Abstract

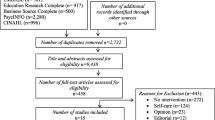

Although the concept of experiential expertise is relatively new in modern health care services, policy, and research, it has profound implications for improving participation in healthcare. The absence of theoretical and conceptual clarity has led to poor understanding and miscommunication among researchers, health practitioners, and policy makers. The aim of this article is to present a concept analysis of experiential expertise and to explain its defining characteristics, applicability, and significance. A combination of Rodger’s evolutionary method combined with Schwartz-Barcott and Kim’s hybrid model was selected as a method for the analysis of the experiential expertise concept. This method combines theoretical (24 definitions) with empirical data analysis (17 interviews). Antecedents, attributes, and consequences are determined. A comprehensive definition is provided, and the interrelatedness between experiential expertise and related concepts was mapped. Experiential expertise is a complex process exceeding the boundaries of individual experiences. Its availability cannot be taken for granted. Using experiential expertise in health care can facilitate patient empowerment leading to improved quality of life and health care. The present study offers clarity by proposing a conceptual model that can assist researchers, policy makers, and health care professionals in facilitating implementations in practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abel, K., and C. Browner. 1998. Selective compliance with biomedical authority and the uses of experiential knowledge. In Pragmatic women and body politics, ed. M. Lock, and P. Kaufert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Batalden, M., et al. 2017. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMC Quality & Safety. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004315.

Blume, S. 2017. In search of experiential knowledge. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 30 (1): 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2016.1210505.

Boevink, W. 2006. Stories of recovery. Working together towards experiential knowledge in mental health care. Utrecht: Trimbos-instituut.

Boevink, W. 2012. HEE: towards recovery, empowerment and experiential expertise of users of psychiatric services. In Empowerment, lifelong learning and recovery in mental health: towards a new paradigm, ed. P. Rian, S. Ramon, and T. Greacen, 36–50. New York: Palgrave.

Boevink, W. 2017. Hee! Over Herstel, Empowerment en Ervaringsdeskundigheid in de psychiatrie. Utrecht: Trimbos Instituut.

Boevink, W., et al. 2016. ‘A user-developed, user run recovery programme for people with severe mental illness: A randomised control trial’. Psychosis 2439: 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17522439.2016.1172335.

Boivin, A. 2014. What are the key ingredients for effective public involvement in health care improvement and policy decisions? A randomized trial process evaluation. The Milbank quarterly 92 (2): 319–350. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12060.

Borkman, T. 1976. Experiential Knowledge: A analysis of self-help groups. Social Service Review 50 (3): 445–456.

Bovenberg, F., G. Wilrycx, and G. Francken. 2011. Inzetten van ervaringsdeskundigheid [The enablement of expertise by experience]. Sociale Psychiatrie 29: 21–28.

Burda, M.H.F., et al. 2012. Harvesting experiential expertise to support safe driving for people with diabetes mellitus: A qualitative study evaluated by peers in a survey. Patient 5 (4): 251–264. https://doi.org/10.2165/11631620-000000000-00000.

Burda, M.H.F., et al. 2016. Collecting and validating experiential expertise is doable but poses methodological challenges. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 72: 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2015.10.021.

Caron-Flinterman, J.F., J.E.W. Broerse, and J.F.G. Bunders. 2005. ‘The experiential knowledge of patients: A new resource for biomedical research?’. Social Science & Medicine (1982) 60 (11): 2575–2584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.023.

Casman, M.-T., et al. 2010. Experts by experience in poverty and in social exclusion. Antwerp-Apeldoorn: Garant.

Castro, E.M., T. Van Regenmortel, K. Vanhaecht, W. Sermeus, and A. Van Hecke. 2016. Patient empowerment, patient participation and patient-centeredness in hospital care: A concept analysis based on a literature review. Patient Education and Counseling 99 (12): 1923–1939.

Castro, E.M., et al. 2017. ‘Co-design for implementing patient participation in hospital services: A discussion paper. Patient Education and Counseling. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2018.03.019.

Castro, E.M.Van, T. Regenmortel, C. Van Wanseele, W. Sermeus, and K. Vanhaecht. 2018. Participation and healthcare: a survey investigating current and desired levels of collaboration between patient organizations and hospitals. Journal of Social Intervention: Theory and Practice 27 (4): 4–28.

