Abstract

In 2009, Guadeloupe experienced a historic 44 day-long strike against the high cost of living. The union-led collective (LKP) leading the strike used calculations and figures as a weapon to prove that players holding dominant market positions captured undue profits (“pwofitasyon”). Also, official price indexes were subjected to radical political criticism by the LKP actors. Yet, by using averages, these calculations could not account for the existence of individual abusive prices. The “statactivistic” momentum resulted in a shift of the legitimate price measurement methods. Calculation was, however, also the collective’s Achilles heel. LKP members’ use of numbers established only a temporary favourable balance of power in the negotiations. It was not enough for them to compete with the state’s calculative skills on an equal basis.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keyword

The historic mobilization experienced by Guadeloupe in early 2009 resulted in a 44 day-long strike, whose watchword was the struggle against the high costs of living and pwofitasyon. The social movement denounced the opacity of the state’s regulation methods and of the management of the main economic sectors, particularly in large-scale retail. The strike was led by a group called LKP (Lyannaj Kont’ Pwofitasyon—l’alliance contre la pwofitasyon), which used numbers as a weapon to analyse, claim and negotiate. Pwofitasyon is a creole word which gained prominence at the time of the 2009 conflict. The LKP collective translated it into French by the expression outrageous exploitation (“exploitation outrancière”). It means abusive economic exploitation, with the connotation that this exploitation is rooted in both colonial and capitalist relations. The Union générale des travailleurs guadeloupéens, a leftist union had already used the term in social conflicts before, since 1997 at least (Ruffin, 2009). The identification of pwofitasyon always rests on the same idea: players holding a dominant position in a given market or in an economic activity capture an undue profit, resulting from the existence of high sales prices. The denunciation of the pwofitasyon thus makes the quantified (re)evaluation of the profit or the abusive margins a passage not only possible, but also necessary.

In the case studied here, the fight against pwofitasyon resulted in a multiplication of calculation work, which was at the very heart of the 2009 movement. The essential role of figures in the 2009 struggle was not limited to the issue of price formation. The platform of protest put forward by the LKP carried a broad set of measures aimed at the revaluation of purchasing power. One of its central demands, for instance, was the introduction of a wage bonus of 200 Euros for those on low incomes. The negotiations consisted of a series of number battles around this and other demands. The parties involved in these standoffs were public institutions—the French National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE); the General Directorate for Competition, Consumption and Fraud Prevention (DGCCRF)1; the Inspectorate General of Finances (IGF); the Court of Audit; and others—as well as non-state actors urging the administrations to produce new quantitative analyses, audits and figures, such as the unions and the LKP. This ability to propose new frameworks for thinking about the economy, as well as new quantification methods was one of the strongest points of the mobilization.

How far has the “statactivist” (Bruno et al., 2014) momentum of the LKP and other non-state actors been capable of shifting the legitimate price measurement methods and the social construction of the price debate, and by what means? This is the question that this study addresses. Based on empirical observations of the calculations used during and in the wake of the movement, and analysing the conditions of their implementation as well as the discussions they triggered, this article will attempt to assess the processes by which the new measures became legitimate.

The text is organized as follows: The first part will show that the 2009 social conflict involved a variety of actors, differing in their relations to calculation and also in the quantification methods they used. The struggles with numbers lead to unequal outcomes, in which technical but also relational resources determined the balance of power between the actors. The second part will question the legitimacy of the new quantifications of high costs of living appearing in the wake of the social crisis, at a time when official price analysis and measurement studies were particularly poor. It will compare the different quantification methods under discussion during and after the negotiations: some estimates of abusive margins proposed by the LKP, which, although effective to impose a public debate on the pwofitasyon, were considered too simplistic to become legitimate; a measurement of price differences between Guadeloupe and mainland France undertaken by the INSEE, which did not sufficiently highlight abusive profits to become visible and legitimate, although it was meant to be a reference; and, finally, a practice widely used in official reports, the press, or political speeches, which selected and displayed individual prices in order to report, and denounce, the existence of abusive pricing practices. It is this latter utilization of figures which proved to be the most efficient in the public space under consideration here.

The article illustrates the shifting legitimacies of price measurements after the 2009 social conflict: the common and rigorous statistical methods used by the INSEE created controversy, because they did not display abusive prices with sufficient strength, while the innovative but clumsy quantification practices of the LKP led public actors to adopt new ways to account for pricing practices and for the price level gaps with mainland France.

The Quantification of Pwofitasyon in the 2009 Battles for Power

Quantification as a Mode of Action for a Variety of Players

The first protests leading to the January and February 2009 general strikes were triggered by an unexplained rise in fuel prices. In the French overseas départements, unlike as in the rest of France, fuel prices were administered and they were fixed via a “formula”,2 which was periodically revised, taking into account a variety of parameters, such as freight and employment costs, profit margins granted to the operators, international prices, or the USD exchange rate (according to Decree 2003–1241 of 23 December 2003) (see Bolliet et al., 2009, pp. 8–9) (Autorité de la concurrence, 2009a, pp. 4–5). The “formula” used for the price calculation was deemed to guarantee an equitable regulation of the sector, but in practice criticisms of the industry’s lack of transparency and its abusive pricing mechanisms had become stronger and stronger in the years preceding the conflict.

In 2005, an association of fishermen—the Association of Sea Fishermen of North Basse-Terre—complained that the tax free price paid by their profession had unexplainably increased by 70% between 2003 and 2005, while the all-inclusive prices had progressed much less (Gircour & Rey, 2010, p. 86). Facing the impossibility of understanding the price determination mechanisms (Les pêcheurs exigent de la transparence, newspaper article in France-Antilles Guadeloupe, 18 August 2006), their criticism targeted the regulation techniques employed by the DGCCRF. Here, the “formula” was debated for the first time outside of the administration. Then, in 2007, one of the major wholesale importers of the island, Didier Payen,3 went on a crusade against fuel supply policies and price-setting mechanisms in Guadeloupe. In a detailed study, not dissimilar to what an audit firm could have supplied, he showed that cost differentials were, at least to a large extent, due to the supply policy in place for over 40 years—a policy favouring local refining and granting a monopoly for importing and refining to a private company (the Société Anonyme de Raffinerie des Antilles, SARA)4 (Payen, 2009, p. 33). Furthermore, he showed that the calculation of pump prices contained various obvious and unjustifiable irregularities, such as the double-counting of certain taxes (as for instance in the case of the accounting for the tax on used oils) (Payen, 2009, p. 29). Although his work gave rise to discussions among the island’s economic and administrative actors in 2007 and 2008—the report was even endorsed by the Regional Economic and Social Council of which Didier Payen was a member—his intervention did not alter the methods used by the DDCCRF (regional outpost of the French General Directorate for Competition, Consumption and Fraud Prevention, the DGCCRF, in Guadeloupe), which continued to apply the same “formula” to set prices.

The social movement against pwofityason examined here arose in this context. In the first half of 2008, international oil prices rose sky high, before starting to decline in July. Yet, as the months went by, pump prices continued to rise in the various French Overseas departments. The peak was reached on 1 October 2008.5 A collective of entrepreneurs whose activities were hard hit by the increase, was the first to protest against this unbearable situation: it called for a strike in November 2008 and set up the first roadblocks in December. From the outset, Yves Jégo, Secretary of State for Overseas territories, showed himself to be receptive to the protest movement’s messages. He, too, was somewhat suspicious of the administration’s way of regulating the oil sector, which he considered opaque and potentially collusive (Jégo, 2009, p. 89).

