Abstract

The aim of this paper is to understand the conditions under which an international soft-law agreement may result in widespread compliance across different countries. In particular, it will be assessed whether the number and size of the actors involved in the bargaining process may be able to explain the contents of the accord and, consequently, the level of regulatory isomorphism it is able to create. A game theory coordination model is suggested as a theoretical answer to this question, whereas the two Basel Accord cases are used to test the model empirically. The Basel example has a twofold interest. On the one hand, the Basel I agreement is widely cited as a primary example of successful soft-law international agreement because of its worldwide implementation. On the other hand, the recent approval of the Basel II Accord and the unenthusiastic way it has been received in many countries makes it possible to contrast it with the Basel I experience. The appreciation of the circumstances that led to the two Accords may be suggestive of the reasons behind the widespread adoption of the Basel I Accord as opposed to the piecemeal implementation of Basel II.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

As the FSF website confirms: ‘through promoting sound policy making and orderly and efficient markets, the voluntaryadoption of standards of good practice will (…) help to make the international financial system stronger and more stable’, www.fsforum.org accessed 2 July 2006.

Giovanoli, M. (2002) Reflections on international financial standards as ‘soft law’. Essays in International Financial and Economic Law, The London Institute of International Banking, Finance and Development Law Ltd., no. 37, p. 6. The same view may apply to domestic soft law.

Giovanoli (2002: 7), reference 2 above.

Abbott, K. W. and Snidal, D. (2000) Hard and soft law in international governance. International Organization 54 (3): 421–456.

Cf. Alford, D. E. (2005) Core principles for effective banking supervision: An enforceable international financial standard? Boston College International and Comparative Law Review 28: 237. For a clear analysis of advantages and disadvantages of soft law, see Abbott and Snidal (2000), reference 4.

Ho, D. E. (2002) Compliance and international soft law, why do countries implement the Basle Accord? Journal of International Economic Law 5 (3): 649.

In the neorealists’ view ‘all international law is soft’, Abbott and Snidal (2000: 422), reference 4.

This is consistent with the arguments of the ‘managerial’ school. See for instance Chayes, A. and Chayes, A. H. (2001) On compliance. chapter in L.L. Martin and B.A. Simmons. International Institutions, Boston: MIT Press, pp. 247–249.

See Downs, G. W. et al (1996) Is the good new about compliance good news about cooperation? International Organization 50 (3): 379–406.

Simmons, B. A. (2000) International law and state behaviour: Commitment and compliance in international monetary affairs. The American Political Science Review 94 (4): 819–835.

Drezner, D. W. (2004) Who rules? The regulation of globalisation. November (mimeo).

See Jervis, R. (1978) Cooperation under the security dilemma. World Politics 30 (1): 167–214 and Jervis, R. (1988) Realism, game theory and cooperation. World Politics, 40(3): 317–349. Contra, Snidal, D. (1985) Coordination vs. prisoner dilemma: implications for international cooperation and regimes. The American Political Science Review 79(4): 923–942.

Lee, L. L. C. (1998) The Basle Accords as soft law: Strengthening international banking supervision. Virginia Journal of International Law 39: parts 1–4.

Abbott, K. W. (1989) Modern international relations theory, a prospectus for international lawyers. Yale Journal of International Law 14: 346–350.

See for instance Slaughter, A. M. et al (1998) International law and international relations theory: A new generation of interdisciplinary scholarship. American Journal of International Law 932: 367–393 and the entire issue of International Organization (Summer 2000).

Guzman, A. T. (2001) International Law: A Compliance-based Theory. UC Berkeley School of Law, W.P. 47, April: 1, and cf. Chayes, A. and Chayes, A.H. (1993) On compliance. International Organization 47(2): 175–205.

Within political science, the neorealist scholarship, differently from the institutionalists, argues that institutions have no real effect too, so that both soft and hard international laws are indeed ‘soft’ and thus only constitute ‘window dressing’. ‘This perspective is so deeply held among the neorealists that they rarely discuss international law at all’ (Abbott and Snidal, 2000: 422). Cf. supra note 7.

As in Guzman (2001), the enforcement school is here acknowledged as a legal strand of literature rather than a political science theory, see note 16.

Downs et al (1996), see note 9.

Ibid.

Abbot and Snidal (2000), p. 427, see note 4.

Cf. Simmons, B. A. (2001) The international politics of harmonization. International Organization 55: 589–620, who explains harmonisation as a result of hegemonic power; Vogel (Vogel, D. (1995) Trading up, Cambridge: CUP) who hypothesize a global ‘California Effect’; Mattli, W. (2001) The politics and economics of international institutional standards setting: An introduction. Journal of European Public Policy 8: 328–344, and Koremenos, B. et al (2001) The rational design of international institutions. International Organization 55(4): 761–799.