Civan, A., et al. 2009. ‘Locating patient expertise in everyday life’. GROUP ACM SIGCHI Int Conf Support Group Work., pp. 291–300. https://doi.org/10.3816/clm.2009.n.003.novel.

Crawford, M.J., et al. 2002. ‘Systematic review of involving patients in the planning and development of health care. BMJ Clinical Research 325: 1263.

Currana, T., R. Sayers, and B. Percy-Smith. 2015. Leadership as experts by experience in professional education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 186: 624–629.

de Jonge, M. 1994. Beroep cliëntdeskundige. Een nieuwe ster aan het firmament van de gezondheidszorg. Medisch Contact 49: 1627–1628.

Deegan, P. 1993. Recovering our sense of value after being labelled mentally ill. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing 31 (4): 7–11.

Dreyfus, S., and H. Dreyfus. 1980. A five-stage model of the mental activitities involved in directed skill acquisition. Berkeley.

Erp, N. D. Van Boertien, S. Van Rooijen. 2015. ‘Basiscurriculum Ervaringsdeskundigheid. Bouwstenen voor onderwijs en opleidingen voor ervaringsdeskundigen [Basic Curriculum experiential expertise Foundation for education and training for experience experts].’, p. 146. http://www.kenniscentrumphrenos.nl/wp-content/uploads/2015/04/AF1373-basiscurriculum-ervaringsdeskundigheid_web.pdf.

Frampton, P. et al. 2008. Patient-centered care improvement guide. Derby. http://planetree.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Patient-Centered-Care-Improvement-Guide-10.10.08.pdf. Accessed 22 Nov 2015.

Gielen, P., J. Godemont, K. Matthijs, and A. Vandermeulen. 2010. Zelfhulpgroepen. Samenwerken aan welzijn en gezondheid. Leuven: Lannoo Campus.

Goertz, Gary. 2006. Social science concepts: A user’s guide. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Greenhalgh, T. 2005. Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ 331 (7524): 1064–1065. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68.

Karbouniaris, S, and E. Brettschneider, E. 2008. Inzet en waarde van ervaringsdeskundigheid in de GGZ [Enablement and value of expertise by experience in mental health care]. Utrecht.

Knooren, J. 2010. Training psychiatric clients to become experts by experience. European Journal of Social Education 16: 201–208.

Korevaar, L., and J. Droës. 2011. Handboek rehabilitatie voor zorg en welzijn Handbook rehabilitation for care and well-being]. Bussum: Coutinho.

Lam, A. 2000. ‘Tacit knowledge, organizational learning and societal institutions: An integrated framework. Organization Studies 21 (3): 487–513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840600213001.

Malfait, S., K. Eeckloo, and A. Van Hecke. 2017. The influence of nurses’ demographics on patient participation in hospitals: A cross-sectional study. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing 14 (6): 455–462.

Mclaughlin, H. 2009. ‘What’ s in a name : “Client”, “patient”, “customer”, “consumer”, “expert by experience”, “service user”—what’ s next ? The British Journal of Social Work 39 (6): 1101–11147.

Miaskiewicz, T., and K.A. Kozar. 2011. Personas and user-centered design: how can personas benefit product design processes. Design Studies 32: 417–430.

Mockford, C., et al. 2012. ‘The impact of patient and public involvement on UK NHS health care: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care : Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care/ISQua 24 (1): 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzr066.

Nickel, S., A. Trojan, and C. Kofahl. 2016. Involving self-help groups in health-care institutions: the patients’ contribution to and their view of “self-help friendliness” as an approach to implement quality criteria of sustainable co-operation. Health Expectations. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.12455.

Plooy, A. 2007. Ervaringsdeskundigen in de hulpverlening—bruggenbouwers of bondgenoten! [Experience Experts in counseling—bridge builders or allies!]. Tijdschrift voor Rehabilitatie 16 (2): 14–21.

Polit, D., and C. Beck. 2012. Nursing Research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, vol. 9. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott/Williams & Wilkins Health.

Posthouwer, M., and H. Timmer. 2013. Een ervaring rijker [A new experience]. Amsterdam: SWP.