In December 2008, the Inspection Générale des Finances (Inspectorate General of Finances, IGF) was asked to investigate the situation, and the Competition Authority was seized in February 2009. Pending the conclusions of these audits, the State adopted transitory measures, applying an immediate 31 centimes reduction per litre for lead-free petrol, and a 22 centimes reduction for diesel (Guadeloupe: An agreement to reduce oil prices triggers the removal of the roadblocks, 2008). To compensate SARA’s loss of income, the agreement reached with the collective of entrepreneurs also provided for temporary State transfers to the company. Far from appeasing the social situation, the agreement actually fuelled the conflict: The Lyannaj Kont’ Pwofitasyon (LKP), the alliance against pwofitasyon, was set up on 5 December 2008 upon the call of the Union Générale des Travailleurs de la Guadeloupe,6 the main Guadeloupian trade union, which was completely opposed to the State’s compensatory transfer to SARA. The very object of their anger were precisely the profits made by the company, which they considered to be illegitimate, i.e. pwofitasyon. Hence, it called for a general strike on 16 December, the day after the agreement was signed with the entrepreneurs (Gircour & Rey, 2010, p. 97).

LKP’s accusations were incomprehensible to the administration, which denied any fault. The “formula” may of course have been clumsy, since price revisions were not frequent enough to guarantee a good matching of prices at the pump with international market fluctuations. However, according to the administration, no collusive or irregular practices occurred,7 and despite the existence of certain dysfunctionalities, price regulations had mostly suffered from a lack of adequate consumer information. The March 2009 General Inspectorate’s report confirmed these assertions. But it also acknowledged that the complexity of the “formula”, and its outdated character, had made fuel prices opaque and vulnerable to calculation errors. The impact remained low, however: only 8 centimes were due to these errors, that is 5% of the price, and not 40%, as asserted by Payen.

LKP’s call for a strike was, however, the starting point of a wider movement. The radical trade unions, UGTG (Union générale des travailleurs guadeloupéens), CGTG (Centrale des travailleurs unis) and CTU (Confédération générale des travailleurs de Guadeloupe), aspired to start a general strike on a broad set of claims going well beyond oil prices. Between December 2008 and January 2009, the collective prepared a broad platform of protest comprising 165 points.8 The denunciation of pwofitasyon and the issue of purchasing power formed the platform’s base (Ruffin, 2009).9 The reasoning justifying the denunciation of fuel prices was replicated in numerous sectors, considering that prices were seen to hide abusive margins more generally: the LKP thus drew attention to the possibility of abuses on the markets for “basic necessity items”, such as transportation, water, rents, electricity, communications, etc. To address this situation, the collective demanded the adoption of a variety of measures: the promotion of transparency, both in the private sector and public services, for example through the conduct of a programme of audits, or the creation of a “workers’ research office” (Bureau d’études ouvrières, BEO) intended to help trade unions monitor prices; the bolstering of purchasing power via a series of social transfers to households (the symbolic claim being a bonus of €200 for all employees below a certain level of salary, and other claims pertaining to an increase of the social minima); interventions on price formation (the LKP demanded for example a “significant reduction of all taxes and margins on basic necessity products and on transportation” as well as the freeze of certain prices, such as rents and fuel); the fight against the pre-eminence of the importing companies and the promotion of Guadeloupian products.

What does the above teach us about the role of calculations and figures in the formation of social and political relations in Guadeloupe? Economic calculation played several roles here. The mobilization was aimed at fighting against the social and economic relations which calculation had helped establish (for example, the determination of fuel prices through the “formula” had immediate and daily consequences for the entire region). Besides, various actors turned calculation into a weapon, mobilizing their analytical capacity to denounce or even accuse the private firms and public administration of abusive pricing practices. Lastly, calculation was used by administrative and political players who carried out audits and controls in order to promote transparency and arbitrate the conflict, making calculation also a mediation tool.

Moreover, social actors stood out by their plural use of calculation and differed in their position with respect to the handling of figures. For the administration in charge of regulating the fuel sector, the handling of the “formula” echoed a routine task of “government at a distance”. The interviews I conducted showed that the executives in charge were concerned with professionalism and accuracy, while being subjected to strong pressure by the economic actors. Since the existence of calculation errors was somehow part of the routine in their eyes, they also demonstrated the administration’s relative indifference towards citizens (Herzfeld, 1992; Hibou, 2012, pp. 128–129). For some executives also, the handling of the formula could possibly reflect the collusion with the operators of the oil sector, who were seeking to draw maximum profits from the framework established by the “formula”, but this could not be proven.10 Here, different players used calculations and economic analysis to denounce the arbitrariness and opacity of price management. Didier Payen decided to undertake his own investigation of fuel price formation, making large use of quantification and collecting information via his personal network. His task was difficult: his report underlined how it had not been easy to obtain relevant information‚ the administrations hardly being open to his interrogations. Nevertheless, he belonged to an economic elite that had some access to information and power circles and was also able to spread his message. His report was even published by the regional Economic and Social Council.

This was not the case for the fishermen, who a priori turned out to be the victims of the calculation’s arbitrariness. By initiating an inquiry into the “formula”, they seemed to fight David’s fight against Goliath, but while facing the opacity of price determination, they finally obtained some pieces of the puzzle of the fuel sector’s management. Central political and administrative authorities could also act as counter-powers to the local authorities: The State Secretary, and the supervisory bodies questioned the way the figures were used, claimed their right to inspect and audit the data, and reaffirmed their capacity to impose sanctions in cases of proven circumvention of the rules. Finally, by demanding the end of pwofitasyon and claiming the existence of abuses, the LKP’s relation to data was two-sided: they expressed doubt and uncertainty as to the integrity of the calculation methods and considered it was a sufficient reason to challenge the legitimacy of power practices, and to enter into a struggle with the administrative authorities. Furthermore, later events of the movement (see also the next section below) show that the collective used calculation as a weapon and an accusatory tool, even when it could not prove the existence of abuses.

Thus, there are different styles of calculation, which are characterized by varying capacities of actors to master calculation techniques, varying access to information, varying relationships to the political authority and different motivations in making the calculations.

These varying styles of calculation also reflect different historical trajectories. Didier Payen, in particular, was not only interested in social dialogue and defending his own entrepreneurial interests: he was a member of MEDEF and acted in his capacity as a representative of heads of businesses; he was also a notorious supporter of free market ideas. He highlighted the virtues of free trade continuously, and disputed the regulatory measures taken by the French authorities. His calculation techniques expose this multi-layered social and political position, for example he mixes the writing of pamphlets with the work of an audit. His approach was not that of an auditing firm, as can be observed immediately from the style of presentation: large characters, flashy colours to highlight the most important findings and underline the denunciative tone. His approach was reminiscent of the correspondence between chambers of commerce and the administrative authorities during imperial times, when merchants and settlers from the islands challenged state decisions in order to obtain free marketing rights (Lemercier, 2008; Tarrade, 1972, pp. 224–285).

