Abstract

This chapter introduces the topic of social exclusion in later life and presents a rationale for this edited volume. It will provide an overview of existing knowledge, focusing specifically on research deficits and the implications of these deficits for scientific study in the area, and for effective and implemental policy development. This chapter will outline the aim and objectives of the book in response to these deficits and will outline the book’s structure and the critical approach that is adopted for the volume, and that is rooted in state-of-the-art conceptual knowledge.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

This book examines social exclusion in later life, its key attributes and manifestations, and its construction and amelioration through policy structures and systems. The significance of demographic ageing, inequalities amongst older populations, and rising economic, social and political uncertainty, is clear for many advanced industrial societies. So too is the potential for these trends and processes to intersect and reinforce each other (Nazroo 2017; Hargittai et al. 2019; Dahlberg et al. 2020). Despite these circumstances suggesting the need for a strong focus on the exclusion of older people, research and policy debates on this topic have stagnated in recent years. This has contributed to the absence of a coherent research agenda on old-age social exclusion, and a lack of conceptual and theoretical development (Van Regenmortel et al. 2016; Walsh et al. 2017). It has also meant that innovative policy responses, that are effective in reducing exclusion for older people, are in relatively short supply (ROSEnet 2020).

As a societal issue in a globalised world, it can be argued that social exclusion in later life has become more complex in its construction, and potentially more pervasive in its implications for individual lives and for societies. There is now a growing evidence base that points to how it can implicate interconnected economic, social, service, civic (civic participation and socio-cultural), and community and spatial domains of daily life (Dahlberg et al. 2020; Prattley et al. 2020). Understanding social exclusion of older people is, however, not just about a focus on older-age and the way that age-related changes, and a society’s response to those changes, can give rise to exclusionary mechanisms. It is also about providing insight into processes of risk accumulation across the life course, identifying crucial points for early intervention, and highlighting the degree of impact when earlier forms of exclusion go unaddressed (Grenier et al. 2020).

Against this background, there is a pressing need to address stagnated debates on social exclusion in later life, and the deficits in research and policy that they sustain. These circumstances have become more urgent in the wake of the outbreak of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This edited volume responds to this need.

2 Rationale – Stagnated Policy and Research

The lack of advances in research and policy may, in part, be due to a number of political factors that betray a research-policy misalignment.

First, is the traditional absence of ageing from social equality agendas (Warburton et al. 2013). In many jurisdictions, ageing remains entrenched within a health framing and, although social protection portfolios pursue goals around pension adequacy and sustainability, it appears largely to be considered the domain of health policy. Second, demographic ageing is more likely to be seen as a threat to the sustainability and effectiveness of social inclusion orientated structures (i.e. institutions; policies), than a focus of those structures (Phillipson 2020). This is both at the level of national states and within European political forums, where there can be a problematisation of demographic ageing in relation to maintaining social protection systems. Third, more entrenched, and sometimes subtle, ageist discourses negatively locate older people within our societies. As such, there can be a systemic political complacency towards the concerns of ageing populations, or even a more active discriminatory marginalisation of their needs and position (Ayalon and Tesch-Römer 2017). It can certainly be argued that the COVID-19 pandemic has only served to intensify each of these three factors.

Fourth, and perhaps most significant of all, there are questions around whether or not social exclusion of older people is a critical public policy issue, with debates around the extent to which older adults are experiencing exclusion. Within Europe, the European Commission’s ‘At-Risk of Poverty and Social Exclusion’ (AROPE) measure suggests a need to focus on children (of whom 26.9% are identified as being at risk of poverty and social exclusion), single parents (50%) and particularly the unemployed (66.6%). People aged 65 years and over appear to be less at risk (18.1%) (Eurostat 2019), with policymakers unlikely to be as motivated to drive innovation to address social exclusion in later life. However, the AROPE measure focuses on economic forms of disadvantage concentrating on those at-risk of poverty, or those experiencing severe material deprivation, or those households with low work intensity. This is in contrast to the significant body of empirical research that illustrates the need to broaden our thinking about exclusion in older-age, and how older people may simultaneously be susceptible to multiple and interconnected forms of disadvantage (Kendig and Nazroo 2016; Dahlberg and McKee 2018; Macleod et al. 2019). The AROPE measure, therefore, is likely to fall short in capturing complex, multidimensional exclusion.

Stagnated debates are also likely to be due to conceptual factors, and the awkwardness of the social exclusion concept. Although the comprehensiveness of the construct is credited with providing valuable insights into multidimensional disadvantage for older people, there is a difficulty in empirically and conceptually representing that comprehensiveness (Van Regenmortel et al. 2016). Common critiques focus on the concept’s failure to foster an analytical frame that supports theoretical elaboration and the development of actionable policies (Bradshaw 2004). This fundamentally undermines the establishment of large-scale research programmes, and meaningful policy and practice implementation plans. As a result, much of our knowledge continues to reside in single domain fields, such as services or social relations, with a failure to adequately account for the interrelationships across domains (Walsh et al. 2017). Additionally, even though there is recognition that exclusion in later life involves both individual and societal/policy levels, most existing work continues to neglect multilevel analyses – again, functioning to impede effective progress in research and policy. Therefore, from a research perspective, how to account for disadvantages in different domains of life, while exploring their interrelated and multilevel construction, is a fundamental challenge.

