Abstract

Purpose

Improvements in D′ (the fatigability constant for running) subsequent to training interventions remain elusive. High-intensity interval training (HIIT) within the severe intensity domain for short durations (< 2-min) have been theorized to improve D′. The purpose of the present study was to assess this in a group of moderately trained individuals.

Methods

Eighteen participants completed graded exercise testing (GXT), 40-m sprint testing and a 3-min all-out test (3MT) for running to determine key mechanistic and physiological parameters. Participants were randomly assigned into one of two groups based on intensity prescription (G140% = 140% of critical speed [CS]), or time intervals (G90-s = 90-s) to complete a twice-weekly training intervention for 6-weeks followed by re-assessment.

Results

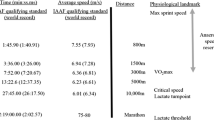

No between-group differences were present either prior to or following the intervention. Substantial and meaningful improvements were detected during the post-intervention period for both groups for VO2max (G140%: + 7.60%; G90-s: + 11.67%), speed evoking VO2max (sVO2max; G140%: + 4.33%; G90-s: + 2.92%), gas exchange threshold (GET; G140%: + 12.02%; G90-s: + 20.52%), speed evoking GET (sGET; G140%: + 4.17%; G90-s: + 7.92%), CS (G140%: M = 0.62 m/s; G90-s: M = 0.46 m/s), D′ (G140%: M = − 56.34 m; G90-s: M = − 18.36 m), FI% (G140% M = − 6.75%; G90-s: M = − 4.38%) and maximal distance (G140%: M = 49.67 m; G90-s: M = 58.38 m).

Conclusions

The prescribed intensities and durations were insufficient to elicit improvements in D′. Improvements in D′ may be dependent on very short-duration intervals (i.e. < 60 to 90-s) at speeds exceeding 140% CS but below maximal sprint speed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 10th ed. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2018.

Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting threshold by gas exchange anaerobic. J Appl Physiol. 1986;60(6):2020–7.

Bergstrom HC, Housh TJ, Cochrane-Snyman KC, Jenkins NDM, Byrd MT, Switalia JR, Schmidt RJ, Johnson GO. A model for identifying intensity zones above critical velocity. J Strength Cond Res. 2017;31(12):3260–5.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: part I: cardiopulmonary emphasis. Sport Med. 2013;43(5):313–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0029-x.

Buchheit M, Laursen PB. High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle: part II: anaerobic energy, neuromuscular load and practical applications. Sport Med. 2013;43(10):927–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0066-5.

Christensen LB, Johnson RB, Turner LA. Research methods, design and analysis. 12th ed. Harlow: Pearson Education Limited; 2015.

Clark IE, West BM, Reynolds SK, Murray SR, Pettitt RW. Applying the critical velocity model for an off-season interval training program. J Strength Cond Res. 2013;27(12):3335–41.

Courtright SP, Williams JL, Clark IE, Pettitt RW, Dicks ND. Monitoring interval-training responses for swimming using the 3-min all-out exercise test. Int J Exerc Sci. 2016;9(5):545–53.

Craig JC, Vanhatalo A, Burnley M, Jones AM, Poole DC. Critical power: possibly the most important fatigue threshold in exercise physiology. London: Elsevier Inc.; 2019.

Cumming G, Calin-Jageman R. Introduction to the new statistics: estimation, open science, and beyond. Taylor and Francis, New York: Routledge; 2017.

Ferretti G. Energetics of muscular exercise. London: Springer International Publishing; 2015.

Fukuba Y, Whipp BJ. A metabolic limit on the ability to make up for lost time in endurance events. J Appl Physiol. 1999;87(2):853–61.

Gastin PB. Energy system interaction and relative contribution during maximal exercise. Sport Med. 2001;31(10):725–41. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-200131100-00003.

Jamnick NA, By S, Pettitt CD, Pettitt RW. Comparison of the YMCA and a custom submaximal exercise test for determining VO2max. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2016;48(2):254–9. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000763.

Jones AM, Burnley M, Black MI, Poole DC, Vanhatalo A. The maximal metabolic steady state: redefining the ‘gold standard’. Physiol Rep. 2019;7(10):1–16. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.14098.

Jones AM, Doust JH. A 1% treadmill grade most accurately reflects the energetic cost of outdoor running. J Sports Sci. 1996;14(4):321–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640419608727717.

Jones AM, Vanhatalo A. The ‘critical power’ concept: applications to sports performance with a focus on intermittent high-intensity exercise. Sport Med. 2017;47(s1):65–78. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0688-0.

