Abstract

This chapter presents the research design of the ProSEPS comparative project on advisory roles of political scientists. In order to operationalize the theoretical concepts on policy advice and policy advisory roles as introduced in Chap. 2, the project uses the questions included in a large scale comparative survey to European political scientists conducted under the ProSEPS COST Action in 2018 to assess whether and how they engage in advisory activities. Chap. 3 first presents details about the content, scope, and implementation of this survey. Second, it describes how survey questions are used to operationalize the four basic types of advisory roles analyzed in the book (pure academic, expert, opinionating scholar, and public intellectual). Finally, the chapter also presents some details about the sample of 12 countries analyzed in the book, including on gender, job status, sub-disciplinary orientation, and external positions of political scientists.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Given the mostly unknown status of the professional viewpoints and behavioral repertoire of political scientists outside their university home basis, the best approach to acquire a better understanding is a systematic empirical analysis across countries. In this chapter we present the structure and questions included in a large scale survey to assess whether, how and why political scientists take up advisory roles. Empirically measuring attitudes and behavior with regard to the different possible roles of academics in their political and social environment not only requires good coverage of the types of activities and push or pull factors related to them, but also that relevant and valid indicators are used. Our strategy of data collection and analysis in this comparative project builds directly on the conceptualization of policy advisory systems and the boundary work roles performed by academic political scientists.

Linking theoretical elegance and empirical relevance is crucial for coming to grips with a reality we want to assess and for drawing lessons about the theoretical lens used. The focus taken in this book is on how political scientists as a category of academics move in the policy advisory system. This is an empirical enterprise not undertaken thus far within political science as a discipline. In other fields such as economics and law, engagement of academics has received some attention, but by and large, the boundary work between scholars based at universities and policy makers is still a mostly unknown territory in comparative research. The typology of advisory roles developed here may apply to other scientific fields, not only in the social sciences, but also in other disciplines for which one central question is tabled: do academics engage in policy advisory work? In this chapter, we turn the simple model of advisory roles into measurement in order to enable empirical investigation of the occurrence, reasons, and various forms and content of advising.

In Sect. 3.2 we first present our survey design and the underlying purposes developed within the broader COST Action on the Professionalization and Social Impact of European Political Science (ProSEPS) (COST Action CA15207). This project including 39 countries has organized the most complete and ambitious survey ever realized among political scientists in Europe, dealing with viewpoints on and experiences with advisory roles, media outreach (Real Dato & Verzichelli, 2021), institutionalization of the discipline of political science (Ilonszki & Roux, 2021), and internationalization of scholars. By Europe, we mean countries of the European Union and other countries such as Norwayand Turkey. The dimensions of advising and advisory roles are covered by survey questions presented in this part of the chapter.

Next, we present our indicators in Sect. 3.3. How can we, when observing the daily reality of academic political scientists at work, distinguish pure academicsfromexperts, opinionating scholars andpublic intellectuals? Whatmakes a typical expert or a public intellectual, what thresholds must be used for classifying scholars in each of these roles? In Sect. 3.4 of this chapter we move on to presenting some basic elements of the response to the survey, such as the size of the scholarly community in the countries included, the level of participation in the survey, and implications of response for findings and conclusions to be drawn. Section 3.5 presents more features of the sample of respondents that form the basis of the twelve country chapters in this book and the comparative analysis following after it. These general features thus set the stage for part II of this book with the in-depth analysis of twelve countries, from Albania to the United Kingdom. Section 3.6 concludes the chapter.