Like other complex social phenomena, social exclusion in later life is relative. Just as with multidimensionality (Atkinson 1998), this represents both a valuable conceptual attribute and a challenge that impedes the development of frameworks for researching and reducing exclusion in different jurisdictions. For ageing societies, there are four parameters that can influence the construction and meaning of exclusion in later life (Scharf and Keating 2012; Macleod et al. 2019). First, there are different patterns of demographic ageing, with heterogeneity (related to ethnicity, sexual orientation, class and expectations around rights) across and within older populations. Second, there are different degrees of age-related institutional infrastructure, underpinned by diverse value systems. Third, there are distinct sets of cohort experiences linked to context-specific cultural, socio-economic and geo-political forces (e.g. conflict; recession; immigration). And fourth, there are country/region specific scientific paradigms that influence views on disadvantage in older-age and that remain outside the English-language literature (Walsh et al. 2017). Addressing and harnessing the relative nature of older adult exclusion is essential if we want to pursue meaningful cross-national comparisons. It is also essential if we want to design policy responses that are appropriate both within and across nations.

Aside from political and conceptual factors, it is also necessary to consider our capacity to advance the agenda on social exclusion of older people. International research has a long-standing engagement with the construction of inequalities for older adults, driven by a commitment to critical perspectives in gerontology. While this scholarship has expanded our understanding of disadvantage in later life, it has in relative terms not been as influential in progressing debates on older adult exclusion as might have been expected. Instead, a more applied approach has dominated, which has typically been more descriptive. Secondly, research capacity on this topic has been underdeveloped and undermines our ability to critically analyse the topic of old-age social exclusion into the future. As a result, questions persist about how we engage a new audience of early-stage researchers and policy analysts in these debates. There is a need to create collaborative initiatives that will foster engagement opportunities for some and illustrate the value of such opportunities for others.

3 Aim and Objectives

Drawing on interdisciplinary, cross-national perspectives, this book aims to advance research and policy debates on social exclusion of older people by presenting state-of-the-art knowledge in relation to scholarship and policy challenges. In doing so, it seeks to develop a forward-looking research agenda on the multilevel, multidimensional and relative construction of social exclusion in later life.

The book has four key objectives:

-

1.

To produce a comprehensive analysis of social exclusion of older people, deconstructing its multidimensionality across different life domains, the interrelationship between these domains, and the involvement of individual and societal/policy levels.

-

2.

To present cross-national and interdisciplinary perspectives on social exclusion of older adults so as to account for the relative nature of exclusion and establish shared understandings of its meaning and construction.

-

3.

To institute a dialogue between conceptual and empirical perspectives, in order to strengthen the critical potential of empirical studies, and the empirical application of critical concepts.

-

4.

To nurture research capacity in the field of social exclusion and ageing, establishing meaningful collaborations between early-stage researchers and senior scholars across countries.

This book has emerged from a cross-national, and collaborative networking platform that focuses on Reducing Old-Age Social Exclusion – ROSEnet (COST Action CA15122). Involving established and early-career researchers, policy stakeholders and older people, ROSEnet comprises 180 members from 41 countries. ROSEnet aims to overcome fragmentation and critical gaps in conceptual innovation on old-age exclusion across the life course, in order to address the research-policy disconnect and tackle social exclusion amongst older people. ROSEnet is dedicated to developing shared understandings of old-age exclusion that are underpinned by state-of-the-art research and innovation, and that help to direct meaningful policy and practice development. The network involves five working groups that address different domains of exclusion (economic; social; service; civic; and community and spatial) and a programme of activities around domain interrelationships, and policy. ROSEnet, therefore, provides a strong foundation for addressing challenges around the comprehensive and relative nature of exclusion of older people.

In the remainder of this chapter, we will set out the central tenets of old-age exclusion and how they inform the book’s approach and structure. We begin by drawing on the findings of two recent reviews of the international literature (Van Regenmortel et al. 2016; Walsh et al. 2017) to conceptualise and define social exclusion in later life. We then consider the political evolution of social exclusion as a policy concept and the ways in which exclusion can be mediated by policy discourses. We conclude by outlining the book’s structure and approach.

4 Conceptualising and Defining Social Exclusion of Older People

There have been relatively few attempts to define social exclusion in later life, or indeed to conceptualise its construction (Van Regenmortel et al. 2016). While this reflects the paucity of scientific research on the topic, it also reflects the longstanding ambiguities concerning the general concept itself (Levitas et al. 2007).

Definitions of social exclusion have though typically engaged with what Atkinson (1998) identifies as a set of common characteristics of the construct. These features enhance the concept’s power to explain multifaceted and complex forms of disadvantage, but they also pose inherent challenges for the identification and assessment of the phenomenon. They include the conceptual attributes of multidimensionality (where older people can be excluded across multiple domains of life, or can be excluded in one domain and not in others) and that of its relative nature (where exclusion is relative to specific populations, institutions, values and a normative level of integration within a particular society) – which are the prime consideration of this volume. But they also include two other aspects of the construct. Social exclusion is dynamic, where older people can drift in and out of exclusion, and experience different forms of exclusion at different points of the life course. Social exclusion also involves agency or the act of exclusion, where older people, for instance, can be excluded against their will, may lack the capacity and resources for self-integration, and, whether consciously or sub-consciously, may choose to exclude themselves in certain situations.

