Abstract

In this chapter, I analyze state entrepreneurship, as exercised through mission-oriented innovation policy: the mobilization of large pools of resources and capabilities to solve the pressing issues of our time. The state entrepreneur is not subject to real risk, often faces no market, and cannot be properly evaluated. It pays no price for being wrong and it struggles in assigning responsibility. Missions are motivated by a false dichotomy: that there is a difference in principle between fixing and creating markets. This premise is splitting hairs at best. Instead, what sets missions apart, other than sheer ambition, is a shift from bottom-up to top-down approaches to knowledge creation. Missions are most likely to achieve intended ends when reasonable people agree on the problem, what needs to be done, and when responsibility can be assigned. Even then, opportunity costs are ignored. The entrepreneurial state is currently pushing to solve those issues where it is likely to do the least good and the most harm: where we lack the knowledge of what to do, where accountability is unassigned, and where the failure-success axis cannot be meaningfully assessed. Successful mission policy further requires politics well beyond what democratic systems can achieve.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Calls for the state to act entrepreneurially are currently permeating innovation policy in large parts of the world. But what does it really mean to be an entrepreneur in a system of innovation, and further, for the state to act out that role? Those are, in a nutshell, the questions posed in this chapter. Before we turn to state entrepreneurship and its corollary, mission-oriented innovation policy, we need to grapple with the first question. What is an entrepreneur and why do we need to understand that function to assess innovation policy?

Entrepreneurs who assume risk by putting their money and reputation on the line provide us with new and better things, but they also play a different role. They constitute the glue in any well-performing system of innovation by probing the commercial viability of knowledge, broadly defined as know-how to fulfill desired ends. By prowling for commercially useful knowledge, they also spread it (Acs et al., 2009) and advertise its use across occupations, industries, and other settings. But the complexity, decentralized nature, and sheer range of all potential sources of knowledge and opportunities imply that economists have generally considered it impossible for the entrepreneurial function to be performed centrally, as argued by Hayek (1945).

The above statements represent known facts of the market economy and are hardly controversial. To anyone in the business of trying to improve a system of innovation, encouraging productive entrepreneurship should then seem like low-hanging fruit. We also know a substantial amount about how to promote productive entrepreneurship, at least in the sense that businesses respond to incentives. For instance, Baumol and Strom (2012) discuss how we can learn from historical institutional arrangements to prune our present institutions to make entrepreneurship more socially productive. Elert et al. (2019) convincingly argue that regulations of capital and labor markets, the taxation system, property rights, and entry and exit barriers all represent areas that are both important for productive entrepreneurship and actionable for makers of policy. In the Knowledge Spillover Theory of Entrepreneurship, Acs et al. (2009) similarly argue that regulations, administrative burdens, and market intervention create friction as knowledge diffuses in the economy. By focusing on supporting the production of knowledge, proper infrastructure in the broad sense, and maintaining and sometimes carefully shaping institutions, politicians can fuel and lubricate what Baumol (2002) dubbed the innovation machine. Broadly speaking, this is what successful societies have done in the past (see e.g., Landes et al., 2010).

But when governments set out to improve our present innovation systems, they decreasingly do what we know how to do and what we have successfully done in the past. Today, they direct their efforts and our resources toward what we do not know how to do, in attempts to solve what politicians and civil servants consider the big issues of our time. This is all in response to challenges identified by the state and formulated as missions. The call is for the state to be outright entrepreneurial in the generation and application of knowledge to different ends, in steering the direction of private sector innovation, and in mobilizing the entire breadth of the state apparatus to do so. That is, a first difference to note between entrepreneurship and state entrepreneurship is that they depart from opposite ends of the scale in terms of how they identify an opportunity (or threat). While entrepreneurs work at the intersection of available capabilities and opportunities, the state can afford to ignore either, or both.

At the heart of this matter lies the current push for the state to go beyond market failures. More specifically, some academics and many policymakers now call “for public policy to actively create and shape markets, not only to fix them” (Mazzucato & Penna, 2015, p. 4). These calls are generally accompanied by anecdotes of how this practice has presumably worked in the past, rather than by clear guidance for how it can work in the future, or how missions can be evaluated. Hekkert et al. (2020, p. 77) note that while “‘missions’ is the new buzzword in policy departments, both analysts and policy makers are struggling in their attempts to design and implement [mission-oriented innovation policy].”

