (Bublitz and Peracchio 2015). On marketing issues, much is known about high-income countries (Thomson and Ravia 2011), but less about low- and middle-income contexts where these approaches (understanding market segments and speaking to issues of desirability, aspiration, emotion and imagination) can be adapted for fruits and vegetables (Deo and Monterrosa 2020).

5 Fruit and Vegetable Food Systems: What Next?

The brief review above has laid out evidence on the key food system issues for fruits and vegetables in healthy diets, and, where available, included evidence on actions to address these. From this summary, it is clear that we know, on a broad scale, the structural limitations to fruits and vegetables: global and national challenges of increasing production and accessing quality growing material shared equitably, local issues of ensuring affordability, addressing perishability and enabling everyone everywhere to access fruits and vegetables, and social issues of valuing vegetables for their role in cuisines and for health. It is also clear that the precise issues and solutions to these vary by population and according to the food system context, and that there are multiple potential routes towards solutions that sometimes clash on ideals. Food system actions to make fruits and vegetables more available, affordable, accessible and desirable through policy, push and pull mechanisms comprise various options working at the macro (global and national), meso (institutional, city and community) and micro (household and individual) levels. Examples of actions from the review above are laid out in the table below.

It is unlikely that these are all of the options available for orienting food systems towards fruit- and vegetable-rich diets, but these are the options that appear in the academic literature, albeit with varying levels of evidence. In addition, there are two important over-arching considerations when considering action options: (1) Acknowledging that power shapes food systems, from the concentration of economic and political power in a few global agri-food businesses to the marginalisation of certain groups in societies from accessing healthy diets, so this needs to be considered in terms of both facilitating inclusive processes for deciding policies and actions and assessing their equity impacts (Howard 2016; Harris and Nisbett 2018); and (2) there will be trade-offs among food system outcomes, so starting with a focus on healthy diets is important, but understanding how food system decisions then impact fair livelihoods and sustainable environments is key (Wiebe and Prager 2021). We do not yet know enough to formulate clear actions that will address these trade-offs, but they need to be acknowledged and openly debated by those making food system decisions.

Examples of Policy, Push and Pull Actions at Different Levels

Macro (global and national) | Meso (institutional, city and community) | Micro (household and individual) | |

|---|---|---|---|

Policy | R&D investment Right to food legislation Food safety regulation | Zoning and marketing regulation Prioritising fruit and vegetables (F&V) in institutional food procurement plans | Protected foraging rights Land rights |

Push | Production subsidies Efficiency through breeding and technology Support for diverse alternative production paradigms Infrastructure development Fair finance access | Quality F&V planting material (formal and informal systems) Pre- and post-harvest practices and packaging Improving market access, shortening food supply chains F&V extension and training Support for fresh food outlets | Home & community gardens |

Pull | Price subsidies Social safety nets Food-based dietary guidelines | F&V-rich institutional meals Basic processing for preservation Social marketing campaigns Promotion of traditional F&V F&V product placement in shops and canteens | Nutrition literacy campaigns School gardens and learning for shaping preferences |

These actions are likely to be foundational to creating change within food systems towards enabling fruit- and vegetable-rich diets. None of these actions will change diets when implemented alone, but rather packages of actions need to be assembled to address particular limitations for fruit and vegetable consumption. These need to be considered in context, in light of an understanding of food system issues and bottlenecks limiting healthy diets in different places and for different people. It is likely that the best way to start is to bring together diverse groups of people interested in these issues at the different levels, to understand the issues and options from different perspectives and to prioritise together which actions should be undertaken first in their own context. This is not easy, given inherent power disparities among interested parties, but with care and inclusion, a strategy, policy or plan can be crafted to move towards enabling fruit and vegetable-rich food systems.

To guide better action, we need more evidence and understanding. We know a lot about a small fraction of the fruit and vegetable species of which we are aware, and very little about the rest. We know that there are disparities in diets in different contexts, but not how to address the political, social and equity determinants of who gets to eat fruits and vegetables. We know much about the technical production and market aspects of fruits and vegetables, but less about bottlenecks in bringing these to low- and middle-income countries, and we do not know enough about how these things change with context or over time. Work drawing on different academic traditions, including valuing traditional and tacit knowledge, is needed to connect the dots. Food systems that enable fruits and vegetables in healthy diets are not only a technical issue, but bring up very real political, social and ethical questions that societies will have to address, alongside a reliance on evidence. Having these conversations through the lens of equity to address the needs of both winners and losers within changing food systems will be a vital part of the UNFSS process towards enabling fruit and vegetable-rich food systems for healthy diets for all.