2 A Large Scale Survey for Comparable Data Across Countries

While political scientists use surveys extensively in empirical research, it is rarer to see this method applied for mapping of and reflecting on the scholarly community itself. Political science is no exception here—enquiry into state of the art of the own discipline is no daily business in most academic fields. In fact, in political science, research on the state of the discipline and the community of scholars does happen. A prominent example is the cross-national survey The World of Political Science (WPS) organized by Professor Pippa Norris and a team of leading scholars on the opinions on and experiences with career development of political scientists. This survey conducted in 2019 in conjunction with the European Consortium for Political Research (ECPR) and the International Political Science Association (IPSA) provides an up to date mapping of the scholarly community, focusing on academic career paths and perspectives. The WPS survey addresses activities and underlying motivations of political scientists, but not engagement outside the university, such as advisory work. The COST Action on the Professionalization and Social Impact of European Political Science was developed synchronously to the WPS, but with a different focus. It deals with the institutionalization and internationalization of the discipline, but also with advisory work and media exposure. This pan-European survey is the most complete enquiry into external visibility and activity of political scientists employed at universities in European countries ever organized (ProSEPS 2019). The survey questions central to this book deal with the content of advice, frequencyofadvice, recipients of advice at different levels of government, the formality or informality of advice, channels and modes of advice, aswell as with the normative views on engagements of political scientists and intrinsic and extrinsic incentives for policy advice, such as the professional world view, career perspective and incentives or disincentives for engagement.

The design of the survey took place at several meetings between February and December 2017 (La Valetta, January 2017; Siena, March 2017; Leuven and Florence, September 2017; Brussels, December 2017). During 2017, the country experts collected the respective lists of political scientists who would constitute the population of the survey. The general criteria used to select the population were individuals working at academic research institutions (universities, research centers), who (a) held a PhD in political science or were affiliated to formal organizational units within universities (departments, areas, etc.) where the main specialization was political science or a related field (public administration, international relations, government, or public policy); and (b) individuals included in the list should mostly do research on topics directly related to political science or most of their teaching should be on political science subjects. Besides these general criteria, country experts could use alternative criteria in accordance with the demarcation of the discipline within their country. For instance, in Italy, country experts used the official list of political scientists compiled by the Ministry of University and Research. Similarly, in France were included in the population (i) those full and associate professors affiliated to the legally recognized ‘section’ of political science at the National Council of Universities of the French ministry of Higher Education, Research and Innovation, (ii) political scientists at the National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) pertaining to the ‘politics, power, organization’ section’, plus (iii) other individuals with a PhD in political science or/and a publication track in political science affiliated to private bodies (such as private universities or the National Foundation of Political Science [FNSP]) or public ones with a status different from (i) and (ii).

The survey structure and questions on advisory and related activities external to the university is based on the dimensions of advice presented and discussed in the previous chapter. In order to map views and activities of political scientists within and across countries, indicators for the four main roles types on each of the dimensions were identified and included in a set of survey questions. Thus, the questions in the survey cover variables on types of advice, frequency of advice-giving, the degree of formality of advice, the recipients (targets) of advice, and the channels used for dissemination of advice. Moreover, the survey questions include variables on the perception of the position of political scientists at the science-policy nexus and their normative views on professional (academic) role performance. Below we present and discuss the specific survey questions, moving from motivational factors to the dimensions of advice and further to background variables to create analytical and comparative leverage for understanding patterns of advice by academic political scientists within and across countries. The survey in which these questions are included contains a larger number of items, a total of 37 questions dealing also with developments in the discipline of political science and internationalization of the scholarly community. For this reason, the question numbers do not count simply from 1 onwards, but sometimes jump between parts of the ProSEPSsurvey relevant to the analysis in this book.

2.1 Survey Questions on Professional Role Perception and Visibility

First, a set of questions in the survey was formulated for mapping underlying viewpoints on professional view and ‘duty’. Respondents were asked (Q14) whether or not they agree with a number of statements on involvement, professional obligation, working on basis of evidence, and distancing from practice. The normative views were supplemented by some statements also touching on motivations and incentives (Q5d, Q17). Career advancement as a driving factor was examined separately by asking political scientists whether they are experiencing recognition (within the country or within their own university organization) for any external professional activity. And finally, a survey question (Q1) was included for assessing visibility in the public arena: is the work of political scientists visible, and does it seem to matter? Table 3.1 presents the questions. Appendix 1 in this book contains all survey questions with the answer categories in detail.