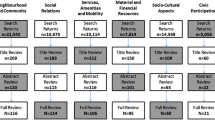

While there is renewed interest in conceptualising exclusion of older people, there has been a noticeable lack of innovation in theorising the intersection between ageing and exclusion. Adapted from Walsh et al. (2017), Table 1.1 reveals a small number of frameworks that attempt to explain old-age exclusion. Although these frameworks vary in their conceptual depth, common to all is the capacity of social exclusion to detract from a full model of participation (Van Regenmortel et al. 2016). In this regard, each conceptualisation attempts to unpack the multidimensionality of the exclusion construct in older-age across a set of domains. There is also a recognition that interrelationships are likely to exist between different forms of exclusion where outcomes in one domain may contribute to broader processes that result in outcomes in other domains [see Dahlberg, and section VII in this volume for a full exploration of these interrelationships]. While the relative nature of exclusion is not explicitly articulated, it is implied. Some frameworks are grounded in specific settings (e.g. rural Ireland/Northern Ireland – Walsh et al. 2012/2019), while others note the capacity of macro contexts (institutions, norms, values) in shaping exclusionary experiences (e.g. Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman 2008).

For the most part, an in-depth theoretical elaboration of how ageing and exclusionary processes intersect is largely neglected in these frameworks, with less of a focus on identifying the drivers of multidimensional exclusion. There are, however, a number of exceptions to this. Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman (2008) highlight the influence of macro risks surrounding social processes (e.g. population ageing; individualisation) and government policy/provision (e.g. inadequate policy), meso risks relating to official bodies, business and citizens (e.g. discrimination; inadequate implementation), and micro risks at the individual/household level (e.g. health). Walsh et al. (2012/2019) describe the influence of individual capacities, life-course trajectories, place characteristics, and macro-economic forces in mediating multilevel rural age-related exclusion. Finally, Macleod et al. (2019) identify economic factors, environment and neighbourhood, and health and well-being as key determinants of social exclusion in later life.

It is also worth noting that while not presenting formal conceptualisations, important edited volumes on social exclusion of older people (e.g. Scharf and Keating 2012; Börsch-Supan et al. 2015), seminal works on related concepts (such as cumulative advantage/disadvantage – Dannefer (2003); precarity – Grenier et al. (2020)), and recent empirical/measurement papers (Dahlberg and McKee 2018; Feng et al. 2018; Van Regenmortel et al. 2018; Prattley et al. 2020; Keogh et al. 2021) have significantly expanded our conceptual understanding of multifaceted forms of disadvantage in later life.

With reference to Fig. 1.1, Walsh et al. (2017) broadly summarise the conceptual structures of the different frameworks into six key domains of exclusion, and identify a series of domain sub dimensions (which represent processes and outcomes) from a review of 425 publications. Together with Scharf and Keating (2012), they also highlight three elements of old-age exclusion arising from this review. First, exclusion can be accumulated over the course of older people’s lives, contributing to an increased prevalence into older-age (e.g. Kneale 2012). Second, older people may have fewer opportunities and pathways to lift themselves out of exclusion (e.g. Scharf 2015). Third, older people may be more susceptible to exclusionary processes in their lives. This reflects the altered positioning of older adults with time, and specifically the potential to encounter ageism and age-based discrimination; age-related health declines; contracting social and support networks; and depleted income generation opportunities (Jehoel-Gijsbers and Vrooman 2008).

Old-age exclusion framework depicting interconnected domains and sub dimensionsSource: Walsh et al. 2017

We can now turn to the task of defining social exclusion amongst older people. A number of contributions within this volume present slightly different views of what exclusion in later life is. This is necessary to illustrate the variety of different perspectives, and to allow for more domain-specific mechanisms to be described. However, in order to set out the broad parameters of our focus – the same parameters that provided a conceptual scope for the ROSEnet COST Action – we adopt the following definition:

‘Old-age exclusion involves interchanges between multilevel risk factors, processes and outcomes. Varying in form and degree across the older adult life course, its complexity, impact and prevalence are amplified by old-age vulnerabilities, accumulated disadvantage for some groups, and constrained opportunities to ameliorate exclusion. Old-age exclusion leads to inequities in choice and control, resources and relationships, and power and rights in key domains of neighbourhood and community; services, amenities and mobility; material and financial resources; social relations; socio-cultural aspects of society; and civic participation. Old-age exclusion implicates states, societies, communities and individuals’.

Therefore, and as highlighted within this definition, old-age social exclusion is a life-course construction that is influenced and shaped by individual, group and institutional factors encountered across the life course, and not just those specific to the stage of old-age.

As reflected in the work of the ROSEnet Action, and its organisation around its five working groups, in this volume we condense the domains of exclusion into: economic; social relations; services; community and spatial; and civic, where the latter is an amalgamation of exclusion from civic participation and socio-cultural aspects of exclusion.

5 Social Exclusion, Policy and COVID-19

Defining exclusion in this manner, and acknowledging its various conceptual attributes, is essential for a volume committed to presenting and advancing state-of-the-art scientific research. However, focusing solely on scholarly perspectives neglects how these traditions are intertwined with the construct’s lineage within policy/political discourse.