Repper, J., and T. Carter. 2011. A review of the literature on peer support in mental health services. Journal of Mental Health 20 (4): 392–411. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2011.583947.

Rietbergen, C., E. Mentink, and L. Verkuyl. 1998. Inzet van ervaringsdeskundigheid bij de (re)integratie van arbeidsgehandicapten [Deployment of experiential expertise in the (re) integration of disabled people]. Utrecht.

Rodgers, B., and K. Knafl. 2000. Concept development in nursing: foundations, technqiues, and applications. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Roets, G., et al. 2012. Pawns or pioneers? the logic of user participation in anti-poverty policy-making in public policy units in belgium. Social Policy and Administration 46 (7): 807–822. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9515.2012.00847.x.

Ruis, J., D. Polhuis, and I. de Hoop. 2012. Ervaring is de beste leermeester. De meerwaarde en positie van ervaringsdeskundigen. Vakblad Sociale Psychiatrie 31: 43–46.

Schwartz-Barcott, D., and S. Kim. 2000. An expansion and elaboration of the hybrid model of concept development. In Concept development in nursing: foundations, techniques, and applications, ed. B.L. Rodgers, and K.A. Knafl. Philadelphia: Saunders.

Scourfield, P. 2010. A critical reflection on the involvement of “experts by experience” in inspections. British Journal of Social Work 40 (6): 1890–1907. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp119.

Sharma, A.E., et al. 2017. ‘The impact of patient advisors on healthcare outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research 17 (1): 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2630-4.

Solbjør, M., and A. Steinsbekk. 2011. User involvement in hospital wards: Professionals negotiating user knowledge. A qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling 85 (2): 144–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2011.02.009.

Spiesschaert, F., D. Trimbos, and M. Vangertruyden. 2009. De methodiek Ervaringsdeskundige in Armoede en Sociale Uitsluiting. Kennis uit het werkveld. Berchem: De Link vzw.

Tambuyzer, E., G. Pieters, and C. Van Audenhove. 2014. Patient involvement in mental health care: One size does not fit all. Health Expectations 17 (1): 138–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00743.x.

Thompson, J., et al. 2012. Credibility and the “professionalized” lay expert: Reflections on the dilemmas and opportunities of public involvement in health research. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health Illness and Medicine 16 (6): 602–618. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459312441008.

Timmer, H., and A. Plooy. 2009. Weten over leven, ervaringskennis van mensen met langdurende psychische aandoeningen [Knowing about life, experience knowledge of people with long-term psychiatric disorders]. Amsterdam: SWP.

Tritter, J.Q. 2009. ‘Revolution or evolution: the challenges of conceptualizing patient and public involvement in a consumerist world. Health Expectations : An International Journal of Public Participation in Health Care and Health Policy 12 (3): 275–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00564.x.

Utschakowski, J. (2017) Foundations and consequences of experiential knowledge.

Vandenbempt, K., and B. Demeyer. 2003. Beroepsprofiel. Ervaringsdeskundige in de armoede en sociale uitsluiting. Leuven: Garant Publishers.

van Bakel, M. et al. 2013. Ervaringsdeskundigheid Beroepscompentieprofiel [Experiential Expertise Competency Profile]. Utrecht/Amersfoort. www.ggznederland.nl.

van Erp, N., M. van Wezep, A. Meijer, H. Henkens, and S. van Rooijen. 2011. Werk en opleiding voor ervaringsdeskundigen: Transitie-experiment Eindhoven. Utrecht: Trimbosinstituut.

Van Erp, N., et al. (no date) Werk en opleiding voor ervaringsdeskundigen [Work and training for experience experts]. Eindhoven.

van Haaster, H., and Y. Koster-Dreese. 2005. Ervaren en weten [Experience and Knowledge]. Utrecht: Jan Van Arkel.

van Haaster, H. et al. 2013. Kaderdocument ervaringsdeskundigheid [Framework Experiential expertise]. Utrecht.

Van Regenmortel, T. 2009. Koningin Fabiolafonds voor de Geestelijke Gezondheid, pp. 1–8.