2.2 Survey Questions on Dimensions of Advising

The previous chapter contained a discussion on the relevant dimensions of advising and on how these can be distinguished conceptually. Here we present the way in which these dimensions were turned into a set of survey questions. Table 3.2 presents the dimensions of advising.

We follow a sequence that begins with mapping frequency of different advisory activities and then moves on to topic content, recipients, and so on. Naturally, frequency of advisory activity comes with a specific kind of activity. Thus, survey question Q8 captures the repertoire of advising. For each of these activities, a frequency range was set between never and at least once a week. This combined question on types of advice and frequency addresses the central dimension of policy advising. Recall from the discussion of underlying types of knowledge in Chap. 2 that the diverse advisory activities can be about what ‘is’ (episteme), what ‘works’ (techne), and what ‘must be done’ (phronesis) (Flyvbjerg 2001; Tenbensel 2008).

Next, a second central dimension of advising is the channel used for it. Here we based our conceptualization on work of Lindquist (1990), who distinguishes between direct and indirect convocational (interactive group or presentation) settings and between direct and indirect publications, to which dissemination modes socialmedia may be added as a new and influential channel. Thus, possible channels of advising range from the more traditional publications to reports, blogs, and training courses. We extended the question on channels of advice to ask about specific communication modes, from organized settings such as conferences, workshops and so on, to face-to-face personal contacts. These possibilities are a secondary aspect of the advisory channel dimension. Related to these forms is the distinction between formal and informal advice. This distinction captures also the extent to which political scientists based at the university occupy structural positions in advisory bodies, councils and so on, or rather do advisory work in ad hoc, unregulated, and off-the-record ways. In reality, political scientists may, when engaging, not only sit on the formal side or entirely on the informal side, but also practice both ways.

Another extension of the question on channels of advice is specifically on exposure in the media. While this is a category of activity that may not be strictly speaking about delivering advice to policy makers, media exposure, certainly when initiated by political scientists, is a relevant part of visibility. It can belong to advisory role performance. But scholars also need visibility for more purely academic activities, such as ability to demonstrate impact and relevance when submitting fundamental research proposals. For this reason, we consider the frequency and nature of activity in media, from public debates to news interpretations, and from television to social online media forums such as Twitter and Facebook. We also tap whether such activity is in national, subnational, or international media.

A next dimension is the receiving end of advisory work. We argued in Chap. 2 that better than the dichotomy of supply and demand is to speak of sender and receiver. This not only follows the terminology of communication, but it also expresses that initiative for advisory activity can lay at either side. Particularly when engaging in advisory activities with a strong normative message and aiming for advocacy, political scientists are not just moving on the supply side, but also organize their own calls for knowledge transfer and dissemination. Receivers, or targets, have their own position and usually also their specific responsibilities in the policy advisory process. When orienting on categories of receivers, it is important to distinguish those with often formal competencies for policy making and delivery from actors involved in the policy process, but with an influence role rather than decision-making responsibilities. Thus, receivers of political science advice may be inside political and administrative institutions, or outside them. In Chap. 2 this was represented in the locational model of the policy advisory system. Next to executive and legislative politicians and civil servants within administrative organizations, also advisory bodies and think tanks can sit at the receiving end, as well as political party organizations, NGOs, corporate interest organizations or individual businesses, civil society organizations and grassroots citizen groups, and international or supranational organizations and institutions. Along with these different categories comes the level of governance, capturing also geographical scope: this may be national, but also subnational or international.

The final dimension of advising we include in the survey is the content, the topic on which political science scholars deliver advice. The question on topics of advice is extended to the specific area of research and expertise of respondents. Within the discipline of political science several subfields can be distinguished, both related to a substantive domain (social welfare, migration, environment, etc.) and to a broader subdisciplinary orientation and object of study, such as public administrationandpublicpolicy, which themselves may have institutionalized as a field of research and education.