Drezner, D. W. (2005) Globalization, harmonization and competition: The different pathways to policy convergence. Journal of European Public Policy 12 (5): 841–859.

See Slaughter, A. M. (1995) International law in a world of liberal States. European Journal of International Law 6: 503–538, and Singer, D.A. (2004) Capital rules, the domestic politics of international regulatory harmonization. International Organization 58: 531–565, who tries to go beyond both the traditional functional argument as that of Kapstein, E.B. (1989) Resolving the regulator's dilemma: International coordination of banking regulations. International Organization 43(2): 323–347, and Kapstein, E.B. (1992) Between power and purpose: Central bankers and the policy of regulatory convergence. International Organization 46(1): 265–287, but also innovate the ‘Chicagoan’ idea of ‘redistributive cooperation’ as in Oatley, T. and Nabors, R. (1998) Redistributive cooperation: Market failure, wealth transfers, and the Basle Accord. International Organization 52(1): 35–54. The idea that domestic policy determines international relations is also in Putnam, R. (1988) Diplomacy and domestic policy, the logic of two-level games. International Organization 42(3): 427–460, who proposes a two-level game to understand the results of international negotiations.

Guzman (2001: 17), see note 16.

See for instance Jervis (1988) and (1978), see note 12; Snidal, D. (1982) The game theory of international politics. World Politics 38 (4): 25–57.

Cf. Jervis (1988), see note 12.

O’Neill, B. (1989) Game Theory and the Study of Deterrence of War. In: P.C. Stern et al (ed.) Perspectives on Deterrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jervis (1998), see note 12.

This definition of coordination games is provided by Snidal (1985), see note 12.

On this theory see at least Keohane, P. (1984) After Hegemony, Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

The assumption that an hegemonic actor exists (see Simmons, 2001, note 22), is challenged by Braithwaite and Drahos who observe that ‘these days no one really leads the globalisation of banking regulation (…) the hegemony of the United States in international monetary relations has no counterpart in banking regulation’ ( Braithwaite, J. and Drahos, P. (2000) Global Business Regulation. Cambridge: CUP).

Kindleberger, C. (1976) Systems of International Economic Organization. In: D. Calleo (ed.) Money and the Coming World Order. New York: NY University Press.

The public good problem may be seen as a special case of Prisoner Dilemma.

Most of these assumptions are common to Drezner (2004), see note 11.

Simmons (2000), see note 10.

Drezner (2004), see note 11.

Ibid.

Although coercion is costly to enforce, great powers rarely bear this cost directly. More often, they take advantage of IFIs like the IMF or the WB.

I thank an anonymous referee for reminding me to emphasise that the model described in the following is not supposed to provide the reader with a complete and exhaustive answer to the research question. By simplifying the decisions’ structure of the actors, the model only aims to achieve a clearer and more precise understanding of some main drivers behind each player's strategies and to draw some positive conclusions regarding the most likely outcomes of the negotiation process. For this reason, the formal calculations in the following should not be regarded as a substitute but simply as a tool for analysis.

Helpman, E. (2004) The Mysteries of Economic Growth. Cambridge: Belkknap Press, pp. 71–72.

Drezner, D. W. (1999) The Sanctions Paradox. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Following the Basel Concordat of 1983, branch supervision is primary responsibility of the home supervisor but this rule does not accommodate the case referred to in the text.

Cf. Drezner (2004), see note 11.

This evidence is clearly anecdotic though, being the level of development just an (imprecise) proxy for market size. The same caveat should be applied to the regulatory stringency analysis that follows.

Although Financial Services Foreign Direct Investments (FSFDI) would clearly be a better proxy, as argued by the Committee on the Global Financial System (CGFS, 2004, Foreign direct investments in the financial sector of emerging market economies, BIS, March, p. 7), ‘data on FSFDI flows that are comprehensive and methodologically consistent across countries are not available’.

Although for simplicity this model assumes that international coordination is costly for small states because they need to comply with more stringent standards, other economic effects should be acknowledged. For example, lower barriers to global capital markets have been proved to increase the volatility of economic output.

Barth, J. R. et al. (2001) The Regulation and Supervision of Banks around the World: A New Database. Policy Research Working Paper 2588, Washington: World Bank.

Pape, R. (1997) Why economic sanctions do not work. International Security 22: 90.