Van Regenmortel, T. 2011. Ervaringsdeskundigheid in de geestelijke gezondheidszorg met betrekking tot werk. [Experiential expertise in mental health related to work]. Welzijnsgids (Gezondheidszorg, Geestelijke gezondheidszorg) 29: 1–22.

Verbrugge, C.J.J.M., and P.J.C.M. Embregts. 2013. Een opleiding ervaringsdeskundigheid voor mensen met een verstandelijke beperking [Training experiential expertise for people with intellectual disabilities]. Tilburg.

World Health Organisation. 2015. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services. Geneva: World Health Organisation. http://www.who.int/servicedeliverysafety/areas/people-centred-care/global-strategy/en/.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Author | Definition |

|---|---|

Health care | |

Borkman (1976) | Experiential knowledge is truth learned from personal experience with a phenomenon rather than truth acquired by discursive reasoning, observation, or reflection on information provided by others. The two most important elements of experiential knowledge are (1) the type of information on which it is based and (2) one’s attitude towards that information. * The type of information is wisdom and know-how gained from personal participation in a phenomenon instead of isolated, unorganized bits of facts and feelings upon which a person had not reflected. This wisdom and know-how tend to be concrete, specific, and commonsensical, since they are based on the individual’s actual experience, which is unique, limited, and more or less representative of the experience of others who have the same problem. *The second element is the certitude that what one experiences indeed becomes knowledge. Experiential knowledge is the ‘‘truth learned from personal experience with a phenomenon’’ and experiential expertise refers to ‘‘competence or skill in handling or resolving a problem through the use of one’s own experience’’ |

Foundation for learning disabilities | A term used by the recovery movement to draw attention to the value of working alongside service users. A particular approach which acknowledges a person’s capacity to work towards their own rehabilitation |

Care Quality Commission (2016) http://www.cqc.org.uk/content/become-an-expert-experience | Experts by Experience are people who have personal experience of using or caring for someone who uses health, mental health, and/or social care services that we regulate |

Commission for Social Care Inspection (2009) in Scourfield (2010) | People who have chosen to become more closely involved with the organization, developing their skills, knowledge, and expertise (CSCI 2009) An expert by experience is a person who, because of their shared experience of using services, and/or ways of communication, visits a service with an inspector to help them get a picture of what it is like to live in or use the service. Experts by experience do not need to have experienced an identical service. What matters is that they know what it is like to need a service |

Carer Quality Commission (2009) in Scourfield (2010) | Experts by experience are people who are using services now or have done so in the past, people who need services but have not been offered them, people who need services but have not been offered any that are appropriate, people living with or caring for a person who uses services |

Burda et al. (2016) | Having the experience of living with a chronic disease implies having experiential knowledge. When this experiential knowledge of patients is joined and shared, a communal body of knowledge—called experiential expertise—can arise Experiential expertise relates to the disorder as a physical–biological and psychosocial entity and relates to social roles in various life domains, such as family, school/work, social networks, public places, and health care services. An essential aspect of experiential expertise is its transmissibility to peers and others and aimed at the benefit of peers. Experiential expertise contributes to the improvement of ways to deal with and solve restrictions resulting from the disorder and the medical regimen, with the emphasis on consequences for daily life. An important aim of transferring experiential expertise is to help people with a chronic disease increase their social integration and societal participation and hence achieve the quality of life they aspire to |

Burda et al. (2016) | Patient-specific knowledge is often implicit and concerns the lived experiences of individual patients regarding their bodies and their illnesses as well as cure and care. The first step towards experiential expertise is made when these experiences are converted into personal insights that enable a patient to cope with their individual illness and disability. When experiences are tested and shared by peers, the communal body of knowledge exceeds the boundaries of individual experiences and starts being ‘experiential expertise,’ which can be transferred to peers. Experiential expertise can be regarded as an intersubjective body of competence in terms of attitude, knowledge, and skills, tested and adapted continuously in daily life by the experiential experts themselves |

Popay and Williams (1996) in Thompson et al. (2012) | The implicit, direct knowledge, experience, and understanding that an individual has about their body, health, and illness or about health services, care, and treatment |