References

Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA et al (2019) Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 393(10184):1958–1972. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30041-8

Aggarwal A, Rehm CD, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A (2016) Importance of taste, nutrition, cost and convenience in relation to diet quality: evidence of nutrition resilience among US adults using National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2007–2010. Prev Med 90:184–192

Alderman H, Headey DD (2017) How important is parental education for child nutrition? World Dev 94:448–464

Aleksandrowicz L, Green R, Joy EJ, Smith P, Haines A (2016) The impacts of dietary change on greenhouse gas emissions, land use, water use, and health: a systematic review. PLoS One 11(11):e0165797

Ambikapathi R, Shively G, Leyna G et al (2021) Informal food environment is associated with household vegetable purchase patterns and dietary intake in the DECIDE study: empirical evidence from food vendor mapping in peri-urban Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Glob Food Secur 28:100474

Baker P, Machado P, Santos T et al (2020) Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev 21(12):e13126

Baliki G, Brück T, Schreinemachers P, Uddin MN (2019) Long-term behavioural impact of an integrated home garden intervention: evidence from Bangladesh. Food Secur 11:1217–1230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-019-00969-0

Barzola CL, Dentoni D, Allievi F et al (2019) Challenges of youth involvement in sustainable food systems: lessons learned from the case of farmers’ value network embeddedness in Ugandan Multi-Stakeholder Platforms. In: Achieving the Sustainable Development Goals through sustainable food systems. Springer, Cham, pp 113–129

Beaulac J, Kristjansson E, Cummins S (2009) A systematic review of food deserts, 1966–2007. Prev Chronic Dis 6(3)

Béné C, Oosterveer P, Lamotte L et al (2019) When food systems meet sustainability – current narratives and implications for actions. World Dev 113:116–130

Benton TG, Bieg C, Harwatt H, Pudasaini R, Wellesley L (2021) Food system impacts on biodiversity loss. Research paper: Energy, Environment and Resources Programme

Bharucha Z, Pretty J (2010) The roles and values of wild foods in agricultural systems. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 365(1554):2913–2926

Blay-Palmer A, Santini G, Dubbeling M, Renting H, Taguchi M, Giordano T (2018) Validating the city region food system approach: enacting inclusive, transformational city region food systems. Sustainability 10(5):1680

Block SA, Kiess L, Webb P et al (2004) Macro shocks and micro outcomes: child nutrition during Indonesia’s crisis. Econ Hum Biol 2(1):21–44

Broers VJ, De Breucker C, Van den Broucke S, Luminet O (2017) A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of nudging to increase fruit and vegetable choice. Eur J Public Health 27(5):912–920

Bublitz MG, Peracchio LA (2015) Applying industry practices to promote healthy foods: an exploration of positive marketing outcomes. J Bus Res 68(12):2484–2493

Carducci B, Keats E, Ruel M, Haddad L, Osendarp S, Bhutta Z (2021) Food systems, diets and nutrition in the wake of COVID-19. Nature Food 2(2):68–70

Carletto C, Corral P, Guelfi A (2017) Agricultural commercialization and nutrition revisited: empirical evidence from three African countries. Food Policy 67:106–118

Chaudhury M, Vervoort J, Kristjanson P, Ericksen P, Ainslie A (2013) Participatory scenarios as a tool to link science and policy on food security under climate change in East Africa. Reg Environ Chang 13(2):389–398

Crippa M, Solazzo E, Guizzardi D, Monforti-Ferrario F, Tubiello F, Leip A (2021) Food systems are responsible for a third of global anthropogenic GHG emissions. Nature Food:1–12

Darnton-Hill I, Cogill B (2010) Maternal and young child nutrition adversely affected by external shocks such as increasing global food prices. J Nutr 140(1):162S–169S

Davis KF, Downs S, Gephart JA (2021) Towards food supply chain resilience to environmental shocks. Nature Food 2(1):54–65

Dawson IK, Powell W, Hendre P et al (2019) The role of genetics in mainstreaming the production of new and orphan crops to diversify food systems and support human nutrition. New Phytol 224(1):37–54