Gruber, L. (2000) Ruling the World: Power Politics and the Rise of Supranational Institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

The only difference with the previous assumptions is that here d may assume different values depending on the country. C represents the degree of coercion (that is market sanctions) that may be imposed by A on B.

George, A. (1979) Case Studies and Theory Development: The Method of Structured, Focused Comparison. In: P.G. Lauren (ed.) Diplomacy: New Approaches in History, Theory, and Policy. New York: The Free Press.

In particular, the main problem is the inconsistency of data among different countries.

The BIS is the Bank of International Settlements, established in Basel after the First World War to manage Germany's war repayments. For further information see http://www.bis.org/about/history.htm.

Braithwaite and Drahos (2000), see note 32.

BIS. (2001) History of the Basel Committee and its membership. March http://www.bis.org/bcbs/history.pdf, accessed 10 July 2008.

Breithwaite and Drahos (2000), see note 32.

Notably, the BCBS's first achievement was the drafting of a number of principles (the ‘Concordat’) based on the idea that ‘no foreign banking establishment should escape (adequate) supervision’ (BIS, 2001: 2, see note 55).

The numerator was divided into a (at least) 50 per cent Tier 1 and a 50 per cent Tier 2. The denominator was composed by assets and off-balance sheet items, both adjusted by risk. For further details see Lastra, R. M. (2004) Risk-based capital requirements and their impact upon the banking industry: Basel II and CAD III. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 12 (3): 225–239.

Braithwaite and Drahos (2000: 117), see note 32.

Ibid.

BIS (2001: 3), see note 55.

Basel Committee interview, 1998, as cited by Braithwaite and Drahos (2000: 117), see note 32.

Ibid.

Gruber (2000).

Braithwaite and Drahos (2000: 118), see note 32.

Ibid.

Ibid.

For the relative evidence see section ‘Explaining variation’.

Sebenius, J. K. (1992) Negotiation analysis: A characterization and a review. Management Science 38 (1), pp. 18–38, 345.

Gowan, P. (1999) The Global Gamble. London: Verso, p. 26.

Further details are in Kapstein, E. B. (1994) Governing the Global Economy, International Finance and the State. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

The first one is the simplest and draws on what was required by the BI Accord. The second one is the foundation internal risk-based (IRB) approach that mainly relies on the banks’ capability to calculate their required capital on the basis of their assessment of the counterparty's default risk. Finally, the third ‘advanced’ IRB (A-IRB) approach allows the bank to use its own models to forecast not only the probability of default (PD) of the counterparty, but also the loss given default (LGD), the exposure at default (EAD) and the remaining maturity (M). Under Pillar I, three different approaches of increased sophistication (BIA, SAOR and AMA) are also used for the calculation of operational risk. See Lastra (2004), note 58. On BII there is a long and miscellaneous literature. See for example, for a technical discussion: Danielsson, J. et al (2001) An academic response to Basle II. Financial Markets Group, LSE, Special Paper 130, Decamps, J.P. et al (2002), The three pillars of Basel II: Optimizing the mix in a continuous time model. GREMAQ, Toulouse; for a legal discussion Llewellyn, D.T. (2001) A regulatory regime and the new Basel Capital Accord. Journal of Financial Regulation and Compliance 9(4): 327–337; Thomas, H. and Wang, Z. (2005) Interpreting the internal ratings-based capital requirements in Basel II. Journal of Banking Regulation 6(3): 274–289; Lastra (2004), note 58.

For an empirical demonstration see the five Quantitative Impact Studies (QIS) gradually published by the BIS. They are available on www.bis.org.

On this literature see Coglianese, C. and Lazer, D. (2003) Management based regulation: Prescribing private management to achieve public goals. Law & Society Review 37: 691–730.

That is small and medium enterprises.

Shin, H. S. (2005) Financial Risk Analysis, Course-pack. London: London School of Economics and Political Science.

As defined in the ISD (Investment Services Directive, 93/6/EEC).

These are all those banks with consolidated total foreign exposure above $10 billion and consolidated total assets of more than $250 billion. According to Cornford, A. ((2006a) The global implementation of Basel II: Prospects and outstanding problems. Policy Issues in International Trade and Commodity Study Series. Geneva: UNCTAD), they currently account for 99 per cent of the foreign assets and two-thirds of all the assets of US banks. Despite other (‘opt-in’) banks may adopt Basel II if they meet the eligibility criteria for the AMA and A-IRB approaches, US regulators believe that most of them have no need to implement the complex technicalities required by Basel II.