The LKP’s and unions’ calculation techniques also deserve to be questioned from a historical standpoint. The use of calculation and technicity for purposes of activism must be considered in the light of the specific history of unions in Guadeloupe, and of their relations towards the administrations.11

The Role of Technicity and Expertise in the Negotiations

The struggle breaking out in January 2009 with the general strike showed that LKP’s actions related in a variety of ways to state administrations and to the logics of expertise. On the one hand, the collective’s skill and capacity enabled it to negotiate with the State on its own ground, in particular, because some of its members stemmed from the administration. The collective also had close links with most technical administrative bodies, such as the INSEE, which could support the activists during the negotiations with their expertise. Nevertheless, the negotiations were also an unequal process, in which highly skilled negotiators from the State’s Overseas department cabinet in Paris succeeded in getting the upper hand over LKP’s leaders, who did not have the same access to economic information, and who did not enjoy the same calculative skills when it came to the design and discussion of new public policy instruments. Such observations ask for further investigation of the links that these “statactivist” (Bruno et al., 2014) mobilizations maintain with state administrations and expertise. Historically, both unions and employers’ organizations fought to impose their conceptions of quantification, and they employed quantitative skill in their struggles; yet, they were also often backed by statistical administrations (Stapleford, 2009; Touchelay, 2014; Volle, 1982). What kind of situation is reflected by the Guadeloupian case? What kinds of links between the LKP’s activist use of numbers and administrative expertise can be uncovered in this instance?

Thanks to the protests, LKP quickly met with resounding success. After the indefinite general strike which was launched on 20 January 2009, a series of important demonstrations began (Calimia-Dinane, 2009). On Saturday, 24 January, and Sunday, 25 January, over 10% of the island’s population are said to have marched in the streets of Pointe-à-Pitre. The Prefecture, impressed by these successes, agreed to enter negotiations. It also took a decision for which it would later on be much blamed by the State’s Overseas department: the Prefect agreed to a live television broadcast of the negotiations (Jégo, 2009, p. 54). The live broadcasting by Canal 10, from 24 to 28 January, was an unprecedented event. Thanks to their skills and mastery of the economic and social issues under discussion, the LKP members stood up well to the Prefect and his administrative directors. On each of the points up for negotiation, the administrative directors—often coming from mainland France like most in the state administration hierarchy, and in Guadeloupe for just a few years—faced union members who had managed to build solid knowledge of the files over many years. At that time in Guadeloupe, both among activists, the administration, the negotiators and the press, the LKP was praised for its skills, and placed on a pedestal, whereas the administration was allegedly found to have been incapable and at fault. The course of the negotiations confirmed LKP’s victory. The televised discussion was interrupted early, on an order from Paris. Prefect Desforges read a message from the State Secretary Yves Jégo denouncing the way the negotiation had been turned into a “tribunal” (Jégo, 2009, p. 54). And Yves Jégo decided to come to Guadeloupe in person to settle the matter.

At the beginning of the strike, the movement thus succeeded in gaining the upper hand over the state players by demonstrating its ability to use “government tools”, such as administrative files and techniques of economic calculation (Desrosières, 2008, p. 59). This evidences a profound transformation of the modes of political action in the Département. After the violent struggles that had occurred during the 1970s, which included armed and terrorist action,12 since the 1990s, the left-wing anti-establishment and separatist movements moved onto different institutional ground (Daniel, 1997; Réno, 2001). Its leaders, many of whom were born after Guadeloupe’s “Departmentalization”, got to know (and to challenge) the state apparatus from the inside. The separatist parties became very successful in local elections by asserting their management abilities, while facing a political class seen as corrupt and unreliable. This shift, however, remained limited to political parties only. The main unions within LKP, such as UGTG and CGTG, continued to present themselves as the legatees of the radicalism of past struggles. Continuing to refer to the traumatic memory of the great repressions of the 1960s and 1970s, such as the May 1967 episode, when police fired at crowds, resulting in a number of victims, still kept secret to date by the French State,13 these unions continued to use force and inflexibility as weapons, sometimes even advocating resort to violence (Braflan-Trobo, 2007).

Yet, the use of such radical methods generated a deep division among trade unions in present-day Guadeloupe. Major strikes had often resulted in a divided society. In this respect, LKP’s approach marked a break. The trade unions united with political parties and a number of associations to form an unprecedented alliance (Bonilla, 2010; Bonniol, 2011, p. 92; Chivallon, 2009; Gircour & Rey, 2010, p. 101; Larcher, 2009). The LKP could take advantage of a generational renewal. By grouping officials from different economic and social sectors, customs officers, company executives, political leaders, academics, representatives of consumer organizations, etc., it benefited from the arrival of union leaders who came from the very heart of the bureaucratic and political system. Elie Domota, head of LKP at the time, and originally from UGTG, the main Guadeloupian autonomist union, was for example deputy director of the ANPE in Guadeloupe. Alain Plaisir, the collective’s economist at the time, was a customs officer with a thorough knowledge of economic policies and the tax system. Thus, LKP was in a position to initiate the struggle via the administrative field itself. It was comfortable with the handling of figures and administrative data, presenting itself as the institutions’ interlocutor. In this respect, the movement can be seen as a “XXIst century movement”.14

Nevertheless, only a few months after the mobilization, the initial impressions of success started to fade. The idea that the LKP could play on an equal footing with the public administration thanks to its skills was contradicted by the observation that the movement—with its limited means—was facing a dominating State apparatus. In many respects, the fight was unequal. A closer look at one of the negotiations helps to get a sense of the multiple factors shaping the power relations that developed between by the LKP and the other parties around economic policies. The negotiation of the wage agreement resulting in a €200 bonus for workers earning less than 1.4 times of the SMIC (guaranteed minimum wage) affords in particular a better understanding of the movement’s relation to economic and statistical expertise.

The negotiation involved the State, the local authorities and the social partners (trade unions and heads of businesses). It took place shortly after the adoption of a new social system in France, called the “active solidarity income” (Revenu de Solidarité Active, RSA), which provided a bonus to all persons whose income was below the minimum wage. But this system had not yet been applied outside mainland France, in spite of repeated appeals from the overseas departments’ elected representatives (Le RSTA moins avantageux que le RSA? Newspaper article, France-Antilles Guadeloupe, 15 May 2009). The negotiation’s aim was to determine the overall financial effort that could be made by each of the parties (region, regional council, State and companies) in order to pay a bonus. The total amount obtained would determine the salary threshold below which the bonus could be paid, and therefore the number of beneficiaries. The first phase in the negotiation had made it possible to find an agreement close to the wishes of the LKP. Under the auspices of Yves Jégo, the MEDEF accepted that the bonus would apply to all employees earning less than 1.6 of the SMIC (guaranteed minimum wage). But the State secretary was disavowed by the government and the agreement was adjourned before it could be sealed and signed, probably due to pressure from the lobbies of heads of businesses in Paris (Jégo, 2009, p. 11). Because of this U-turn by the government, the unions’ position became more extreme, and tough, even clearly violent, methods propagated by certain radical fringes of the LKP, such as Alex Lollia’s “GTL” (Groupe d’intervention des travailleurs en lutte) (Gircour & Rey, 2010, p. 14), emerged at this point. Shops were closed by force to comply with the general strike order; extremely tough road blocks took place, night-time violence, lootings of shopping centres, clashes with police forces erupted, even causing the death of a trade unionist, Jacques Bino, who was shot dead near a roadblock during the night of 18–19 February (Gircour & Rey, 2010, p. 123).