Deo A, Monterrosa E (2020) Demand creation at GAIN

Dias JCS (2011) Biodiversity and vegetable breeding in the light of developments in intellectual property rights. Ecosyst Biodivers:389–428

Dolislager M, Reardon T, Arslan A et al (2020) Youth and adult agrifood system employment in developing regions: rural (peri-urban to hinterland) vs. urban. J Dev Stud:1–23

Drewnowski A (2013) New metrics of affordable nutrition: which vegetables provide most nutrients for least cost? J Acad Nutr Diet 113(9):1182–1187

Eker S, Reese G, Obersteiner M (2019) Modelling the drivers of a widespread shift to sustainable diets. Nature Sustain 2(8):725–735

FAO (2019) Moving forward on food loss and waste reduction. The State of Food and Agriculture

FAO (2020). The state of food security and nutrition in the world. Food and Agriculture Organisation

FAO (2021) Fruit and vegetables – your dietary essentials. The International Year of Fruits and Vegetables 2021 – Background paper. http://www.fao.org/3/cb2395en/CB2395EN.pdf

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, WHO (2019) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2019. Safeguarding against economic slowdowns and downturns, FAO

Fischer G, Gramzow A, Laizer A (2017) Gender, vegetable value chains, income distribution and access to resources: insights from surveys in Tanzania. Eur J Hortic Sci 82(6):319–327

Frank SM, Webster J, McKenzie B et al (2019) Consumption of fruits and vegetables among individuals 15 years and older in 28 low-and middle-income countries. J Nutr 149(7):1252–1259

Gassner A, Harris D, Mausch K et al (2019) Poverty eradication and food security through agriculture in Africa: rethinking objectives and entry points. Outlook Agric 48(4):309–315

Ghosh-Dastidar B, Cohen D, Hunter G et al (2014) Distance to store, food prices, and obesity in urban food deserts. Am J Prev Med 47(5):587–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2014.07.005

Gilbert CL, Christiaensen L, Kaminski J (2017) Food price seasonality in Africa: measurement and extent. Food Policy 67:119–132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2016.09.016

Gissing SC, Pradeilles R, Osei-Kwasi HA, Cohen E, Holdsworth M (2017) Drivers of dietary behaviours in women living in urban Africa: a systematic mapping review. Public Health Nutr 20(12):2104–2113

Global Panel (2018) Preventing nutrient loss and waste across the food system: policy actions for high-quality diets. Policy brief no. 12

Global Panel on Agriculture and Food Systems for Nutrition (2016) Food systems and diets: Facing the challenges of the 21st century. http://www.glopan.org/foresight

Godfray HCJ, Garnett T (2014) Food security and sustainable intensification. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci 369(1639):20120273

Goldin I, Muggah R (2020) COVID-19 is increasing multiple kinds of inequality. Here’s what we can do about it

Grace D (2015) Food safety in low and middle income countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12(9):10490–10507

Gupta A, Negi P (2019) Protection of ‘plant varieties’ vs. balancing of rights of breeders and farmers. Int J Rev Res Soc Sci 7(4):741–745

Ha TM, Shakur S, Pham Do KH (2020) Risk perception and its impact on vegetable consumption: a case study from Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clean Prod 271:122793

Hall JN, Moore S, Harper SB, Lynch JW (2009) Global variability in fruit and vegetable consumption. Am J Prev Med 36(5):402–409.e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.01.029

Hammelman C, Hayes-Conroy A (2014) Understanding cultural acceptability for urban food policy. J Plan Literat 30(1):37–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0885412214555433

Harris J (2019) Coalitions of the willing? Advocacy coalitions and the transfer of nutrition policy to Zambia. Health Policy Plan 34(3):207–215

Harris J (2020) Diets in a time of coronavirus: don’t let vegetables fall off the plate. IFPRI Covid-19 blogs blog. April 13, 2020. https://www.ifpri.org/blog/diets-time-coronavirus-dont-let-vegetables-fall-plate

Harris J, Nisbett N (2018) Equity in social and development studies research: what insights for nutrition? SCN News 43

Harris J, Depenbusch L, Pal AA, Nair RM, Ramasamy S (2020) Food system disruption: initial livelihood and dietary effects of COVID-19 on vegetable producers in India. Food Secur 12(4):841–851

Harris J, Tan W, Mitchell B, Zayed D (2021a) Equity in agriculture-nutrition-health research: a scoping review. Nutr Rev 80:78