In categorizing the substantive content of advice, we use the topic classification system of the Comparative Agendas Project (www.comparativeagendas.net), an ongoing international research program with scholars from different continents (see for example Baumgartner et al., 2019). The topic classification system consists of 21 main categories, from macroeconomics to civilrights, agriculture and food, public works and water management and cultural issues. The structure and operation of government and international affairs including the EU also are main topic categories. The survey includes a question on which of these substantive policy area(s) academic political scientists deliver advice. Given the central object of research in this scholarly community, the general expectation is that the structure and operation of government and international or EU affairs are prominent topics.

2.3 Background Variables for Analytical Leverage

In order to further analyze patterns of activity within the scholarly community, also background variables are included in the survey design. Thus, respondents are asked to indicate their field of specialization within the broader discipline of political science (Q16), gender (Q18), age (Q21), the status of employment (Q23), and (Q22) experience in past or present with political or administrative office outside academia.

3 Connecting Dimensions of Advice to Measuring Role Types

To reiterate from Chap. 2, the pure academic does not engage with advice-giving activities, and thus this role type barely touches any of the dimensions of advice. The pure academic thus also is the easiest to recognize empirically. It will go with rejective or ignorant viewpoints on engagement of political scientists in the political or social environment of the university. The only exposure factor of the pure academicmay be some visibility in the media to research findings and discoveries made—but not connected to engagement with stakeholders.

Our next task is to operationalize the relevant dimensions of advice and relate these to the typology of advisory roles for distinguishing experts from opinionatingscholars and public intellectuals. Given the explorative nature of this comparative project on engagement of political scientists outside their university home basis, we apply a simplified two-dimensional model for measurement and for linking respondents to one of the ideal types of advisers. The central dimension of advising we use are the various kinds of advisory activity and their frequency of use, as presented in Chap. 2 when conceptualizing advisory work.

At this point, we stress that for empirical measurement of the role types, we thus also delimit the operationalization of dimensions of advising and determine how respondents to the survey fit any of the four role types, from the pure academicto the public intellectual. This is important for two reasons. First, as the number of analytical dimensions and, therefore, variables, increases, there will be more missing observations, since one missing value in one variable implies that one observation cannot be classified. For instance, combining the variables in Q8, the main dimension in our analysis indicating type and frequency of advice, with the variables in Q13 on channels of advice would already lead to a significant loss of observations needed to determine the role type of respondents. A second and related reason is, as the number of dimensions increases, the greater likelihood of finding ‘orphan cases’—that is, those that do not meet all the requirements for inclusion in one of the theorized typologies. In order to avoid these complexities and loss of observations, we follow a simpler model and use a strategy of operationalization that allows us to link respondents to any of the four role types. Then, the information on the other dimensions contained in responses to the survey questions connected to them serve to draw up the empirical picture of orientations and activities of academic political scientists, enabling the authors of country chapters to provide a more specific analysis of all aspects of advising by political scientists within their country.

Having decided to use the central dimension of advising—corresponding to the six Q8 options in the ProSEPSsurvey presented in Table 3.2—we must now establish thresholds for measuring and determining whether the political scientists responding to the survey can be qualified as a pureacademic, an expert, an opinionatingscholar or a public intellectual. First, in order to maximize the number of usable observations, non-responses to any Q8 variable on advisory activities are considered equivalent to never offering the respective type of advice.Footnote 1Second, we develop the first type of the pure academicincluding in this category the respondents who had no advisory activity in the last three years (‘never’ to all Q8 variables). Third, the other three types are elaborated taking into account both the frequency and type of advisory tasks respondents say they have been involved in the last three years before the survey. The public intellectualtype has been constructed considering the all-round nature of their involvement in advisory activities. It includes those individuals participating very frequently (at least once per month) in at least four different types of advisory activities, one of them being ‘making value judgements or normativearguments’ (Q8_f).