The call, I argue, is for the state to work on issues better described as subject to genuine market failure: specific problems or opportunities of great public interest, but with an often unclear end goal to be arrived at by often unknown means. The notion that these issues are not characterized by market failure is only true by an overly strict definition of that term. Because why are they of great public interest? Because they are subject to large positive or negative externalities, or other market failures, making it unattractive for the market to engage. Bringing about a sector or market that is not there because of market failure is fixing it. Before we had a national defense, creating it may not have seemed like fixing a market, but it was ultimately about coordinating buyers and sellers of a service who could not come together because of its public good like properties, i.e., market failure. The perceived dichotomy between the new and the old is splitting hairs, and the raison d’être for mission-oriented innovation policy is still market failure in this broader sense.

The call for state entrepreneurship is for the state to be not just entrepreneurial, but rather something like the entrepreneur: what Schumpeter (1961) identified as the force that moves the economy toward new equilibria. The difference is that the forces bringing those equilibria about are determined from the top down rather than from the bottom up. The result is a situation in which state entrepreneurship crowds out market-driven entrepreneurship. Indeed, a central tenet of mission-oriented policy is tilting the playing field away from unwanted solutions (Mazzucato, 2016). This process then obviously involves picking winners—an activity for which many of us are not convinced of the state’s expertise.

Researchers who push this narrative do argue that the state must be brave in these endeavors and indeed willing to fail. The problem is that the risk component inherent in the definition of entrepreneurship (Shane & Venkataraman, 2000) is lacking in state entrepreneurship. It is simply difficult to draw the line for what constitutes failure. Failure takes place in two main ways: we can succeed at doing the wrong thing, or we can fail at doing the right thing. The market is a mechanism that distinguishes failure from success in brutal fashion, regardless of the source of the failure. Whether entrepreneurs are unsuccessful at valued ends or successful at unvalued ends does not matter. Whether an entrepreneur produces bad ice cream and falls to competition from other ice cream firms or produces the best typewriters in the world and falls to competitive pressures from the computer industry matters little for the result. The government would need two mechanisms: one for each source of error. When the state fails at the right thing, the main risk is crowding out, in the ordinary sense: firms and technologies that would have better solved the problem are outcompeted. But the biggest long-term threat is that the state succeeds at doing the wrong thing and locks us into a suboptimal equilibrium by tilting the playing field: It crowds out alternative solutions and means altogether. No known method of evaluation could deal with these problems, because the biggest risk is wrapped in a counterfactual.

The two overarching questions are first, how do we ensure that the state pays a price for being wrong? And second, when is that price high enough for us to know it is time to cut our losses? The fact that the state can produce policy failure by being wrong about means or ends severely complicates this question. In addition, even when and if the state’s venture appears highly successful, we simply do not know the counterfactuals. How large is the graveyard of ideas that were never put into practice because the state tilted the playing field the other way? The answer is not merely unknown but unknowable. It is, in Bastiat’s (1850) words, not seen.

Many specific problems—often the most obvious ones—that involve genuine market failure are also global, and it is far from obvious that individual governments should be involved in trying to solve them. For most states trying to be entrepreneurial, there exists a small economy paradox: when the identified issues are significant and evident enough, the small state lacks critical mass. But in the opposite situation, with problems of sufficiently narrow scope, the state itself almost always lacks the expertise both in identifying and solving the problems. When it demonstrably possesses that expertise, it is likely to meet little opposition. The entrepreneurial state narrative has grown out of a big state context, mostly with examples from the United States, where the state has access to resources and know-how that other states simply do not possess. The idea that nation-states a tiny fraction of the size of the United States could in any way be employed in solving similar problems is like asking your local pizzeria to produce a gourmet dinner for 500 guests. It is possible that smaller states have enough research or business excellence to solve some component of a larger problem, but then they are probably better off employing those smart specialization strategies that already exist and that we know much more about (see e.g., the overview in McCann & Ortega-Argilés, 2015). That is, proponents of entrepreneurial states and their missions regularly ignore several facets of the market economy but also of political reality.

The chapter is outlined as follows. Section two selectively reviews growth theory to put our innovation efforts in a larger perspective. It also moves on to draw some conclusions for state policy based on theoretical developments in economics. Section three takes a more detailed look at the market failure vs. market creation justification for state entrepreneurship. Section four asks to what extent anecdotes from large countries can be extrapolated to smaller ones and ponders the possibility of international cooperation. Section five concludes.

2 Innovation and Entrepreneurship: A Knowledge-Based View

The canonical growth models, i.e., the exogenous growth framework (Solow, 1956) and its endogenous counterpart (Lucas, 1988; Romer, 1986), have guided our thinking around economic growth in academia and policy circles alike. These models clearly contain something deeply important about economic growth and prosperity. By learning how to do things more efficiently, and by coming up with new things to do, we can have products and services of higher quantity and quality, at a cheaper price than before, and entirely new products and services. In short, growth models tell us that we need to innovate to grow.