In the midst of this tense situation, a team of negotiators was dispatched from Paris by Matignon. The discussions turned into a tug of war. The LKP refused to go beneath the threshold of 1.6 of the SMIC (guaranteed minimum wage), which it considered had already been obtained during the first negotiating phase. The other parties could not, or did not wish to, finance the total sum. At this point, the discussions placed calculations at the centre of an open conflict, and INSEE’s (National Institute for Statistics and Economic Studies) regional office played an important part in the mediation. It lay the foundations for the conduct of the discussions, by supplying all parties with the figures required for the calculation of various scenarios, in particular figures concerning employment and the distribution of income by branches.15

INSEE’s regional office was in direct contact with the negotiators, often quite informally. On LKP’s side, Alain Plaisir, the collective’s “economist” (and also Secretary General of the Centrale des Travailleurs Unis, CTU) communicated with INSEE’s regional office, sometimes directly from the negotiation’s backstage. The delegation of negotiators could present its requests to the INSEE internally through the administrative channel, either directly or via the Prefecture’s services. The negotiations were concluded on 26 February 2009 with an agreement which was constructed on the basis of the calculations realized by the statisticians.16 The negotiations were based on calculations simulating the financial impact of a €200 bonus on a variety of economic branches, and the collection of available information for this. Such work was of course technical. But the statisticians’ work also contributed to the political mediation of the conflict. INSEE’s regional department head was considered by the Paris negotiators to be part of the state administration and, off the record, he was an attendee of internal meetings held at the Prefecture. Such an integration was quite unusual, since INSEE’s mandate of independence would normally require that it remained distant to the work of the Prefecture.

In parallel, a close link could also be established informally between the LKP and the INSEE. The CTU’s union representative within INSEE, a statistician himself, knew that he could count on his department chief’s cooperation during the negotiation. Sometimes, the LKP and the INSEE would even discuss urgent matters by telephone. Thus, the social dialogue relied on links that each party managed to establish with the INSEE, which on the one hand assisted in elaborating measures of economic policy based on quantitative data, and, on the other hand, sought to act in a mediating capacity in the conduct of the social dialogue.

Despite the existence of such a political mediation through numbers, the relations between the parties remained conflicted and unequal. The events following the agreement show that the process carried numerous uncertainties. The agreement turned out a posteriori to be much less favourable to LKP than it had seemed to be at the outset, because the collective had contented itself with too vague terms. In fact, the State had merely redeployed funds that had already been budgeted for a similar scheme, simply re-shaping old policy measures.17 The 1.4 SMIC limit also created confusion as to whether the threshold amount was net or gross, which made the agreement actually more restrictive than it had appeared. As a result of the bonus, certain households passed into a higher tax bracket, thus reducing the sum they were expected to receive overall (Le RSTA moins avantageux que le RSA? Newspaper article, France-Antilles Guadeloupe, 15 May 2009; Verdol, 2010, p. 63). Lastly, from the end of the first year onwards, the system was no longer fully financed. It thus turned out that the social negotiation had been less favourable to the collective than it had seemed, in particular because the other negotiators had been better armed than the LKP to deal with the files and the evidence contained in them.

These different sequences show the multiple roles technicity and calculation played in the social dialogue and the struggle against the high cost of living in Guadeloupe. In the negotiations examined above, the LKP had indeed succeeded in imposing the establishment of new public policies, even if the State services, initially taken by surprise, were able to regain the upper hand. The collective showed that it was possible to defy the State’s power on its own ground, and even to get the existing policies shifting. But its activism was also subject to an unequal relation. This raises the question whether or not, observing the ways in which economic policies were formulated before and after the conflict, LKP’s activism succeeded in creating a lasting change in the relations of power in Guadeloupe.

The Legitimacy of Price and Margin Measurements

Did the conflict modify the calculation of prices and quantification and assessment of (high) living costs? Did the LKP succeed in making its voice heard, by changing the socially accepted methods of measurement, in the short and in the longer term? To answer these questions, this section will examine the means by which the unions’ action and the social movement legitimized, or de-legitimized, new price measures, as well as ways of thinking about the question of high cost of living.

The Absence of Prices and Margin Measurements Before 2009

Prior to the 2009 crisis, the measurement of prices was in a paradoxical situation. In the French Overseas departments, the debate on price formation was at the centre of attention and socio-political relations, and the high level of prices was recurrently denounced. And yet the question of price levels gave rise to very scarce economic analyses and statistical follow-up efforts. One of the consequences of the 2009 movement is the questioning of this status quo in which the price question remains outside the scope of what can be discussed by public institutions.

When purchasing power became the centre of attention of Guadeloupe’s boiling political scene in 2009, INSEE’s most recent studies on the cost of living differential between mainland France and its Overseas departments (DOM) were surprisingly old. The last one dated back to 1992, and the one before that to 1985. Such deficiency surprises, because conducting such studies is theoretically required and constitutes a core part of INSEE’s working programme. Once every ten years at least, INSEE is supposed to establish a “geographical price comparison” for the State to adapt a series of public policies towards the Overseas departments (DOM): in particular, the level of the bonuses granted to civil servants to make up for the cost of living gap (the famous “sur-remunerations”) and other social transfers, such as the “territorial continuity” which subsidizes transportation to mainland France. In other words, price differentials between the different DOM and mainland France constitute key data for the State, but when the contestation broke out in Guadeloupe, INSEE had not measured them for a long time.

It is difficult to assess precisely why such a situation prevailed. The debates following the adoption of the Euro in 2002 were for sure a part of the explanation. The adoption of the Euro generated in particular very strong discontent in the Overseas departments (DOM). In the DOM, and to a lesser extent in mainland France, the changeover to the Euro was deemed to have entailed particularly heavy price increases, especially in the large-scale retail sector. Such increases could not be formally proven by existing surveys in Guadeloupe, but interviews with INSEE officials confirmed that closer scrutiny of the price factors could have revealed and confirmed these. INSEE’s official speech, however, buried these increases inside an assessment of the general level of prices, which allegedly had remained stable (INSEE, 2002). The lack of official statistical data became the object of a public debate.

In La Réunion, where the price gap with mainland France reached 70% to 80% on many supermarket products at mid-decade (UCF/Que choisir, 2004, 2005), the pressure exerted by elected representatives and consumer groups sought to reinforce the establishment of better price analysis structures. Thanks to the relentless fight of a communist elected representative of La Réunion,18 the decision to create regional price observatories in Overseas departments (DOM) had been adopted in 2000. These observatories would bring together consumer associations, administrations, social partners, chambers of commerce, etc., under the presidency of the Prefect. But until the controversy over purchasing power grew on the island in 2004–2005, the resistance of state services remained very intense (Sénat, 2005, p. 1725). According to witnesses of the creation of the observatory, this reluctance could be linked to the pressures exerted by the large-scale retail sector lobby (Le collectif pour l’observatoire des prix: Dix mille signatures pour Baroin, newspaper article, Le Quotidien de La Réunion et de L’Océan Indien, 5 September 2006). The implementation decrees were only adopted in 2007 (Doligé, 2009, p. 147).

In Guadeloupe, the price observatory held its first meetings in 2008, and its activities were expanding when the conflict erupted. The observatory intended to conduct a whole new series of analytical works, but at least during the first years of its existence, it had not been able to produce any important results (Favorinus, 2009).

The public authorities’ reluctance to (re)calculate and analyse prices should also be understood in the light of the Overseas departments’ social history. The matter is explosive and had caused the periodic resurgence of historical disputes. One matter was particularly explosive in this context: the 40% bonus (sur-rémunération) granted to civil servants in Guadeloupe, which they managed to obtain in 1953 following a tough fight and a 65-day strike. At that time, only mainland civil servants were granted such bonuses (similar to the compensations paid to the civil servants accepting to work in the colonies), and even when Guadeloupe had become a department in 1946, the native civil servants were not entitled to this premium (Dumont, 2010, p. 170).19 Since then, and although the level of the sur-rémunération should theoretically be indexed to the observed level of prices (measured by the gap with the mainland), discussions about the adjustment of the bonus were often very risky, because they carried with them the nagging and conflictual question of equal treatment within the Republic, which became effective only recently (Burbank & Cooper, 2010; Forgeot & Celma, 2009; Mam Lam Fouck, 2006).