See Howke, J. D. (2003) Retreat from Basel II. Financial Regulator 8 (1); Courtis, N. (2003), Basel split. Financial Regulator 8(1). After a long period in which the results of QIS4 were carefully analysed, the US regulators have finally decided to adopt BII (Kroszner, R.S. (2007) Implementing Basel II in the US, Speech at the S&P Conference 2007, New York, New York http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/kroszner20071113a.htm, accessed 15 June 2008).

See note 68.

See Attachment 1 of Risk-based Capital Standards: Advanced Capital Adequacy Framework – Basel II. http://www.federalreserve.gov/generalinfo/basel2/FinalRule_BaselII/, accessed 23 March 2007.

This might particularly be the case of the Congress, the OTS, the OCC and the FDIC. As the chair of FDIC, Sheila Bair, confirmed in a 2007 interview, ‘the advanced approaches could result in a dangerous fall in the level of capital kept by banks to absorb shock losses’ (Global Risk Regulator, July – August 2007).

Courtis (2003: 52), see note 79.

Rym Ayadi is one of the few observers who clearly recognises this risk ( Ayadi, R. (2008) Basel II Implementation in the midst of Turbulence. CEPS Task Force Report, June 2008, p. 107).

This was anticipated by Luo Ping, officer of the CBRC, during the Second Annual Conference on the Future of Financial Regulation, FMG, LSE, London, April 6–7, 2006. Ping added that a detailed policy paper will be probably issued in the next months on the CBRC website.

Ping reported that China currently has four main commercial banks, which together hold 58.3 per cent of total deposits.

Cfr. The Financial Regulator, China sets Basel II deadline, 12-1, 2007.

Global Risk Regulator, various issues. See also Financial Stability Institute. (2006) Implementation of the New Capital Adequacy Framework in Non-Basel Committee Member Countries. Occasional Paper No. 6, September; Financial Stability Institute (2004) Implementation of the New Capital Adequacy Framework in Non-Basel Committee Member Countries. Occasional Paper no. 4, July; Cornford (2006a, note 78); Cornford, A. (2005) The Global Implementation of Basel II: Prospects and Outstanding Problems. Geneva: Financial Markets Center, June and Cornford A. (2006b) Basel 2 at Mid-2006: Prospects for Implementation and Other Recent Developments. Geneva: Financial Markets Center, July.

FSI. (2006) Implementation of the New Capital Adequacy Framework in Non-Basic Committe Member Countries. FSI Occasional paper No. 6, BIS, Basel.

The non-BCBS data are to be taken with some caution, because they are probably the result of two different subgroups. On one side, those 16 countries that have joined the EU and are thus subject to the CRD and therefore compliant with most of the Accord; on the other the non-EU non-BCBS countries whose implementation process appears definitely more troublesome.

Cf. Cornford (2006a), see note 78.

US Department of Commerce, as cited by Simmons (2001), see note 22.

World Bank. (2004) data query, www.devdata.worldbank.org/data-query/, accessed 13 August 2006.

OECD. (1992) Bank Profitability 1981–1990. Paris.

Ibid.

OECD. (2004) Bank Profitability 1994–2003. Paris.

US Census Bureau. (2006) Economic Fact Sheet http://factfinder.census.gov/servlet/ accessed 15 August 2006.

OECD (2004), see note 96. In the same year, for instance, French banks accounted only for 2300 billion euro.

According to Simmons (2001, note 22), this dominance is clearly facilitated by the role of the dollar, which is still used for nearly 86 per cent of world foreign exchange transactions; see BIS (2007) Triennial Central Bank Survey, Foreign exchange and derivatives market activity in 2007, December.

No sufficient data available for the Netherlands and Japan.

Investment banks and securities houses are included in the sample. A complete time series from 1988 is not available.

Data for other areas are not complete but, similarly to Asia, tend to prove the US's dominance in international trade.

This is the only ‘developing macro-region’ for which OECD data on foreign direct investments are sufficiently complete during the analysed period.

This period has been chosen in consideration of the Basel Capital Accord case study which is performed in the following. As it will be described, the Basel I Accord was agreed in 1988 whereas the Basel II Accord (that is the so-called revised framework) was reached in 2004.

See supra, § 3.b.

Ibid.

Simmons (2001: 595), see note 22.

Ibid.

As explained in the model above the only costless equilibrium is the status quo.

The CPWG is comprised of ‘representatives from CPLG organisations that are not members of the Committee’. See http://www.bis.org/bcbs/index.htm#Core_Principle_Liaison_Group accessed August 2006.

Ibid.

Nouy, D. (1999) Strengthening the Banking System: Issues and Exposures, in Strengthening the Banking System in China: Issues and Experience. BIS Policy Paper no. 9, October.