The point of departure for endogenous growth models was that growth built on increasing, not decreasing, returns to ideas. The more we learned, the more we managed to combine old and new ideas in a cumulative growth process. In turn, these models have often been criticized for not explicitly associating knowledge-creation or growth with a mechanism, and sometimes for ignoring the role of innovation. Rosenberg (1982, p. 4) and Baumol (2002, p. 9) both refer back to an old English saying and comment that thinking of technical progress without innovation “is to play Hamlet without the prince.” Rosenberg also pointed out that researchers generally, and Schumpeter in particular, had been more interested in the way innovations reshaped society, rather than in the actual sources of innovation. These are certainly objections that a serious treatment of systems of innovation will have to take seriously.

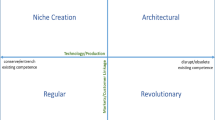

Policy to enhance growth through innovation can come in two broad categories. First, it can accumulate and help the spread of knowledge, i.e., it can support our brains and give us infrastructure to spread what we know and verify that our know-how is indeed commercially viable. This first category contains a crucial, and up until a couple of decades ago understudied, component: entrepreneurship. Baumol (2002, p. 10) pointed out that even though medieval China and ancient Rome did produce a solid number of inventions, a “systematic innovation mechanism” was lacking. We may loosely refer to approaches aimed at these functions as bottom-up policy because their main objective is to exploit, nourish, and support the grassroots in the quest for eventual gains at a more global level.

Second, and clearly, the state can also identify what specific knowledge we need, bring about innovations itself, or bring about growth through state-owned businesses and other bodies. This second category of solutions has always been appealing to politicians and representatives of the state more widely, which is no wonder. This category represents solutions in which the state is brave, heroic in effort, and indeed entrepreneurial. We may, equally loosely, call this top-down policy.

Many top-down policies misunderstand a crucial aspect of knowledge: it is not a public good, but in fact mostly a club good. Rather than non-rival and non-excludable it is non-rival and partially excludable, and it is particularly excludable in the early stages of development. Entrepreneurs do not merely spread knowledge; they take club goods and push them closer to being public goods through the innovation process. When Henry Ford searched for profit by mass-producing cars, he also demonstrated his knowledge to a much wider audience. Without engaging the best entrepreneurs, any innovation policy will be inefficient. That is to say: any efficient top-down approach must be linked to bottom-up forces and find ways of prioritizing some bottom-up actors over others.

Baumol (2002) argues that the market economy is in effect an innovation machine. By having no choice but to arms race each other, firms are forced to find new niches, improve existing products, and find new markets. That is, innovation becomes the primary weapon in each individual firm’s battle for survival. If the right knowledge is out there, and if the framework conditions are right, an entrepreneur will find it and turn it into something valuable. If that person is successful, more firms will follow suit and further refine the innovation, and of course introduce competing technologies.

A new wave of thinking about growth has come to incorporate entrepreneurship more explicitly. Acs et al. (2009) remark that part of “the endogenous” in endogenous growth theory is the creation of technological opportunities, driven by conscious investments in knowledge. In their model, entrepreneurs exploit knowledge that leaks out from incumbent firms and unto the rest of the economy. An entrepreneur is something like a dynamic conduit for finding, probing, and ultimately spreading knowledge. Acs et al. (2009) show that greater regulation, administrative burdens, and market intervention will reduce the knowledge available to us.

To be sure, this role of private enterprise does not preclude a substantial role for the state; it is not a point of ideology. But the knowledge-carrying function of entrepreneurship implies that intervening with the process comes at a risk. It is certainly possible that by steering firms into more productive, or more socially desirable activities, the state may improve upon things. This much seems to have been known by almost every ruler since the invention of enterprise (see for instance, the exposé in Landes et al., 2010). But this almost self-evidently correct claim—the could—does not in and of itself lead to the conclusion that the state should be actively involved in these things, because we are not living in a first-best world. This would require the state to have some method for picking the right paths among many possible ones.

A key thing to understand is that private sector entrepreneurship has not been invented; it has evolved (Winter & Nelson, 1982). In a cocktail of local and regional institutions, available human capital, and input from markets, small and large firms have butted heads. What remains is, with simplification, either deeply battle-tested, currently challenging the status quo, or funded by investors who are too patient. Actors in social systems can indeed copy behaviors of others and entrepreneurship is no exception (Andersson & Larsson, 2016), so it is by no means impossible for top-down entrepreneurs to do well by learning from the past and the present in similar ways. In fact, the best-case scenario—when one entrepreneurial state figures something out that really works, other states copy it—can work under the right circumstances. But key for the state is to know two things: first, it must challenge the status quo in the right way. Even when the state appears to have been highly successful, it is possible that the results are disastrous if it has crowded out better solutions to the problem at hand. Second, it needs to be able to tell when it has turned into an overly patient investor that should cut its losses.