Although French sociology is credited with elaborating the core semantic meaning of social exclusion, the concept first appeared in the social policy analysis of Rene Lenoir in the 1970s, the then Secretary for State on Social Action in France. Building upon French republican ideologies, Lenoir’s (1974) book Les Exclus identified a two-tier society where certain population groups were disconnected from, and unprotected by, core societal institutions. Although originally concentrating on manifestations of structural unemployment, social exclusion began to evolve as a broader descriptor of social disadvantage that was associated with new forms of urban poverty during the 1970s and 1980s. Social exclusion became ‘institutionalised’ in French public policy in the early 1990s when it was defined as a rupture in the social fabric, and a deficiency in solidarity (Mathieson et al. 2008; Silver 2019).

The concept was also adopted and developed as a core focus of social policy within other contexts around the same period – sometimes drawing on the evolving French political discourse, and sometimes harnessing other policy traditions (Mathieson et al. 2008). As described by Silver (2019), social exclusion and poverty became tied as core policy concerns within Europe’s social agenda when a commitment to combating social exclusion was made in 1989. By 2001, European member states had agreed to report on progress on a set of social indicators within National Action Plans for Social Inclusion (later termed National Social Reports), and the commitment to tackle social exclusion remains evident within contemporary European policy frameworks. In the UK, the 1997 New Labour Government embraced the multidimensionality of exclusion to underpin a joined-up approach for tackling complex multifaceted social problems (Mathieson et al. 2008). This built upon longstanding critical social policy interests in the study of structural inequalities and power imbalances that construct a ‘moral underclass’ (Townsend, 1979). But social exclusion is also evident within the social policy agendas of international settings such as in North America, Australasia, and Asia (Warburton et al. 2013).

While the concept has altered in meaning over the years, and has at times been used interchangeably with social inclusion, it has once again come to espouse a focus on economic disadvantage within many jurisdictions. Labour market participation thus represents the main mechanism to combat exclusion, and a lack of attachment to the labour market its ultimate example (European Commission 2011). This gives rise to an uncomfortable tension with respect to how to reduce exclusion in later life, and the relevance of such measures.

Consequently, the fates of research and policy discourse need to be considered intertwined if advancement in the field is truly sought. It is for this reason that ROSEnet has attempted to produce shared understandings of old-age exclusion across research and policy communities. This has been as much to benefit from the intersectoral knowledge of policy actors, as to foster research-informed policy development. However, it has also been to illuminate the role of policy in mediating late-life exclusionary experiences. Narrow formulations of ageing within public policy can reinforce notions of homogeneity, propagate ageism and strip back complex identities of older populations to single age-related dimensions and associations (Biggs and Kimberley 2013; North and Fiske 2013). Even when policy is more comprehensive in its approach, a lack of implementation and resource allocation has often plagued the ageing sector. But clearly, policy can also have a substantial role to play in promoting fairness and inclusivity for older adults, protecting against exclusion. There are now a number of policy frameworks and initiatives that have considerable potential to enrich the lives of older people. This includes the EU Pillar for Social Rights, the United Nation’s (UN) Sustainable Development Goals [both of which are considered within this volume], and the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Age-Friendly Environments programme and the Decade of Healthy Ageing (2020–2030).

Ultimately, the dynamic nature of public policy environments, and older peoples’ lives, demands that the impact of policies are continuously evaluated. The COVID-19 pandemic marks a recent and a significant global example of the need to attend to the multilevel interplay between policy and exclusionary experiences in older-age. We are writing this chapter in the midst of the global pandemic, with an ever growing number of cases and deaths announced each day across Europe and internationally. It is apparent that the impact of this traumatic crisis will live long in our global collective memory. It is also apparent that it is likely to be etched across many core aspects of our societies, including our public health policies, economies and, very possibly, demographic age structures with a disproportionate, and an alarming, number of deaths in older-age groups. Notwithstanding the significant risk to the health of older individuals (particularly those resident in nursing homes), and the immediate consequences of the virus for well-being, there has been a clear emergence of exclusionary mechanisms for older people associated with policy responses during the pandemic.

First, there are those mechanisms that stem directly from the strategies employed to control the spread of COVID-19, which produce exclusions in older people’s daily lives (Le Couteur et al. 2020). These include: profound forms of digital exclusion, where some older adults may struggle to access critical online health information; barriers to attending essential medical appointments for the fear of contracting the virus or stigmatisation related to health service use during the pandemic; and the, well-publicised, increased risk of loneliness, and lack of support, due to self-isolation and “cocooning” (Brooke and Jackson 2020). Many of these exclusions are only intensified for older people living in nursing homes, where access to external social connections, services and other formal and informal supports is likely to be greatly diminished.

Second, there are direct exclusionary processes and outcomes that may arise from decision-making practices, informal or otherwise, that are integral to COVID-19 treatment pathways. Evidence suggested, that in some jurisdictions, the shortage of intensive care unit beds and ventilators led to the prioritisation of younger, healthier patients with a higher chance of recovery in treatment centres. While these circumstances place considerable moral strain and ethical responsibility on front-line health professionals, they also side-line need as a basis for resource allocation and exacerbate the risk of poorer outcomes for older individuals.