The two remaining types include those respondents with a degree of involvement in advisory activities in between those of the pure academicand the public intellectual. Therefore, experts and opinionatingscholars may participate in a great variety of activities, but at a lower frequency than public intellectuals; or, they may simply participate in a more limited set of activities. The difference between experts and opinionatingscholars is set by the participation of the latter in activities involving the delivery of normative arguments or value judgments. This is made under the assumption that this kind of normative activity trespasses the usually admitted boundaries of purely technical experts (who focus only on facts and evidence).

4 The Political Science Community in the Survey

The population list of potential respondents to the ProSEPSsurvey was initially formed by more than 12,600 individuals from 37 European countries plus Israel and Turkey, so in total 39 countries. This population was depurated during the survey, excluding those individuals not active in academia anymore (some of them were deceased), those who did not work in European academic or research institutions during the survey period as well as those who had been misclassified as political scientists (in most of these cases, the individuals themselves communicated this to the survey managers). At the end of the survey, the population list was formed by 12,442 individuals (34.5 percent of whom women).

The questionnaire originally was formulated and edited in English, but in several countries (France, Greece, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Poland, Russia, Spain, and Turkey) it was translated into the main official language in order to enhance access to the survey. Respondents also were given the choice to fill out the questionnaire in English or their national language. The questionnaire was administered online using the Limesurvey software (limesurvey.org) and hosted at the Epolls.eu website (epolls.eu), and responses were collected from March to December 2018 (some late responses were received up until February 2019), with specific timings varying across countries. Everyone in the population list was invited to participate up to four times (one initial invitation plus three reminders).

A total of 2,403 completed questionnaires were received. The resulting dataset was subject to quality control, identifying problematic cases (Andreadis, 2014)—those with very short response times (below 50 percent of the average), a high number of missing responses (above 50 percent) or systematic ‘flatliners’, that is, repeating the same response across blocks of questions. After quality control, the final number of completed questionnaires was 2,354. Of the respondents, 33 percent self-identified as women, 63.9 percent as men, and 3.1 percent either preferred not to disclose their gender or did not answer the corresponding question.

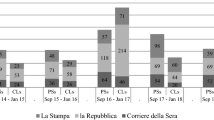

As Fig. 3.1 shows, the average response rate was almost 26 percent, though this varied widely between countries, from 7 percent in Turkey to 70 percent in Albania. Due to this highly differentiated response rate among countries and given the inevitable risk of self-selection in the responses by more publicly involved political scientists, some caution applies to presenting the survey findings as fully representative of the policy advisory activities and views of the population of political scientists. Note also that in most countries, targeted respondents were not in their earliest career stage, given the selection criteria of an obtained PhD or at least a position involving substantive research and education tasks within the department of employment. Below we will see that the average age of respondents in almost all countries is above 40 years, which increases the likelihood of some level of orientation and activity in advising compared to younger scholars who often are still underway in their PhD project.

Figure 3.1 not only displays response rates, but also the weight of the country in the total population of political scientists. This is a factor taken into account when analyzing patterns across countries.

5 Towards Country Analysis

In order to provide a background for the analyses in the subsequent chapters, in this final section we offer some basic information about the subsample of political scientists responding to the ProSEPS survey in the twelve countries analyzed in the book. We also show that information in the context of the general sample of the survey.

Figure 3.2 shows the distribution of respondents to the ProSEPS survey by declared gender, including those respondents that preferred not to disclose it. We observe that there is very little variation in the distribution of responses between the average for the 12 countries subsample analyzed in the book (hereafter called ‘the book 12-country subsample’) and the average for all countries.

Thus, the corresponding proportions of those ticking the answer ‘female’ were 32.2 and 35.2 percent, while those responding to the ‘male’ option were 65.7 and 63.5 percent. Regarding the countries in the subsample, the only country where proportions differ significantlyFootnote 2 is Denmark, were the percentages of women (21.3) and men (75.4) are substantially below and above, respectively, of the general averages. In this respect, the analyses in the following chapters will explore to what extent gender constitutes a factor affecting variance across different degrees and types of involvement in advisory activities.