There is a key difference between the state as innovator and the free-market system the way Baumol describes it: it is not clear how the state can bear any costs of being wrong (in part because it is unlikely to know when it is wrong, as noted above). The arms race that drove firms to innovate to stay ahead of the competition is not there for the state, except for in a few exceptional cases, such as literal arms races. The one real cost that the state does bear for being wrong is possible embarrassment a long time into the future, if at that point it is obvious that it backed the wrong horse. That is, the state does not carry much risk, mostly none at all, and as such it cannot act entrepreneurially the way we normally define the term (see e.g. Shane & Venkataraman, 2000, p. 222). It simply is not its area of expertise, just as running the police force is no area for private businesses. That the incentives are skewed the wrong way is not evidence that the state cannot mimic entrepreneurial behavior, or for that matter, that competing private enterprises could not run a working police force. But these are extraordinary claims, and we should require extraordinarily good arguments from those who want to go down those paths.

3 Market Failure and the Entrepreneurial State

A central claim in motivating the wider role for the state is that it must do much more than fixing broken markets. The state should create markets. Mazzucato (2016) juxtaposes this view against what she calls “market failure theory.” Mazzucato (2016, p. 143) claims that “[market failure theory] justifies public intervention in the economy only if it is geared toward fixing situations in which markets fail to efficiently allocate resources (Arrow, 1951)” (reference in original). It remains unclear who the proponents of this theory really are and what their influence is. Mazzucato’s reference is to Kenneth Arrow’s famous extension of the welfare theorems of economics. It is doubtless true that it can be inferred from the referenced article that the presence of market failures can motivate government involvement. Arrow (1962) made this point eloquently, where he showed how invention suffered from all classical sources of market failure and note that invention in Arrow’s vocabulary referred to the production of knowledge in a broad sense. Does this in any way show that the only reason for governments to intervene is market failure? No, it does not; it simply means that investment in knowledge suffers from a particularly difficult form of uncertainty. Arrow himself most certainly did not think that any such ideological view followed upon his theory. He was clear on the fact that efficiency was not necessarily the main value in an economic system, and he often sketched out a nuanced role for the state, as his magazine article A Cautious Case for Socialism (1978) makes abundantly clear. He did not pick the title of the article, but it shows how his thinking, even at the time of working on welfare theorems, was very clearly never that market failure was the ultimate or only motivation for government involvement. Few of the classical economists held that view. Given a certain framework of law and order and certain necessary governmental services, they seem to have conceived that the object of economic activity was best attained by a system of spontaneous cooperation (Robbins, 1978). This meant mostly that we should not intervene in the way we produce or consume, given existing means-ends. What an economist should think of the development of new means-ends is simply not clear from theory alone.

What can definitely be said is that a dominant innovation policy for a time was promoting R&D with the motivation that market failures caused societies to underinvest (Schot & Steinmueller, 2018). A narrower statement of the market failure theory would propose that “government support of R&D should only be justified on grounds of ‘market failure’” (Nelson, 2011 p. 687). This position certainly does have adherents in the economics profession, and it does limit the scope of policy. Nelson continues by noting that while this position is (Ibid) “not necessarily a high obstacle to the development of active policy in an area, the market-failure orientation starts by asking what the market will not do, rather than what kinds of fruitful roles active policy can play.” He notes that the latter view could probably often be more fruitful when asking what we can do to improve innovation systems.

At the center of this issue is the question of what it means to create a market and what it means for markets to fail. This discussion resembles the issue of whether the proverbial falling tree makes a sound or not. Akerlof’s (1970) point in The Market for Lemons was not simply that information asymmetries would make the market function less smoothly. A central argument was that if the information asymmetries are severe enough, there would be no market! But surely, the state is not creating a market by mandating that used car salesmen offer warranties.

Judging by the wide range of innovation policies that exist in all developed nations, as well as those innovation funds for risky ventures and ideas that are now ubiquitous, the fix market failures only paradigm is not too influential at present. Few economists seem to think that the most cited missions—putting a man on the moon or helping plant the seeds for the internet—were in any way bad ideas. It is easy to imagine that part of the reason is that these accomplishments were associated with enormous positive externalities. That is, the investor in them could not keep the gains private. That is, at least to some extent, these successes can be understood through a theory of market failure perfectly consistent with Arrow (1962). There is, in that sense, no real difference between what proponents of the entrepreneurial state or mission-led innovation propose as the old and the new.