Third, public and policy discourses on ageing and older people have the potential to act as powerful exclusionary and discriminatory processes. This has emerged across two dimensions. While not many would argue with what appears to be a strong sentiment of concern, the paternalistic nature of protectionist endeavours, such as cocooning, have functioned to homogenise older people as highly vulnerable, passive agents in the pandemic (AGE Platform 2020). This has superseded the massive diversity of needs across older populations, and undermined the informal practices engaged in by older people that are emerging in response to the outbreak. More critically, however, there has been evidence of a problematisation of ageing in the context of the pandemic, where older people have been framed in some sections of the public sphere as en masse consumers of valuable and limited resources, blocking the access of younger, healthier individuals to treatment services. This has given rise to questions about the need to re-evaluate the social contract in favour of people who are deemed to be more “productive”, and more tangibly contributing to the development, sustainability and economic welfare of societies (United Nations 2020). Aside from serving as a destabilising threat to solidarity across the generations, such discourses function to devalue not only the status of older people as equal citizens, but the value that we place on their contributions, and their lives, in our society. If such discourses are operational at a policy and practice level, then “cocooning” could be viewed in a very different light, where it is less about protecting people in older-age and more about protecting the health system and its resources for younger cohorts. This is, of course, played out at the level of our formal care settings, our communities, and to a degree within our own homes, and may have very real consequences for resource allocation and health outcomes.

The treatment of nursing homes and nursing home residents in many western nations during the pandemic has epitomised the most severe form of this problematisation. Indeed, it may have exposed a more systemic collective ease at the segregation of these facilities, and the health vulnerabilities of their older populations, away from mainstream society. The fact that many countries failed to count COVID-related deaths in nursing homes can be argued to be the ultimate exclusion, stripping individual identities and devaluing individual lives.

While the chapters in this book will not engage directly with this topic, having been written primarily before the onset of the pandemic, they have a strong relevance to the COVID-19 crisis and a capacity to illustrate why exclusion is occurring as a result of the outbreak. On a more general level, these dynamics draw attention to how significant shocks, be they from public health, environmental, or economic sources (e.g. Adams et al. 2011), can quickly alter the social, economic and symbolic circumstances of older people with short-, medium- and long-term consequences for ageing societies.

6 Approach and Structure of This Book

Current conceptualisations of social exclusion in later life, in terms of its multidimensional and relative nature, and its relevance and relationship to policy, has directly informed the approach and structure of this book. This edited volume involves 77 contributors working across 28 nations, and comprises 34 chapters. Twenty-four chapters are co-authored by cross-national interdisciplinary writing teams, fostering sensitivity to relative differences in jurisdictional circumstances, and integrating diverse understandings, literatures and empirical data from national settings that are not typically featured in English-language volumes. Twenty-four chapters also represent writing partnerships between early-career researchers and established international experts at the forefront of academic scholarship, with approximately 40 early-career researchers contributing to the volume.

Across this volume, contributors have been encouraged to adopt a life-course and critical gerontological understanding of social exclusion in later life. While direct engagement with these perspectives is certainly evident in some chapters more than others, authors generally are cognizant within their analysis of earlier life events, changes over time, turning points and transitions, the influence of structural and institutional factors, and the positionality of ageing and older people within cultural and normative value systems. A number of contributions also directly address the intersectionality of key social locations, ageing and exclusion, and/or the position of marginalised sections of the older population. This includes gender, ethic and migration background, socio-economic status and class, dementia, and homelessness.

The book is divided into eight sections, with the main body organised in accordance with the multidimensional structure of social exclusion in later life, and policy related challenges.

Sections II–VI will consider the five domains of old-age social exclusion: economic; social relations; services; community and spatial; and civic exclusion. Each section comprises four chapters. A short introductory chapter, written by co-leaders of the relevant ROSEnet working groups, will introduce the exclusion domain. It will also frame the subsequent three chapters, with each of these exploring a different sub dimension of the exclusion domain.

Section II focuses on economic exclusion. Jim Ogg and Michal Myck introduce economic aspects of exclusion in later life in Chap. 2. The authors emphasise the need to consider its many dimensions from a life-course perspective. As such, they highlight the importance of exploring multidimensional economic outcomes in older-age as a product of the combination of all life stages. In Chap. 3, Sumil-Laanemaa et al. assess the variation in material deprivation of the population aged 50+ across four geographic clusters of welfare regimes in Europe. Murdock et al., in Chap. 4, explore job loss in older-age, as a form of acute economic exclusion, and its implications for mental health in later life. Barlin et al., in Chap. 5, chart the economic exclusion and coping mechanisms of widowed, and divorced and separated older women in Turkey and Serbia.

Section III focuses on exclusion from social relations. In Chap. 6, Vanessa Burholt and Marja Aartsen introduce exclusion from social relations in later life. In addition to highlighting risk factors and the dynamic nature of exclusion from social relations, Burholt and Aartsen emphasise the impact of psychological resources, socio-economic processes and immediate neighbourhood environments on the exclusion process. In Chap. 7, Van Regenmortel et al. analyse the manifestations and drivers of exclusion from social relations, in Belgium and rural Britain, and consider links with other forms of disadvantage. In Chap. 8, Morgan et al. examine the impact of micro- and macro-level drivers of loneliness and changes in the experiences of loneliness in eleven European countries. In Chap. 9, Waldegrave et al. explore the complex nature of the conflicted, abusive and discriminative relations of older people and their differential impacts across countries.