In theory, the price gap observed in 2009 could no longer justify a 40% bonus: INSEE’s studies of 1992 placed the synthetic indicator at around 12%. Since the beginning of the 1990s, there had been regularly calls for a reform to reduce the sur-rémunérations (Doligé, 2009, p. 147; Fragonard et al., 1999; Laffineur, 2003; Ripert, 1990), but these recommendations, issued in Paris, never became effective, with the spectre of revolt apparently still on everybody’s mind. In addition, the sur-rémunérations also played an implicit redistributionary role in a situation of great poverty prevailing in the Overseas departments (DOM: le Medef remet en cause la sur-rémunération des fonctionnaires, newspaper article, Journal de l’ile de la Réunion, 11 August 2010; Sur-rémunérations, des avis plus contrastés à la Réunion, newspaper article, Journal de l’ile de la Réunion, 12 August 2010), all of which made it a very sensitive subject.

In La Réunion, the inopportune release of a price study resulted in a very serious social unrest in 1997, as well as a “civil servants’ revolt” (Conan, 1997). My interviews suggest that INSEE, by omitting to carry out this task in Guadeloupe for almost twenty years, avoided taking up a position on a question its officials felt was politically too sensitive. But in doing so, it also took the risk of having to react under pressure by starting a study at the very moment the debate would truly flare up.20 And this is precisely what happened in 2009. To be exact, this position is in no way indicative of the statistics policy in the French Antilles, which rather tends to be maximalist, because there is a recognized need for more precise data on the départements’ economies (Morel & Redor, 2008; Rivière, 2009; Sénat, 2009). Nation-wide surveys are often over-sampled to ensure their representativeness at the level of the département, and sophisticated macro-economic aggregates (regional accounts) are compiled. All in all, it can be held that on the eve of the conflict, the absence of price data was both the symptom of the conflictual nature of the matter in the public sphere and the impact of the status quo on the politics of distribution (symbolized by the pursuit of the sur-rémunération policy) which was also an obstacle to frank reflections on price levels on the island.21

This observation also relates to the surveillance of margins and competition practices, in particular in the mass-market distribution sector. The pricing practices of economic empires, such as those of Bernard Hayot or Alain Huyghues-Despointes, both “békés” (Antillean Creole term to describe a descendant of the early European, usually French, settlers in the French Antilles) from Martinique, were at the very heart of the 2009 protests. Mass market and import fortunes were built in the West Indies during the 1970s, with the help of state-sponsored policies. Coming from the plantation economy, merchants and other entrepreneurs found in the “catching-up” policies in place from the 1960s through to the 1980s numerous opportunities to save their assets from the historic collapse of the sugar-cane sector in the 1970s, in particular by taking advantage of the public subsidies supposed to stimulate investment in the new markets and sectors, such as tourism, or large-scale retail. These programmes generated windfall effects, as well as misuses and excesses. The negative consequences of these policies were discussed at length by the parliament (Jalabert, 2007, p. 75; Ripert, 1990).22 And yet, though recurrent since the mid-1990s, the numerous calls for a serious re-evaluation of the défiscalisation (tax exemption policies), which were a continuation of the systems initiated in the 1960s, had never been successful. Recently the French Court of Auditors (Cour des comptes) and the Economic and Social Council (Conseil économique et social) took once again an interest in the question, but their recommendations were not implemented either.

In the same vein, since the DGCCRF lacked human and logistic resources, its agents undertook no serious study of competition struggles on the Islands, although such studies would have revealed the dominant position the main actors had managed to build in the large-scale retail sector (Doligé, 2009, pp. 132–133).23

The tense status quo around economic policies extends to economic analyses, measurements and evaluations of prices and margins, which remained understudied until the end of the 2000s. The 2009 struggle, with the massive general strike and the roadblocks which paralyzed the Island’s economic activities for 44 days, got things moving. The social conflict and the existence of LKP’s platform of protest forced the opening of a participatory debate, in particular through the organization of a large multi-stakeholder consultation under the auspices of the State’s Overseas department (les Etats généraux de l’Outre-mer, from March to July 2009) which was followed by the establishment of an Interministerial Committee for Overseas Departements (Comité Interministériel pour l’Outre-Mer). In this context, the group working on price formation, purchase power issues and large-scale retail issued a series of recommendations largely inspired by LKP’s claims. The group was headed by a former chief of the Guadeloupean regional office of the INSEE, Delile Diman Antenor, who was also very respected by LKP members for being a former leftist activist. The report produced under her guidance proposed the conduct of new economic and statistical analyses, enabling the setting-up of a fully fledged “transparency policy” in response to the social movement.

The particular measures provided in the agreement of the 4th of March 2009, which put an end to the general strike, included studies that were to be undertaken by the INSEE, the DDCCRF, the Price and Income Observatory, or workers’ associations, such as the “Bureau of Labour Studies” (BEO) (see Protocole d’accord du 4 mars 2009). The “typical shopping trolley” and the “household shopping basket”24 were meant to permit price tracking (and adjustment) in the large-scale retail sector. The spatial comparison of prices between mainland France and Guadeloupe conducted by INSEE was intended to evaluate the price gaps. The programme of competition audits to be undertaken by DDCCRF was destined to shed light on the practices of certain strategic sectors. In addition, a study of consumption patterns was to be launched, with the aim of boosting local production. Furthermore, the creation of a regional commission for economic and statistical information (CRIES) was considered (Diman-Antenor, 2009). These various studies were furthermore slated to be submitted to the Price and Income Observatory (Observatoire des prix et revenus). At least on paper, the response to the problem of purchasing power appeared to be ambitious and coherent.

However, studying the transformation of the ways in which prices were managed by numbers requires to go beyond examining the presentation of these plans on paper. The problem lies not so much in the questioning of the effectiveness of the implementation of this “transparency policy”—a large portion of the measures has been more or less implemented since 2009. It is about examining whether the price measurements gave way to new social practices and formed a base for new measurement conventions, which could be either seen as legitimate, or, on the contrary, as sparking debates and controversies. To examine these questions, the remainder of this chapter will investigate how three different modes of price quantification were used and put up for discussion. Firstly, the chapter will analyse negotiations of “voluntary reductions” of the prices of the products considered as “necessities” (produits de première nécessité), where LKP used very intuitive, but not very robust commercial margin estimates. These calculations became quickly delegitimized for their lack of precision, but they also helped improve the balance of power as they generated a debate on what constitutes legitimate levels of prices and margins. Secondly, the case of the spatial price comparison study carried out by INSEE is considered which highlights how a sophisticated study, evaluating the price gaps between Guadeloupe and mainland France, can come to be very negatively received and held to be socially and politically illegitimate, although such a study had been among the social movement’s core demands. Lastly, by examining a diverse series of studies of prices and margins, I will argue that new legitimate price-setting practices eventually emerged. However, neither the price index nor the average price level measurements stood out as proper ways to address issues related to high living costs; rather, extreme values, such as examples of individual high prices, seemed to be better able to reflect the population’s feelings of inequality and injustice in the face of abusive pricing practices. Here, new quantification methods took root as legitimate ways to describe and denounce such pricing practices.

The Quantification of Pwofitasyon: Innovation and Tests of Reality

The negotiations held to determine price reductions for the 100 products knowns as “necessities” reveal LKP’s working methods, its approach to obtain margin reductions and its use of figures.