Gielen et al. (2010) | Expertise by experience starts, as the word suggests, from a personal, specific experience related to a problem. At a later stage, that problem is converted to a personal interpretation of the problem. In other words, experiential knowledge is specific and tangible. It is about the tacit and embodied knowledge of an individual. Expertise by experience also has another dimension: it involves the ability to tackle and resolve a problem. By this, Expertise by experience transcends the individual experience. It is more about abstracted knowledge that can be enabled to help others. Expertise by experience is embedded knowledge on a collective level. It is a gradual quality—one can have less or more Expertise by experience—and it is dynamic. Expertise by experience can indeed change over time. It is transferred in self-help groups from peer to peer. Gradually, it also starts to gain ground in regular care, where it is enabled externally. [Own translation] |

Currana et al. (2015) | We use the term ‘expert by experience’ to refer to roles beyond the immediate experience of being a service user or carer when that expertise is deployed in other situations, for example, for contributing to student recruitment, teaching, research, policy consultation, or service improvement |

de Jonge (1994) | The development of expertise by experience is a process. Combining individual experiences does not necessarily generate experience-based knowledge Experience-based knowledge only arises when analyzing those experiences and when theories based on experiences from the field are generated. Expertise by experience is established through a process where individual experiences are combined and where theories based on experiences that lean on shared experiences are formulated |

Deegan (1993) | One can speak of expertise by experience when a patient recovered sufficiently and when he is able to cope with his problems. It also means that the patient can see his illness in a wider context. He has knowledge about his condition and knows which factors contribute to recovery. He also has a view on his condition and the therapies he has followed. With this knowledge, he is able to help others on their way to recovery |

Mental health care | |

Geestelijke gezondheidszorg Eindhoven en de Kempen (2011) | Expertise by experience is a source of knowledge that is founded upon experience, upon the process of recovery and the exchange of your own personal story with the stories of others. The struggle with several complaints, psychological illness, opposition, and uncertainties about choices made are all part of this. In addition, resilience, the ability to find creative solutions and adjustments, the support of others, the new identity, and new experiences are a source of expertise by experience. Therefore, expertise by experience is not something that can be learned through education. It is the ability to apply and use all the knowledge gathered from those experiences. [Own translation] |

Boevink (2017) | In order to gain confidence in your own power, and to be able to develop and expand that power, experience-based knowledge is required: knowledge about what improves and what impedes one’s own recovery process. In our view, recovery and empowerment lean on experience-based knowledge and expertise by experience. People who have experienced severe and long-term psychological suffering, all have a unique story. This story encompasses the meaning that people give to their problems and the strategies they develop to cope with these problems. This is the so-called personal experience-based knowledge. Together, all these individual stories form collective experience-based knowledge: knowledge about what it is like to live with psychological vulnerability and its consequences. If someone is capable of transferring this knowledge to others, in any form, we use the term expertise by experience. Expertise by experience is essential for the recovery of people diagnosed with psychological illness. At an individual level, it contributes to the empowerment of peers in their search for their own powers. At a higher level, it clears the way for the influence of clients on the improvement of medical care. [Own translation] |

Karbounianiss and Brettscheider (2009) | Expertise by experience is the result of a processing process and of the reflection about… Recognition and acknowledgement are the leading principles. Although knowledge can be meaningful for one’s personal life and the life of peers initially, it should also be verifiable, for instance, by evaluation research Experience-based knowledge is the expertise by experience and knowledge: That is used, and considered useful by experts by experience That is based on the experts by experiences’ own experience That refers to competencies to commit knowledge in favor of a third party (e.g., phrasing emotional experiences) That can be used in several fields and practices But that can be applicable to a specific area and a specific context. [Own translation] |

Koningin Fabiolafonds voor de Geestelijke Gezondheid (2009) | Expertise by experience is the specific expertise that was constructed by learning-from-experiences: by taking your own experiences seriously, by processing them for yourself and reflecting on them and additionally by considering similar experiences of others as being serious, by listening to those experiences and assimilating them in own reflections. [Own translation] |

Korevaar and Droës (2008) | Expertise by experience is good example of how empowerment works. It encompasses the idea of sharing own experiences with peers. Throughout this process one will gradually learn how own experiences can fit in a ‘we-story’ and how this can be applied to other contexts: e.g., improvement of care, policy making, or political action. [Own translation] |