It is of course a fact that economists and others subscribe to a market failure way of thinking, but that does not mean that the only reason for government involvement is market failure in the Pigouvian sense in which a tax or a subsidy bridges the difference between private and social costs (and most governments seem to prefer regulation and government ownership, anyway). In many circumstances—I shall argue which below—even most classically schooled economists are probably prepared to go far beyond Pigouvian fixing and into something that we may tentatively refer to as genuine market failure: problems or intriguing opportunities that most can agree on but where means and often ends are obscured.

Historically, with things that have clear outcomes, measurability, and in which buyer–seller incentives are clear enough, economists seem to have been rather supportive of large-scale state innovation efforts, even in the absence of narrowly defined market failures. I would argue that the recurring example of putting a man on the moon is precisely the kind of thing that the classical economists could probably get behind: it is an intriguing feat; it was generally a popular idea among the public; it was likely to lead to some real insights and technological spillovers; the process would indirectly let us evaluate a large number of theories, and given some time it would be possible to determine whether it was time to pull the plug. Crucially, As Nelson (2011, p. 688) pointed out, the same entity was in fact “the intended and eager user of the technology developed, as well as the funder of the R&D.” Accountability and incentives were in place. The state investing in ARPANET would seem to follow a similar logic. In addition, it was infrastructure, which most consider at least largely a state activity that we generally believe comes with large spillovers if done right. Investment in high-risk infrastructure is of course nothing new and debates on cost-benefit analysis, accessibility, and spillover effects, as well as many other considerations, typically precede its construction.

In fact, the technological advances (the internet, biotech, the IT revolution, etc.) that act as canonical examples of good mission-oriented innovation also come with enormous positive externalities, have completely changed the way we think of information asymmetries, or relate to market failures in other ways. What really constitutes fixing markets that do exist on one hand and researching technologies that can fix markets that do not yet exist on the other can hardly be properly distinguished.

So, what really sets the new and old innovation strategies apart? The main difference—other than sheer size and risk of the endeavors—is a sizeable shift in favor of bottom-up, relative to top-down approaches.

3.1 Bottom-Up, Top-Down, and the Role of the (Entrepreneurial) State

For the purposes of our discussion here, by bottom-up approach, I will refer to processes in which the key decisions are taken by those with knowledge of time and place in Hayek’s (1945) analysis. By top down, I will mean that decisions are taken further up in a hierarchy, by someone who by construction is unable to overview all significant consequences of the actions taken. Bottom up is not always better and the context dictates what works, how, and when. Sowell (1980) argued that in the Soviet Union, top-down production plans worked relatively better in heavy manufacturing, whereas they almost always failed miserably in agriculture, where knowledge of time and place were keys to producing output.

The entrepreneurial state narrative represents a combination of top-down and bottom-up approaches. The call is for states to create markets, radically change the direction of research and development, and then let bottom-up forces work their magic. The example par excellence is the internet, for which radical public sector (defense) research seeded a development that was combined with exponentially increasing entrepreneurial effort to commercialize the new technology and extend it to more areas.

A mission needs to be backed by considerable central power from the very top. The leaders of a large mission will need to subsidize, regulate, and continuously find new top-down paths if the old ones are not working. Each path chosen will eliminate alternative paths, including those that would have followed on those alternative paths, and so on. One reason why economists and proponents of theories of market failure tend to support R&D subsidies is that such a policy works from the bottom up: It does not (at least not necessarily) tell firms what to do or how to do it. When the state is the entrepreneur, grassroot entrepreneurs are not as free to work, and ultimately to spread knowledge, because they are no longer as free to decide the direction of their efforts.

It follows that a main problem with top-down policies is that this category of activity crowds out bottom-up solutions. Crowding out can happen either through higher taxes, more regulations, or direct competition. It can also happen since top-down policies by construction alter the profitability of firms in different sectors, as well as of firms that employ unequally preferred means toward similar ends. Even if you are the most innovative manufacturer of a product, you will face problems if the state chooses to back a competing technology. Even if you develop the best technology to produce renewable energy, the state may already have supported a competing technology and pushed it across the Valley of Death, to the point at which it is just too cheap relative to your own.

What then seems to be the key characteristic of the entrepreneurial state narrative, other than sheer ambition, is that it moves more responsibilities over to the state in terms of picking the direction of innovative activity. What is not currently discussed very much is exactly what to do if a mission, say, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by some number, appears unfulfilled. Exactly which tools should the state have at its disposal to make a mission work, particularly if it appears to be failing? Should state bureaucrats be able to close firms that use carbon-emitting technologies? Should we be able to invade countries that counteract our missions? These are extreme cases in point, indeed, but not really knowing when to stop is an inherent problem with top-down policy. So are slippery regulation slopes; to make past efforts work, we need just one more tariff, one more regulation, or one last big-push subsidy. These questions raise a related problem: We seem to have absolutely no tools for evaluating these kinds of policy bundles, and in particular their effects on crowding out alternative technologies.