The negotiations were held from March to May 2009 under the supervision of the Prefecture (Préfecture) and the DGCCRF, and they were particularly tedious. One hundred product families were designated; a set of products had to be selected for each of these families. The various actors of the large-scale retail industry had successive discussions with the LKP, from local minimarket chains, such as Huit à Huit, to the very large Bernard Hayot Group. Every day discussions were held, from late afternoon to four o’clock in the morning, over a period of approximately three months.25

The collective of the LKP intended to get the upper hand by showing quantitative evidence (or at least what it held to be such evidence) of the existence of pwofitasyon and of the necessity to lower prices and margins. This was possible thanks to the series of calculations on prices it had carried out prior to the negotiations.26 At that time, there was no other available information on commercial margins in the large-scale retail sector. No public institution could be blamed in this respect, since only a detailed audit of the sector, or a competition audit could have produced solid facts about profit margins, and such actions, though within the DGCCRF’s competence, were not deemed necessary to be undertaken on a regular basis at that point.27

The technique the LKP collective had adopted under the guidance of its economist, Alain Plaisir, was rudimentary, but it made it possible to put a figure on the table. LKP teams prepared listings of prices observed in mainland France, using the Carrefour chain’s website; for each product, a theoretical DOM price was then calculated by adding a fixed percentage to the mainland price to account for the costs of transportation, taxes and other logistics. The members of the collective considered that these costs could be estimated by adding a lump sum of 10% to the initial price. The resulting theoretical prices were then compared with the prices that were actually observed in the island’s supermarkets; and the resulting differences equipped the LKP with estimates of “illegitimate margins” picked up as pwofitasyon by the companies.

LKP’s ambition was at least twofold. First, it sought to expose the illegal profits, and, second, it used the figures in its price setting negotiations. Each brand brought its own price records and negotiated item by item. Armed with spreadsheets, the LKP thus cornered the large-scale actors and obliged them to justify the level of their commercial margins (see also Fig. 11.1, which provides an excerpt from the records that were used by LKP in the negotiations). Obviously, the method the LKP applied was very clumsy, and the obtained values were impossible to verify. Nevertheless, the figures reflected LKP’s mental representation of the price formation, and they rested on the collective’s “expertise”. They were thus considered significant enough to uncover misuses and force the concerned players to admit their abusive pricing practices and to lower their prices.

The method worked. The negotiations led to a series of agreements providing for price reductions on the 100 “necessities”. These agreements were binding for the companies concerned and gave rise to new control procedures. Announcements of price reductions had to be displayed visibly in all stores. The DGCCRF was in charge of verifying the enforcement of the agreement. It was also responsible for the monthly publication of a survey on large-scale retail prices. The negotiations thus led to actual results. However, at the same time, the LKP was taking a big risk by employing such a simple method. This could easily engender powerful resistance, as the figures could easily be invalidated. Both actually occurred very quickly.

The “quantification” of pwofitasyon proposed by the LKP was rapidly contested. Their use of numbers entailed certain weaknesses which came to be exposed in the course of the negotiations. Rather than proving the high level of prices, the numbers were also used to constrain companies to lower the prices.28 Although some of the negotiators had true expertise in price formation, as for instance Alain Plaisir of the CTU union or Justina Favorinus of the Consommation, Logement et Cadre de Vie association, the negotiations revealed that LKP had missed some major components of price formation in their calculations. LKP’s theoretical prices were thus grossly underestimated, so that some firms came even to be obliged to sell at a loss. According to members of the LKP, the unions became only in the course of the negotiations aware of this and the fact that a major part of the commercial margins escaped mass-distribution operators, and were instead distributed to other actors, such as importers and wholesalers. The important role of these actors had not been identified by the LKP experts before. More generally, the sharing of “gross margins” among a myriad of participants had never before been perceived by the analysts as a major cause of high prices (Favorinus, 2009). For a while LKP considered inviting these other actors—distributors, wholesalers, logistics and warehouse operators—to the negotiation table as well. But this turned out to be unfeasible, since this would have entailed more than 300 companies.29 Therefore, the negotiations on necessities had to be stopped in the face of this obstacle.

In an apparent paradox, by undertaking efforts to quantify price differences and margins, the trade unions had made it possible for themselves to better understand the formation of prices, but such better understanding made it in turn impossible for them to demand a significant lowering of prices. LKP’s initial analysis of prices had proven inaccurate. The pertinence of the notion of pwofitasyon, understood as the grabbing of commercial profit by a very limited number of actors, was also seriously challenged. Nevertheless, the negotiations brought the quantification of price formation to the centre stage of the public debate.30 From this standpoint, it cannot be considered that LKP did not succeed in undermining the long lasting status quo around pricing practices.

An Expected but Socially and Politically Unacceptable Intervention by Public Statistics

The case of the work known as “spatial price comparison” produced by INSEE (Berthier et al., 2010) was the exact opposite of the situation described above. This study was supposed to be the highpoint of the “transparency policy” initiated in response to the social crisis. But although the study managed to finally quantify the price gaps with mainland France, thereby officially acknowledging the existence of such gaps, it failed to become the “instrument of proof” it should have come to be (Desrosières, 2008, p. 59). On the contrary, the study became an occasion for heated exchanges and controversy among the actors of the conflict.

First of all, the INSEE study was published relatively late, in July 2010, i.e. roughly sixteen months after the open conflict had ended. Its release had been postponed after a debate that had ensued among INSEE’s specialists, and for the reason of being able to use what was considered to be the best-suited, but also cumbersome method: the purchasing power parity (PPP) method of comparison. A reference method used in international organizations (for instance, the International Comparisons Programme carried out under the auspices of the United Nations has used it since the 1970s),31 PPP calculations mobilize expertise composed both of national accounting and price statistics. The head of the regional statistical office of Guadeloupe in particular had argued in favour of this methodology. Yet, in the end, the investment was deemed too costly and unwarranted in Paris, so preference was finally given to a much lighter method based on the data that had already been collected for the price indexes.

There were two good reasons behind opting for such a technique: first, the existing databases used for the calculation of price indexes immediately allowed for this type of analysis, no additional data collection was required; second, the method appeared completely natural and clear to the price statisticians in charge of the study, who, however, were not really at ease with the complex analyses of purchasing power parities. The choice was thus apparently technically driven, marking the reluctance of price statisticians to engage with a methodology perceived to be too complex, and involving national accounting approaches they could not master. This “technically” driven choice had however substantial consequences on the public reception of the study. The applied method was less suited to address the purchasing power question, and thus was also far from adequate to address the societal demands for more accurate data on price differentials.

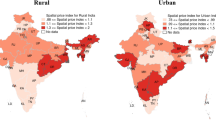

The study compared the value of a basket of representative consumer goods observed in the DOM to what exactly would be the price of this same basket in mainland France; conversely, it compared a typical mainland basket to what its price would be in the DOM; and then, in a last step, it determined an average.

The applied method can be considered problematic for a balanced understanding of the purchasing power issue for several reasons. For example, nobody drinks whisky in the West Indies, and conversely, few people in France eat yam. The comparisons outlined above fail to adequately consider such (cultural) differences between consumption patterns, and are in the end not very accurate with regard to reflecting people’s behaviours and preferences. In addition, the results are not very legible to the unversed: the final, synthetic gap indicator is computed with the help of a complex methodology (resulting in a geometric average, based on Fisher’s law), which is not easily understandable (see also Table 11.1).

A further factor complicated the public reception of the “spatial price comparison”. The synthetic indicator put forward by the statisticians in the study amounted to about fifteen percent, to be precise 14.8%. Estimating the price gap with mainland France at such a level could obviously create misunderstanding in Guadeloupe given that differences exceeding 50% had been so far mentioned in all studies that were based on the observation of supermarket shelf prices, in particular concerning many of the most common imported goods, such as food and household products. Representations of high living costs and pwofitasyon were thus based on estimated differences of 50% or more. The INSEE figure did not contradict these estimates, as it was based on a sample of different prices, including prices for which the difference was much smaller or even negative, such as rental prices, insurance premiums, etc., which explains the lower value of their indicator.