Harris J, Tan W, Raneri J, Schreinemachers P, Herforth A (2021b) Vegetables in food systems for healthy diets in low- and middle-income countries: mapping the literature. Food Nutr Bull 43:232

Headey DD, Alderman HH (2019) The relative caloric prices of healthy and unhealthy foods differ systematically across income levels and continents. J Nutr. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxz158

Herforth A (2020) Three billion people cannot afford a healthy diet: What does this mean for the next Green Revolution? Center for Strategic and International Studies commentary blog. September 23, 2020. https://www.csis.org/analysis/three-billion-people-cannot-afford-healthy-diets-what-does-mean-next-green-revolution

Herforth A, Arimond M, Álvarez-Sánchez C, Coates J, Christianson K, Muehlhoff E (2019) A global review of food-based dietary guidelines. Adv Nutr 10(4):590–605

Herforth A, Bai Y, Venkat A, Mahrt K, Ebel A, Masters W (2020) Cost and affordability of healthy diets across and within countries: background paper for The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. FAO Agricultural Development Economics Technical Study No. 9, vol 9. Food & Agriculture Organisation

Herrero M, Thornton PK, Power B et al (2017) Farming and the geography of nutrient production for human use: a transdisciplinary analysis. Lancet Planet Health 1(1):e33–e42

Hirvonen K, Bai Y, Headey D, Masters WA (2019) Cost and affordability of the EAT-Lancet diet in 159 countries. Lancet

Hirvonen K, Mohammed B, Minten B, Tamru S (2020) Food marketing margins during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from vegetables in Ethiopia, vol 150. International Food Policy Research Institute, Washington, DC

HLPE (2014) Food losses and waste in the context of sustainable food systems. High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition of the Committee on World Food Security

HLPE (2017) Nutrition and food systems

Holtland G (2017) Contract farming in Ethiopia: concept and practice. AgriProFocus

Howard PH (2016) Concentration and power in the food system: who controls what we eat? vol 3. Bloomsbury Publishing, London

Hunter D, Borelli T, Beltrame DM et al (2019) The potential of neglected and underutilized species for improving diets and nutrition. Planta 250(3):709–729

Jansen M, Guariguata MR, Raneri JE et al (2020) Food for thought: the underutilized potential of tropical tree-sourced foods for 21st century sustainable food systems. People Nature 2(4):1006–1020

Kalmpourtzidou A, Eilander A, Talsma EF (2020) Global vegetable intake and supply compared to recommendations: a systematic review. Nutrients 12(6):1558

Kansiime MK, Tambo JA, Mugambi I, Bundi M, Kara A, Owuor C (2021) COVID-19 implications on household income and food security in Kenya and Uganda: findings from a rapid assessment. World Dev 137:105199

Knai C, Pomerleau J, Lock K, McKee M (2006) Getting children to eat more fruit and vegetables: a systematic review. Prev Med 42(2):85–95

Knapp S, van der Heijden MG (2018) A global meta-analysis of yield stability in organic and conservation agriculture. Nat Commun 9(1):1–9

Lang T, Heasman M (2015) Food wars: the global battle for mouths, minds and markets. Routledge, London

Leach M, Nisbett N, Cabral L, Harris J, Hossain N, Thompson J (2020) Food politics and development. World Dev 134:105024

Lillesø J-PB, Harwood C, Derero A et al (2018) Why institutional environments for agroforestry seed systems matter. Dev Policy Rev 36:O89–O112

Loken B, Opperman J, Orr S et al (2020) Bending the curve: the restorative power of planet-based diets. WWF Food Practice

Magnan A (2012) Food regimes. In: The Oxford handbook of food history, pp 370–388

Maillot M, Darmon N, Darmon M, Lafay L, Drewnowski A (2007) Nutrient-dense food groups have high energy costs: an econometric approach to nutrient profiling. J Nutr 137(7):1815–1820. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/137.7.1815

Mason-D’Croz D, Bogard JR, Sulser TB et al (2019) Gaps between fruit and vegetable production, demand, and recommended consumption at global and national levels: an integrated modelling study. Lancet Planet Health 3(7):e318–e329

Masters WA, Bai Y, Herforth A et al (2018) Measuring the affordability of nutritious diets in Africa: price indexes for diet diversity and the cost of nutrient adequacy. Am J Agric Econ 100(5):1285–1301