3.2 The Evaluation of a Mission

That mission-oriented innovation policy must be evaluated is uncontroversial. Nelson (2011, p. 684) noted that “one cannot learn from experiments if one does not have ability to identify, control, and replicate effective practice.” At present, there does not appear to exist a solution to this problem.

One source of several problems with state entrepreneurship is that a state departs from issues that it thinks need solving, whereas entrepreneurs in the innovation machine generally depart from issues they think they can solve. The former issues are subject to substantially more uncertainty. Most entrepreneurs are ultimately forced to be realistic, at least in terms of large investments. When they have attempted to solve a problem for too long, they run out of investors. When they fail at solving actual problems, or when they succeed at solving immaterial problems, they are broken by markets.

With state entrepreneurship, there are no such mechanisms. Taxpayers are not investors because they do not have equity. They do not know what is going on and even if they did, collective action problems would almost invariably stop them from showing up outside the board room. To the extent that there is a market, and often there will not be, a loss does not really mean anything if the politicians choose to remain committed to the enterprise. In democratic states, state entrepreneurship is venture without meaningful risk.

These issues clearly call for other mechanisms to evaluate the progress of state entrepreneurship and its missions. Mazzucato (2016, p. 141) calls for missions to be “concrete enough to translate into specific problems to solve, so that progress toward the mission can be evaluated on a continual basis.” It is not controversial to say that such evaluation methods are still missing, and that is even if we disregard opportunity cost.

Is there any reason to be hopeful that credible evaluation methods may emerge? To begin with, it is of course correct that missions must at the very least be concrete; they cannot simply consist of making the world better. But even in the case of something concrete, like cutting carbon emissions by 50% in ten years, a myriad of problems remains to be dealt with. Even if this is a national target, for an accurate evaluation, we would need to know the direct effect of the policy, the indirect effects of the policy, including opportunity costs imposed on seemingly unrelated sectors, and whether the policy was achieved or not achieved through acceptable means. The latter point is important because the state’s powers are so far-reaching. Simply regulating all carbon-heavy firms out of business would not seem like success to most people, although it could certainly achieve the goal.

Taken together, these points can be summarized to mean that it is not enough for the goal to be concrete and measurable. The indirect outcomes must be clear and quantifiable as well. And even when they are, there can be no one and nothing else to blame for failure. In the end, state entrepreneurs are often not accountable to anyone, whereas the Apollo and Manhattan projects, for example, were notable exceptions since the goals were perfectly defined and there were formidable competitors. Even when someone is accountable, one of the main tenets in the mission-oriented innovation literature is that we should be prepared for the state to fail in these high-risk and large-scale endeavors. Indeed, the state should experiment, and we should often expect failure, although to what extent is not clear. It seems as an entity, the entrepreneurial state cannot fail. Whatever we are to call this process, it is not entrepreneurship.

4 External Validity and Scalability: The Problem with Arguing from Anecdote

I have argued that we should not expect the state to be able to act entrepreneurially, at least not in terms of the currently accepted use of the word. But one argument remains. Most would agree that some problems are clearly so large and so urgent that the market cannot properly address them, and perhaps whoever is addressing them may need both the resources and the capacity to make rules and regulations as well. What does that tell us in practice?

As noted, an entrepreneurial state departs from issues it thinks should be solved, whereas the innovation machine departs from issues that its firms are likely to be able to solve. Sometimes we cannot direct the machine’s effort to the most important issues of our time. A common problem in a high-risk venture is embodied in the question, are we engaged with a problem that we can solve? Ask any producer of pharmaceuticals. One obvious problem that has flown under the radar in the debate about the entrepreneurial state and its ambitions is the seemingly innocuous fact that there is not one state out there. Arguing over what a state should do is like arguing what a business should do, without considering whether the business is a multinational firm with thousands of scientists or whether it is your local ice cream vendor. Sweden is currently less than one-thirtieth of the size of the United States. Sweden could never have mobilized a defense initiative to put a man on the moon, because it lacks the scale. If you depart from what needs to be done—as the state is prone to—rather than from what we can do, this fact is likely to be ignored.