But the difference calculated by the INSEE was not socially acceptable, because it was not in line with the commonly shared representation of the “high level” of abuse existing on the island. Besides, claiming that there is a 15% price differential could also pave the way for a possible questioning of the 40% bonuses (the sur-rémunérations) granted to civil servants. We have seen before how politically sensitive these are. When INSEE’s study was published in the summer of 2010, the spatial price comparison failed to settle the debate. Instead, it led to the creation of more controversy.

Among other things, the publication of the study was undermined by an untimely intervention of the Prefecture. INSEE’s regional office had planned a press conference to accompany the release of the study in order to be able to publicly explain the results and guide interpretations to be attributed to the figures, to highlight what conclusions could (and could not) be drawn from the study. For example, they wanted to stress the considerably large increase of food prices and the disturbing growth of the synthetic gaps over the last ten years in this area—results which were in line with the movement’s expectations. Yet, before the press conference could take place, the regional INSEE office was put under pressure by the Prefecture and by Paris.32 The French Ministry in charge of overseas territories and the Prefecture did not want the results of the study to get any media coverage as the public release of the results coincided with the “unfreezing” of gasoline prices in July 2010. Thus the officials were worried that, in this context, INSEE’s study might inflame matters further.

This statistical work produced by the INSEE was thus one of the salient points in the end-of-conflict agreement, but its publication went completely unnoticed. It even spread dissent. In mid-August 2010, a controversy began to grow, opposing in particular the MEDEF, the Regional council and the INSEE. The interventions drew a connection between the price gap indicator of roughly 15% which INSEE had identified and the level of the civil servants’ over-remunerations, as if INSEE’s study was linked to an alleged plan to question the over-remunerations, which of course was not what had been intended (Bellance & Coste, 2010; DOM: le Medef remet en cause la sur-rémunération des fonctionnaires, newspaper article, Journal de l’ile de la Réunion, 11 August 2010; Drella, 2010; Sur-rémunérations, des avis plus contrastés à la Réunion, newspaper article, Journal de l’ile de la Réunion, 12 August 2010; Sur-rémunération des fonctionnaires: les clés du débat, newspaper article, France-Antilles Guadeloupe, 16 August 2010).

Victorin Lurel, President of the region at the time, even accused INSEE of publishing studies “on the sly” in order to call into question the social gains of past struggles. A multiplicity of reactions followed, some in favour of, some against a questioning of over-remunerations, by associations, parties, newspapers, etc. (Erichot, 2010). Thus, the synthetic 15% difference, although produced by expert statisticians, failed to be regarded as a legitimate numerical representation of the department’s high cost of living problems. Neither was it able to offer mediation in the social conflict.

INSEE’s work had not been vain, though. Victorin Lurel himself, who meanwhile had become a minister, used the study a few years later as one of the pillars in his communications. He nonetheless noticeably changed the interpretation of the results. This is how he presented his draft economic regulation law for the overseas territories to the Senate in 2013:

Inside these territories, the prices of most goods and services remain much higher than those of mainland France (a gap of 22% to 38.5% was measured by INSEE in 2010 on food products alone). Yet, at the same time, wages are notoriously lower there, with the median income below 38% [of that of mainland France], again in 2010 according to INSEE. (Lurel, 2012)

He thus uses the study as the cornerstone of a new strategy of communication on price levels. I will show in the following that this strategy succeeded in asserting itself by representing prices not through their average values or an average index,33 but particular, extreme values, considered to be a fairer representation of the inequitable situation lived by many Guadeloupians.

Towards a New Articulation of Prices and Margins

This last section will show how new legitimate quantifications of prices and margins emerged in the wake of the social conflict. These quantifications did not consist of synthetic price indicators. To the contrary, these new quantifications focused on the reporting and denunciation of individual price abuses. Their emergence becomes particularly clear in a series of studies and opinions which investigated the question of price abuses in the months after the struggle had been resolved.

The Competition Authority’s Report published in September 2009 (Autorité de la concurrence, 2009b) identified a long list of likely violations of competition law in the large-scale retail and import sectors. The report highlighted in particular suspicions of vertical anti-competitive integration. Importers representing certain brands appeared to own some of the main retail chains, opening the way to illegal exclusive arrangements, thereby blocking price competition. Likewise, agreements between local importers and mainland suppliers appeared to hinder new importers from entering the market, obliging the retail chains to deal with the brands’ local representatives.

The Competition Authority Report of 2009 further considered that the difficult access to real estate on the island could act as a barrier to entry, preventing new distributors from finding land to establish their business. Conversely, local actors and descendants of old land-owning families had an advantage. The Authority thus asserted in its communication from 8 September 2009 (Autorité de la concurrence, 2009b, 2009c):

In the DOM, the markets’ small size and their distance from the main supply sources are natural obstacles to obtaining prices comparable to those noted in mainland France. [...] However, these particularities do not suffice to explain the price gaps on large consumption items between mainland France and the DOM. Price data from a sample of around 75 imported goods collected in the four DOM show that differences exceed 55% for over 50% of the sampled goods, a percentage that is too high to be explained solely by freight costs and dock dues (“octroi de mer”). Above all, the Authority identifies several features of the supply chain in the DOM markets which enable the operators to partially escape the competitive game. (Autorité de la concurrence, 2009c)

These conclusions delighted LKP’s members, in particular the most leftist trade unionists. The report meant indeed that the official Authority in charge of the most liberal economic regulations acknowledged the relevance of their analyses of the Guadeloupian markets. This is how LKP’s main economist commented on the report:

This report is truly devastating for the large-scale retail sector and for the importers. It explains that pwofitasyon is very strong in this sector. It explains that prices exceed those of mainland France by an average of 20 to 60%; some of them even by up to 100%. We had already said so, but this time it is [officially] written, in contradiction with the statistics of INSEE—another public body—according to whom the price differential is a mere 10%. This time, thanks to our work, they are obliged to tell the truth about the prices and about the margins, which are sometimes up to 100%. […] These are centuries-old colonial ties. [...] A manufacturer can decide to grant exclusive rights to a company in Guadeloupe. [….] Thanks to these ties both parties make profits. [...] Such practices are illegal, and the report acknowledges it when it considers punishing anticompetitive practices. (UGTG, 2009)

LKP members thus saw the report as a legitimation vehicle of their own quantification methods aimed at attesting the existence of pwofitasyon.

Before the Competition Authority’s report had been published, a fact-finding mission dispatched by the Senate during the movement had led to the publication of another report in July 2009 (Doligé, 2009). In a long passage titled “The crucial question of prices: A two-way solution, competition and, above all transparency” (Doligé, 2009, pp. 118–149), the report calls for a clear analysis of price formation, to reveal the specific cost items entailing high prices. It regrets that state services had not managed to ensure price surveillance, neither INSEE nor DGCCRF. In addition, the report supports the idea of the existence of predatory pricing (Doligé, 2009, pp. 121–123). To prove the existence of such pricing practices, it presents a large amount of information on individual prices and economic operators.