Section IV focuses on exclusion from services. Veerle Draulans and Giovanni Lamura introduce exclusion from services in Chap. 10. The authors highlight the need to consider particular macro- and micro-level factors in the construction of exclusion from services, with the focus on the former relating to the increasing individualisation of risk, and the latter on the intersection of age and other social locations. In Chap. 11, Cholat and Daconto explore how reverse mobilities, where services travel to service users, may promote older people’s inclusion in mountain areas. Széman et al. in Chap. 12, investigate patterns and construction of exclusion from home care services in Central and Eastern European countries, focusing on Hungary and Russia. Finally, in Chap. 13, Poli et al. examine the provision of care and support through digital health technologies, and present a conceptual framework for old-age digital health exclusion.

Section V focuses on community and spatial aspects of exclusion. In Chap. 14, Isabelle Tournier and Lucie Vidovićová introduce this form of exclusion and explore the notion of a “good place”. Drawing on a model of life space, they emphasise the intersection of multilevel spatial environments and the needs of older adults with respect to engagement and inclusion. In Chap. 15, Drilling et al. present a theoretical model that integrates the dimensions of age, space and exclusion in one perspective, and explores its potential to explain older people’s exclusion. Urbaniak et al., in Chap. 16, investigate how relationships with place and old-age social exclusion intersect during the life-course transitions of bereavement and retirement. In Chap. 17, Vidovićová et al. explore how exclusion from care provision in rural areas can be understood as a form of place-based disadvantage in three central European countries.

Section VI focuses on civic exclusion. Sandra Torres introduces civic exclusion in later life in Chap. 18. Torres provides an overview of existing understandings of both exclusion from civic participation and socio-cultural aspects of exclusion and outlines the importance of considering the heterogeneity of older populations and their life-course experiences within this topic. In Chap. 19, Serrat et al. present an analysis of older people’s exclusion from civic engagement, and emphasise the importance of considering its multidimensionality, and its cultural embeddedness. Gallistl, in Chap. 20, examines patterns of cultural participation for older people, drawing out the relationship of changes in these patterns with socio-economic status. Finally, in Chap. 21, Gallassi and Harrysson situate ageing and migration within the setting of international human rights law and how the principles of equality and non-discrimination can help combat exclusions for ageing migrants.

Section VII specifically explores the interrelationships between the exclusion domains. Illuminating ways in which different processes of exclusion can intersect, this section is pivotal in developing an understanding of old-age exclusion that goes beyond a collection of single domains. In the first of five chapters, Lena Dahlberg, in Chap. 22, introduces the study of interrelationships as developed in the international literature. Dahlberg charts the interconnections that have been identified across the domains before highlighting key knowledge gaps and outlining each of the remaining contributions. In Chap. 23, Villar et al. examines the circumstances of older people in long-term care institutions and the potential for exclusion from social relationships, civic participation and socio-cultural life. In Chap. 24, Myck et al. assess the relationship between material conditions and the level and dynamics of loneliness in later life. Siren, in Chap. 25, employs the concept of “structural lag” to analyse the links between transport mobility, well-being and wider constructions of multidimensional exclusion. In the final contribution, Korkmaz-Yaylagul and Bas in Chap. 26 explore the multidimensional aspects of old-age exclusion in the homelessness literature, and how homelessness can be a significant determinant of interrelated sets of disadvantages.

Section VIII is specifically dedicated to policy challenges in relation to social exclusion in later life. Comprising of an introduction and six chapters, the majority of authors are drawn from policy stakeholder organisations. In Chap. 27, Norah Keating and Maria Cheshire-Allen introduce social exclusion as a policy framework for population ageing and older persons. They highlight how values, political agendas and competition among multiple social goals require as much attention as scientific evidence in assessing current policy debates. Conboy, in Chap. 28, explores the potential of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development to serve as a global framework for addressing multidimensional old-age exclusion. In Chap. 29, Ogg examines the role of pension policies in preventing exclusion of older people and analyses the main mechanisms of pension system reform that may help facilitate this. In Chap. 30, Grigoryeva et al. consider the case of the post-Soviet space, and the ways in which differential reforms may impact the capacity of social policies to protect older people from risks of exclusion. Andersen et al., in Chap. 31, explore the potential for innovative micro-level policy and practice to prevent social exclusion of nursing home residents from local life. In Chap. 32, Leppiman et al. focus on digital service policy in Finland and Estonia as a mediator of broader sets of exclusions and inclusions in older-age. Finally in Chap. 33, Kucharczyk analyses the potential of the European Pillar of Social Rights to address social exclusion of older people in Europe, and the measures necessary to ensure this comes about.

Section IX presents the book’s conclusion chapter. The chapter seeks to draw together various threads from the preceding sections, and their contributions, and chart future directions for research and policy development on social exclusion in later life.