Plooy (2007) | Expertise by experience is a skill, a profession based on specific and mature knowledge. It is embedded in comprehensive literature of experience stories of people with long-term psychological illness. It is knowledge that is supported by scientific research and that leans on the experiences and the development of the client-movement in the 30s. This knowledge refers to the recovery of psychological illness and the support of people with psychological illness. Experiential knowledge is the integration of individual experiences into a commonly shared story. That is expert by experience. When you have the ability to transfer this knowledge in an efficient way, and when you put it at stake for the improvement of the position of psychiatric patients, then you develop something that we could call expertise by experience. [Own translation] |

Posthouwer and Timmer (2013) | Expertise by experience is the professional dedication and transfer of knowledge gathered by analysis of and reflection on one’s own experiences and experiences of peers, completed with knowledge from other sources such as literature, presentations, and media. [Own translation] |

Ruis et al. (2012) | One can speak of expertise by experience when people offer emotional, social, or practical help and engage personal experiences to help people with similar experiences (peers). [Own translation] |

van Erp et al. (2011) | Expertise by experience is the expertise in supporting others to develop your own experiential knowledge and to support the recovery process. At the same time, it is the expertise in the field of more general experience knowledge and the enabling of it in care and in the emancipation and the battle against stigmatization. [Own translation] |

Social Work (poverty) | |

Casman et al. (2010) | This experience is: Assimilated: the capacity of experts by experience to carry out their missions effectively requires, initially, that they have assimilated the experiences acquired all along their own life path spent in poverty Supplemented by specific training: during the first three years of their engagement, these experts by experience follow a part-time training course, which is intended to prepare them to take up their activities within the federal public services Connected to wider horizons acquired by the exchange and the expertise of others’ experiences: these three years of training are an opportunity for the experts by experience of similar mind to be in contact with each other on a regular basis and to exchange thoughts on their respective paths. Moreover, the training process aims at maximizing the dynamics of exchange and expression Gradually enriched by professional experience: finally, expertise acquired through real-life experiences continues to be refined and to become enriched by doing the professional work itself |

Spiesschaert et al. (2009) | Trained experts by experience in poverty and social exclusion are persons who have experienced poverty since birth. They have processed and expanded their experience to broader poverty experience, and through training they were handed attitudes, skills, and methods to practice and apply the broadened poverty experience in a well-grounded way in all fields of poverty prevention. [Own translation] |

Spiesschaert (2005) | Trained experts by experience in poverty and social exclusion, persons who have experienced poverty, who have coped with and extended this experience and who, through training, have acquired attitudes, skills, and methods to apply this extended poverty experience professionally in one or several areas of the fight against poverty. In other words, they have received the opportunity through training to start or continue their coping process, to extend their experiences with that of others and to develop attitudes, skills, and methods which are important in the field of practice. However, the official designation of the training, as it is recognized by the department of education, differs from the term used in the poverty decree. The latter refers to expert by experience in poverty, while within the department of education, the training is known as training for “experience expert in poverty and social exclusion” |

Appendix 2

Discipline | Gender | Sector | Country | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Respondent 1 | Expert by experience | f | Medical health | Belgium |

Respondent 2 | Expert by experience | f | Medical health | Belgium |

Respondent 3 | Expert by experience | f | Medical health | Belgium |

Respondent 4 | Expert by experience | m | Medical health | Belgium |

Respondent 5 | Professional | f | Medical health | Belgium |

Respondent 6 | Expert by experience | m | Medical health | Netherlands |

Respondent 7 | Expert by experience | m | Medical health | Netherlands |

Respondent 8 | Expert by experience | m | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 7 | Expert by experience | m | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 9 | Expert by experience | f | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 10 | Expert by experience | f | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 11 | Professional | m | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 12 | Professional | f | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 13 | Researcher | m | Mental health | Belgium |

Respondent 14 | Researcher | m | Mental health | Netherlands |

Respondent 15 | Expert by experience | m | Social work | Belgium |

Respondent 16 | Professional and researcher | m | Social work | Belgium |

Respondent 17 | Professional | m | Social work | Belgium |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Castro, E.M., Van Regenmortel, T., Sermeus, W. et al. Patients’ experiential knowledge and expertise in health care: A hybrid concept analysis. Soc Theory Health 17, 307–330 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-018-0081-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-018-0081-6