Regarding freight, for example, it denounces the monopoly held by the French sea-freight giant CMA-CGM, as well as the excessive prices it imposes on the market. To prove its assertions, it compares and contrasts cost figures presented by the Organization of French ship-owners with other expert estimates. Its conclusions are definitive: the data provided by the operators are shown to be false, and the report accuses the shipping companies of being responsible for 5–15% of the final retail price of large consumption goods (Doligé, 2009, pp. 141–143). In the same vein, the report accuses Air France of charging too high tariffs, by comparing them to other airlines’ tariffs. It also presents the oligopolistic structure of large-scale retail by showing in a table which supermarket chain belongs to which old family, thereby highlighting the inherited dominant positions of the economic elites (Doligé, 2009, pp. 127, 129). In other words, the Senate’s fact-finding mission took on the role of an informer, adopting a “naming and shaming” logic in its presentation of price data. It adopted its own methods to deal with the problem of price levels. In doing so, it legitimized the movement’s position, and it endorsed LKP’s inferences.

The price surveys carried out by the mission highlighted that price differences seemed totally random, thus excluding the possibility of explaining them by systematic factors, such as increased supply costs. In addition, the mission took account of individual cases to expose price differentials, including minute details as the following (see also Table 11.2):

The price of ‘Nesquik’, an imported product, is considerably higher in the DOM: 42% in La Réunion, 75% in Martinique (although the product was on special offer there), 128% in Guadeloupe and 142% in Guyana. (Doligé, 2009, p. 126)

Thus, the report turned each price, as experienced by the consumers in their everyday life, into an indication of the existence of abuse and injustice, deserving to be discussed and publicly denounced in an official document. Shortly before, price aggregates had been deemed liable for the triggering of strong protests, and at least some considered it better not to discuss those in public. But in 2009, it appeared that individual prices could be considered meaningful events (Boltanski & Esquerre, 2017) proving the existence of unacceptable practices, and deserved to be known by the public.

Many other instances of this way of quantifying and debating prices and price differentials can be found after the 2009 conflict: for instance, in press articles (Vachert, 2010), in studies by consumer associations,34 in surveys carried out by the LKP feeding the press (Témoignage, 2010), etc., which suggests a real change in how prices and price differentials were considered and quantified. This change is also confirmed by an episode that stayed in everyone’s memory, because it caused hilarity on the island: Yves Jégo, shortly after his arrival in Guadeloupe, was shocked and started protesting against the “4 Euro toothbrushes”. Jégo, then a minister of Overseas territories, suggested several concrete measures to fight such abuses: in addition to a surveillance unit, it was planned that a toll-free number would be installed for the receipt of instant complaints from consumers noting abusive prices in supermarkets. In this, his plans echoed LKP’s very Trotskyist proposal to create “price brigades” charged with the enforcement of the agreements, which the collective had submitted to the Prefect in the aftermath of the conflict.

Against this background, it becomes clearer why INSEE’s synthetic price index, which was based on the calculation of averages for the entire economy, was considered indistinct at the time, as it was not limited to certain symbolically significant basic items (such as toothbrushes) in an attempt to avoid any overstatement (Témoignage, 2010). Since then, we can observe a shift in the representations of price gaps which the mainland considered legitimate. Moral criteria were increasingly used to talk about price levels, and the denunciation of individually high prices seen as “abusive” became widely acceptable. In this context, magnitudes had to be sufficiently high to be deemed acceptable and fit understandings of unjust price differentials; for instance, “several tens” appeared to be in line with representations of levels of abuse; and measurement was supposed to get closer to control such abuses (i.e. prices came to be seen as something that must be controlled, audited and possibly denounced and acted upon).

Victorin Lurel, for example, as already shown above, used the INSEE study several years after its publication, when he presented his draft law for overseas economic regulation to the Senate. Here’s what the Minister declared, following the passage cited above:

[…] we are not talking about relatively bearable differences of 10, 15 or even 20%. No, we are talking about the chocolate powder all families in mainland France and overseas put on their breakfast table, which can be found at € 3.10 here in Paris, while it may be priced € 4.40 in La Réunion, € 5.43 in Martinique, € 7.08 in Guadeloupe, and even € 7.50 in Guyana!

We are talking about four pots of plain yogurt, priced at € 1.15 in mainland France, and never less than € 2.30 overseas. Here again, a 100% difference for two identical everyday goods.

I could continue the list of examples, which may seem harmless and trivial to you. But believe me, Ladies and Gentlemen of the Senate, they are the testimony of the striking injustice our overseas fellow-citizens feel and which can become a ferment for a feeling of abandonment. (Lurel, 2012)

Victorin Lurel clearly and explicitly expressed this new legitimate way of articulating the price question. The draft law he then presented focused on avoiding “inadmissible” practices: it affirmed the right to regulate basic product prices, trade margins and to sanction abusive practices by using a new tool, the “power of structural injunction” (Evrard, 2013). According to this legislation, a firm appearing to have built a dominant position on a given market could be forced to cede a part of its productive capital (land, shops, machines) in order to make the market more competitive (Venayre, 2015).

Conclusion

This chapter has studied the role of the measurement of prices and commercial margins in the 2009 Guadeloupian social struggle against high living costs. It first showed that calculation was central in the framing of the mobilization (Cefaï & Trom, 2001). The State and some leading economic actors (in particular large-scale retail and oil industry operators) used quantitative tools to manage or regulate prices. These practices triggered revolt on the island, because they were considered opaque and illegitimate by several political parties, unions and other associations. The actors who led the strike, grouped in the LKP collective, used their own quantification and economic analysis techniques to identify abusive pricing and margin-setting mechanisms, and to prove that pricing practices on the Island had enabled wealth extraction from Guadeloupian consumers—a situation they referred to as pwofitasyon.

Calculation was also central throughout the struggle and in the ensuing negotiations. This chapter described thus a “statactivist” (Bruno et al., 2014) movement in action, showing that the use of quantification was one of the best political weapons employed by the LKP collective. The LKP succeeded in challenging the State and powerful economic actors on their own ground by using quantified arguments. It showed that it was possible to use economic numbers and arguments to get existing policies shifting. INSEE attempted to play a mediating role in these negotiations.

However, at the same time, the chapter also showed that quantification and calculation can end up being one’s Achilles heel—in this case LKP’s. Although some members of the LKP were highly informed economic experts, in the end, it was not possible for them to compete with the State’s calculative skills and expertise on an equal basis, and their pertinent use of numbers could only establish temporarily a favourable balance of power in the negotiations. This observation is important at a time when prices are measured through ever more complex statistical techniques. The possibilities to use quantification as an emancipatory device could be shrinking with the greater complexity of statistical tools (Jany-Catrice, 2019; Touchelay, 2014). By making such a point, and by documenting the use of numbers by trade unions, this chapter fills a gap in the literature on quantification and on “statactivism”.

Finally, the chapter stressed the existence of multiple price level measurement methods, and the shifting legitimacies associated with each of them in the post-2009 Guadeloupian society. It showed that, although scientifically legitimate, INSEE’s price indexes were subject to radical political criticism by a range of actors. By using an average, these indexes could indeed not account for the existence of the abusive prices that were targeted by LKP’s mobilization. The high level of prices on some widely used consumption items was indeed considered as a form of political oppression, and INSEE’s publications nurtured controversies by not singling them out: LKP actors, the press and Guadeloupian officials accused the statistical office of making the existence of such price abuses invisible.

Furthermore, the aggregate indexes displayed a price difference between Guadeloupe and mainland France of 10–15%, a magnitude that was widely perceived as contradicting the everyday experience of consumers, who, at least in some instances, experienced price gaps of 100% and more. The perceived illegitimacy of INSEE’s numbers shows that there existed a different, generally accepted and naturalized, understanding of value in the Guadeloupian society at the time, based on consumers’ experiences and on their imagination of what the price gap had been (in this case around 40% at least, also corresponding to the historical sur-rémunerations entitled to the civil servants in Guadeloupe).