Given that advice-seeking actors would probably resort to experienced scholars, it can be presumed that these are found more frequently among those admitting having participated in any advisory activities. Since experience is correlated with seniority, the relationship between age and advisory activities will be also explored in some of the chapters to come. In this respect, Figure 3.3 shows the information concerning the age of the respondents.

The average age of the book’s subsample (45.6 years-old) is quite similar to that for all countries (46.1). Nevertheless, for the twelve countries analyzed in the book, we observe some differences, visible in Fig. 3.3. There does not seem to be any geographical impact on this variable, as the relatively older respondents are in Norway, France, Denmark, and Spain, and countries with on average somewhat younger respondents are Albania, Germany, and Hungary. The other countries are in the middle.

There also is a clear association in our data between the gender and age variables. As Fig. 3.4 shows, a significantly higher proportion of women are concentrated in the younger cohorts (under 45 years of age) compared to men. Therefore, in case there is a ‘gender bias’ in advisory activities, it may reinforce the presumed age bias mentioned above. We note that for the 12-country subsample the young age category was somewhat larger compared to the whole sample in the survey. Given the likelihood of a career effect on advising, this means that our findings on advisory activities for the countries presented in this book may somewhat underrepresent the whole sample from all 39 countries.

The job position occupied by the respondents also can affect their participation in advisory activities. Younger scholars aiming at building an academic career and stabilizing their positions in universities or public research centers might prioritize those outputs that best contribute to such goal, such as publishing their research in peer reviewed journals, teaching or participating in research networks with other colleagues, while neglecting policy advisory work, which might be not so valued for academic purposes.Footnote 3

Figure 3.5 reveals that most respondents in both the book’s 12-country subsample and the general sample hold a permanent contract, with no significant differences between both groups (the proportion of permanent contracts were for the first group 75.4 percent, while the country average for the whole sample was 74.3). However, the figure also reveals remarkable differences between the countries analyzed in this book. Some of these differences are presumably attributable to the specific definition of the population used in some countries (see above), as in France, where the national experts used a legal criterion to identify most of the survey population (see above). And in other countries, such as Germany, country experts included PhD researchers in the sample since they have a formal employment relationship with the university.

In other cases, differences may to some extent reflect the underlying characteristics of the country’s academic labor market. Thus, we observe the highest proportion of temporal contracts in Germany (65.9 percent), a country where doctoral graduates experience ‘a potentially long period of insecure employment following the PhD’ (Afonso, 2016: 817). In contrast, the same proportion amounts to just 7.3 percent in the United Kingdom, a country with higher levels of job security for junior academics (ibid: 818). The same applies to other countries in the book, such as Denmark, Hungary, Norway, and the Netherlands (Eurydice_Network, 2020).

The field of specialization is another characteristic that may affect the propensity of academic political scientists to participate in policy advisory tasks. In this respect, we could expect that the involvement in this type of activities is more frequent among those scholars whose field of specialization is somehow related to a specific policy field or to the operations of actors involved in the policy process (governments, public administration, political parties, interest groups, etc.).

Figure 3.6 shows that the fields of specialization of respondents in the 12-country subsample and the whole sample again are quite similar, with the exception of politicaltheory (included in the ‘other fields’ category in Fig. 3.6), public policy, and public administration. The most frequent category of specialization is comparative politics, where the average country percentage of respondents claiming this specialization is 27.3 for the book’s subsample and 29 percent for the whole sample. It is followed by the field of international relations (18.3 and 20.7 percent, respectively). The other fields with important representation in the 12-country subsample (above 10 percent) are public policy (15.7 percent), public administration (15.3), EUstudies (13.3), and politicalinstitutions (12.6 percent). Politicaltheory is lower key in the 12-country subsample, with 9.6 percent against 15 percent for all countries.