Ibid.

BIS (2000: 4), Report for the G7 Okinawa Summit, Basel, November.

For a discussion on the literature on fairness, see Carraro et al (2006).

Courtis (2003: 46), see note 79.

Courtis (2003), see note 79.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Apart from the EU, the most relevant case of full implementation is Australia, whose decision is probably because of its political-economical affinity with the United Kingdom.

that is International Governmental Organisation. Drezner (2004), see note 11.

Drezner (2004), see note 11. For Drezner (2004: 23) the important point is that ‘relative to club IGOs, the international financial institutions pose a more divergent set of actor preferences and greater transaction costs of decision-making’.

Koremenos et al (2001), see note 22.

Davies, H. (2003) Is the global regulatory system fit for purpose in the 21st century? Monetary Authority of Singapore Lecture, 20 May, p. 6; IMF (2001), Quarterly report on the assessment of standards and codes, Policy Development and Review Department, June.

Acknowledgements

The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not involve the responsibility of CONSOB. I gratefully acknowledge the help of Rosa M. Lastra, Giampiero M. Gallo, Julia Black and Mark Thatcher. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix A

Theoretical Demonstration of Hypotheses 1, 2 and Corollary 3

Hypothesis 1:

-

If π i >d i and d i =d for all i with d=f(a−b), this game may be solved as a symmetrical coordination game with three Nash equilibria. Two equilibria are pure strategies: (A retains and B switches) or (B retains and A switches). The third equilibrium is a mixed strategy equilibrium that may be calculated in a stochastic environment where p=Prob(A retains). A chooses a probability p such that B is indifferent between retaining and switching to A's standards. Analogously q=Prob(B retains) is chosen such that A is indifferent to its strategy set. Thus

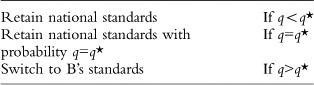

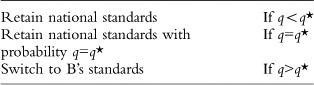

The optimal reaction of A to B's strategy is R a (q). Three different equilibria are then possible:

B's optimal reaction to A's standards is R b (p). Similarly, three equilibria are possible:

Assuming that both actors have a uniform distribution of beliefs over p and q, the likelihood of coordination at A's standards in equilibrium is

The result of this equality is that L increases with π b and decreases with π a . Recalling that for all i, π i is a linear transformation of y j /(y i +y j ), it is easy to observe that when y a increases, π a decreases and π b increases. If π a decreases and π b increases, the value of L increases as well. Therefore, Ceteris paribus, when the market size of state A (that is y a ) increases, so does the likelihood of coordination at A's preferred standards.

Hypothesis 2:

-

Recalling that when y a increases, π a monotonically decreases and π b monotonically increases, the demonstration of the second proposition is straightforward. As d is between 0 and 1, there exists a y* such that for all y a >y*, π a −d<0. When this inequality is verified, A's dominant strategy is to retain standards. B will respond to this strategy by switching its standards if π b −d>0. As π b increases with y a , by Brouwer's fixed point theorem there must be a y** such that, Ceteris paribus, both the inequalities are verified for all y a >y**. Given these values of y, the only equilibrium is coordination at A's standards.

The previous considerations are not easily extended to the case of n actors. Still, a hypothetical scenario with one leader and n−1 followers may be helpful in understanding what kind of outcome may result from an increase in n. Accordingly, let us assume that y b is the sum of the market shares of all the countries different from A, that is, (y b +y c +y d + ⋯). π a may then be viewed as a linear transformation of

It is easy to observe that, Ceteris paribus, for n → ∞, π a tends to 1. Thus, the likelihood L of a coordinated equilibrium at A's standards decreases and y* increases. In practice, other things equal, an increased number of actors in a coordination game makes it more difficult to reach an agreement at A's preferred standards. Alternatively, a decreasing relative market size makes it harder for a leading country to force other states to coordinate at its own standards. Thus, the following corollary:

Corollary 1:

-

Ceteris paribus, for n → ∞ the likelihood L of a coordinated equilibrium at A's standards decreases.

See Figures A1, A2, A3 and A4

Appendix B

Developing Countries FDI Inward And Outward Stock And Flow (Study Construction Using UNCTAD Data)

Appendix C

Asia’S FDI Inward And Outward Positions From 1988 To 2004 (Study Construction Using OECD Data)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Novembre, V. The bargaining process as a variable to explain implementation choices of international soft-law agreements: The Basel case study. J Bank Regul 10, 128–152 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1057/jbr.2008.23

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/jbr.2008.23