7 Concluding Remarks

This book aims to advance research and policy debates on social exclusion of older people. In both established and emerging ageing societies, the exclusion of older adults is harmful to individuals and the effectiveness and solidarity of communities and nations. Regardless of the future patterns of the COVID-19 outbreak, it appears that the pandemic, as with many other major crises, has exposed longstanding mechanisms of exclusion and entrenched, multiple forms of disadvantage for heterogenous older populations. It has also exposed the importance of factors like institutional structures, and their underlying values, in how they constitute policy responses to age-related risk and ultimately influence the relative nature of exclusion and real and perceived differences across contexts. The COVID-19 pandemic has as such only served to enhance the relevance and timeliness of this volume. In pursuing its four objectives, this book targets contributions that together will provide a critical analysis of current state-of-the-art knowledge, and the basis for the development of a forward-looking research agenda. It is hoped that through these contributions that this book will inspire a commitment to scholarship and evidence-informed action on social exclusion in later life.

References

Adams, V., Kaufman, S. R., Van Hattum, T., & Moody, S. (2011). Aging disaster: Mortality, vulnerability, and long-term recovery among Katrina survivors. Medical Anthropology, 30, 247–270.

AGE Platform Europe. (2020). COVID-19 and human rights concerns for older persons. https://www.age-platform.eu/sites/default/files/COVID-19_%26_human_rights_concerns_for_older_persons-April20.pdf

Atkinson, A. B. (1998). Social exclusion, poverty and unemployment (CASE paper).

Ayalon, L., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2017). Taking a closer look at ageism: Self- and other-directed ageist attitudes and discrimination. European Journal of Ageing, 14, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0409-9.

Barnes, M., Blom, A., Cox, K., & Lessof, C. (2006). The social exclusion of older people: Evidence from the first wave of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA): Final report. London: Office for the Deputy of Prime Minister.

Biggs, S., & Kimberley, H. (2013). Adult ageing and social policy: New risks to identity. Social Policy and Society, 12(2), 287–297. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746412000656.

Börsch-Supan, A., Kneip, T., Litwin, H., Myck, M., & Weber, G. (eds.) (2015). Ageing in Europe: Supporting policies for an inclusive society. Berlin: De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-043704-1. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110444414

Bradshaw, J. (2004). How has the notion of social exclusion developed in the European discourse? Economic and Labour Relations Review, 14(2), 168–186.

Brooke, J., & Jackson, D. (2020). Older people and COVID-19: Isolation, risk and ageism. Journal of Clinical Nursing. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15274.

Dahlberg, L., McKee, K. J., Fritzell, J., Heap, J., & Lennartsson, C. (2020). Trends and gender associations in social exclusion in older adults in Sweden over two decades. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 89, 104032.

Dahlberg, L., & McKee, K. J. (2018). Social exclusion and well-being among older adults in rural and urban areas. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 79, 176–184.

Dannefer, D. (2003). Cumulative advantage/disadvantage and the life course: Cross-fertilizing age and social science theory. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58, 327–337.

European Commission. (2011). The European platform against poverty and social exclusion: A European framework for social and territorial cohesion. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online at: http://ec.europa.eu/social/main.jsp?catId=738&langId=en&pubId=6028&type=2&furtherPubs=yes.

Eurostat. (2019). Archive: People at risk of poverty or social exclusion. Eurostat Statistics Explained.

Feng, W. (2012). Social exclusion of the elderly in China: One potential challenge resulting from the rapid population ageing. In C. Martinez-Fernandez, N. Kubo, A. Noya, & T. Weyman (Eds.), Demographic change and local development: Shrinkage, regeneration and social dynamics. Paris: OECD.

Feng, Z., Phillips, D. R., & Jones, K. (2018). A geographical multivariable multilevel analysis of social exclusion among older people in China: Evidence from the China Longitudinal Aging Social Survey ageing study. Geographical Journal, 184, 413–428.

Grenier, A., Hatzifilalithis, S., Laliberte-Rudman, D., Kobayashi, K., Marier, P., & Phillipson, C. (2020). Precarity and aging: A scoping review. The Gerontologist, gnz135. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnz135.

Guberman, N., & Lavoie, J. P. (2004). Equipe vies: Framework on social exclusion. In Centre de recherche et d’expertise de gérontologie sociale. Montréal: CAU/CSSS Cavendish.

Hagan Hennessy, C., Means, R., & Burholt, V. (2014). Countryside connections in later life: Setting the scene. In C. Hagan Hennessy, R. Means, & V. Burholt (Eds.), Countryside connections: Older people, community and place in rural Britain (pp. 95–124). Bristol: Policy Press.

Hargittai, E., Piper, A. M., & Morris, M. R. (2019). From internet access to internet skills: Digital inequality among older adults. Universal Access in the Information Society, 18, 881–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0617-5.

Jehoel-Gijsbers, G., & Vrooman, C. (2008). Social exclusion of the elderly: A comparative study of EU member states. Brussels: CEPS.

Kendig, H., & Nazroo, J. (2016). Life course influences on inequalities in later life: Comparative perspectives. Journal of Population Ageing, 9, 1–7.

Keogh, S., O’Neill, S., & Walsh, K. (2021). Composite measures for assessing multidimensional social exclusion in later life: Conceptual and methodological challenges. Social Indicators Research. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02617-7

Kneale, D. (2012). Is social exclusion still important for older people? The International Longevity Centre-UK (ILC-UK). Available at: https://ilcuk.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Social-exclusion-Report.pdf.