So, is the international arena the solution? Perhaps, but the current track record of cooperation over global warming and resistant bacteria are not too encouraging. Politicians are also increasingly wary of centralizing policy because it turns out that people who are not centrally located tend dislike centralization and cast votes for parties that align with their views (Rodríguez-Pose, 2018).

By necessity, resources pooled in the international arena would probably need to go to the most efficient environments to make the most good. As noted above, cutting-edge knowledge is to a large extent a club good. Even absent patents and secrecy, advanced knowledge is tacit, and as Glaeser (2011) has remarked, it flows easier across hallways than oceans. Researchers in the regional sciences have shown that promoting research excellence in the central agglomerations is most efficient (Varga, 2015). This peculiarity clearly favors building those knowledge-creating environments that are already strong, and over time, to the extent they favor the best proposals to deal with our missions, funds will naturally favor already-strong environments. But taking resources locally and concentrating them in central locations is ever-less popular politics, even when it is nominally the right policy. There is perhaps a way that we could get over any democratic challenges. But the international arena would also need far-reaching regulatory power at the local level. If missions are to be effective politics, many issues remain to be answered in terms of how they can operate within, as well as across, democratic systems.

Within nations, efficient missions will need to be wrapped in an unpopular anti-cohesion agenda. Across nations, we face a macrocosm of the same problem. Our national-political innovation systems are not built for this development, just as our political systems are not. In fact, the only man-made entities that act efficiently across borders are armed forces and multinational firms.

5 Concluding Remarks: Can Missions Work?

This chapter has analyzed the innovation machines within our societies, making a case that the entrepreneur is, next to human capital, its most integral part. I have also argued that those market forces that spur and fetter entrepreneurs do not translate in any simple way to the realities of the state. A firm that is hijacked by a bad idea suffers financially. A state that is hijacked by a bad idea is unlikely to suffer by any parameters it cares about. It might even find parameters by which it appears successful and tout its success.

The most recent call for the state to be entrepreneurial involves so-called mission-oriented innovation policies: the mobilization of great resources across many sectors to solve a great problem or act on an opportunity. Missions suffer from three overarching weaknesses. First, we do not know how to pick them or operationalize them. Second, we do not know how to evaluate their successes and failures, and it is likely that we will never be able to do so in a satisfactory way, since the opportunity costs are incredibly complex. Third, it is difficult to make an actual flesh-and-blood person accountable, which greatly increases the risk that an unproductive, or even destructive, project is initiated, as well as supported past its due date.

Sometimes a simple answer is not simplistic. In his famous 1977 book, The Moon and the Ghetto, Richard R. Nelson asked how it came to be that humankind managed to put a man on the moon but could not help ghetto kids read. It is of course a hopeful proposition that resources and political willpower are the missing pieces, as embodied in the call for missions. But when Nelson reflected back on his book almost 35 years later (Nelson, 2011, p. 685), he recalled that a central argument of the book, and something he considered still central to things we could not do, was “not so much political, as a consequence of the fact that, given existing knowledge, there were no clear paths to a solution.”

With problems for which what to do is reasonably straightforward, it is obvious who the experts are, we can draw on already well-developed knowledge in science and private enterprises, and there is currently a lack of critical mass, missions may work in theory. The question is how many problems of significant importance fit those criteria. We must also figure out how these things interact with the institutional-technological issues of our time. Hammurabi could not have flown to the moon, but he is likely to have been able to fix a few issues with readability in ghettos if he had so intended. Today, things like fly a rocket to land on the moon clearly qualify for the list of achievable missions, as do things like building the world’s fastest car or the world’s best chess computer. Find an accountable head, hire the best minds, and pour endless resources into them. The problem of opportunity cost would remain, but the mission’s goals could probably be reached.

It is possible that putting enormous amounts of resources into staying ahead of resistant bacteria would qualify as well, given that the taxpayers involved are willing to pay for everybody else’s spillovers. Some vaccine research and roll-out programs may also be candidates. But then again, would that not be best performed through enormous R&D subsidies or innovation prizes, rather than through missions?

Sadly, dealing with global warming (and many other issues of our time) is not on the list of problems that are likely solvable through missions: We just do not know what to do about it, at least not in a way that enough people find acceptable. Contrary to the Apollo or Manhattan projects, it is unlikely that one technological solution will take us past the global warming scare (Mowery et al., 2010), exponentially increasing the complexity of the problem and likewise reducing the likelihood that a mission can solve it. Alas, those are the kind of missions that we are steering against. Indeed, not really knowing what to do is perhaps what ultimately separates fixing markets from creating markets. Proponents of entrepreneurial states and their missions are trying to convince us to apply top-down approaches to issues for which the knowledge required is too complex and too incomplete for top-down approaches to work. If we allow our states to take on such issues, they are likely to fail in more ways than one. Many politicians and civil servants will likely have a favorable view of their ability to do the impossible. The rest of us must keep our heads cool.