Jones AM, Wilkerson DP, Dimenna F, Fulford J, Poole DC. Muscle metabolic responses to exercise above and below the “ critical power ” assessed using 31 P-MRS. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(2):585–93. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00731.2007.

Kirkeberg JM, Dalleck LC, Kamphoff CS, Pettitt RW. Validity of 3 protocols for verifying VO2max. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32(4):266–70. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1269914.

Kordi M, Menzies C, Parker L. Relationship between power—duration parameters and mechanical and anthropometric properties of the thigh in elite cyclists. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2018;118(3):637–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00421-018-3807-1.

Kramer M, Clark IE, Jamnick N, Strom C, Pettitt RW. Normative data for critical speed and D′ for high-level male rugby players. J Strength Cond Res. 2018;32(3):783–9.

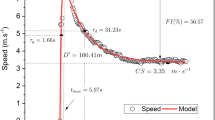

Kramer M, Du Randt R, Watson M, Pettitt RW. Bi-exponential modeling derives novel parameters for the critical speed concept. Physiol Rep. 2019;7(4):e13993. https://doi.org/10.14814/phy2.13993.

Kramer M, Watson M, Du Randt R, Pettitt RW. Critical speed as a measure of aerobic fitness for male rugby union players. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2019;8:518–24.

Miura A, Kino F, Kajitani S, Sato H, Sato H, Fukuba Y. The effect of oral creatine supplementation on the curvature constant parameter of the power-duration curve for cycle ergometry in humans. Jpn J Physiol. 1999;49(2):169–74.

Muniz-Pumares D, Karsten B, Triska C, Glaister M. Methodological approaches and related challenges associated with the determination of critical power and curvature constant. J Strength Cond Res. 2019;32(2):584–96.

Nakahara H, Ueda SY, Miyamoto T. Low-frequency severe-intensity interval training improves cardiorespiratory functions. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2015;47(4):789–798. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000477.

Pettitt RW, Jamnick N, Clark IE. 3-min all-out exercise test for running. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33(6):426–31.

Pettitt RW, Placek AM, Clark IE, Jamnick NA, Murray SR. Sensitivity of prescribing high-intensity, interval training using the critical power concept. Int J Exerc Sci. 2015;8(3):202–22.

Poole D, Burnley M, Rossiter HB, Jones AM. Critical power: an important fatigue threshold in exercise physiology. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2016;48(11):2320–34. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000939.

Poole DC, Jones AM. Oxygen uptake kinetics. Compr Physiol. 2012;2(2):933–96. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c100072.

Rossiter HB. Exercise: kinetic considerations for gas exchange. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(1):203–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c090010.

Samozino P, Rabita G, Dorel S, Slawinski J, Peyrot N, De VES, Morin JB. A simple method for measuring power, force, velocity properties, and mechanical effectiveness in sprint running. Scand J Med Sci Sport. 2016;26(6):648–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/sms.12490.

Scharhag-Rosenberger F, Meyer T, Gäßler N, Faude O, Kindermann W. Exercise at given percentages of VO2max: heterogeneous metabolic responses between individuals. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(1):74–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2008.12.626.

Seiler S, Tønnessen E. Intervals, thresholds, and long slow distance: the role of intensity and duration in endurance training. Sportscience. 2009;13(13):32–533.

Sundberg CW, Fitts RH. Bioenergetic basis of skeletal muscle fatigue. Curr Opin Psychol. 2019;10:118–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cophys.2019.05.004.

Vanhatalo A, Jones AM. Influence of creatine supplementation on the parameters of the “all-out critical power test”. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2009;7(1):9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1728-869X(09)60002-2.

Vanhatalo A, Jones AM, Burnley M. Application of critical power in sport. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2011;6(1):128–36.

Winter DA. Biomechanics and motor control of human movement. 4th ed. Waterloo: Wiley; 2009.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MK conceived the study, performed the data analysis, and drafted and revised the manuscript. EJT completed data collection, contributed to data analysis and interpretation as well as drafting and revising the manuscript. RWP contributed to data interpretation and helped to draft and revise the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree with the order of the presentation of the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Thomas, E.J., Pettitt, R.W. & Kramer, M. High-Intensity Interval Training Prescribed Within the Secondary Severe-Intensity Domain Improves Critical Speed But Not Finite Distance Capacity. J. of SCI. IN SPORT AND EXERCISE 2, 154–166 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-020-00053-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s42978-020-00053-6