Le Couteur, D., Anderson, R., & Newman, A. (2020). COVID-19 through the lens of gerontology. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, glaa077. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glaa077.

Lenoir, R. (1974). Les exclus: Un français sur dix [The excluded: One French Person out of Ten]. Paris: Seuil.

Levitas, R., Pantazis, C., Fahmy, E., et al. (2007). The multi-dimensional analysis of social exclusion. London: Cabinet Office.

Macleod, C., Ross, A., Sacker, A., Netuveli, G., & Windle, G. (2019). Re-thinking social exclusion in later life: A case for a new framework for measurement. Ageing and Society, 39(1), 74–111. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X17000794.

Mathieson, J., Popay, J., Enoch, E., Escorel, S., Hernandez, M., Johnston, H., & Rispel, L. (2008). Social exclusion meaning, measurement and experience and links to health inequalities. A review of literature. WHO Social Exclusion Knowledge Network Background Paper 1. https://www.who.int/social_determinants/media/sekn_meaning_measurement_experience_2008.pdf.pdf.

Nazroo, J. (2017). Class and health inequality in later life: Patterns, mechanisms and implications for policy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14, 1533. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14121533.

North, M. S., & Fiske, S. T. (2013). Subtyping ageism: Policy issues in succession and consumption. Social Issues and Policy Review, 7, 36–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2012.01042.x.

Phillipson, C. (2020). Austerity and precarity: Individual and collective agency in later life. In A. Grenier, C. Phillipson, & R. Settersten (Eds.), Precarity and ageing: Understanding insecurity and risk in later life (Ageing in a global context) (pp. 215–235). Chicago: Policy Press.

Prattley, J., Buffel, T., Marshall, A., & Nazroo, J. (2020). Area effects on the level and development of social exclusion in later life. Social Science & Medicine, 246, 112722.

ROSEnet. (2020). Multidimensional Social Exclusion in Later life: Briefing Paper and a Roadmap for Future Collaborations in Research and Policy. In: K. Walsh and T. Scharf (series Eds.), ROSEnet Briefing Paper Series: No. 6. CA 15122 Reducing Old-Age Exclusion: Collaborations in Research and Policy. ISBN: 978-1-908358-76-9.

Scharf, T. (2015). Between inclusion and exclusion in later life. In K. Walsh, G. Carney, & A. Ní Léime (Eds.), Ageing through austerity: Critical perspectives from Ireland (pp. 113–130). Bristol: Policy Press.

Scharf, T., & Bartlam, B. (2008). Ageing and social exclusion in rural communities. In N. Keating (Ed.), Rural ageing: A good place to grow old? (pp. 97–108). Bristol: The Policy Press.

Scharf, T., Phillipson, C., & Smith, A. E. (2005). Social exclusion of older people in deprived urban communities of England. European Journal of Ageing, 2, 76–87.

Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2012). Social exclusion in later life: A global challenge. In T. Scharf & N. Keating (Eds.), From exclusion to inclusion in old age: A global challenge (pp. 1–16). Bristol: The Policy Press.

Silver, H. (2019). Social exclusion. In A. Orum (Ed.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of urban and regional studies (pp. 1–6). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118568446.eurs0486.

Townsend, P. (1979). Poverty in the United Kingdom: A survey of household resources and standards of living. Aylesbury: Hazel Watson & Viney Ltd, Great Britain.

United Nations. (2020). A defining moment for informed, Inclusive and targeted response. Issue brief: Older persons and COVID-19. Available at: https://www.un.org/development/desa/ageing/wp-content/uploads/sites/24/2020/04/POLICY-BRIEF-ON-COVID19-AND-OLDER-PERSONS.pdf

Van Regenmortel, S., De Donder, L., Dury, S., Smetcoren, A. S., de Witte, N., & Verté, D. (2016). Social exclusion in later life: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Population Aging, 9, 315–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10262-016-9145-3.

Van Regenmortel, S., De Donder, L., Smetcoren, A., et al. (2018). Accumulation of disadvantages: Prevalence and categories of old-age social exclusion in Belgium. Social Indicators Research, 140, 1173–1194. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1817-8.

Walsh, K., O’Shea, E., & Scharf, T. (2012). Social exclusion and ageing in diverse rural communities: Findings of a cross border study in Ireland and Northern Ireland. Galway: Irish Centre for Social Gerontology.

Walsh, K., O’Shea, E., & Scharf, T. (2019). Rural old-age social exclusion: A conceptual framework on mediators of exclusion across the life course. Ageing & Society, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000606.

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., & Keating, N. (2017). Social exclusion of older persons: A scoping review and conceptual framework. European Journal of Ageing, 14, 81–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0398-8.

Warburton, J., Ng, S. H., & Shardlow, S. M. (2013). Social inclusion in an ageing world: Introduction to the special issue. Ageing & Society, 33, 1–15.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Open Access This chapter is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made.

The images or other third party material in this chapter are included in the chapter's Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the chapter's Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.

Copyright information

© 2021 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (2021). The Intersection of Ageing and Social Exclusion. In: Walsh, K., Scharf, T., Van Regenmortel, S., Wanka, A. (eds) Social Exclusion in Later Life. International Perspectives on Aging, vol 28. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_1

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51406-8_1

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-51405-1

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-51406-8

eBook Packages: HistoryHistory (R0)