Mayen A-L, Marques-Vidal P, Paccaud F, Bovet P, Stringhini S (2014) Socioeconomic determinants of dietary patterns in low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr 100(6):1520–1531

McDermott J, De Brauw A (2020) National food systems: inclusive transformation for healthier diets. IFPRI book chapters, pp 202054–202065

McMullin S, Njogu K, Wekesa B et al (2019) Developing fruit tree portfolios that link agriculture more effectively with nutrition and health: a new approach for providing year-round micronutrients to smallholder farmers. Food Secur 11(6):1355–1372

Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Andrews KG, Engell RE, Mozaffarian D (2015) Global, regional and national consumption of major food groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis including 266 country-specific nutrition surveys worldwide. BMJ Open 5(9):e008705

Micha R, Karageorgou D, Bakogianni I et al (2018) Effectiveness of school food environment policies on children’s dietary behaviors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 13(3):e0194555

Miller V, Yusuf S, Chow CK et al (2016) Availability, affordability, and consumption of fruits and vegetables in 18 countries across income levels: findings from the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study. Lancet Glob Health 4(10):e695–e703. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(16)30186-3

Mogues T, Yu B, Fan S, McBride L (2012) The impacts of public investment in and for agriculture: synthesis of the existing evidence

Morris S, Haddad L (2020) Selling to the world’s poorest – the potential role of markets in increasing access to nutritious foods. GAIN working paper series 14

Niebylski ML, Redburn KA, Duhaney T, Campbell NR (2015) Healthy food subsidies and unhealthy food taxation: a systematic review of the evidence. Nutrition 31(6):787–795

Olsho LE, Klerman JA, Wilde PE, Bartlett S (2016) Financial incentives increase fruit and vegetable intake among Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program participants: a randomized controlled trial of the USDA Healthy Incentives Pilot. Am J Clin Nutr 104(2):423–435

Patnaik B, Oenema S (2015) The human right to nutrition security in the post-2015 development agenda. SCN News 41:69–73

Pedersen C, Remans R, Zornetzer H, et al (2020) Game-changing innovations for healthy diets on a healthy planet: Insights from a Delphi Study

Phillips C (2016) Saving more than seeds: practices and politics of seed saving. Routledge, London

Pingali PL (2012) Green revolution: impacts, limits, and the path ahead. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(31):12302–12308

Pingali P (2015) Agricultural policy and nutrition outcomes – getting beyond the preoccupation with staple grains. Food Secur 7(3):583–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-015-0461-x

Popkin BM, Corvalan C, Grummer-Strawn LM (2020) Dynamics of the double burden of malnutrition and the changing nutrition reality. Lancet 395(10217):65–74

Powell B, Thilsted SH, Ickowitz A, Termote C, Sunderland T, Herforth A (2015) Improving diets with wild and cultivated biodiversity from across the landscape. Food Secur 7(3):535–554

Raihana AN, Marikkar J, Amin I, Shuhaimi M (2015) A review on food values of selected tropical fruits’ seeds. Int J Food Prop 18(11):2380–2392

Reardon T, Timmer CP (2014) Five inter-linked transformations in the Asian agrifood economy: food security implications. Glob Food Secur 3(2):108–117

Reardon T, Chen KZ, Minten B, Adriano L (2012) The quiet revolution in staple food value chains in Asia: enter the dragon, the elephant, and the tiger. Asian Development Bank and International Food Policy Research Institute, Manila

Reardon T, Tschirley D, Dolislager M, Snyder J, Hu C, White S (2014) Urbanization, diet change, and transformation of food supply chains in Asia. Global Centre for Food Systems Innovation

Rosset PM, Altieri MA (2017) Agroecology: science and politics. Practical Action Publishing, Warwickshire

Ruel MT, Nicholas M, Lisa S (2004) Patterns and determinants of fruit and vegetable consumption in sub-Saharan Africa. FAO/WHO workshop on fruits and vegetables for health

Salazar R, Louwaars NP, Visser B (2007) Protecting farmers’ new varieties: new approaches to rights on collective innovations in plant genetic resources. World Dev 35(9):1515–1528

Savary S, Akter S, Almekinders C et al (2020) Mapping disruption and resilience mechanisms in food systems. Food Secur 12(4):695–717