References

Acs, Z. J., Braunerhjelm, P., Audretsch, D. B., & Carlsson, B. (2009). The knowledge spillover theory of entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 32(1), 15–30.

Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for "lemons": Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500.

Andersson, M., & Larsson, J. P. (2016). Local entrepreneurship clusters in cities. Journal of Economic Geography, 16(1), 39–66.

Arrow, K. J. (1951). An extension of the basic theorems of classical welfare economics. Paper presented at the Second Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability,.

Arrow, K. (1978). A cautious case for socialism. Dissent (Fall issue), 472–480.

Arrow, K. J. (1962). Economic welfare and the allocation of resources for invention. In R. R. Nelson (Ed.), The rate and direction of inventive activity. Princeton University Press.

Bastiat, F. (1850). Selected essays on political economy (Ch 1. What is seen and what is not seen). Foundation for Economic Education.

Baumol, W. J. (2002). The free-market innovation machine: Analyzing the growth miracle of capitalism. Princeton University Press.

Baumol, W. J., & Strom, R. J. (2012). “Useful knowledge” of entrepreneurship: Some implications of the history. In D. S. Landes, J. Mokyr, & W. J. Baumol (Eds.), The invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from ancient Mesopotamia to modern times. Princeton University Press.

Elert, N., Henrekson, M., & Sanders, M. (2019). The entrepreneurial society: A reform strategy for the European Union. Springer Open.

Glaeser, E. L. (2011). Triumph of the City–how our greatest invention makes us richer, smarter, greener, healthier and happier. The Penguin Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). The use of knowledge in society. The American Economic Review, 35(4), 519–530.

Hekkert, M. P., Janssen, M. J., Wesseling, J. H., & Negro, S. O. (2020). Mission-oriented innovation systems. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, 34, 76–79.

Landes, D. S., Mokyr, J., & Baumol, W. J. (2010). The invention of Enterprise: Entrepreneurship from ancient Mesopotamia to modern times. Princeton University Press.

Lucas, R. E. (1988). On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(1), 3–42.

Mazzucato, M. (2016). From market fixing to market-creating: A new framework for innovation policy. Industry and Innovation, 23(2), 140–156.

Mazzucato, M., & Penna, C. C. R. (2015). Introduction: Mission-oriented finance for innovation. In M. Mazzucato & C. C. R. Penna (Eds.), Mission-oriented finance for innovation (pp. 1–10). Rowman & Littlefield.

McCann, P., & Ortega-Argilés, R. (2015). Smart specialization, regional growth and applications to European Union cohesion policy. Regional Studies, 49(8), 1291–1302.

Mowery, D. C., Nelson, R. R., & Martin, B. R. (2010). Technology policy and global warming: Why new policy models are needed (or why putting new wine in old bottles won’t work). Research Policy, 39(8), 1011–1023.

Nelson, R. (1977). The moon and the ghetto: An essay on policy analysis. W W Norton.

Nelson, R. (2011). The moon and the ghetto revisited. Science and Public Policy, 38(9), 681–690.

Robbins, L. (1978). The theory of economic policy: In English classical political economy (2nd ed.). The Macmillan Press.

Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209.

Romer, P. M. (1986). Increasing returns and long-run growth. The Journal of Political Economy, 94(5), 1002–1037.

Rosenberg, N. (1982). Inside the black box: Technology and economics. Cambridge University Press.

Schot, J., & Steinmueller, W. E. (2018). Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy, 47(9), 1554–1567.

Schumpeter, J. (1961). The theory of economic development. Oxford University Press.

Shane, S., & Venkataraman, S. (2000). The promise of entrepreneurship as a field of research. The Academy of Management Review, 25(1), 217–226.

Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94.

Sowell, T. (1980). Knowledge and decisions. Basic Books.

Varga, A. (2015). Place-based, spatially blind, or both? Challenges in estimating the impacts of modern development policies: The case of the GMR policy impact modeling approach. International Regional Science Review, 40(1), 12–37.

Winter, S. G., & Nelson, R. R. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign’s Academy for Entrepreneurial Leadership Historical Research Reference in Entrepreneurship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Larsson, J.P. (2022). Innovation Without Entrepreneurship: The Pipe Dream of Mission-Oriented Innovation Policy. In: Wennberg, K., Sandström, C. (eds) Questioning the Entrepreneurial State. International Studies in Entrepreneurship, vol 53. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-94273-1_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-94272-4

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-94273-1

eBook Packages: Business and ManagementBusiness and Management (R0)