When looking at variation between the twelve countries, some differences in prevalence of fields of specialization occur. For instance, in Italy, 42 percent of the respondents are specialized in comparative politics, while this is below 20 percent in Denmark. In public administration, there is a stark contrast between on the one hand Denmark, Norway, and The Netherlands, where some 30 percent of respondents are specialized in this field, and on the other hand countries with only a small fraction of the respondents declaring such specialization, as in the cases of United Kingdom (3.1 percent), France (4.5 percent), Italy (4.6 percent) and Germany (6.2 percent). Another point of difference is international relations, where the prevalence of this field in Turkey and the United Kingdom (30.9 and 27.8 percent, respectively) significantly contrasts with Spain (only 5.7 percent). In Spain, the difference mostly is a reflection of the traditional estrangement of international relations studies from political science in favor of international law scholars (Jerez Mir, 2010). The country chapters present these specific national developments in the broad discipline of political science and in this way, they provide the context of advisory activities of political scientists.

The last characteristic in the book’s subsample we examine is whether respondents have ever held any position outside academia. This is a variable that is also considered in some of the following country chapters in this book. This kind of experience may be related to or have impact on the advisory activities of political scientists—these positions may act as a nexus linking respondents more tightly to policy-making networks.

Figure 3.7 shows that, on average, 43.5 percent of the respondents in the book’s subsample occupies any position or has worked outside academia at any moment. This average is clearly marked by the outlier case of Albania, also the smallest of the countries in this book. Without this country, the average is 39.7 percent, which is below the average for all countries in the ProSEPS survey with 47.9 percent. The proportions are above 50 percent in Hungary and Norway, but only some 30 percent in Italy and France. Most countries in this book are somewhere between 35 and 45 percent.

With respect to the specificities of these positions, Figure 3.8 shows that, on average, they tend to be evenly distributed between positions in the public sector—either in government, parliament or public administration (22.8 percent in the book’s subsample) and organizations or groups externally to government, such as interest groups or firms, including those owned by academics themselves (23.6 percent).

In counties where a relatively high proportion of respondents have experience in an external position, this position often is some affiliation to civil society organizations or groups, interest groups, or the private sector. There is some tendency for such affiliations in civil society to become relatively more frequent when countries have a high proportion of external positions. We have considered separately the experiences of those having occupied any position in political party organizations, which amounts to an average of 9.1 percent in the book’s subsample—clearly only a small proportion of all external affiliations of academic political scientists.

6 Conclusion

This chapter presented the research design of this comparative project. Targeting the scientific political science community in Europe with temporary or permanent employment in research and education in this field, a large scale survey allows for data collection on advisory activities. Such an extensive empirical assessment of viewpoints and activities was not carried out before, and it makes it possible to place scholars in the field within the policy advisory system of their country of employment. Advisory work and the role of scientific knowledge in it have become a debated phenomenon. The focus in this project can help better understand the nature of boundary work between knowledge producers and stakeholders in the policy process. Thus, the questions included in the survey cover the relevant dimensions and indicators of advising and a number of background variables to make sense of the patterns within and across countries. With the simple model of four advisory role types as the basis, thresholds were set in order to empirically distinguish each of the advisory roles.

Overall, the respondents from the countries included in this book show background characteristics that are similar to the larger sample of respondents in the ProSEPS survey project. Most of the findings on gender, age, and academic job status are representative of the overall sample. Respondents are mostly not in the earliest stage of their academic career, with almost twice as many men than women, and a vast majority have a permanent position. There are two exceptions. The first is that respondents working in any of the twelve countries analyzed more in-depth in this book are more often specialized in public administration and public policy analysis, and less in political theorycompared to the overall sample. If this difference has any effect on advisory roles, it may be that this leads to some over-representation of advisory activities in the twelve countries compared to the other countries, as public administration and public policy may be at a shorter distance from the advisory ‘demand’ side than politicaltheory.