Schreinemachers P, Patalagsa MA, Islam MR et al (2015) The effect of women’s home gardens on vegetable production and consumption in Bangladesh. Food Secur 7(1):97–107

Schreinemachers P, Patalagsa MA, Uddin N (2016) Impact and cost-effectiveness of women’s training in home gardening and nutrition in Bangladesh. J Dev Effect 8(4):473–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/19439342.2016.1231704

Schreinemachers P, Simmons EB, Wopereis MC (2018) Tapping the economic and nutritional power of vegetables. Glob Food Secur 16:36–45

Schreinemachers P, Grovermann C, Praneetvatakul S et al (2020a) How much is too much? Quantifying pesticide overuse in vegetable production in Southeast Asia. J Clean Prod 244:118738

Schreinemachers P, Baliki G, Shrestha RM et al (2020b) Nudging children toward healthier food choices: an experiment combining school and home gardens. Glob Food Secur 26:100454

Schreinemachers P, Howard J, Turner M et al (2021) Africa’s evolving vegetable seed sector: status, policy options and lessons from Asia. Food Secur:1–13

Springmann M, Spajic L, Clark MA et al (2020) The healthiness and sustainability of national and global food based dietary guidelines: modelling study. BMJ 370

Stadlmayr B, Charrondiere UR, Eisenwagen S, Jamnadass R, Kehlenbeck K (2013) Nutrient composition of selected indigenous fruits from sub-Saharan Africa. J Sci Food Agric 93(11):2627–2636

Sunderland TC, Vasquez W (2020) Forest conservation, rights, and diets: untangling the issues. Front For Glob Change 3:29

Swinburn BA, Kraak VI, Allender S et al (2019) The global syndemic of obesity, undernutrition, and climate change: the Lancet Commission report. Lancet 393(10173):791–846

Thar C-M, Jackson R, Swinburn B, Mhurchu CN (2020) A review of the uses and reliability of food balance sheets in health research. Nutr Rev 78(12):989–1000

Thomson CA, Ravia J (2011) A systematic review of behavioral interventions to promote intake of fruit and vegetables. J Am Diet Assoc 111(10):1523–1535

Thow AM, Snowdon W, Labonté R et al (2015) Will the next generation of preferential trade and investment agreements undermine prevention of noncommunicable diseases? A prospective policy analysis of the Trans Pacific Partnership Agreement. Health Policy 119(1):88–96

Thow AM, Verma G, Soni D et al (2018) How can health, agriculture and economic policy actors work together to enhance the external food environment for fruit and vegetables? A qualitative policy analysis in India. Food Policy 77:143–151

Van den Bold M, Quisumbing AR, Gillespie S (2013) Women’s empowerment and nutrition: an evidence review, vol 1294. International Food Policy Research Institute

Vandevijvere S, Barquera S, Caceres G et al (2019) An 11-country study to benchmark the implementation of recommended nutrition policies by national governments using the Healthy Food Environment Policy Index, 2015–2018. Obes Rev 20:57–66

Vivero-Pol JL, Ferrando T, De Schutter O, Mattei U (2018) Routledge handbook of food as a commons. Routledge, London

Weinberger K, Lumpkin TA (2007) Diversification into horticulture and poverty reduction: a research agenda. World Dev 35(8):1464–1480

Wiebe K, Prager S (2021) Commentary on foresight and trade-off analysis for agriculture and food systems. Q Open 1(1):qoaa004

Willett W, Rockstrom J et al (2019) Food in the anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet 393(10170):447–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31788-4

Wohner B, Pauer E, Heinrich V, Tacker M (2019) Packaging-related food losses and waste: an overview of drivers and issues. Sustainability 11(1):264

World Health Organisation (2003) Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases. WHO technical report series 916

Yates J, Deeney M, Rolker HB, White H, Kalamatianou S, Kadiyala S (2021) A systematic scoping review of environmental, food security and health impacts of food system plastics. Nature Food 2(2):80–87

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Harris, J., de Steenhuijsen Piters, B., McMullin, S., Bajwa, B., de Jager, I., Brouwer, I.D. (2023). Fruits and Vegetables for Healthy Diets: Priorities for Food System Research and Action. In: von Braun, J., Afsana, K., Fresco, L.O., Hassan, M.H.A. (eds) Science and Innovations for Food Systems Transformation. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_6

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-15703-5_6

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-031-15702-8

Online ISBN: 978-3-031-15703-5

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)