The second exception is that the respondents from the countries in this book have previous or ongoing positions outside the university less often than in the broader sample. While the effect of this could be contrary to the prevalent types of specialization, in that fewer external positions may go with less engagement in advising, this is first and foremost an empirical question. Engagement in advising may also be initiated and organized without any previous or ongoing position outside the university; it may even be a substitute for it. Hence, we have no strong reasons a priori to think that the book sample misrepresents the overall sample of 39 countries in the ProSEPS project.

The set of countries in this book is quite diverse—about as diverse as the complete number of 39 countries in the ProSEPS project. And this diversity is both important and necessary for the analyses that follow. Differences between the countries in this book in the properties of the scientific community may have impact on how much and how advisory roles are perceived and taken up. In fact, our general expectation is that patterns of advising vary between countries. This will be examined in the country analyses in the next part II of this book.

Notes

- 1.

A Kruskal-Wallis test can be used to compare the effect of including and not including missing cases in the composition of the typologies. The test result is notstatistically significant at the conventional level of p.

- 2.

In the rest of the chapter, when we refer to a ‘significant difference’, we mean a statistically significant difference based on either (1) for nominal variables, adjusted standardised residuals of the cross tabulations equal or higher to 2 standard deviations or equal or lower than -2 standard deviations; or (2) for continuous variables, ANOVA F-test and post-hoc additional tests (Games-Howell and Hochberg’s GT2 tests).

- 3.

However, we must note that in the recent years, the ‘impact agenda’ in research funding and evaluation set into motion in many countries by public authorities might be changing this view of policy advisory work (see Bandola-Gill et al., 2021).

References

Afonso, A. (2016). Varieties of Academic Labor Markets in Europe. PS - Political Science and Politics, 49(4), 816–821.

Andreadis, I. (2014). Data Quality and Data Cleaning. In D. Garzia & S. Marshall (Eds.), Matching Voters with Parties and Candidates. Voting Advice Applications in Comparative Perspective (pp. 79–92). ECPR Press.

Bandola-Gill, J., Flinders, M., & Brans, M. (2021). Incentives for Impact: Relevance Regimes Through a Cross-National Perspective’. In R. Eisfeld & M. Flinders (Eds.), Political Science in the Shadow of the State: Research, Relevance & Deference. Palgrave Macmillan.

Baumgartner, F. R., Breunig, C., & Grossman, E. (Eds.). (2019). Comparative Policy Agendas. Theory, Tools, Data. Oxford University Press.

Eurydice_Network. (2020). Hungary: Conditions of Service for Academic Staff Working in Higher Education. National Education Systems. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/conditions-service-academic-staff-working-higher-education-31_en

Ilonszki, G., & Roux, C. (Eds.). (2021). Opportunities and Challenges for New and Peripheral Political Science Communities. A Consolidated Discipline? Palgrave Macmillan.

Jerez Mir, M. (2010). The Institutionalization of Political Science: The Case of Spain. In G. Castro & J. De Miguel (Eds.), Spain in América. The First Decade of The Prince of Asturias Chair in Spanish Studies at Georgetown University (pp. 281–329). Fundación ENDESA / Ministerio de Educación.

Lindquist, E. A. (1990). The Third Community, Policy Inquiry, and Social Scientists. In S. Brooks & A. E. Gagnon (Eds.), Social Scientists, Policy, and the State (pp. 21–51). Praeger.

Real Dato, J., & Verzichelli, L. (2021). Social Relevance of European Political Scientists in Critical Times. European Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-021-00335-9.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Brans, M., Timmermans, A., Real-Dato, J. (2022). Strategy of Data Collection and Analysis for Comparing Policy Advisory Roles. In: Brans, M., Timmermans, A. (eds) The Advisory Roles of Political Scientists in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_3

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86005-9_3

Published:

Publisher Name: Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-86004-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-86005-9

eBook Packages: Political Science and International StudiesPolitical Science and International Studies (R0)